The Lost Chapter of a Restless Soul

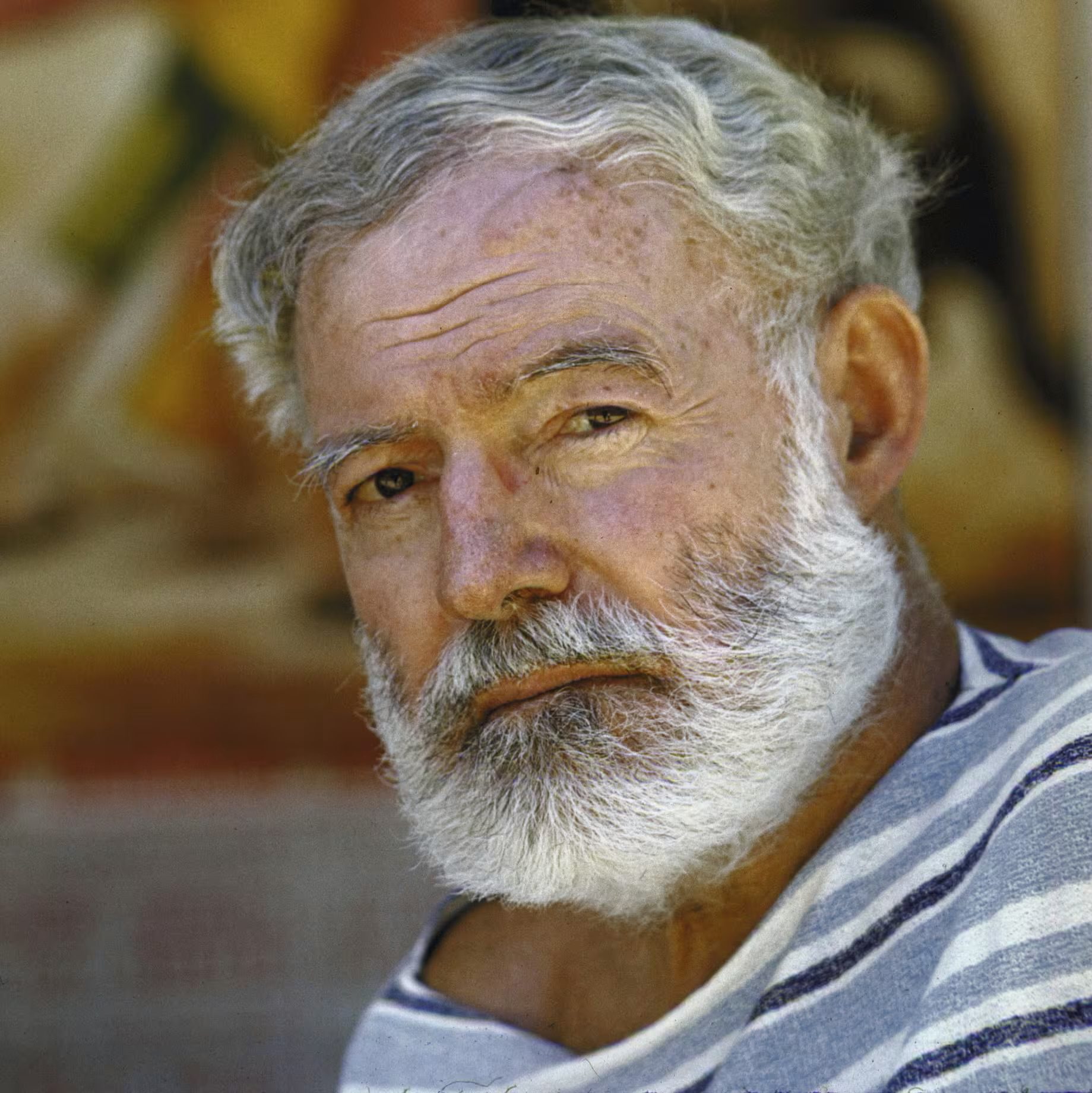

What if Ernest Hemingway had wandered into Ladakh, his boots crunching against the ancient trails of the Himalayas?

The wind would have howled through the valleys, tugging at the edges of his weathered jacket as he took a long, deliberate sip from his flask.

The air, thin but alive with silence, would have suited him. Hemingway was a man who sought the raw edges of the world—Spain, Cuba, Africa.

Would Ladakh have been his final frontier?

This is the Hemingway of the lost chapter, a speculative journey into a world he never wrote about but perhaps should have.

There is something in Ladakh’s stark, unrelenting landscape that echoes the Hemingway code—the hard, clean lines of existence, the silent battles of men against nature, and the unspoken poetry of survival.

A Man Drawn to the Edge

Hemingway was never a man for soft places. His literature, like his life, was carved from the unforgiving.

The Serengeti, the bullrings of Pamplona, the battlefields of Spain—these were not places of comfort, but of confrontation.

It is easy to imagine him in Ladakh, standing at the edge of a monastery perched on a cliff, looking down at the Indus River slicing through the valley below.

The high-altitude air would have burned in his lungs, but he would have liked that. He would have liked the monks, too—their discipline, their quiet endurance.

He would have understood the kind of man who wakes before dawn, walks for miles without complaint, and finds peace in solitude.

Ladakh is not a place that bends for travelers. It forces them to yield. Hemingway, who loved the test, would have found a kindred spirit in its landscapes.

A Land Hemingway Would Have Written About

The great writers are drawn to places that hold stories in their silence. Ladakh is such a place.

The wind moves like a whisper through the apricot orchards, the prayer flags flutter, and the mountains stand unmoved.

Hemingway’s style—his infamous Iceberg Theory—relies on what is unsaid. Ladakh is a land of unsaid things.

Would he have written about a lost traveler, a man finding meaning in the barren beauty of Nubra Valley?

Would he have sat in a small teahouse in Leh, listening to the stories of old Tibetan traders, turning their words into sharp, cutting prose?

Or perhaps he would have gone further, to Turtuk, a village on the edge of a border Hemingway might have wanted to cross, to see what lay beyond.

A World That Exists Beyond Comfort

Hemingway was not a man of excess, but of necessity. He carried what he needed and discarded the rest.

Ladakh, with its high passes and cold nights, is a land that does the same. It strips a man down to his essentials.

Perhaps that is why he never wrote about it—because he never made it here.

But if he had, if his restless feet had carried him beyond Parisian cafés and Cuban seas, he might have found in Ladakh a final proving ground.

And maybe, just maybe, the lost chapter of his life would have been written in the ink of high-altitude solitude.

Hemingway’s Obsession with the Untouched World

Hemingway was a man who sought the raw, the unpolished, the unspoiled.

His life was spent chasing the world before it changed—before modernity dulled its edges, before convenience softened its hardships.

From the dusty streets of Pamplona to the open savannas of East Africa, he wanted to see things as they were, in their most elemental form.

Had he known of Ladakh, he would have been drawn to it.

A place where the modern world still hesitates at the doorstep, where the silence is vast and unbroken.

A land where men do not just exist, but endure. Hemingway admired endurance.

It was at the heart of his greatest characters—Santiago, struggling against the sea; Robert Jordan, standing alone against the inevitable.

In Ladakh, he would have found that same quiet, uncompromising resilience, written in the lines of a shepherd’s face, in the slow, deliberate gait of a monk walking through a frozen valley.

The Hemingway Code Hero in the Himalayas

Every Hemingway protagonist lived by an unspoken code—a way of facing the world with quiet dignity, with courage in the face of certain defeat.

He called them ‘Code Heroes’—men who knew suffering but never let it define them.

Ladakh is full of such men, though Hemingway never met them.

The shepherd who moves with his flock across high-altitude passes, bracing against the wind and the cold, knowing there will be no reward but survival.

The monk who wakes before dawn, kneels in meditation, and asks for nothing.

The old trader in Leh, whose life has been measured in the weight of salt and the length of caravan trails rather than in wealth.

These are Hemingway’s kind of men. Men of few words.

Men who carry their pain quietly, who do what must be done without waiting for applause.

It is easy to picture him in Ladakh, watching, listening, writing.

And perhaps, at night, drinking whiskey by a fire, the mountains rising black and sharp against the stars.

The Man and the Mountain

Hemingway did not write about mountains often, but he understood them.

They were like men—proud, unyielding, eternal.

In Ladakh, he would have met mountains that did not care who he was.

Stok Kangri, Kang Yatse, Nun Kun—peaks that had seen empires come and go, that had watched men cross their passes for centuries, their struggles brief and insignificant against stone and time.

Perhaps he would have climbed one, as he did in Kilimanjaro.

Or perhaps he would have simply watched, knowing that some things are best left unconquered, that not all battles need to be won.

He understood that the greatest fight was always within.

If Hemingway had come to Ladakh, he would not have softened.

The mountains do not allow it.

He would have found a landscape as uncompromising as his prose, as honest as his characters.

And in that, he would have found something rare—something he spent his whole life chasing.

The Iceberg Theory and Ladakh’s Silence

Ernest Hemingway’s writing was defined by restraint. He wrote in stark, lean sentences, stripping away excess, leaving only what was essential.

This was the foundation of his famous Iceberg Theory—the belief that the weight of a story lies beneath the surface, in what is left unsaid.

Ladakh, too, is an iceberg of a place. What it reveals on the surface—its barren mountains, its isolated monasteries, its wind-swept valleys—is only a fraction of what it holds.

Its history, its struggles, its unspoken wisdom remain buried, known only to those who take the time to look deeper.

It is a land of silence, where meaning is found in stillness, and where survival is never loud or boastful. Hemingway would have understood this. He lived by it.

The Power of What Is Unsaid

Hemingway’s greatest characters never said more than they had to. They lived in the spaces between words, in quiet nods and small gestures.

Santiago, the old fisherman, never says how much he loves the sea, but we know.

Jake Barnes never speaks of his pain, but we feel it.

In Ladakh, silence is not an absence—it is a presence.

Imagine Hemingway sitting in a remote monastery in Lamayuru, watching the prayer wheels spin, listening to the wind howl through the valleys.

Would he have written about the monks who wake before dawn, who chant in deep, steady voices, their prayers dissolving into the cold morning air?

Or would he have let the silence speak for itself, understanding that some things are more powerful when left unwritten?

Ladakh as a Hemingway Landscape

Hemingway’s best landscapes are places of extremes—the African savannas, the Spanish bullrings, the Cuban sea.

They are unforgiving yet beautiful, demanding yet rewarding. Ladakh is no different.

The sky here is impossibly wide, the mountains impossibly tall.

The Indus River cuts through the valleys like a scar, a reminder that time, more than anything else, shapes this land.

Hemingway would have admired the way Ladakh makes no attempt to be comfortable. It simply is.

And those who come must accept it on its terms.

Perhaps he would have found something familiar in the hard-eyed nomads who move with the seasons, their lives reduced to what they can carry.

Perhaps he would have envied them. Hemingway always sought a simpler life, but he was too restless to keep it.

A Clean, Well-Lighted Place in Ladakh

Hemingway often wrote about men searching for refuge—a small bar in Madrid, a café in Paris, a lonely cabin in Michigan.

They were not seeking comfort, but understanding. A place where they could exist without having to explain themselves.

Would he have found such a place in Leh? A small, dimly lit room where travelers sit quietly, warming their hands on cups of butter tea?

Would he have found it in a stone house in Turtuk, watching the last light fade over the Karakoram?

Or would he have found it in himself, finally realizing that peace does not come from a place, but from within?

In the end, Hemingway’s Ladakh would not have been in the words he wrote, but in the ones he left unwritten.

A Farewell to Comfort: Trekking Like Hemingway

Hemingway never sought comfort. He sought the test—the raw confrontation between man and nature, the quiet moments of suffering that define character.

He would have seen trekking in Ladakh not as a luxury, but as a trial, a necessary pilgrimage through one of the last untouched landscapes on earth.

Ladakh, like Hemingway’s prose, strips away excess.

There are no indulgences here, no distractions, no layers between a man and his limits.

A trek through its high-altitude passes is not just about reaching a destination.

It is about enduring. Hemingway understood that well.

Would Hemingway Have Walked the Markha Valley?

One can imagine him in Markha Valley, following the winding path through dry riverbeds, crossing wooden bridges strung over rushing glacial streams.

The wind would whip against his face, the sun relentless, the cold biting at dawn. He would have relished the hardship.

He would have stayed in a small homestay—stone walls, a smoky kitchen, a bed little more than a blanket on the floor.

Sitting with a Ladakhi family, drinking butter tea, he would have admired their quiet strength, their simple way of life.

There would be no need for talk—Hemingway preferred men and women who spoke little and did much.

The Thin Air and the Thick Silence

At 4,800 meters, the air is thin, the silence even thinner.

Here, Hemingway would have felt something familiar—the same clarity he found on the African plains, on the Spanish battlefields.

A place where all things unnecessary fall away, where only survival remains.

He would have enjoyed the pain, the exhaustion of each step, the quiet war between body and will.

Like Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, who fought the marlin not for victory but for the dignity of the fight, Hemingway would have walked these trails knowing that the struggle itself was the reward.

A Speculative Diary Entry: Hemingway in Ladakh

Morning, cold. The mountains are older than time itself. Walked for six hours, breathing dust, feet swollen. A man on horseback passed, said nothing, nodded once. A good sign.

Drank tea in a stone hut with a shepherd, his hands thick from years of work. He did not ask where I was from, only if I was going somewhere.

I told him I wasn’t sure. He nodded again. That, too, was a good sign.

The Kind of Journey That Leaves a Mark

Hemingway once wrote, “It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best.”

But walking—trekking—teaches you something deeper. It teaches you how a land breathes, how it moves, how it changes.

In Ladakh, Hemingway would have found what he always sought: a place that does not bend to you, but forces you to bend to it.

He would have left a different man, if he left at all.

Whiskey, War, and the Last Frontier

Hemingway was drawn to war. Not for the glory—he had no illusions about that—but for the raw, unfiltered reality of it.

He was there in Spain, in the trenches of the Ebro. He watched the bombs fall on Madrid, wrote about the death that came without warning.

He stood on the beaches of Normandy, carrying his typewriter like a soldier’s rifle.

If he had made it to Ladakh, he would have been fascinated not by the battles themselves, but by the men who fought them.

The frozen heights of Siachen, the stark borderlands where India and China stand face to face, the long history of invasions that carved this land—these would have caught his eye.

He would have sat with old soldiers in Leh, listening to stories of the high-altitude wars that few in the world know about.

Perhaps he would have wandered further, to the edges of Kargil, where war is not history but something that still lingers in the air.

The Journalist and the Soldier

Hemingway’s best stories were about men caught in conflict—not just war, but the personal battles that never make the headlines.

He wrote about courage, but not in the way most writers did.

For Hemingway, courage was not about charging into battle; it was about standing your ground when no one was watching.

He would have found that kind of courage in Ladakh. In the soldiers who guard the mountain passes, where the enemy is not just across the border but in the cold, in the altitude, in the thin air that steals breath and strength.

Men who know that most of the world has forgotten them, and yet they stay.

A Night in a Bar in Leh

Every Hemingway story has a bar. A place where men gather not to celebrate, but to escape.

Where whiskey is poured in silence, where the only conversations worth having are the ones that don’t need words.

If Hemingway had come to Leh, he would have found a place like that.

A dimly lit room, a wooden counter, a bottle of something strong.

A bartender who pours without asking questions.

A few travelers, a few locals, all drinking in the quiet understanding that the world is vast, and they are small.

He would have liked the kind of man who drinks alone but is never lonely.

The kind of man who has seen too much, who carries his stories in the lines of his face rather than in his words.

Hemingway would have listened, nodded once, and lifted his glass.

A Place Hemingway Would Have Stayed

Ladakh was never meant to be a stop on a journey—it is the kind of place that keeps you.

It is easy to imagine Hemingway sitting in a guesthouse in Nubra, the mountains rising dark against the sky, a notebook open on the table, a pen hovering over a page.

Perhaps he would have written a book here.

A novel about a man searching for something he cannot name, finding it in the silence of the high passes, losing it again when he realizes it was never meant to be his.

A story without a true beginning or end, just as Ladakh itself is a place that does not conform to the easy arcs of fiction.

Or perhaps he would have done what he did best—lived it, and left the writing to someone else.

The Lost Manuscript: Hemingway’s Unwritten Ladakh Novel

Some stories are never written, but they still exist.

They live in the spaces between what was and what could have been.

Hemingway’s Ladakh novel is one of them—a book that was never penned but might have been, had his restless feet carried him to these mountains.

It is easy to imagine it, the opening line sharp and simple: “The wind had not stopped for three days.”

A man alone in a high-altitude valley, following a trail that leads nowhere in particular.

A woman who does not speak his language, but understands him better than most.

A village on the edge of a forgotten road, where the world outside does not seem to exist.

A story about endurance, about losing things without regret, about finding meaning in places that do not ask to be found.

Would It Have Been His Greatest Work?

Hemingway wrote about war, love, and loss. He wrote about the men who survived and the men who did not.

But if he had written about Ladakh, he might have written something different.

A story not about survival, but about acceptance. Not about victory, but about learning how to exist in a world that does not care whether you do or not.

It might have been his simplest book, and maybe his best.

A novel where nothing happens, and yet everything does.

A man walks, drinks tea, listens to the wind. He does not explain himself, and no one asks him to.

And in that, there is peace.

Hemingway’s Ghost in the Himalayas

Hemingway never came to Ladakh. But if you walk its high passes, if you sit in a silent monastery, if you drink whiskey in a dim-lit room in Leh, you might feel him there.

A shadow against the mountain. A voice in the wind. A story left untold.

Perhaps it is better this way.

Some places are too perfect to be captured in words.

Some stories are too vast to fit between the covers of a book.

And some men, no matter how far they roam, never reach their final chapter.

Maybe Hemingway’s Ladakh was never meant to be written.

Maybe it was only meant to be imagined.

The Final Word

If Hemingway had traveled to Ladakh, would it have changed him? Or would he have simply nodded, taken a long sip of whiskey, and carried on, knowing he had finally found a place that did not need him?

Perhaps we will never know.

And perhaps that is exactly as it should be.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor is a writer and literary traveler who explores the landscapes of the world through the lens of timeless storytelling.

With a style that blends sharp prose with deep introspection, his work often blurs the line between fact and fiction, history and imagination.

When he is not writing, he can be found in quiet corners of the world, listening to the wind, searching for stories left untold.