Introduction: Snow-Covered Secrets

A windblown step into Ladakh is not like arriving anywhere else in the Himalayas. Here, altitude reshapes your breath and time itself stretches, as if the landscape prefers to unfold its stories at a slower rhythm. But beneath the prayer flags and dramatic cliffs lies something else—an untold chapter of royal ambitions, trade intrigues, and shifting powers that ruled long before modern maps were drawn.

My journey began not with a plan, but with a question whispered in the stone corridors of Leh Palace. Who were the kings who built this city in the sky? What became of their kingdoms? The guidebooks offered little—tourists came for the monasteries, the views, the quiet. But the bones of a grander history lay just beneath the snow, almost forgotten.

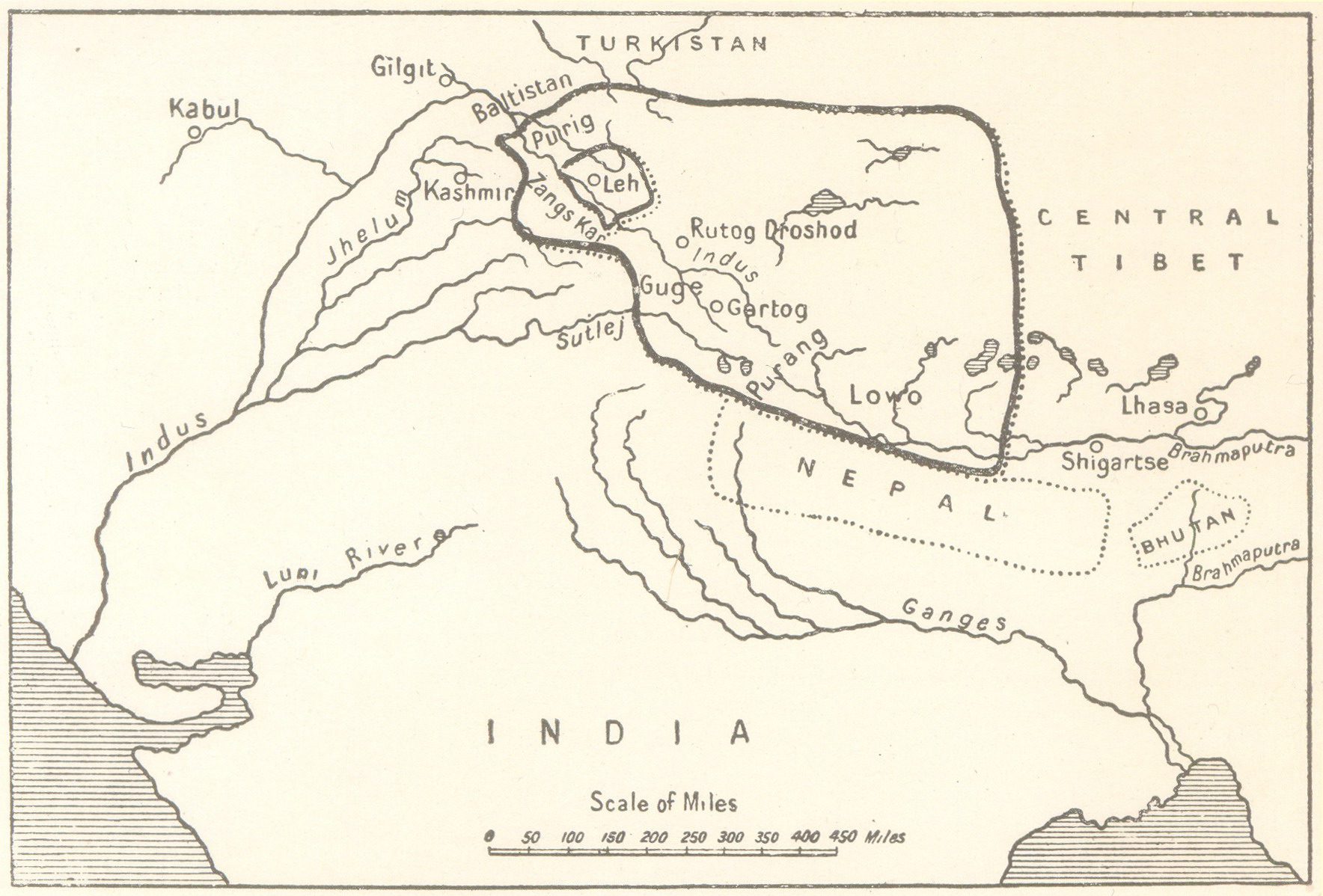

There’s something magnetic about ruins. The silence isn’t peaceful—it’s charged. Every carved doorframe, every toppled stupa holds tension, waiting for someone to notice. As I made my way through sun-bleached villages and fortified remains, I realized Ladakh wasn’t just a remote outpost of India. It was once a center of Himalayan diplomacy, caught between Tibet, Kashmir, Baltistan, and faraway empires.

We often think of lost kingdoms as fiction, the stuff of novels or fantasy films. But Ladakh had its dynasties, its warriors, its exiled queens and spiritual kings. The Namgyal dynasty ruled here with a fusion of politics and Buddhism. Before them, shadowy rulers from Zanskar and even ties to the Guge Kingdom of Tibet formed a rich political tapestry. Their legacies remain, if you know where to look—in murals hidden behind monastery walls, in fortress stones crumbling on lonely hillsides.

Europeans often come to Ladakh seeking solitude, or perhaps spiritual clarity. But I invite you to come for something else: a rediscovery. These snow-covered kingdoms shaped not only the land but the people, the trade routes, and even the monastic traditions that continue today. This journey isn’t just about what’s preserved. It’s about what’s been almost—but not quite—erased.

In this series, I’ll take you beyond the typical travel checklist. We’ll walk through the forgotten fortresses of Zanskar, trace the rise of the Namgyals, and uncover the caravan routes that once pulsed with salt, silk, and secrets. Along the way, you’ll meet Ladakh’s ancient rulers—not through textbooks, but through the footprints they left behind in stone, wind, and memory.

So pack lightly. Bring curiosity. The kingdoms beneath the snow are waiting.

Before the Borders: The Rise of Ladakh’s Kingdoms

We often imagine Ladakh as a land frozen in time, tucked between geopolitical giants like India, China, and Pakistan. But before these modern borders rose like fences across the sky, Ladakh was its own center of power—a kingdom of stone and snow that played a subtle but strategic role in Himalayan politics. It wasn’t isolated; it was connected. And it had rulers who knew how to survive and thrive in this high-altitude theater of ambition.

The earliest written reference to Ladakh as a political entity dates back to the 9th century, when the region was part of a broader Tibetan cultural and political sphere. From these early fragments emerged the Kingdom of Maryul, established by descendants of Tibetan nobility. Maryul wasn’t just a patch of mountain villages—it was a fully functioning kingdom with its capital in Shey, just outside present-day Leh. Its kings styled themselves as heirs of Tibet, even as they carved out their independence.

With time, Maryul gave way to successive dynasties, each building upon the foundation of the last. But it was in the 15th century that Ladakh’s political identity truly crystallized under the rise of the Namgyal dynasty—a line of rulers who would expand the kingdom’s borders, fortify its defenses, and weave Buddhist patronage into the fabric of its authority. They moved the capital to Leh, built the iconic palace that still towers over the bazaar, and invited artists and architects from Kashmir and Tibet to decorate their realm with color and divinity.

Yet Ladakh was never just about kings and conquests. It was a crossroads. Trade caravans from Yarkand, Kashmir, and Baltistan passed through these valleys, carrying salt, turquoise, wool, and silk. With them came travelers, monks, and spies—each with stories, each with allegiances. The Ladakhi kings were skilled not only in battle, but in negotiation. Their rule depended on balancing regional alliances, religious patronage, and environmental resilience.

What fascinates me most is how little of this story is told outside Ladakh. European history buffs pour over the Bourbons and the Habsburgs, yet few have heard of King Sengge Namgyal, the “Lion King,” who built monasteries as easily as he fortified borders. Or King Tashi Namgyal, whose name still echoes in village songs, though no textbook records his diplomacy with Central Asia.

These weren’t mythical figures—they were rulers who lived and died here, whose legacies shaped the monasteries you visit and the roads you drive. And like the mountains themselves, their presence is subtle but unshakable. To know Ladakh is to know its kingdoms—not as distant history, but as the scaffolding of everything you see today.

The Namgyal Dynasty: Warrior Monks and Palace Walls

Perched high above the Leh valley, with walls fading into the same tawny hues as the cliffs they crown, stands the Leh Palace. From afar, it looks abandoned—another ruin in a windswept land. But this was once the seat of a kingdom, and behind its weathered façade lies the heart of the Namgyal dynasty, a royal house as devout as it was daring.

The Namgyals came to power in the 15th century, claiming descent from earlier Tibetan kings. But they were not merely inheritors—they were builders, defenders, and cultural patrons who forged Ladakh’s identity during a time of both great opportunity and growing threat. Their motto, though never carved in stone, might have been this: adapt, or disappear.

Among them, one name dominates the stories locals still tell: King Sengge Namgyal. Known as the “Lion King of Ladakh,” he ruled during the 17th century and left a legacy etched across the mountains. Under his reign, monasteries like Hemis, Hanle, and Chemrey were either founded or greatly expanded. He renovated and fortified Leh Palace, modeled after the Potala Palace in Lhasa—though his was humbler, more pragmatic, suited to the wild Himalayan winds.

But Sengge wasn’t just a monk-builder. He was also a tactician. He led campaigns against invading armies from Baltistan, defended trade routes, and maintained delicate relations with Tibet and Kashmir. His reign is considered the zenith of Ladakhi political power—a time when the kingdom stretched to Zanskar and beyond, and its rulers were respected across the high-altitude world.

Yet power, like snow, never lingers forever. After Sengge’s death, internal strife and external pressures—especially from the expanding Dogra empire and fluctuating relations with Tibet—began to erode Namgyal authority. By the 19th century, the kingdom had been absorbed into Jammu and Kashmir. The royal line faded from political relevance, but not from memory.

Today, the Stok Palace, home to the descendants of the Namgyals, offers a quiet window into what remains. It’s not a museum polished for tourists—it’s lived-in, personal, filled with old thangkas, faded photographs, and the soft creak of time. Visiting feels less like stepping into a museum, and more like being allowed into the final chapter of a book that still lingers on the last page.

I spoke with a young Ladakhi guide at Stok, who said something I’ll never forget: “We still call them kings, even if they don’t rule. Because once someone guards your soul, not just your land, you never forget them.” And perhaps that’s the essence of the Namgyals—not just rulers, but guardians of a cultural flame that still flickers, stubbornly, in the mountain wind.

Zanskar and the Forgotten Fortresses

There’s a moment—usually somewhere after the last paved road disappears into the folds of the mountains—when you realize you’ve entered Zanskar. It feels like the map itself is being rewritten beneath your wheels. What looks like emptiness is in fact layered with centuries of ambition, faith, and survival. Zanskar is a kingdom that history almost forgot, and yet its ruins still grip the ridgelines like clenched fists refusing to fade.

Long before Zanskar became a trekking destination or a footnote in Ladakhi tourism, it was its own realm—often autonomous, sometimes allied, sometimes embattled. Strategically wedged between Ladakh, Himachal, and western Tibet, the region held both political importance and spiritual magnetism. Kings here ruled over scattered valleys with tenacity and humility, building fortresses on hilltops and monasteries in caves, often within the same breath.

One such place is Zangla Fort, a crumbling relic that still watches over the narrow valley with haunting pride. There are no signs, no ticket booths, and often no other travelers. You climb the hillside alone, wind pressing your back like history urging you forward. The walls are broken, the tower hollowed out by time, but the view—oh, the view—is unchanged. From here, Zanskar’s isolation makes sense. This was a fortress not just against armies, but against forgetfulness.

Locals speak of a queen who once ruled from Zangla, exiled from Leh and welcomed by the Zanskari people. Her story is stitched into oral histories, but not the official records. These hills are filled with such whispers—of hidden alliances, monastic scribes doubling as political envoys, and families who fled Dogra incursions by hiding their heirlooms in monastery walls.

Today, travelers pass through Padum or trek over high passes like Phirtse La, but few pause to consider that this remote region once levied taxes, minted decisions, and contributed to the broader political chessboard of the Himalayas. Zanskar was not a backwater. It was a buffer state, a mountain bulwark, and a cultural guardian.

Its architectural remains—forts like Pishu, Sani, and even the ruins near Karsha Monastery—still offer passageways not just through stone but through time. These aren’t tourist sites. They are quiet protests against amnesia.

I met a shepherd near Sani who, when asked if he knew the story of the fort ruins nearby, simply said: “The walls don’t talk anymore, but we still remember what they meant.” His sheep grazed beside broken battlements, as if loyalty to the land had never waned.

Zanskar may not appear in most history books, but walk its ridgelines and you’ll feel the outlines of a kingdom that refused to be erased. In the end, maybe that’s what power is in the Himalayas—not what you conquer, but what you preserve.

Ladakh and the Silk Road: Trade, Power, and Influence

Stand on a rooftop in Leh and close your eyes to the honking cars and café chatter. Imagine instead the crunch of caravan hooves, the jingle of yak bells, and the scent of wool, leather, and fresh-cut turquoise. This was once the soundscape of Ladakh’s Silk Road era, when the town was not just a Buddhist outpost, but a buzzing trade hub that stitched together cultures, commodities, and empires.

Long before colonial borders fragmented the Himalayas, Ladakh sat at the crossroads of the Indo-Tibetan trade corridor, connecting merchants from Central Asia, Tibet, Kashmir, and the Indian plains. What passed through these valleys wasn’t just salt, pashmina, and apricots—it was power. Whoever controlled these mountain passes controlled influence, and the kings of Ladakh knew it.

At the height of the Namgyal dynasty’s rule, especially under Sengge Namgyal, trade was institutionalized. Taxes were levied on caravans. Treaties were signed with Tibetan monasteries to ensure safe passage. Caravanserais were built along the Leh-Kargil-Skardu road, and the kingdom’s fortunes swelled with every yak that crossed into its territory.

What fascinates me is how little remains—not in ruins, but in recognition. The great Salt Route from Rudok to Leh once echoed with barter, gossip, and the clink of coins, yet few modern travelers even know it existed. In places like Nimoo or Saspol, you can still find elderly men who remember stories of their grandfathers’ long winter journeys across the Changthang plateau, returning with bricks of tea from Lhasa and musk pods from Yarkand.

But trade wasn’t just economic—it was cultural. Buddhist texts were copied by hand and transported by monks riding with traders. Islamic influence flowed in from the west, shaping architecture and language in villages closer to Baltistan. The Silk Road made Ladakh plural, layered, and perpetually in negotiation with outside worlds.

Even Ladakh’s geography—those impossible valleys and knife-edged passes—shaped its diplomacy. While it was difficult to invade, it was also difficult to ignore. The Ladakhi court had to remain agile, balancing relations with Tibet, Kashmir, the Mughal Empire, and even British agents probing the frontier by the 19th century.

Today, echoes of that era still shimmer in the bazaars of Leh. Traders from Kargil speak in a blend of Urdu and Ladakhi, stalls sell Chinese thermoses alongside Tibetan incense, and elderly merchants still wear turquoise rings passed down through generations. The trade caravans are gone, but the memory of mobility, of exchange, of Ladakh as a place where worlds met—remains.

To walk the old trade routes of Ladakh isn’t just to follow a historical path. It’s to understand that this frozen desert was once a riverbed of movement, commerce, and cosmopolitan energy. And though the caravans may have vanished into the snow, Ladakh still knows how to connect.

The Guge Kingdom and the Tibetan Connection

In the winding valleys of western Tibet once stood a kingdom both luminous and mysterious: Guge. Known for its cliffside monasteries, golden murals, and philosophical schools, Guge flourished at a time when most of the world had no map for this part of the Himalayas. And while its ruins now lie in the silence of western Tibet’s deserts, its fingerprints are all over Ladakh.

To understand Ladakh’s royal and religious evolution, you must first understand Guge—not as a distant neighbor, but as a teacher, patron, and at times, protector. When Buddhism was reintroduced to Tibet during the 10th and 11th centuries, Guge was the epicenter of the renaissance. Ladakh, then under emerging Tibetan influence, absorbed this energy like parched soil after rain.

It wasn’t just belief that crossed the passes. Artisans, architects, and monastic scholars traveled with texts and brushes, founding monasteries that still stand in Ladakh today. The delicate lines in the frescoes at Alchi Monastery, the iconography in Lamayuru, the layout of Thiksey—all bear the DNA of Guge’s aesthetic and theological sophistication.

Some historians believe that the early rulers of Ladakh, particularly those connected to the Maryul kingdom, were direct descendants of Guge exiles. Whether by blood or by spirit, Ladakh inherited not just structures, but philosophies—blending Tibetan Buddhism with local deities, adapting rituals to the high desert, and fostering a monastic network that would one day rival that of central Tibet.

This relationship wasn’t without complexity. At times, Ladakh asserted its independence; at others, it leaned heavily on Tibetan alliances for political legitimacy and spiritual guidance. During the reign of the Namgyal kings, ties with Lhasa were both symbolic and strategic. The invitation of the famed lama Taktsang Repa to Hemis Monastery is just one example of how Ladakhi rulers intertwined governance with sacred authority, reinforcing their power through faith.

Today, the Tibetan connection still pulses quietly in Ladakh’s spiritual rhythm. You hear it in the chants of novice monks at dawn, see it in the way elderly women turn their prayer wheels along the streets of Leh. Yet what makes Ladakh distinct is not imitation—it is transformation. It took what Guge offered and reshaped it to fit its own mountains, winds, and hearts.

In many ways, Ladakh is Guge’s echo—but not a fading one. It is a reinterpretation. A living remix of a kingdom long gone, but never truly lost. And as the Tibetan plateau becomes increasingly restricted to outsiders, Ladakh remains a window into that shared heritage—a place where the Buddhist traditions of Guge continue to flower beneath the shadow of new empires.

Royal Ruins Today: Where to Feel the Past Beneath Your Feet

If you really want to meet the kings of Ladakh, don’t look for them in books. Look for them beneath your feet. Their legacy is scattered across the valleys—not behind glass, but under open skies, sun-bleached and wind-carved. The ruins of their palaces and forts may not glitter, but they breathe. And when you walk among them, you’re no longer a tourist. You’re a guest in someone else’s story.

Start in Leh Palace. Yes, it’s on every itinerary, but few visitors take the time to pause on each level, to notice the thick earthen walls, the prayer room tucked into a corner, the soot-blackened ceilings that once echoed with courtly decisions. Unlike more curated sites elsewhere in India, this palace feels almost untouched—as if the royal family had just left for tea and might return at any moment.

Then venture beyond Leh. In Shey, the former capital, a modest palace clings to a ridge, its stupa-dotted hills still whispering of the Maryul kings. A short hike leads to meditation caves and ruined fortifications, where time collapses and the past feels close enough to touch.

Drive west and you’ll find Basgo, a redoubt of crumbling towers and mudbrick ramparts that once held back invaders from Kashmir. The ruins are theatrical, rising from ochre cliffs with the kind of drama that no drone shot can truly capture. Step inside the temple and you’ll find a serene Maitreya Buddha watching over the remnants of a vanished court—a divine witness to royal decline.

In the village of Stok, you can meet the present. The Stok Palace is still home to the descendants of the Namgyal dynasty. It’s part residence, part museum, part memoir. You might sip tea with a staff member whose grandfather once served a king, or gaze at royal robes displayed in sunlight rather than spotlights. It’s history without performance—and that’s what makes it unforgettable.

But the most haunting places are the unnamed ones. I once found myself at the ruins of a tiny fort above Tingmosgang, the stones barely held together by moss and memory. No signpost, no entry ticket. Just the hum of wind and a half-buried path. A local farmer told me, “We don’t rebuild it because it still holds us. Like an old tree. You don’t cut it just because it’s not flowering.”

Heritage in Ladakh isn’t something preserved under perfect conditions. It’s something that endures. Cracks, dust, lichen, and all. And that’s precisely what makes these royal ruins so powerful—they invite you to imagine, to reconstruct, to step into a kingdom not as a spectator, but as a participant.

For those willing to go off the guidebook, Ladakh offers more than sites—it offers conversations between stone and soul. So tie your laces. The past is not behind glass here. It’s waiting for you on the trail.

The Kingdoms that Time Forgot: Why This History Matters Today

When we speak of lost kingdoms, we often do so with romantic distance—as if their fall was inevitable, their memory a charming footnote. But in Ladakh, the past hasn’t vanished. It has been folded carefully into the present, like a silk scarf tucked into the lining of a well-worn coat. These dynasties may no longer hold power, but they still shape the way people live, speak, and pray.

Walk through a Ladakhi village and you’ll see it—not in ruins, but in rituals. The layout of homes still mirrors ancient architectural principles. Seasonal festivals trace their origins to royal calendars. Even the titles used for elders echo the structure of vanished courts. This is not nostalgia. This is continuity.

Yet that continuity is under pressure. Rapid modernization, climate change, and mass tourism have begun to wear away at Ladakh’s historical texture. Traditional knowledge is being replaced by generic solutions. Royal stories, once passed down orally during long winters, are fading with each generation that grows up fluent in smartphones but not in local dialects.

That’s why remembering the kingdoms beneath the snow matters—not as an academic exercise, but as a cultural imperative. These were not passive lands forgotten by history. They were active players in trade, diplomacy, and spiritual evolution. Their influence reached beyond their high-altitude valleys, touching Kashmir, Tibet, and Central Asia.

For European travelers, understanding this legacy offers a deeper connection to Ladakh. It transforms the journey from sightseeing to soul-searching. Knowing that the Leh Palace once held political weight, or that the Alchi frescoes are visual relics of a lost Indo-Tibetan world, enriches every step you take. You stop looking for picture-perfect moments and start listening—to the walls, the wind, the people.

Preservation here doesn’t mean restoration in the Western sense. It means protecting the living narrative. Supporting local artisans who still carve in the style of the Namgyal court. Encouraging schools to teach oral histories. Choosing homestays that uphold ancestral traditions, rather than replicating hotel chains.

In a world obsessed with speed and sameness, Ladakh’s forgotten dynasties offer an alternative—a slower rhythm, a rooted identity, a reverence for legacy. Their ruins remind us not just of what was, but of what could be lost if we fail to pay attention.

So let us not call them forgotten. Let us call them waiting. Waiting to be seen, understood, and remembered—not in textbooks, but in footsteps, conversations, and conscious travel. Because the snow may cover the stones, but the stories still burn beneath.

Practical Tips for the Curious Traveler

If the idea of walking through the corridors of vanished kingdoms stirs something in you—something deeper than just ticking off destinations—then Ladakh is ready to receive you. But this is not a place for rush or routine. To explore the royal heritage of Ladakh, you need a different kind of itinerary. One that’s guided by curiosity, patience, and a willingness to listen.

Best Time to Visit:

The ideal months are from late May to early October. Snow has melted, passes are open, and villages come alive with festivals and farming. June and September are particularly good for travelers who prefer quieter roads and crisper air.

Top Sites for History Lovers:

– Leh Palace: Climb each level slowly. Sit on the balcony and watch the city below as the kings once did.

– Stok Palace: A living royal residence—quiet, atmospheric, and still inhabited.

– Basgo Fort: Sculpted into the cliffs, with temples that hold some of the finest mud-plaster murals in Ladakh.

– Shey Palace: The former capital, with massive copper Buddhas and commanding valley views.

– Zangla Fort (Zanskar): For those who want to feel truly remote—no crowds, no signs, just wind and memory.

How to Travel:

Hire a local guide—preferably someone who grew up hearing these stories from their grandparents. They will show you not just where to go, but how to look. Join a Ladakh cultural heritage tour if you want structure, or simply rent a car with a driver and let the roads guide you.

Stay in Homestays:

Wherever possible, choose guesthouses run by Ladakhi families. Not only does this support the local economy, it also gives you access to stories that aren’t printed in any brochure. Ask about the history of the village. Ask who the king was. You’ll be amazed how quickly the past resurfaces.

Be Respectful with Ruins:

Many of these sites are not fenced or guarded, and that’s part of their magic. But treat them as sacred. Don’t climb walls for photos. Don’t pocket pottery shards or touch fading murals. Imagine your own great-grandfather built these stones—how would you want others to behave?

What to Pack:

Good walking shoes, layers for rapidly shifting temperatures, sun protection, and—most importantly—an open notebook. Trust me: you’ll want to write things down. Not facts, but feelings. This is a place that speaks more in sensation than statistics.

Ladakh doesn’t need spectacle to impress. It needs attention. And if you give it yours, the rewards are quietly, profoundly unforgettable.

Closing: A Farewell to Kings

The sun is setting behind the jagged ridge of the Stok Kangri range. Golden light lingers on prayer flags, flutters across barley fields, and brushes the crumbling towers of forgotten forts. Somewhere in the distance, a conch shell sounds from a monastery window. And just like that, the kingdom vanishes once more into the mountains.

But not entirely.

The kings of Ladakh may no longer wear crowns or command armies, but their presence remains—etched into stones, painted on mud-plastered walls, echoed in the way people speak of time and place. Their reigns were not always perfect. They were flawed, ambitious, devout, and deeply human. And that is why their stories still resonate.

I came to Ladakh expecting landscapes. I left with legacies. Not the kind preserved in pristine museums, but the kind you stumble upon when you least expect it—in a grandmother’s story, in the gesture of a monk sweeping a courtyard, in the silence between mountains that once guarded borders and dreams alike.

For those of us who live in places where history is often overwritten or forgotten, Ladakh offers a different perspective. Here, the past is not a burden—it’s a companion. A reminder that identity can be shaped by faith as much as by flags, that survival doesn’t require conquest, and that memory can live in ruins without needing to be rebuilt.

So as you roll up your map and finish your cup of salted tea, I hope you leave a space open—for the things you can’t quite explain, for the questions still unanswered, for the weight of a place that defies being summarized.

And perhaps, as you watch the last light fade over a forgotten palace, you’ll whisper your own farewell to the kings who still watch from the ridgelines, content to be remembered, not as rulers—but as part of the land itself.

About the Author|Elena Marlowe

Elena Marlowe is an Irish-born travel columnist and cultural essayist currently living in a quiet village near Lake Bled, Slovenia. Her writing blends historical depth with lyrical storytelling, often focusing on places where geography and memory intertwine.

With a background in cultural history and a deep love for the lesser-known corners of the world, Elena explores landscapes not only through footsteps but through the lives that have passed before. Her columns are invitations—to reflect, to wander, and to listen to the echoes left behind.

When she’s not traveling or writing, you’ll find her tending a small herb garden, sipping strong tea, or reading 19th-century travelogues by candlelight.