The Silence That Speaks

The wind in Ladakh doesn’t just blow; it sculpts. On mornings like this, high above the Indus valley, the wind shapes silence into something almost physical—etched across the dusty ridgelines, wrapped around the stupas like forgotten prayers. In these high-altitude deserts where the air is thin and the sky is endlessly blue, every step taken is deliberate, every breath a small act of resistance. I wasn’t looking for anything here. And yet, I found something that spoke louder than words: a silence so vast, so full, that it felt more like presence than absence.

We often think of journeys as movement, as progress, as getting somewhere. But Ladakh challenges that notion. There is no hurry here. Time dilates in the altitude. You begin to understand the slowness of mountain logic: erosion over centuries, villages that cling to cliffs with the patience of gods, and people who greet you not with words, but with eyes that seem to have seen too much and yet remain open.

As I hiked alone toward the pass that morning—dust rising with each step, my boots grinding against stone—I couldn’t help but think of Camus. Albert Camus, the French philosopher of the absurd, never hiked in Ladakh. He died too young, too suddenly. But if he had walked these trails, I believe he would have recognized something of himself in this landscape. Not because he was spiritual, or even particularly drawn to nature. But because he understood what it meant to stand in front of something immense and silent, and not turn away.

The wind howled like a question with no answer. There were no signposts, no timelines, no goals. Just the road winding up and up and up—like Sisyphus’s hill. I wasn’t climbing toward enlightenment or peace or personal growth. I was climbing because it was there, and because climbing itself had become its own meaning. “One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” Camus wrote. Here in Ladakh, surrounded by jagged peaks and solitude, I could almost see him smiling—drenched in sweat, lungs burning, quietly pushing the rock uphill, again and again.

This was not Sartre’s world of revolution, of action and engagement. It was Camus’s world—stripped down to its essential questions. Why do we go on? What do we cling to in the face of meaninglessness? How do we respond to the silence of the universe? I didn’t come here with answers. But in that moment, with the wind at my back and the path still rising ahead, I didn’t need them.

I only needed the silence. And the next step.

Camus on the Trail: Absurdism in the Himalayas

To hike in Ladakh is to enter a conversation with something older than language. The mountains do not answer you, but they respond. They respond with silence, with gravity, with the thinness of air that forces your body to slow down and your mind to grow quiet. As I ascended toward the crumbling edges of a nameless ridge near Hemis Shukpachan, I began to feel the strange comfort of that indifference—what Camus once described as the “benign indifference of the universe.”

There is a particular moment on every Himalayan trek when the question arises—not aloud, but somewhere in the lungs, or behind the eyes. Why am I doing this? The cold bites harder, the path disappears into scree, and your breath is no longer yours but something borrowed. The logic of daily life vanishes. This is where absurdism begins to whisper.

Albert Camus didn’t believe in despair. Not really. He believed in confrontation—looking the absurd in the face and refusing to blink. In The Myth of Sisyphus, he imagined a man cursed to push a boulder up a hill for eternity, only for it to roll down again and again. And yet, Camus called this man happy. Not because the task had meaning. But because the man chose to continue anyway.

On that slope in Ladakh, the path no longer mattered. There was no summit, no shrine, no reward. My legs were trembling, my lips cracked from altitude and dry wind, and I felt the familiar ache in my back from hours under a pack. But I was still walking. I had chosen to walk. In that decision—without promise of transcendence, without the illusion of a greater plan—there was a strange kind of freedom.

Camus never preached escape. He resisted hope as much as he resisted despair. He argued that to live is to revolt—not through action alone, but through awareness. In these remote Himalayan valleys, awareness is everywhere. You become aware of every rock, every breath, every shift in light. You become aware of your own fragility. And still, you walk forward.

The absurd hero is not someone who conquers the mountain. He is someone who climbs without reason—and still finds joy in the climbing. In Ladakh, every winding trail feels like a small revolt against gravity, against emptiness, against the need for answers. It is enough to walk. That is the rebellion.

The Landscape as a Mirror

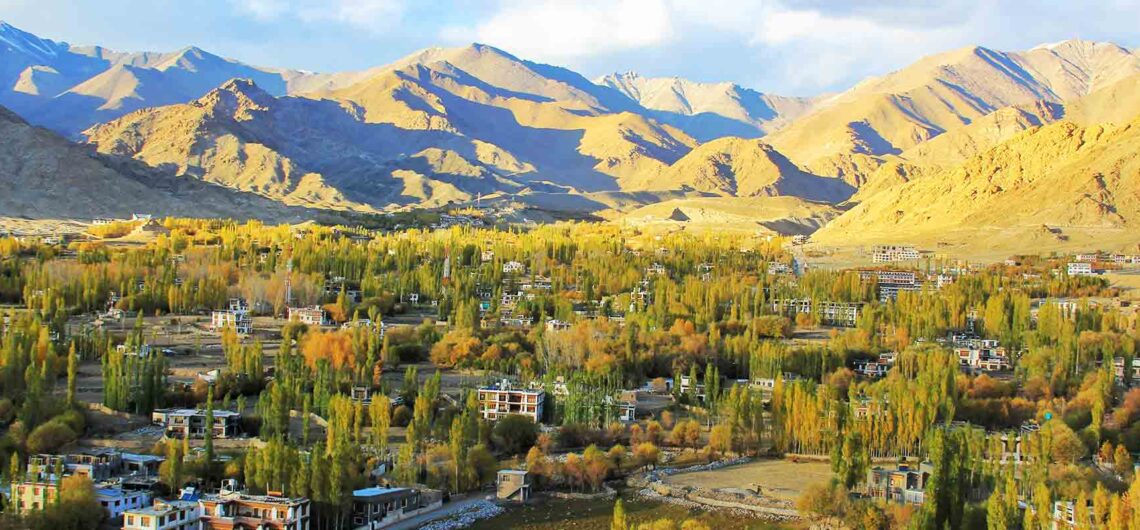

There are places on this earth that feel like mirrors—geographies that don’t just reflect your image but echo your inner condition. Ladakh is one of them. Here, in the high-altitude wilderness north of the Zanskar range, where rivers slice through canyons of rust-colored stone and villages perch like punctuation marks against silence, the landscape doesn’t soothe—it confronts. It offers no soft landings. No green invitations. Only the elemental: rock, wind, dust, sky. It is not beautiful in the conventional sense. It is something deeper. It is honest.

Camus, had he stood here, might have recalled his Algeria—the blinding light, the dryness, the fierce landscapes of his childhood. He called the world absurd not because it was cruel, but because it was indifferent. The mountains of Ladakh are precisely that. They do not care if you reach the summit. They do not adjust for your suffering. They are not spiritual, not even majestic in the way the Alps might be. They simply are. And in that fact lies their strange power.

As I crossed a narrow pass between Yangthang and Ulley, the wind whipped over the ridge like a philosopher’s question left unanswered. Beneath me, a wide valley stretched into haze, dotted with prayer flags fluttering like reminders of how small we are. The air was so dry it stole the moisture from my throat before I could speak. There was no one around for hours. No sound but the shifting of gravel beneath my boots and the call of a kite somewhere above. It felt, in the deepest sense, like walking inside a thought.

This is where nature becomes metaphor. The emptiness of Ladakh reflects the emptiness Camus described—not a void to be feared, but a condition to be accepted. Life, like this trail, is not a road leading somewhere. It simply leads. The sharp edges of the cliffs, the long shadows of evening, the altitude that reminds you of your body’s limits—these are not poetic symbols, but physical truths. Yet, in accepting them, something poetic begins to happen.

I stopped by a small glacial stream—its surface barely moving, the water so clear it seemed invisible—and I thought: perhaps the value of this place is not that it reveals meaning, but that it strips everything else away. Like Camus’s philosophy, Ladakh does not explain. It doesn’t promise anything. It only offers presence. And in that presence, we begin to notice things that usually go unseen: the curve of the ridge, the flight of a single raven, the rhythm of our own heartbeat as we climb.

Ladakh is not a backdrop. It is not a postcard. It is a mirror held to the self. And like the absurd, it demands only one thing from us: awareness. That we see the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. That we continue anyway.

Not a Guide, But a Reflection

This is not a guide to Ladakh. I will not tell you which guesthouses have the best apricot jam, or which homestay has Wi-Fi strong enough to check your email from 12,000 feet. I won’t list trail markers or offer practical advice on acclimatization. Not because these things aren’t useful, but because this journey was never about utility. It was about something more elusive—something closer to mood, to awareness, to philosophical gravity. If you’re reading this in hopes of mapping a route, you’ve already missed the point. The trail doesn’t need a map. It needs your attention.

I came to Ladakh without an agenda. There was no personal transformation to chase, no milestone to achieve. And yet, every step seemed to strip away a layer I didn’t know I was wearing. With each incline, each breathless pause on the side of a scree slope, I found myself becoming smaller—not in defeat, but in relief. The world did not revolve around my problems here. The world did not revolve around anything. It simply turned.

In his writing, Camus reminds us that the human impulse to seek meaning is met by a world that offers none. That is the absurd. And yet, he did not respond with nihilism. He responded with presence. With revolt. With the quiet act of going on, even when the story makes no sense. Hiking in Ladakh is exactly that: a quiet act of going on. A meditation without mantra. A rebellion without noise.

There is a strange freedom in walking without purpose. Not aimlessness, but purposelessness. The difference matters. Purpose implies a goal. Purposelessness implies being. In Ladakh, the destination often disappears behind a pass or vanishes into the blue shimmer of altitude. You learn not to look too far ahead. You learn to look down, at the earth beneath your boots. You learn to listen to your own breath, to count steps when your mind starts racing. You learn to be where you are.

And isn’t that the essence of Camus’s invitation? To live without appeal. To find beauty not beyond the world, but within it, stripped of illusions. In Ladakh, that stripping happens naturally. The wind does it. The cold. The space between villages. The absence of distraction. There is no signal here—literal or metaphorical. No outside voice to tell you who to be. Just the path. And the next rise.

So, no, this is not a guide. It is a reflection. Not of what to do in Ladakh, but how to be there. Not a list, but a stance. Not a trail report, but a way of walking. Camus never walked this land, but he knew how to walk in the world. With eyes open. Without hope. And with love.

Against the Sartrean Gaze

It’s tempting, in an era obsessed with outcomes, to read a landscape like Ladakh through the Sartrean gaze—through the lens of meaning created by action. Jean-Paul Sartre, the other towering figure of French existentialism, insisted that man is defined by what he does. That freedom lies in commitment, in choosing, in responsibility. And yet, walking through this immense and indifferent terrain, I couldn’t help but feel that Camus had the stronger case here.

There is little room for grand engagement when you’re counting your breaths on a slope above Lingshed, trying not to faint. There is no revolution on a 4,800-meter pass—only dust, the press of boots into gravel, and the sound of your own blood rushing past your ears. Sartre would have asked me what I was doing about the world. Camus, I think, would have simply nodded, said nothing, and walked beside me.

The Himalayas do not require belief. They do not need your ideology, your causes, your philosophical constructs. They ask only one thing: that you keep moving. That you carry your load without appeal. That you walk. In this way, the journey becomes a moral posture—not through activism or discourse, but through perseverance. It is not a surrender. It is a refusal to surrender to illusion.

Camus believed in rebellion, but not revolution. His rebel does not overthrow the gods. He simply lives without them. In Ladakh, that rebellion takes the form of silence. Of restraint. Of knowing that no answer is coming, and choosing to act anyway. There is dignity in that. A dignity that Sartre’s restless engagement sometimes overlooked.

I met a monk once on the trail near Lamayuru. We walked together for half an hour. He didn’t ask me why I was there. He didn’t speak of karma or dharma or change. He only asked if I had enough water. That, in itself, was enough. That simple presence—like Camus’s absurd hero—made no claim, demanded no loyalty, offered no solution. It just walked beside me, quietly sharing the weight of the day.

To see Ladakh only through the eyes of purpose is to miss its lesson. The mountains are not waiting for you to explain them. They are not symbols. They are rock and sky and wind. In their presence, Camus’s ethics of silence feels not only appropriate—it feels necessary. To witness without imposing. To be without performing. To walk without needing to arrive.

The Sartrean gaze might look for meaning. Camus, instead, teaches us how to live in its absence. Not with despair, but with awareness. And in that, perhaps, we finally see what it means to be free.

The Human and the Rock

There is a moment, somewhere above 15,000 feet, when the line between effort and existence disappears. Your muscles no longer respond with the certainty of intention. Your lungs grasp for oxygen like hands fumbling in the dark. And the slope—endless, unrelenting—offers nothing back. No reward, no summit in sight, just more of the same. This is not tragedy. This is not even suffering. It is, in a strange and elemental way, simply the truth of the mountain.

I thought of Sisyphus then—not as a mythical figure, but as someone I might have known. A fellow trekker, perhaps. A quiet figure in a worn cap, pushing step after step upward, his breath visible in the morning frost. Camus said we must imagine Sisyphus happy. But up here, on a nameless pass between Chilling and Sumda, I could do more than imagine. I could feel it. There was, despite the burning in my thighs and the pressure behind my eyes, a kind of joy in the repetition. Not a joy of success, but of surrender. Of choosing the climb, even when the peak is irrelevant.

Mountains resist metaphor, but they invite reflection. In their sheer indifference, they become the perfect canvas for our inner monologues. The philosophical meaning of mountains lies not in what they are, but in what they demand from us. Attention. Humility. Patience. A refusal to escape. In a world obsessed with speed and outcome, the slow, steady ascent becomes an act of rebellion. The rock does not roll away from you—it waits for you to return, again and again.

There is no applause at the top of a Himalayan pass. No fanfare, no medals, not even a marker in some cases. Just a small pile of stones, maybe a flutter of prayer flags, and the sudden stillness of the wind. You stand there, chest heaving, and look out across a world that continues, unmoved by your effort. And yet, you feel full. Not with pride, but with presence.

Camus didn’t climb mountains. But he knew what it meant to confront a landscape that doesn’t care. He understood that the task itself—the push, the choice to rise, the act of moving forward despite futility—was what gave the moment its shape. In that sense, every trekker on a remote Ladakhi trail becomes an absurd hero. Not because they conquer the trail, but because they return to it without illusions.

And maybe that’s the point. Not to escape life through the mountain, but to meet it there—raw, quiet, and absurdly alive.

Epilogue: Camus Would Have Understood

I reached the final village three days later—a scatter of mud-brick homes beside a frozen stream, smoke curling from chimneys, prayer wheels spinning quietly in the wind. No one asked where I’d come from. No one needed to. In Ladakh, arrival is just another step in the journey. The real movement happened earlier, somewhere in the thinning air, somewhere between exhaustion and acceptance. And in that space, I had found something—not a revelation, but a kind of calm. Not enlightenment, but awareness. Something close to peace, but with sharper edges.

Camus never wrote about Ladakh. He never walked these passes, never stood on a ridge at 16,000 feet with the wind in his ears and the world spread like scripture below. But if he had, I think he would have recognized the place. Not the names, not the monasteries or the language, but the mood. The tone of it. The way it neither promises nor demands. The way it allows you to be, without explanation.

For Camus, the absurd was not a crisis—it was a condition. To see the world clearly, stripped of illusions, was not a burden, but a beginning. And here, among these mountains, it was easy to see clearly. The silence helped. So did the cold. The solitude, the repetition, the small beauty of every breath—it made you stop needing answers. It made you grateful for the questions.

In the end, perhaps Ladakh isn’t a place to be understood, but a place to be witnessed. To be felt. To be walked through slowly, with no intention of conquering it. Like Camus’s hero, you don’t need a reason to climb the hill. The climbing is the reason. The walking is the answer.

I left without saying goodbye to the mountains. I knew they wouldn’t miss me. And I wouldn’t miss them either—not in the usual way. They had already folded themselves into me, wordlessly. Like a line from a book you didn’t know you’d memorized. Like a truth you didn’t ask for, but now can’t unknow.

Camus never hiked in Ladakh. But he would have understood it. He would have understood the silence, the surrender, the choice to keep walking anyway.

Declan P. O’Connor is a columnist and essayist from Ireland.

He writes about solitude, place, and the quiet philosophy of walking.