On the longest day of last year, I visited what they call “the highest motorable road in the world.” But “road” might not be the right word. Nor is “pass.” Icicles hung from the mountainside, and along the winding path were memorials to soldiers who had “departed for heaven” after falling off the cliffs. The driver, with a red face and an indomitable spirit, crawled out of the rickety Toyota and began fiddling with the loose starter. This was not what I had hoped for at 18,350 feet. Pink fluid was leaking from the truck in front of us.

It was hard to believe that 90 minutes ago, we had been in Leh, the capital of Ladakh, 7,000 feet below. Now, it seemed we were in a snowfield. Tattered prayer flags hung between large rocks. Indian soldiers shivered in white tents. Not long ago, at 15,000 feet, a Sikh officer had started singing while checking passports, perhaps practicing the survival trick of maintaining a cheerful attitude at high altitudes. A nearby sign read, “Keep a cheerful attitude always.”

With the car almost intact, we began to move along the one-lane road toward the Nubra Valley. Marmots scurried across the path, and in the distance, we saw wild donkeys, kiangs. Behind them was the most pristine and surreal landscape I had seen in 25 years of travel. Vast plains stretched toward snow-capped mountains, with dry riverbeds spread like tears. In some places, fortress-like two-story white buildings gathered in greenery, quietly standing among apricot trees and willows. Two-humped Bactrian camels grazed on the sand dunes. The sky was so blue it hurt to look at. The desolate, sand-colored land seemed to be waiting for the Taliban at the distant pass.

As we rounded a bend, Diskit Gompa suddenly appeared before us, towering on the slope as if reaching for the heavens. We climbed up and stepped into a typical Buddhist city, with chapels smelling of centuries-old yak butter and white terraces offering endless views of the serene valley. Eventually, a single traveler appeared, as in every place we’d visited in Ladakh—one who would almost never come. He was a Tibetan living in Kabul.

“Strangely,” he said, confirming all my romantic suspicions, “the houses gathering in the valley, these desolate mountains, the snow-capped peaks—it feels like Afghanistan.”

Before visiting this high and dry region, often called “the last Shangri-La of the world,” situated on the border with Tibet, I knew I would see one of the great centers of Himalayan Buddhism. Books like Andrew Harvey’s brilliant “Journey in Ladakh” had told me I would see people living as they did centuries ago, in whitewashed houses amid barley and wheat fields irrigated by glacial meltwater. For the past 25 years, I had visited Bhutan, Nepal, the Indian Himalayas, and Tibet many times. But I had heard that Ladakh, known as “the land of high passes,” was the only place where an idyllic way of life still remained intact.

But When Entering an Imagined Romance

But when entering an imagined romance, reality and surprise are always found. Ladakh reminded me that it also borders Pakistan. That’s why the Indian soldiers were in the snow. Officially, Ladakh includes the Kargil region, which has a high Muslim population, with nearly half of its people being Muslim. More than anything, I was reminded that this place, with its pure blue skies, had been one of the most international trade hubs in the Himalayas for centuries. Traders carrying silk, indigo, gold, and opium passed through here on their way to other great caravan stops on the Silk Road.

On my first day in Leh, I stepped into the bustling center of town called Main Bazaar Street. Among the women quietly sitting on the sidewalk selling vegetables, I saw faces that reminded me of Lhasa, Herat, and even Samarkand. Near the large mosque on the street, there were Muslim elders and Indo-Iranian people with blue and green eyes, a legacy of Alexander the Great.

Walking around the dusty, mud-colored buildings that made up the only real settlement in the region, and seeing the ruins of palaces and temples placed to be protected by the surrounding cliffs and hills, I felt I was witnessing the intersection of two trade routes. Much of Ladakh lives in a different century than the one we know. The best hotel staff proudly offered “24-hour cold water,” and streetlights reached Leh in the third year of the Clinton administration. And despite the presence of internet cafes on every corner, messages sometimes arrived with notifications saying, “Your message was sent 235,105,786 seconds ago.” Due to its sensitive position between Pakistan and China, Ladakh was closed to foreign visitors by India until 1974, and even now, some roads remain closed by snow for at least seven months every year.

At the same time, the area gained a reputation as a “remote, undeveloped paradise,” and naturally, we bring our own images of paradise. Today, you can learn “traditional Thai massage” on the streets of Leh, dine at a Korean restaurant named Amego, participate in a “trekking meditation camp,” and hold video conferences at Login Himalaya. You can listen to a band from Athens, Georgia, playing at the Christian-run Desert Rain Coffeehouse, and watch “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End” at the Garden Restaurant just days after its premiere at Disneyland.

Ladakh: A Hidden Gem of Paradoxes

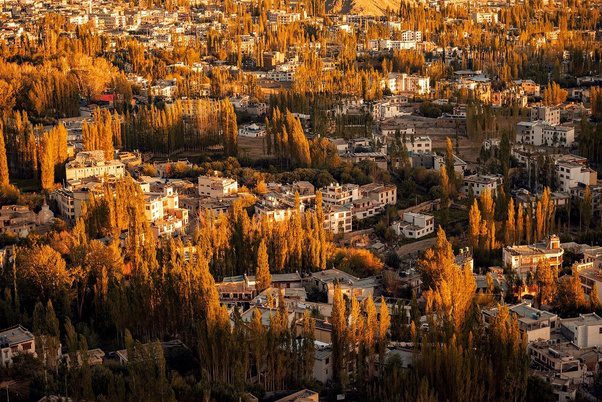

Compact, otherworldly, and profoundly magical, Ladakh is the latest hidden treasure that dramatically expresses the paradox of civilization and its discontents. Temples that defy gravity, small white stupas scattered across the parched earth, and tree-lined avenues from Leh were more beautiful than most things I had seen in Bhutan or Tibet. Yet, in our pursuit of such splendor, we bring a new restlessness to the people of Ladakh. The narrow streets of Leh are now filled with construction cranes and the engines of Suzuki cars, and their future hinges on whether they will package their past or discard it entirely.

One cloudless morning, I visited the elegant apartment at Stok Palace on the outskirts of town to meet Chogyal Jigmed Wangchuk Namgyal, the son of Ladakh’s last king. “From a development perspective, development always comes with planning,” said the leader in his forties. “When you look at Leh now, there is no individual thinking about the planning. Everything is very chaotic.”

The primary reason to visit Ladakh is its serene valleys and vast open spaces under a gleaming sky, where small houses are bound by mud-brick walls and tied together by the communal bonds inherited from ancestors. The second reason is the isolated gompas (monasteries) scattered across hills and mountaintops throughout the region. Red and white terraces, altars, chapels, kitchens, and schools spread out as eight-story complexes, exuding a presence unimaginable from the surrounding emptiness.

One day, I drove to Likir Gompa. Upon arrival, a monk emerged with a giant key straight out of a fairy tale. For a few small coins, he guided me from one locked chapel to another, each secured by a massive padlock. Inside the bare-floored chapels, light from the skylights illuminated dusty thangkas (Buddhist scrolls). The centuries-old murals depicted a cosmology of Buddhas, demons, and spirits, mapping out the landscapes of our inner worlds. Stepping back into the sunlight, only the sound of prayer flags fluttering in the wind could be heard in this rooftop region.

Traveling through Ladakh, such experiences repeat themselves. At Thiksey Gompa, just a 30-minute drive from Leh, you can participate in the monks’ chants at dawn. Further along the road, Hemis has a temple carved into the hillside, while in the opposite direction, Alchi village boasts a temple surrounded by gardens, adorned with frescoes in Kashmiri, Mughal, and even Central Asian styles.

Past Alchi, the one-lane road zigzags up a cliff, and with each heart-stopping turn, you remember why “gompa” means “lonely place.” Eventually, as you round a bend, Lamayuru Gompa appears atop the cliff. Signs read, “Welcome to Moonland View” and “Moon Palace Resort.”

Awe in Ladakh: A Journey Through Time

Having traveled the Himalayas for decades, I thought myself immune to being easily impressed. But this place made me gasp in wonder. I found myself looking at temples older than any wonder of the world, perched in more improbable places than the Potala Palace in Lhasa. Traveling these gravel roads, passing dilapidated “War Hero Fuel Stations” and signs proclaiming “Better Late Than Never,” I felt the finest joys of a traveler’s life. My driver, weathered and friendly, communicated with a smile and Ladakhi folk songs on a cassette tape.

Of course, for the people trapped in this curious world, it was far from exhilarating. “Life in Leh is boring,” the owner of a campsite in Nubra Valley assured me. Yet many outsiders come to Ladakh, bringing with them signs for Shabbat services and “Full Moon Parties.” Ladakh is becoming trendy even among middle-class Indian families, making locals realize their lives are changing. “In America,” the fast-talking entrepreneur continued, “it’s busy, 24/7. So much tension. Stress, stress, stress. That’s why Americans come here for peace and contentment. The weather’s hot or cold, everything’s boring, but life here is good.”

As one of the latest travelers to visit Ladakh, I couldn’t help but reflect on my presence here. The 50,000 tourists who visited in 2007 might seem few compared to a single game’s attendance at Shea Stadium. Still, for a region with only five times that many locals, it’s akin to America receiving 60 million foreign visitors annually. We climb, seeking quiet places where the airport is named after a high lama, and the only newspaper in the hotel dates back to November 8, 1999. Yet to the locals, we embody the modern century, and our longing for simplicity and silence looks like complexity and noise.

One early morning, I drove to Hemis to witness the Tsechu Festival, one of the significant events in the Ladakhi calendar. Upon arrival, a village spread out around the temple. Men with sharp cheekbones and girls sold necklaces, statues of Buddha, mystical scrolls, and CDs. Just as I pondered whether this was the flourishing of traditional culture, a Ladakhi pointed out that these goods were only for tourists. The locals gathered around a homemade roulette set up among the trees.

In the large courtyard of the temple, masked lamas performed slow, meditative movements and dances, depicting scenes from the life of Padmasambhava. At least 90% of the audience were foreigners, unable to grasp the symbolic actions’ meaning.

“Once, all the young men would go to the Tsechu Festival and have a big party,” explained Tsewang Dorje, a young, urban manager of a travel agency. “Now, it’s become just for tourists.” Many Ladakhi festivals traditionally occurred in winter, when Ladakhis weren’t working in the fields, but now they’ve been shifted to summer to attract foreign visitors.

As a result, Ladakh becomes a touchstone for the best and worst of what travelers bring. Travelers seem keenly interested in preserving the self-sufficient, traditional world they discover here. Helena Norberg-Hodge, one of the first Europeans to settle in Leh, arrived in 1975 and founded multiple organizations to preserve Ladakhi uniqueness, including an ecology center and a women’s alliance. Walking the grounds maintained by her women’s alliance just outside Leh, I saw workers constructing the first restaurant to offer authentic traditional Ladakhi cuisine, a challenging task given that local ingredients cost more than imported ones.

Thanks to people like Norberg-Hodge, signs reading “Say No to Polythene” are posted on Leh’s lampposts, and plastic bags are nearly banned in town. From the moment you arrive at the airport, signs promoting “compassionate tourism” and pamphlets urging, “Don’t buy multinational products… they destroy local economies worldwide,” greet you. Every day, debates on development take place at the women’s alliance, and other travelers speak of tourists as an unthinking juggernaut, akin to Mao’s People’s Liberation Army in Tibet.

Sometimes, the idea of foreigners protecting Ladakhis seems to carry a whiff of colonialism. It’s as if they discourage Ladakhis from enjoying the foreign culture that visitors themselves relish. Considering that Buddhism, which permeates this region, teaches all change comes from within, these external efforts sometimes seem a way to bring anger to a place more skilled at acceptance than we are. Yet, too much concern is certainly better than too little. Supporters of Norberg-Hodge have helped bring solar heaters, micro-hydroelectric plants, and low-cost greenhouses to Ladakh. “We’re not trying to tell Ladakhis what to do,” assured Nicolas Roucher, a young French volunteer working at the ecology center. “We just want to pose the question, ‘What is progress, what is development?’”

Almost everyone I spoke to in Ladakh, both foreigners and locals, told me there was a renewed interest in their heritage, Buddhism, and traditional medicine. They saw how appealing it was to the outside world and perhaps realized how profitable it could be. Over a hundred years ago, the British soldier-explorer Francis Younghusband described the Ladakhis as “typical traders of Central Asia… intelligent and shrewd, full of information.” Even today, you can see how this resourceful, seasoned trading culture has adapted to the latest influx of visitors from afar, much like it adapted to former commodity traders. (Ladakh’s old name was “Mangyul,” meaning “land of many people.”) Walking down the main street in Leh, you’ll notice that about half of the roughly 150 travel agencies include words like “eco,” “spiritual,” or “Tibet” in their names.

“I’ve never seen a homeless Ladakhi,” an English anthropologist who had worked intermittently in the region for about a decade told me. “Compared to the rest of India, Ladakhis are quite well-off.” When the tourist season ends, many Ladakhis go to work for the Indian army, maintaining a fragile peace along the glacial border disputed with Pakistan. The military and tourism have become the main sources of income—and joy—for the region.

As I ponder what my presence and that of other travelers bring to this long-isolated place, I remember Punchok Angchok, the nomadic driver who showed up every morning without complaint, ready to take us along the perilous unpaved roads. Four years ago, he had never left his village; he still couldn’t read or write. But since working for a travel agency, he had been able to send his 17-year-old son to a private school in Delhi.

One day, his son joined us on our journey. He wore a Nike shirt and a baseball cap and spoke fluent English. I noticed that despite his connection to the outside world, he was more conscious of his heritage. He reminded me to circle the temples correctly, prostrate fully before Buddha, and only dine at restaurants sponsored by the monasteries. He spent most of his summer break visiting his ancestral nomadic camp.

To me, Ladakh seemed like a place beautifully untouched compared to the modern Lhasa with its blue-glass shopping malls, the global village of city Nepal with its pizza shops and guesthouses, or the chic new hotels in secluded Bhutan. I couldn’t help but smile at the “He and She” shops scattered in Leh’s market, the prayer wheels on the main street that drivers spun every morning for blessings on our journey, and the sign outside Pizza de Hut that read, “Thank you for your visit. God bless you. Stay well. Goodbye.” To reach the town’s main tourist attraction, a nine-story ruined palace on a hill, one had to navigate through filthy alleys, following oil cans and telephone poles chalk-marked with “Way 2 Palace.”

Often, during such strolls, I was pushed aside by honking cars. One Saturday evening, I found myself the only foreigner among trendy Ladakhi teenagers at an “open mic” night at the Desert Rain coffee house. They sang all the lyrics to “Hotel California” fluently.

Yet, just a ten-minute walk from town, I reached shaded country paths where old-timers worked the fields or walked toward the temples, seemingly unaware of Paris—or Paris Hilton. One day, I discovered musicians playing between poplar trees and teams in elegant black robes competing against those in graceful white robes in traditional archery. The scores were chalked on blackboards, and the teams danced before and during the match.

One day, I read in the local English-language newspaper, The Magpie, about a brave villager who risked his life to save two calves and a lamb from a snow leopard. After a five-hour drive over the world’s highest motorable road, I found the Hunder gompa closed. “The head lama is not here this season,” a local explained. “Many insects die this time of year, and every household prays for them.”

Listening to him, I recalled my time in Dharamsala just a year ago. I had asked the Dalai Lama’s chief secretary, who had traveled more than anyone I knew, which place had moved him the most in his 40 years with the Dalai Lama. He had been to the White House, the Vatican, and had traveled to Mongolia, Jerusalem, South Africa, and Lapland with the Dalai Lama.

His eyes took on a distant look, recalling a moment in Ladakh. “Just looking out over the valley—the stillness, the faraway river, the temples,” he said.

For him, Ladakh was the closest place to the Tibet he had known as a boy, a Tibet he might never see again. But for me—and everyone else—Ladakh is a way to reclaim something lost, and once experienced, it feels modern, vibrant, like tomorrow.