The Wind Whispers in Many Languages

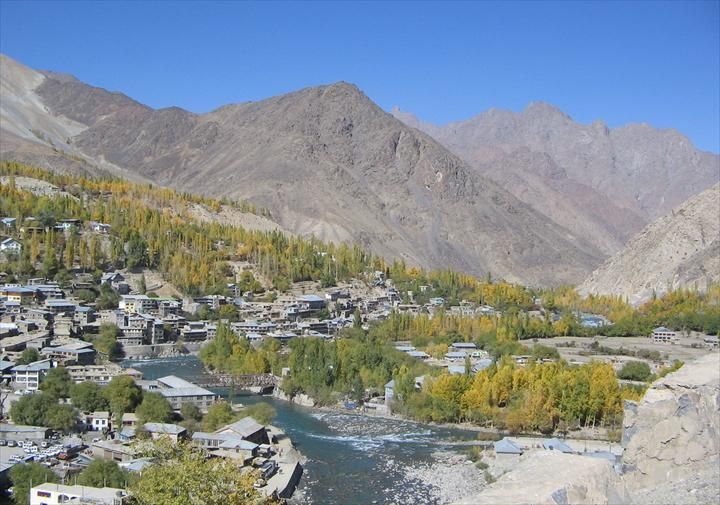

I arrived in Leh not as a tourist, but as a quiet listener. The kind of listener who believes that places speak, if only one stands still long enough. And Ladakh — this land of stone monasteries, sky-bound passes, and prayer-flagged winds — has learned to speak many languages across centuries. One of those, though often forgotten, carries a European accent.

In the soft golden light of early morning, I wandered through Leh’s old town, guided not by maps, but by instinct and the scent of warm bread rising from a bakery tucked beneath an ancient wooden balcony. A young monk passed me, his maroon robes swirling around sandaled feet, and I wondered — who walked here before us? Who whispered to these walls in tongues far from these mountains? This column begins with that question.

Ladakh is typically framed as a Buddhist highland nestled between India and Tibet, a place of monasteries and meditation. But peel back the layers of stone and prayer, and you’ll find the ghost-prints of European boots, the fading ink of Latin-script letters, and the silent testimony of travelers, cartographers, and missionaries who came here with compasses, crucifixes, and curiosity.

In the 17th century, long before Ladakh became a stop on Instagram’s global circuit, Jesuit priests crossed the Himalayas, hoping to convert souls and document a land that Europeans had only heard of in whispers. Later came the explorers — British surveyors and French naturalists — driven by empire and the thirst for discovery. With them came a reshaping of Ladakh not only in maps, but in imagination. They saw it not as peripheral, but pivotal — a strategic highland crossroads between Central Asia, Tibet, and the Indian plains.

These European encounters left behind more than journals and footprints. They altered the way Ladakh was seen, both from within and beyond. Today, that legacy remains hidden in weather-worn stone churches, archived correspondence in European libraries, and place names slightly misspelled in colonial documents. The European influence in Ladakh is subtle but enduring — stitched into the fabric of trade routes, politics, and even pilgrimage.

As I sat beside a crumbling wall painted in ochre and faded turquoise, I listened to the wind brushing across the roofs. I imagined it carried Latin prayers alongside Buddhist chants, British dispatches alongside Ladakhi folklore. I began to understand: Ladakh’s story is not a monologue. It’s a polyphonic tale where European connections hum beneath the surface, waiting to be heard.

This journey is not just about retracing paths, but about revealing echoes. In the chapters to come, I’ll walk you through stories that tie Ladakh to Europe — through missions and maps, relics and rivalries. If you’ve ever wondered what brings a French botanist, a German priest, or a British general to this corner of the sky, read on. The mountains remember.

The Jesuits Came First: Crosses in the Shadow of Stupas

Before the cartographers, before the diplomats and soldiers, came the missionaries. In the early 17th century, they arrived not with weapons, but with crosses and quiet resolve. The Jesuits — men of faith, language, and astonishing endurance — crossed treacherous Himalayan passes with a singular vision: to bring Christianity to the rooftop of the world. Their journey was not just spiritual. It was also deeply political, geographical, and, ultimately, historical.

One name still echoes through the corridors of European religious exploration in Asia: Ippolito Desideri. Born in Tuscany, he reached Tibet in 1716 after passing through Kashmir and Ladakh. His records speak of snow-blind marches, theological debates with Buddhist monks, and the striking hospitality of Ladakh’s people. Though his mission was ultimately halted by ecclesiastical politics back in Europe, his presence in Ladakh marked a beginning. He was not alone. Portuguese Jesuits like António de Andrade had passed through these same valleys earlier, and German Moravian missionaries would follow.

Here, in the heart of the Himalayas, the encounter between the sacred and the foreign unfolded not in conflict, but in cautious conversation. A stone chapel once stood near Leh’s outskirts — its ruins now absorbed by apricot trees and curious schoolchildren. In Hemis, Stok, and other villages, Ladakhis still recall the “padris” — Christian priests who spoke a strange tongue, offered care, and left behind songs that no one remembers the words to, but whose melodies still linger in oral folklore.

What drew these European missionaries to Ladakh? For some, it was the belief that the kingdom was a hidden gateway to Tibet — a final frontier of the Christian world’s evangelical imagination. For others, Ladakh was simply a waystation between the Mughal court and the Tibetan plateau, an ideal point from which to observe, study, and possibly influence. The Jesuit missions in Ladakh were short-lived, but their ambition was vast — spiritually, geographically, and culturally.

I visited a crumbling archive in Leh, guarded by a Ladakhi librarian who traced the inked pages of Desideri’s translated texts with reverence. One line caught my eye: “In this high kingdom, all things feel closer — to the heavens, to truth, to history.” It felt as though he were speaking to me, across three centuries, across continents. The European priests in Ladakh weren’t just messengers — they were the first historians, mapping not only land but worldview.

There is something deeply human in their story — of yearning, of misunderstanding, of trying to build bridges between belief systems as different as snow and fire. And while their efforts to convert Ladakh were ultimately unsuccessful, their legacy remains as whispers in the wind, crosses in the shadow of stupas. That juxtaposition, quiet but undeniable, is where this chapter of Ladakh’s European colonial history truly begins.

In the next chapter, we’ll follow the footsteps of generals and spies, as the European footprint in Ladakh takes a more strategic and dangerous turn — into what came to be known as “The Great Game.” But for now, pause here, among ruined chapels and half-remembered prayers, and consider this: sometimes, empire begins not with conquest, but with a whispered Amen.

The Jesuits Came First: Crosses in the Shadow of Stupas

Before the cartographers, before the diplomats and soldiers, came the missionaries. In the early 17th century, they arrived not with weapons, but with crosses and quiet resolve. The Jesuits — men of faith, language, and astonishing endurance — crossed treacherous Himalayan passes with a singular vision: to bring Christianity to the rooftop of the world. Their journey was not just spiritual. It was also deeply political, geographical, and, ultimately, historical.

One name still echoes through the corridors of European religious exploration in Asia: Ippolito Desideri. Born in Tuscany, he reached Tibet in 1716 after passing through Kashmir and Ladakh. His records speak of snow-blind marches, theological debates with Buddhist monks, and the striking hospitality of Ladakh’s people. Though his mission was ultimately halted by ecclesiastical politics back in Europe, his presence in Ladakh marked a beginning. He was not alone. Portuguese Jesuits like António de Andrade had passed through these same valleys earlier, and German Moravian missionaries would follow.

Here, in the heart of the Himalayas, the encounter between the sacred and the foreign unfolded not in conflict, but in cautious conversation. A stone chapel once stood near Leh’s outskirts — its ruins now absorbed by apricot trees and curious schoolchildren. In Hemis, Stok, and other villages, Ladakhis still recall the “padris” — Christian priests who spoke a strange tongue, offered care, and left behind songs that no one remembers the words to, but whose melodies still linger in oral folklore.

What drew these European missionaries to Ladakh? For some, it was the belief that the kingdom was a hidden gateway to Tibet — a final frontier of the Christian world’s evangelical imagination. For others, Ladakh was simply a waystation between the Mughal court and the Tibetan plateau, an ideal point from which to observe, study, and possibly influence. The Jesuit missions in Ladakh were short-lived, but their ambition was vast — spiritually, geographically, and culturally.

I visited a crumbling archive in Leh, guarded by a Ladakhi librarian who traced the inked pages of Desideri’s translated texts with reverence. One line caught my eye: “In this high kingdom, all things feel closer — to the heavens, to truth, to history.” It felt as though he were speaking to me, across three centuries, across continents. The European priests in Ladakh weren’t just messengers — they were the first historians, mapping not only land but worldview.

There is something deeply human in their story — of yearning, of misunderstanding, of trying to build bridges between belief systems as different as snow and fire. And while their efforts to convert Ladakh were ultimately unsuccessful, their legacy remains as whispers in the wind, crosses in the shadow of stupas. That juxtaposition, quiet but undeniable, is where this chapter of Ladakh’s European colonial history truly begins.

In the next chapter, we’ll follow the footsteps of generals and spies, as the European footprint in Ladakh takes a more strategic and dangerous turn — into what came to be known as “The Great Game.” But for now, pause here, among ruined chapels and half-remembered prayers, and consider this: sometimes, empire begins not with conquest, but with a whispered Amen.

The Great Game: Where Empires Played Chess at 10,000 Feet

The wind changes in Ladakh — subtly, but decisively. And so does the nature of Europe’s presence. If the missionaries came with prayers, the next arrivals brought maps, treaties, and a very different kind of faith: faith in empire.

In the 19th century, Ladakh found itself unwillingly invited to one of the most secretive and high-stakes games of the century — a silent, strategic struggle between the British and Russian empires for control over Central Asia. Historians now call it the Great Game. But for those who lived here — farmers in Nubra, monks in Diskit, traders in Leh — it wasn’t a game at all. It was the slow, unsettling arrival of surveillance, suspicion, and the politics of geography.

Ladakh, poised at the roof of the world, became a pawn in this global rivalry. The British colonial strategy in the Himalayas was clear: create a buffer zone between Russian influence and British India. And so they sent their men — not soldiers, but surveyors, linguists, spies dressed as pilgrims. These “pundits” recorded topography with disguised instruments hidden in prayer beads, counted steps to measure distance, and memorized mountain passes. The knowledge they gathered would help redraw the maps of Asia — and reshape the fate of Ladakh.

In the archives of the Royal Geographical Society in London, I once read the field notes of a British officer who had crossed Zojila Pass in 1860. He wrote, “Ladakh is a political whisper, not yet a storm.” He wasn’t wrong. By the 1840s, Ladakh had been annexed by the Dogras under British encouragement. The politics of the British Raj stretched all the way to Leh, cloaked in diplomacy and dusty boots.

And yet, the Russian threat was more imagined than real. No Russian army ever descended the passes into Ladakh. But the fear of Russian expansion haunted drawing rooms in Simla and London. To counter this ghost, Britain built roads, installed political agents, and fostered ties with local rulers. A strange, quiet militarization of the mountains unfolded, where every yak caravan might be carrying messages, and every lama might be a spy. The Russo-British rivalry in Ladakh was theatre — but its consequences were lasting.

Even today, Ladakh’s borders carry the scars of this imperial anxiety. Lines drawn during these years — between British India, Tibet, and the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir — have left their mark not only on paper, but on people. They shaped trade, religion, movement — and memory. The geopolitics of Ladakh became embedded in its soil, like forgotten footsteps across a frozen pass.

On a recent visit to an old British-built rest house outside Kargil, I ran my hand across its cold stone walls. The building, long abandoned, is now home to sheep and silence. But it once hosted officers, maps splayed across wooden tables, their fingers deciding the fate of valleys they’d never truly understand. Here, European influence in Ladakh took on a colder tone — one of control rather than communion.

Next, we’ll descend into the world of lines and legends — into the art and politics of colonial mapping. Because as any seasoned traveler knows, how we draw a place is how we begin to claim it. And Ladakh, in the 19th century, was being drawn with imperial ink.

Maps, Myths, and the Making of Borders

In Ladakh, maps have always been more than just guides — they are instruments of power, of imagination, and, sometimes, of misunderstanding. Long before GPS coordinates and satellite imaging, this high-altitude world was sketched by hand, by travelers with frozen fingers and imperial ambitions. And it was through these fragile sheets of parchment and ink that Europe began to redefine Ladakh — not only in geography, but in identity.

The British, particularly during the height of the 19th century, understood that to rule a land, one must first know it — or at least believe they do. The colonial mapping of Ladakh became a powerful act of claiming space. Survey missions were dispatched, disguised as trade caravans or Buddhist pilgrims. The “Great Trigonometrical Survey of India” crept higher and higher into the mountains, its men measuring altitudes and valleys with instruments cloaked in incense and prayer flags.

One of the most symbolic moments in Ladakh’s geopolitical reshaping came with the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846. With the stroke of a quill in a British colonial office, the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir — including Ladakh — was sold to Gulab Singh for 7.5 million rupees. It was an exchange of vast landscapes for paper currency, a transaction that would go on to shape regional disputes for over a century. Few maps before that treaty showed Ladakh in such bounded clarity. Few after left it untouched.

The Europeans saw Ladakh through the lens of empire — a land to be measured, analyzed, and partitioned. This approach often clashed with the Ladakhi worldview, where mountains are sacred, rivers are stories, and boundaries are less rigid than relationships. And yet, British cartographers drew hard lines across snowfields, giving names to passes that already had names, often mispronounced or mistranslated. The result was a geography of omission as much as inclusion.

I once found an 1890s British map of Ladakh in a dusty archive in Marseille. The Zanskar River was misaligned. Stok village was spelled “Stoke.” Pangong Tso was split awkwardly by a border that didn’t exist on the ground. Still, the map bore the seal of the Royal Engineers, stamped with confidence. These European cartographers in Ladakh didn’t just map terrain — they mapped intention.

But it wasn’t just the British. French botanists charted floral zones. German linguists recorded dialects. Each map told its own story, revealing not just where things were, but how outsiders wished to see them. The myths they carried — of an untouched Shangri-La, a Buddhist utopia, or a buffer zone between empires — were layered over every contour line and place name. The mythmaking of Ladakh’s borders was as influential as the surveys themselves.

Today, many of these maps reside in European museums and academic collections. Few locals have ever seen them. And yet, their legacy shapes Ladakh’s current realities — its geopolitical tensions, its administrative divisions, even its tourism circuits. What was once a spiritual landscape has been reframed as a strategic one, its valleys transformed into markers of control.

As I gazed at a modern political map in a Leh guesthouse, brightly colored with India’s borders, I thought of all the other versions that once existed — the ones with blurred lines, handwritten legends, and the scent of old ink. Ladakh has always been many things to many people. For Europe, it was a canvas. But for Ladakhis, it remains a home — one that defies easy demarcation.

Next, we leave the world of paper and lines behind, and return to the bazaar — where traders and travelers once exchanged silk, salt, and stories in many tongues. Because while maps may draw borders, trade has always found ways to cross them.

Silk Road Crossings: When Traders Spoke in Many Tongues

Before there were borders, there were boots on dust. The traders came long before the mapmakers, and Ladakh — perched at a crossroads of ancient civilizations — welcomed them all. Horses loaded with indigo and cinnamon, yaks bearing coral, wool, and copper, men in robes and turbans murmuring in Turkic, Persian, Tibetan, Kashmiri, and, yes, even French and Italian. This was the trans-Himalayan trade route, and it pulsed through Ladakh like blood through a beating heart.

Europe’s connection to this network was not merely abstract. From the 17th to the 19th century, intrepid explorers and merchants from the West arrived in Leh, driven by dreams of distant empires and whispered rumors of Buddhist kingdoms hidden in the clouds. Among them were French traders, Italian cartographers, and even Polish refugees seeking sanctuary and opportunity in the East. Their names may be footnotes in the grand chronicles of history, but their footprints remain embedded in Ladakh’s bazaar stones.

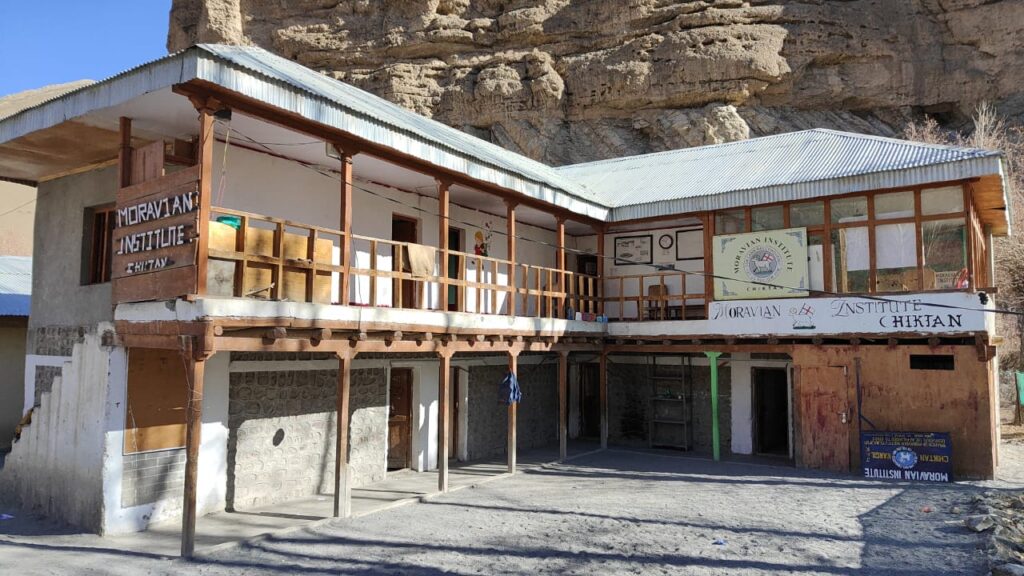

Walking through Leh Market today, it takes only a little imagination to see the ghosts of these travelers. Imagine a merchant from Lyon exchanging woolen shawls for turquoise. Picture an Austrian botanist carefully labeling alpine plants collected near Khardung La. In the mid-1800s, the Moravian Church — primarily German and Swiss — established a mission station that also functioned as a trade outpost. Alongside religion, they brought clocks, microscopes, books, and European medicinal remedies, introducing a different kind of exchange: that of knowledge.

The Silk Road history of Ladakh is one not only of goods, but of gestures — nods, handshakes, shared bread. At the convergence of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and Tibet, Ladakh became more than a geographic space. It became a conversation. And Europe, curious and hungry, wanted to be part of it.

I met an elderly weaver in Basgo who told me his grandfather once traded pashmina with men who came “from far beyond the great river,” pointing vaguely west. They brought coins with strange faces and fabrics that shimmered “like moonlight.” These weren’t colonial administrators or cartographers — they were cultural emissaries with sacks instead of suits, learning about the Himalayas one market stall at a time.

But as the 20th century approached, these informal exchanges began to thin. Borders hardened. Empires collapsed. Trade routes fell quiet. The European traders in Ladakh disappeared, leaving behind fragments — a rusted coin, a German inscription inside a prayer book, a recipe for apple vinegar scribbled in Italian.

And yet, the legacy of that multilingual, multicultural bazaar still hums through Ladakh. You hear it in the variety of Ladakhi dialects, many of which carry traces of Persian and Turkic intonation. You see it in old family homes, where faded European prints hang beside thangkas. And you feel it — especially if you’re from Europe — in the strange sense of recognition. A quiet echo.

Next, we will explore what remains of that presence. Not in bustling markets, but in lonely structures — abandoned mission schools, archived letters, forgotten chapels. Because while trade built connections, it was European institutions that tried to make them last.

The Relics Remain: Churches, Archives, and Echoes in the Dust

Empires may dissolve, and trade routes may vanish into sand and snow, but stone often outlives intent. In Ladakh, some of Europe’s quietest legacies are not written in history books, but rather crumble gently behind barley fields, gather dust in locked trunks, or echo faintly through half-forgotten prayers. These are the relics of European presence in Ladakh — modest, elusive, and deeply human.

Tucked behind the Leh Polo Ground stands a modest structure with arched windows and sun-faded wooden beams. Once, it was a mission school established by the Moravian Church — a Protestant movement with roots in what is now the Czech Republic and Germany. By the late 1800s, Moravian missionaries had arrived in Leh and Shey, bringing with them not only Bibles but also education, medicine, and printing presses. Their mission buildings doubled as clinics and schools, offering services to Ladakhis regardless of faith.

Today, the building is locked. Weeds creep through the stones. But if you peer through the glassless window, you might see old chalkboards, iron bedframes, and remnants of a European vision for the high Himalayas. It wasn’t empire in the classical sense — no armies, no taxes — but it was a quieter form of occupation: one of ideology, charity, and structure.

Further down the valley in Khalatse, a local family showed me a letter kept in a carved box. Written in flowing German script, it was addressed to a missionary named Müller and dated 1903. The envelope, browned with time, carried stamps from Basel and Calcutta. Inside were simple lines: news from home, prayers for strength, and a reminder that “God’s work is slow but steady in the mountains.” This European correspondence in Ladakh offers a rare, emotional glimpse into the hopes and endurance of those who lived between two worlds.

Beyond the buildings and papers, there are other traces. A British sundial, half-buried in a village near Stok. A wooden cross discovered in a monastery storehouse, its presence neither explained nor removed. In Alchi, an old monk once showed me a beautifully preserved Latin missal. “This came with the men who wore black and spoke gently,” he said. “They left long ago, but we keep it because it has power.”

The European artifacts in Ladakh do not speak loudly. They murmur. A school bell rung by Ladakhi hands. A herb garden planted with Swiss seeds. An old French grammar book once used by a student who later became a monk. These are not museum pieces — they are living echoes woven into the everyday.

What strikes me most, walking through these spaces, is how they blur the binary of East and West. They are not “foreign,” not quite “native.” They simply are — pieces of a shared past that didn’t conquer, but conversed. For the European traveler today, these places invite not nostalgia, but humility. We were here. We tried to help, to teach, to understand. And though we left, something remained.

In our next and final section, I’ll reflect on what it means — as a European — to walk through this landscape layered with intention, imagination, and unfinished sentences. Because in Ladakh, the past is not dead. It is a companion on the trail.

A Pilgrim’s Reflection: Searching for Europe in Ladakh’s Stones

There’s a silence in Ladakh that speaks. It’s not the absence of sound, but the presence of something else — something older than war, deeper than empire. I felt it most clearly not in the monasteries or in the mountains, but while sitting on a stone wall in the village of Temisgam, watching apricot blossoms fall like snow.

Behind me, children were reciting Ladakhi poems. Ahead, a herd of goats kicked up golden dust as they climbed toward a ridge where prayer flags danced like restless thoughts. And somewhere in between — in that quiet space — I heard Europe whisper.

The European footprint in Ladakh is not always visible. It hides beneath layers of prayer flags and barley fields, between old German books and forgotten British milestones. But if you walk slowly — if you listen — it begins to appear. A curvature of architecture, a word in a local dialect, a name in a registry written in spidery Latin script. This isn’t nostalgia. It’s recognition. A feeling of belonging in a place where you’re clearly foreign.

I came here not to find Europe, but to understand Ladakh. Instead, I discovered that the two were never so separate. The cultural exchanges between Europe and Ladakh were often imperfect, sometimes naive, but always human. And those human gestures — whether a Jesuit’s sermon, a French mapmaker’s sketch, or a Swiss nurse’s bandage — linger longer than any border.

To my fellow Europeans reading this: when you walk through Ladakh, you are not just tourists. You are, perhaps unknowingly, participants in a long, unfinished story. You are walking in the footsteps of those who came before — explorers, misfits, linguists, missionaries, even dreamers — each one leaving behind something small, something forgotten, something real.

As the world becomes noisier and faster, there is something quietly radical about places like Ladakh — places where memory is stored in stones and meaning is slow to reveal itself. The legacy of European connections in Ladakh isn’t loud or proud. It’s careful. It’s cautious. And, in its own way, it’s beautiful.

This is why I return, again and again — to walk the same roads, to sit in the same sun, to remind myself that history is not always written in capitals. Sometimes, it’s inscribed in dust, in a child’s name, or in the way a Ladakhi host boils tea the same way her grandmother did when German visitors sat on this same floor.

Ladakh does not need us to tell its story. But perhaps, by listening well, we can learn how to tell our own differently. Less from maps. More from memory.

About the Author|Elena Marlowe

Elena Marlowe is an Irish-born writer currently residing in a quiet village near Lake Bled, Slovenia.

Her work explores the intersections of forgotten histories, cultural memory, and human landscapes across the edges of Europe and Asia.

With a background in historical anthropology and literary travel writing, Elena has spent the past decade tracing the subtle footprints of empire, exile, and faith in places where history is still spoken in whispers — from Ladakh’s high passes to the Adriatic coast.

She believes that stories live in stone as much as in books, and that the most meaningful journeys begin when we choose to listen.

When not writing, she enjoys collecting antique maps, baking walnut bread, and hiking through landscapes that carry more past than present.

Her columns aim not to explain a place, but to invite readers to see it with new eyes — with reverence, curiosity, and the patience to pause.