Walking into the Silence of Ladakh’s High Valleys

By Elena Marlowe

Introduction: The Thin Air of Thought

The First Breath in Ladakh

When one arrives in Ladakh, it is not the grandeur of mountains that first presses upon the senses, but the pause between breaths. The thin air makes the lungs work harder, every inhale deliberate, and yet, in that struggle for oxygen, there is an unexpected clarity. The silence that settles here is not an absence but a presence—thick, resonant, alive. It is the kind of silence that does not intimidate, but instead stretches out, inviting one to step into it like an open field. Travelers who descend into Leh often remark on the shock of the landscape: ochre ridges, shadows of snow across granite, the sudden brilliance of the sky. But what lingers far longer than any visual memory is the rhythm of stillness. It is this stillness that reshapes time, loosening the grip of schedules and replacing it with the cadence of steps. Walking in Ladakh becomes a profound experience.

This introduction is more than scene-setting. It is an invitation into the heart of Ladakh, where walking is not merely movement but meditation. The traveler learns quickly that distances are deceptive: what seems like a short stroll may demand long hours, the terrain asking for patience. And patience is rewarded—not with the bustle of markets or the flash of monuments, but with the quiet knowledge that one is walking inside a living philosophy. In Ladakh, each footstep becomes both prayer and question, an inquiry into how we might inhabit the world differently. The thin air alters not only the body’s pace but the mind’s, too, allowing thoughts to drift as freely as prayer flags in the wind.

Walking in Ladakh offers a unique perspective on the world, revealing the depth of its culture and landscape.

Prayer Flags and Empty Skies: Symbols in Motion

The Wind as Philosopher

High on the ridges, lines of prayer flags whip in the Himalayan wind, each a fragment of color suspended between earth and sky. Their flutter is not merely decorative; it is a philosophy unfurling with each gust. The fabric carries words of hope, wisdom, and remembrance, scattered into the vastness above. To walk past them is to be reminded that belief can be light, not heavy—woven into air rather than carved into stone. The wind, relentless yet playful, becomes a philosopher itself, teaching that permanence is not necessary for meaning. The flags fray, fade, and eventually disintegrate, but their essence is carried onward, unseen but present.

For the walker, these flags are a mirror of the journey. Each step is temporary, each footprint soon erased by dust or wind, and yet the act of walking creates a thread of memory that persists within. Standing before them, one may recall the ancient Stoics who counseled acceptance of what is beyond control, or Eastern teachers who spoke of surrender as strength. The flags show us both: that our efforts dissolve into larger currents, and that there is peace in knowing this. In Ladakh, where the landscape is so vast that the self feels small, such reminders are not abstract—they are tangible, blowing against the skin, reminding us that our thoughts, too, can be loosened and carried away if we let them.

Color, Faith, and Fragile Fabric

Against the immense blue of Ladakh’s skies, the colors of the prayer flags burn bright: red, blue, green, yellow, white. Each is meant to represent an element, a balance of forces seen and unseen. Yet beyond their ritual meaning, what captures the traveler is their sheer fragility. A strip of cloth, vulnerable to tearing, somehow becomes a conduit between mortal hands and eternal heavens. As one walks, these flags appear on ridges, at mountain passes, even tied to solitary cairns. Each one whispers of those who came before—pilgrims, shepherds, wanderers—each leaving behind something slight, but potent.

The fragility of fabric reflects the fragility of human endeavor. Journeys end, lives fade, but the trace remains in the air, stitched into memory. It is this combination of strength and delicacy that lends Ladakh its particular resonance. Walking beneath these sky-born ribbons, a traveler feels both rooted in the earth and dissolved into the horizon. And perhaps that is the lesson: that beauty does not require permanence, that meaning need not be carved into monuments but can be as fleeting as cloth unraveling in the wind.

Walking as Philosophy: Lessons from the Path

Solitude and the Mountain Mind

Solitude on a high-altitude path in Ladakh is not the same as being alone in a city park. Here, distance feels elastic. Peaks that look a morning away remain on the horizon by late afternoon. Valleys fold into one another with the quiet certainty of a well-read book, and a walker discovers that the most faithful companion is the sound of their own breath. In this rarefied air, thoughts declutter. The concerns that travel so loudly in daily life become moth-like—still present, yes, but small, soft, manageable. This is where walking in Ladakh takes on its deeper meaning. The body negotiates thin air, and the mind, relieved of its usual traffic, begins to notice the micro-events of the trail: the way pebbles roll underfoot and stop as if listening; the way the wind climbs a slope, lifts a corner of a scarf, and then disappears with no intention of return.

As the hours compound, solitude acquires a texture that is neither austere nor indulgent. It becomes a spacious medium through which the world is conducted. You find you are not really alone—ravens patrol the thermals; a distant yak bell tolls an unfamiliar hour; the river, narrow as a thread in the sand, flickers like a thought that hasn’t yet found words. In such company, reflection comes easily. The act of placing one foot and then the other becomes a metronome for thinking. You experiment with questions: What is endurance if not a pact with the unknown? What is comfort, and who defined its borders so narrowly? You notice how little you actually need: a reliable bottle, a shawl at dusk, a place to sit and watch the sky bruise toward evening. Solitude here is not a deficiency of society but a surplus of attention. And once you learn how to carry that attention, it travels with you, like a private climate that makes room for reflection even when the world resumes its volume.

Stillness vs. Motion

To walk is to set a small rebellion in motion: against rush, against distraction, against the idea that value must be measured in speed. The paradox is delicious—walking in Ladakh requires motion to achieve stillness. The mountains demonstrate the principle. They do nothing and yet transform you; they appear immovable, and yet hour by hour their colors migrate with the light. A ridge at noon is brass; by evening, ink. The walker learns to imitate the mountains: keep moving while cultivating a core of quiet. Footsteps supply the rhythm, breath supplies the chorus, and the surrounding world supplies the melody of change.

On certain days the wind sews and unsews the clouds, and a pass that looked within reach wavers, as if the landscape were breathing too. This is the moment to practice a more patient traveling—where distance is not conquered but befriended. You begin to recognize the many synonyms of quiet: hush, pause, lull, interval, reprieve. You hear them in the rustle of prayer flags and in the soft click of your trekking pole on stone. Stillness becomes an inner arrangement rather than an outer condition. Even when the track rises and your lungs protest, you can choose to dwell in a pocket of calm attention, an inner veranda opening onto a high valley. The reward is not a summit photograph but a quality of presence that is portable. It’s what lets you sit later in a village yard as the kettle hisses and taste the tea as if it were a first edition of warmth. Motion, judiciously made, is the craft by which the mind keeps house for stillness. And if you must carry home a single lesson, let it be this: walking is not merely a way of getting somewhere; it is a way of being where you already are.

Cultural Encounters Along the Way

Villages and Valleys

In Ladakh’s valleys—Sham, Nubra, and those unnamed by most maps—villages appear like afterthoughts of water. Follow the irrigation channels and you will find willow shade, orchards, barley terraces, and small courtyards where life is calibrated to altitude and daylight. Walking in Ladakh through these spaces reeducates a traveler’s sense of scale. A “short” crossing becomes a mediation between sunlight and shadow, between the raw, lunar rock and the sudden green geometry of fields. You learn quickly that hospitality is a form of architecture: a gate left open, a low wall that invites sitting, a ladle dipped into a shared pot. In such places, conversation moves at the speed of trust; it begins with tea, sometimes with silence, and often with a smile that says, stay as long as the water boils.

A walker who is attentive notices the craftsmanship of daily life: the pattern of stacked stones holding heat through evening, the careful way a ladder is angled against a roof, the tidy economy of tools leaned by a doorway. The valleys are not scenic backdrops but active participants in the choreography of living. Children cut across alleys carrying bread wrapped in cloth; a grandmother reads the weather with a glance at the ridge; a young man patches a tire while discussing snowlines. Here, guidance comes unannounced. Someone will sketch a line in the dust with a stick—turn at the apricot tree, keep the river to your left, the track climbs after the second chorten. Directions assume you are part of the land’s grammar. And so you are, for a while: a pronoun threaded through the sentence of the valley. This is cultural encounter as apprenticeship. You are not acquiring souvenirs; you are borrowing ways of noticing. The lesson to take with you is not that “people are kind” (they are) but that kindness is a spatial practice—how humans edit the world to make room for one another.

Monasteries as Anchors of Silence

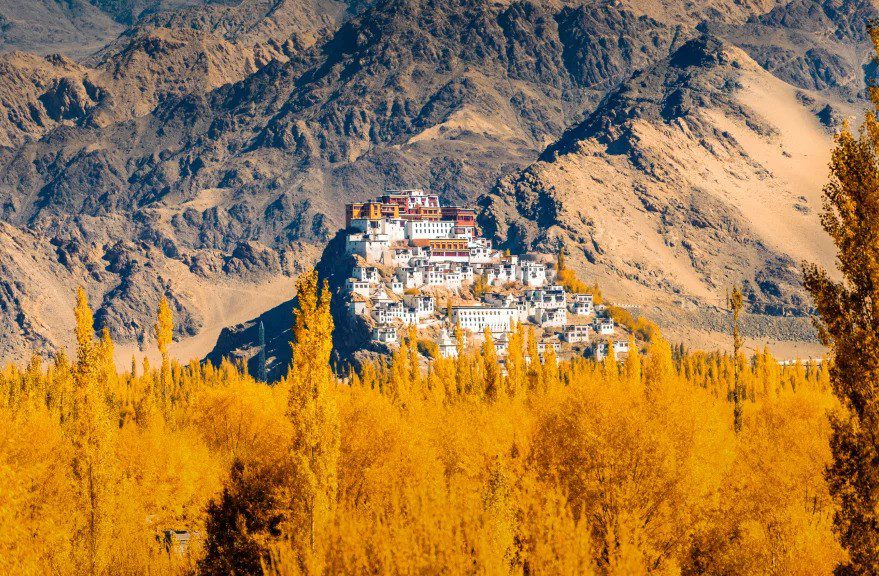

Approach a monastery on foot and you will feel the difference. It is not only elevation; it is orientation. Buildings align with ridges and sky as if drawn on a compass of devotion. Whitewashed walls gather the sun. Courtyards receive wind in measured portions. The footpath narrows, turns, and then opens like a held breath—an architectural gesture that prepares you to listen. The first sound is often small: the rasp of a door, the brush of a robe, a bell decoding the afternoon into patient moments. Inside, murals deepen the air. Colors seem to illuminate themselves from beneath, with deities and guardians performing a theater of compassion and ferocity. It is tempting to treat such places as galleries for the camera; walking in Ladakh teaches a different etiquette. Stand, breathe, wait. The space will make its introduction.

The most potent encounters are not staged. A novice crosses the courtyard at the angle of a bird’s shadow; an old monk pauses to tie a prayer flag with a steadiness learned over decades; butter lamps correct the darkness one quiet flame at a time. Monasteries teach a grammar of attention. They ask the visitor to move from sightseeing to sight-being, which is to say, to let the eye rest long enough for understanding to arrive unhurried. Anchored thus, silence becomes articulate. You notice how the building edits wind and light, how the mountains lean closer as if to eavesdrop on the chant. When you leave, descending the path back toward the valley, the world feels rephrased. Even the dust speaks more softly. You carry with you not a doctrine but a posture: shoulders lowered, steps measured, mind a little wider at the edges. And later, on the open trail, when prayer flags argue playfully with the weather, you realize that the monastery has taught you a portable architecture—the ability to build a brief, inward cloister wherever you stand.

Reflections Under High-Altitude Skies

Philosophy in Thin Air

At altitude, thought acquires a mineral clarity. Ideas precipitate out of the turbulence of ordinary life, becoming facets rather than fog. Perhaps it is the thinness of the air, or the labor of walking in Ladakh day after day; perhaps it is simply the humbling geometry of ridges against an oversized sky. Whatever the cause, the effect is consistent: the mind quiets, and what is essential steps forward. On a long traverse, a simple line of reasoning will keep company for hours. You play it like a string, check it against the rhythm of your breath, test its strength on an incline. Conclusions reached out here feel less like decisions and more like settlements, agreements made between attention and terrain.

There is a temptation to declare such reflection a luxury, the byproduct of free time in a decorated landscape. Yet the mountains argue otherwise. Reflection is a practical tool, a way to arrange priorities under conditions that make every kilogram count. Which plans are ballast, which are provisions? Which habits cost oxygen, and which give it back? High-altitude philosophy is small, precise, and sturdy. It prefers verbs to slogans. It asks: what can be done well, with care, today? And what can be left to the wind? On an evening ridge, when the sun combs light through a fringe of cloud and the valley darkens by degrees, the answers feel close. You write them down in your muscles and in the pace you choose tomorrow. In this sense, thought at altitude is not an escape from life; it is rehearsal for returning to it with a better instrument—one tuned to quiet, resilient notes.

Sometimes the path teaches in a language of breath and stone; you understand it first with your feet, and only later with your words.

The Art of Slow Travel

Slowness is often confused with delay, as if moving with care were a failure to arrive. A long walk in Ladakh corrects that illusion. Slowness here is not an accident; it is a technique. It allows a traveler to harvest details that speed would blur: the entomology of dust, the topography of shadow, the way a glacier’s memory lingers in the chill of morning air long after the ice has retreated. Slow travel is also an ethic. It asks you to take responsibility for your footprint, literal and otherwise, and to reciprocate the hospitality of a place with attention. That might mean choosing a local guesthouse over a large hotel, taking time to learn a few words of greeting, or returning an empty tea glass with the same care with which it was offered.

Practically, slowness is a design choice—an itinerary that favors fewer places, longer stays, and legs that connect by foot when possible. Philosophically, it is a recalibration of value. If the journey’s worth is measured only by the number of landmarks visited, the walker loses before leaving home. But if value is measured by depth—of encounter, of observation, of understanding—then walking in Ladakh becomes a generous account. Slowness reveals the economies of care embedded in the region: the way water is divided and shared, the rituals by which fields are set to rest, the seasonal calendars that make room for both labor and festival. Over time, the walker becomes a student of cadence—of how to move with a valley’s pulse rather than against it. Returning from such a trip, you discover that speed can be a useful tool, but slowness is a wisdom, and like most hard-won wisdoms, it does not shout.

Practical Notes for the Reflective Traveller

Best Time to Trek and How to Plan for Weather

The generous season for walking in Ladakh generally spans late spring to early autumn, with the most reliable windows often found between June and September. Yet dates alone do not guarantee conditions. Weather in the Himalayas is a negotiation between altitude, aspect, and wind. A north-facing slope can hold cold like a cellar while the next valley basks in a mild afternoon. Planning therefore begins with maps and ends with flexibility. Choose routes with escape options, build spare days into your schedule, and learn to read the sky as farmers do—attending to the behavior of clouds, the speed of the wind, and the quality of light at dawn. A traveler aiming for passes should expect colder nights and carry layers that can be modulated as temperatures swing. Sun protection is not optional. The sky is magnanimous with ultraviolet, and slowness in reapplying sunscreen is not philosophical, only careless.

Logistics should reflect the ethos of walking in Ladakh: thoughtful, light, considerate. Carry a reliable filter for water and spare the land the tyranny of plastic. Favor footwear with proven ankle support and break them in before you break yourself in. Trekking poles are more than accessories; they are persuasive negotiators during steep descents and river crossings. If your route crosses villages, coordinate lodging in advance with local guesthouses where possible, both for comfort and for the minor miracle of arriving to a hot kettle and conversation. Consider the moon. A full moon on a high plain can convert a night walk into a silver theater, but it will also steal warmth from the air. In short, plan with precision, travel with generosity, and let the weather be a teacher rather than an adversary.

Acclimatization, Health, and the Pace That Listens

Acclimatization is the art of introducing the body to altitude with care and courtesy. Begin modestly. Spend a couple of days in Leh or a lower valley before attempting higher routes, and treat those days not as delays but as training in attention. Walk, hydrate, and rest as if each were an equally essential verb. The signs of altitude stress—headache, nausea, dizziness, unusual fatigue—are not insults to your toughness but messages from a system adjusting. Listen early; the remedy is often a slower pace, a lower sleep, more water, and patience. When walking in Ladakh, consider adopting an itinerary that climbs in steps rather than leaps. If your day’s plan looks heroic on paper, it will feel bureaucratic in the lungs.

Food is fuel and also climate control. Daytime calls for frequent small snacks to prevent energy dips; evenings ask for warmth in a bowl—simple soups, rice, lentils. Tea is culture as much as hydration; accept it when offered and let it braid your day with local time. A compact kit should include blister care, a basic pain reliever, rehydration salts, and a layer that respects the suddenness with which sun can surrender to wind. Above all, match your ambition to your response. If the body requests a shorter day, that is an act of wisdom and not capitulation. The mountain will not be insulted by your discretion. Many walkers discover that the finest reflections occur on days when they chose to walk shorter, sit longer, and let the landscape come to them.

Permits, Paths, and Walking with Care for Place

Routes in Ladakh cross a mosaic of lands—village fields, communal pastures, protected zones, and sensitive border regions. Before setting out, confirm which sections require permits and how to obtain them through official channels or reputable local operators. These formalities are more than paperwork; they help manage fragile corridors where both culture and ecology are in delicate balance. On the ground, the ethic is simple: leave light traces. Keep to established footpaths when possible, avoid cutting switchbacks that prevent erosion, and treat cairns and chortens as the literature of the land rather than as props. When you share a trail with animals, yield with grace; their journey is not leisure but livelihood.

Waste is the traveler’s unsent letter—whatever you leave behind will be read by someone else. Pack it out. Consider the quiet economies you participate in when you stay, eat, and hire locally. Guides and porters hold encyclopedias of terrain knowledge, seasonal nuance, and story; their work is the connective tissue that keeps walking in Ladakh both safe and meaningful. If your route includes monasteries or sacred sites, follow local custom for dress and photography, and remember that silence is a language widely understood. Sustainable walking is not a marketing label but a series of small, persistent decisions. Each one says: I was here, and I tried to be a good guest.

FAQ

What is the best way to balance a reflective journey with practical trekking goals?

Begin by planning fewer locations with longer stays, and choose routes that can be walked rather than driven between. This structure frees hours for contemplation while keeping you honest about distance. Let practical goals—like reaching a pass—serve as frameworks, not tyrants, and allow weather, body, and conversation to revise your plan when needed.

How many days should I plan for acclimatization before longer routes?

For most travelers, two to three days at moderate altitude is a humane baseline before attempting higher trails. Use those days for short acclimatization walks, plenty of water, and attentive rest. If your body asks for more time, give it gladly; the mountain will still be there, and your walk will be better for the patience.

Can I experience cultural encounters respectfully without feeling intrusive?

Walk with an ethic of invitation. Greet first, linger only when welcomed, and accept tea as time offered, not as a transaction. Choose family-run guesthouses, ask before photographing people or private spaces, and let conversations travel at the pace set by your hosts. Respect is a tempo; match it.

Is slow travel feasible if I only have a week?

Yes—slowness is about depth, not duration. Focus on one or two valleys, reduce transfers, and design your days around walks of varying length with generous pauses for observation. A week can hold a surprising amount of clarity if you trade breadth for attention.

What gear most improves comfort on high-altitude walks without overpacking?

Prioritize layered clothing, reliable sun protection, a tested pair of boots, and a water treatment method you trust. Add trekking poles for joint care on descents and a compact kit for blisters and hydration. Everything else should audition for its place in your pack by proving its usefulness twice.

Conclusion

The Silence That Stays

Journeys end at an airport counter or a front door, yet certain landscapes refuse to release their hold. Ladakh’s contribution to memory is silence—persistent, articulate, generous. Days or months after returning, you will find it resurfacing while you wait in a queue or cross a rainy street. It arrives not as nostalgia but as a working tool, a reminder that attention is portable and that walking in Ladakh taught you how to carry it. The path becomes a grammar for ordinary hours: step, notice, breathe, repeat.

Clear Takeaways for the Reflective Walker

Move slower than your itinerary suggests and let the land rewrite your expectations. Treat acclimatization as a craft, not an obstacle. Seek valleys where hospitality is a form of architecture and monasteries where space is the first teacher. Pack light, walk kindly, and remember that the most durable souvenirs are habits—of patience, of listening, of care. These are the assets that continue to appreciate once you are home.

Afterword: A Note to Carry

Between Flags and Sky

There is a particular moment—somewhere between a line of prayer flags and an excess of sky—when you understand that you are not crossing a landscape so much as it is crossing you. The wind drafts your thoughts, the light edits your mood, and the ground underfoot introduces you to the oldest verb in the world: to walk. Keep a little of that verb in your pocket. Spend it often and without fear.

What You Bring Back

Bring back the discipline of looking twice, the courtesy of moving at a village pace, and the delight of finding philosophy in ordinary things: a kettle’s whistle, a roof’s shadow, a boy laughing as he outruns his own echo. If you must summarize the lesson, let it be brief and bright—walk as if the world is telling you something, because it is, and it always has been.

About the Author

Elena Marlowe is an Irish-born writer currently residing in a quiet village near Lake Bled, Slovenia. Her work weaves slow travel, high-altitude cultures, and the philosophy of walking into lyrical yet practical narratives for European readers.

Drawn to places where silence clarifies thought, she writes from footpaths and monastery courtyards across the Himalayas—especially Ladakh—exploring prayer flags, open skies, and the gentle art of moving lightly through rugged landscapes.

When not on the trail, she edits field notes by the lake, mapping routes, interviewing local artisans, and refining essays that balance reflection with useful detail—gear that earns its place in the pack, routes that respect altitude, and ways to travel with care.

Her columns are known for an elegant voice, attentive observation, and a measured pace that invites readers to look twice, walk slower, and carry the quiet home.