The Footpath That Runs the House

By Sidonie Morel

Morning, Before the Shops Fully Wake

The first circuit: latch, dust, water, return

In Leh the day often begins with a small walk that does not announce itself as anything special. A door latch lifts with a familiar resistance; the hinge answers in a dry squeak. In the lane, the ground holds yesterday’s dust in a fine layer that rises easily and settles again on socks and cuffs. A dog watches without moving. A broom scrapes somewhere behind a wall, steady and unhurried.

The route is short: a turn past shuttered storefronts, a few steps along a low wall, then the place where water can be taken. The handle of a container presses into the palm. Plastic, metal, rope—whatever it is that day, it has the same plain instruction: carry. The return is slower, not because the distance has changed, but because weight changes the shape of time. The air is thin enough to make pauses look sensible. People step aside without ceremony. Greetings are brief, often just a nod, because speech costs breath and breath is being spent on moving.

This is where “When Walking Becomes the Household: Ladakh as a Daily Path” begins in practice. The phrase is not an idea floated over the mountains. It is a routine with consequences: whether water arrives before the kettle, whether fuel is checked before wind rises, whether vegetables are bought before the sun turns the lane into glare. Walking is not a separate activity appended to life. It is the method by which life is assembled, one trip at a time.

Altitude as tempo, not drama

In Europe, altitude is often treated as an event: a viewpoint, a summit, a photograph. In Ladakh it is a tempo that settles into the body and stays there. The same lane that takes five minutes at sea level asks for a longer breath here. This is not hardship in the heroic sense; it is ordinary accounting. A person stops to adjust a scarf, to shift a load, to let someone pass. Nobody apologises for slowness. Nobody tries to win against the air.

These small pauses do something to observation. Details that would be skipped at speed become unavoidable: the grit that collects in a doorway, the thin shadow line under a window ledge, the poplar branches that move with a single-minded rustle even when everything else is still. If a phone stays in a pocket, the lane supplies its own noise: sandals scuffing, a distant kettle lid, a motorbike starting and then faltering, as if reconsidering whether the day needs it yet.

The early walk is also a kind of permission. It offers a simple freedom—moving without buying an experience, moving without being watched as a customer. The lane is not asking for admiration. It is asking for passage. The body answers by keeping going.

The Weight of Daily Necessities

Water makes the arithmetic visible

Carrying water in Ladakh teaches an uncomplicated mathematics. There is the weight itself, which is not metaphorical: it pulls on the shoulder, it presses into the fingers, it shifts the spine slightly forward. There is the surface underfoot, which decides how careful the return must be. And there is the distance, which is felt more as duration than as measurement. A person learns quickly that the shortest route is not always the easiest. A smoother lane may be longer but steadier. A shortcut may include a patch of loose gravel that turns a loaded step into a negotiation.

What changes, most noticeably, is thought. With hands full, thinking becomes narrower and more practical. The mind falls into single-file behind the body: step, balance, avoid, continue. This is not an uplifted state. It is a quiet sorting of priorities. A sentence that began in the head—an email to answer, a plan to refine—often breaks apart and returns later in a simpler form. The walk does not provide revelations on cue. It provides order.

European walking literature is full of grand pilgrimages and long-distance crossings, and those forms matter. But some of the most instructive pages are about what walking does to attention when it is not treated as a project. Here the jerrycan handle is the editor. It trims excess. It insists on what is real.

Errands as the spine of the day

The household in Ladakh is not maintained by a single sweep of effort but by repeated short movements: to buy vegetables when they are fresh enough, to check a gas cylinder before evening, to bring bread that will not crumble into dust by nightfall, to carry a message because signal fails in the wrong corners. Each errand is a thin thread. Together they make a rope.

The lanes reflect this repetition. Stones are polished at the edges where feet have passed. A low wall shows the darkened marks where containers have been rested for a moment. Near a shop entrance, the ground is slightly more compacted, as if it remembers queues that have formed there in winter. These are not decorative textures. They are marks of use, like the sheen on a wooden spoon.

It is easy, when visiting, to misread this as quaintness. But the rhythm is closer to maintenance than to charm. When walking becomes the household, it means the day is assembled through movement, and movement is shaped by what must be carried back. The romance, if any exists, is only in the fact that a system works.

Many Walks Inside One Place

Thresholds: guesthouse comfort to village reality

There is a particular kind of walk that happens in Ladakh without anyone naming it. It begins in a room with a curtain that blocks the morning glare, in a place where a visitor’s needs are anticipated: hot water arranged, slippers offered, a breakfast that arrives at a predictable hour. Then the door opens and the lane begins, and within minutes the atmosphere changes. The surface underfoot shifts. The air carries different smells—wood smoke, damp earth near a channel, frying oil from a small kitchen behind a wall.

This is not a moral lesson about authenticity. It is simply a change of context that walking makes immediate. You notice where not to stare. You notice how quickly you are identified as passing through. You notice the small infrastructures that hold everything together: a pipe running along a wall, a channel cut to guide meltwater, a stack of dried dung cakes arranged with the care of fuel.

Urban walking can teach a person to read a city’s seams—where the polished centre stops and the working edge begins. In Ladakh, that seam can be crossed in a short stroll. It is one of the reasons the “daily path” matters. It is not just a route; it is a line through different truths.

Devotional circuits: repetition as steadiness

Some paths are walked in a specific direction, at a specific pace, with an attention that is not showy. A stupa is circled clockwise. A mani wall is passed with a slight adjustment of body position, as if the feet know the correct distance to keep. People walk these circuits without fanfare. The point is not to be seen doing it; the point is to do it.

On such a path, sound changes. Voices drop. The scraping of a shoe on stone becomes audible. Prayer flags may be close enough to hear their fabric pull and snap. The route is often short, but repetition gives it weight. In a place where so much depends on weather and season, repetition offers a form of steadiness that does not require guarantees.

For a reader used to pilgrim routes mapped across Europe, it may be tempting to translate this into familiar categories. But the devotional walk in Ladakh is less a journey than a maintenance of relation—between a person and a site, between the day and a practice. Again, walking is not separate from living. It is one of the ways living holds its shape.

Edges and Orbits

The rim of town, where the postcard loosens

The centre of Leh has its own choreography: shops, cafes, travellers comparing itineraries, motorbikes cutting close. The edges are quieter, and for that reason, more revealing. Walking the rim is not a sightseeing strategy. It is simply where you find what a place requires in order to keep going: fields with their narrow irrigation channels, piles of building stone waiting to be used, stacks of firewood, repair work done in the open because light is free there.

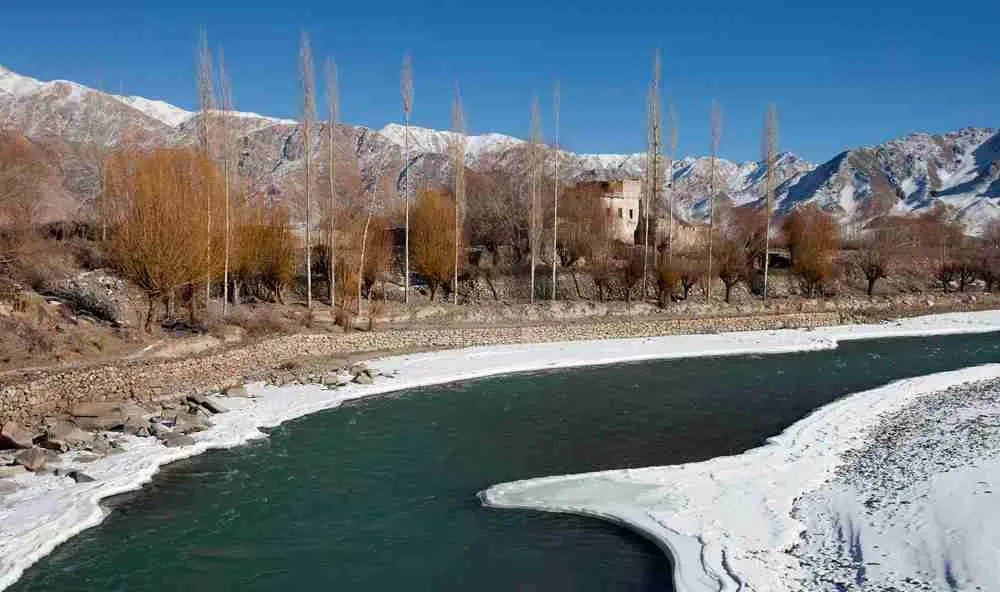

On the outskirts, the noise thins enough that you can hear water moving in a channel. You can hear a hammer on metal. You can hear the soft, persistent sound of feet on dust. The path may curve behind walls and open suddenly onto a line of poplars, their trunks pale against the ground. Dogs appear and disappear like minor officials, checking who is passing and why.

Walking literature that follows the boundary of a city often finds a different narrative there—less about monuments, more about systems and labour. Ladakh offers the same lesson in a compressed scale. The edge tells you what is stored, what is repaired, what is protected from wind. It also tells you what is discarded. A broken bucket. A torn sandal. The remains of packaging carried in from elsewhere. The household includes all of it.

Paths made by use, not by declaration

Some footpaths in Ladakh look like decisions made over decades. They cut across open ground where no pavement insists on direction. They follow the line that avoids a damp patch in spring or a drifted corner in winter. They are shaped by repetition and by the knowledge of small hazards: loose stones, sudden drops, places where dogs sleep, places where water runs unexpectedly after a thaw.

The most visible evidence of this is not a sign but the surface itself. A stone is worn smoother on one side. A step has been reinforced with an extra rock. A low wall has a notch where hands have rested while stepping over. These are modest forms of authorship. They are not dramatic enough for a brochure, but they make a place legible to anyone who walks it daily.

In an era where routes are often reduced to GPS lines and “must-see” lists, these paths offer a different kind of orientation. They are not invitations to consume. They are solutions to practical problems. Walking them teaches a visitor to follow rather than to claim.

Winter Without Romance

Ice, shadow, and the hour that matters

Winter changes the same lane into a different surface. A patch that was harmless dust in autumn becomes a slick glaze in shade. The sun arrives later and leaves earlier, and the time of day becomes a material condition rather than a preference. People choose routes with more light, not because they are prettier, but because warmth is safety. A longer path along a sunlit wall may be more sensible than a short cut through shadow.

Clothing becomes part of the walking system: layers that can be opened when exertion warms the chest, scarves that protect the throat from dry cold, gloves that allow fingers to keep working when they need to tie a strap or lift a latch. Breath is visible, not as poetry, but as an indicator. If it becomes too shallow, the body insists on slowing. If fingers become clumsy, the walk becomes cautious.

European narratives of winter walking sometimes lean into grandeur: snowfields, solitude, the aesthetic of endurance. Ladakh winter, in daily life, is more prosaic. It is the season in which walking becomes more obviously necessary and less easily described as leisure. The household still needs water, fuel, and food. The lane does not care what words you use for it.

Promises carried on foot

There are walks taken because someone is waiting. A message to deliver. A small favour. A visit to someone who has been ill. The walk is not framed as altruism; it is part of living among people who will, in another season, do the same for you.

Sometimes the only record of such a promise is the fact that someone arrives. The kettle is filled. Soup is made. A scarf is hung to dry. The walk does not become a story told loudly. It becomes a completed task, and the day moves on. In that sense, walking becomes the household not just through logistics but through social function. A community is partly maintained by the ability to show up, on foot, in the weather that exists.

What the Feet Teach the Sentence

Attention gathered by repetition

Some travel writing is built on the momentum of novelty: new landscapes, new foods, new strangers, new dangers. Ladakh, when lived through daily walking, offers a different engine. The same lane repeats. The same turn appears. The same wall holds its shadow. And yet the mind does not get bored in the way it expects, because repetition produces variation if a person pays attention.

One morning the dust is dry and lifts immediately; another morning it clumps, holding a hint of moisture. One day the wind arrives early; another day it keeps its distance until afternoon. A shopkeeper has a new bruise on his hand. A dog is missing for three days, then returns with a limp. A poplar line looks unchanged until the first leaves turn and the whole path seems to have shifted colour. These are not big events. They are the actual material of days.

This is also where the “daily path” connects to the wider tradition of walking as a way of thinking. Long walks have been used to clear the mind, to test an idea, to leave behind the noise of a city. But the most durable lessons often come from smaller distances walked repeatedly, where the world does not rearrange itself for the traveller. The traveller must become capable of seeing what is already there.

Evening: the return that closes without explanation

In the evening the lane is the same and not the same. Dust sits again at the threshold. Socks are loosened. A kettle is filled with whatever water has been carried back. The day’s purchases are set on a shelf. A door is latched with the same small resistance as in the morning.

Light changes quickly in Ladakh, especially in seasons when the sun drops behind ridges without a long farewell. A lantern may be switched on in a corridor. Footsteps fade into quieter parts of the house. Outside, prayer flags settle after wind, their fabric slack for a while as if resting.

Nothing needs to be explained at this point. The household has been run, largely by foot. The path has done its work. The next morning, it will do it again.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.