The Ancient Discovery That Revived a Lost Silk Road City

It began, as many stories do, with an accident. A hidden room, a broken latch, and a discovery that would reshape the life of a young boy caught between war and history.

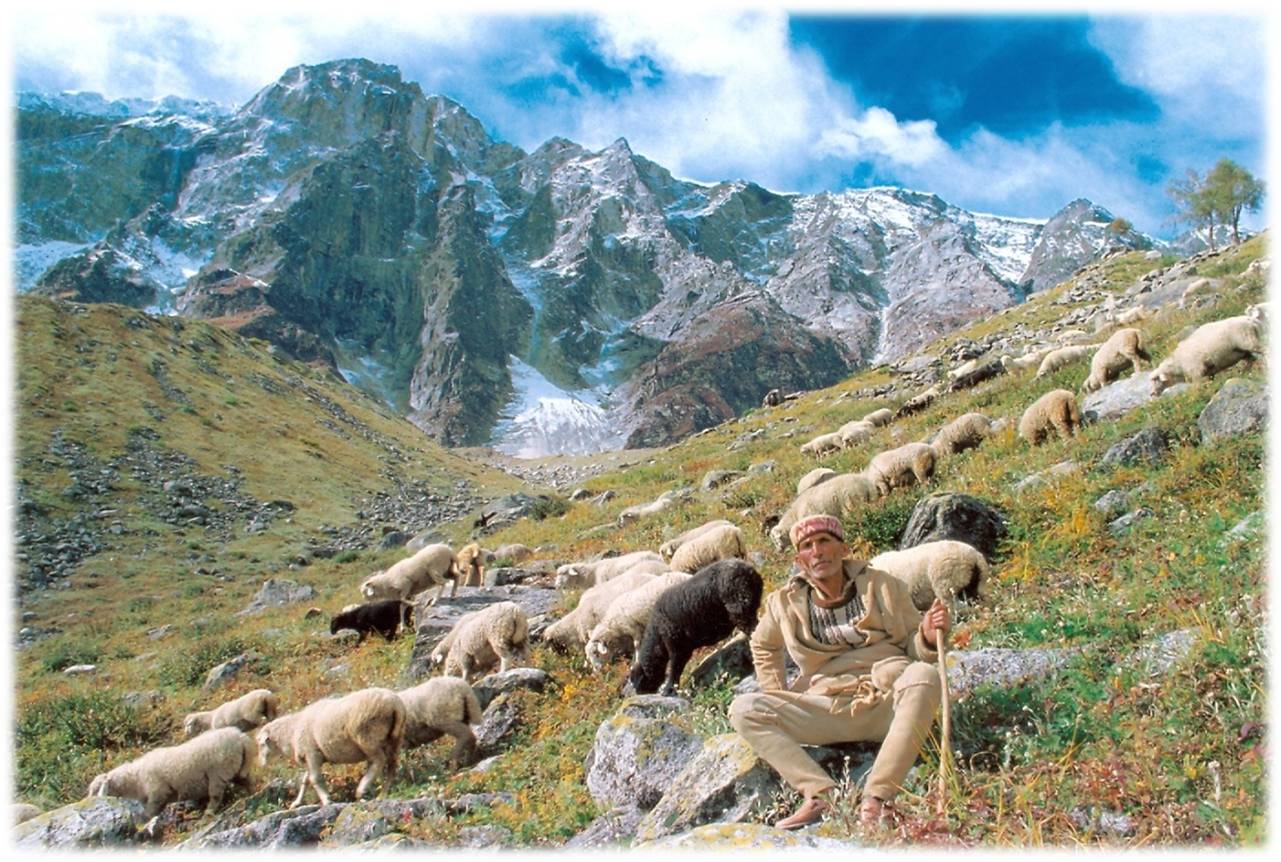

Faisal Rehman was just a child when the first bombs fell outside his schoolyard in Kargil, a rugged mountain city in Ladakh. It was 1999, and war had arrived in the form of distant artillery fire and the sound of fighter jets cutting through the sky. As the conflict between India and Pakistan consumed the region, his family fled south into the remote Suru Valley, seeking safety in a land of high peaks and silent glaciers.

Months later, when the war subsided and the displaced families returned, Rehman sat beside his bedridden grandfather, listening to a request that, at the time, seemed insignificant. The old man asked the family to check on an ancestral property near Kargil’s bazaar—an unremarkable, aging building first built by Rehman’s great-grandfather. No one expected what they would find behind its hand-carved wooden doors.

Inside, buried beneath decades of dust, lay wooden crates stamped with the names of cities from another era: Samarkand, Kashgar, Kabul, Isfahan. When the family pried them open, silks from China spilled onto the floor. They uncovered silver cookware from Afghanistan, Persian rugs, Tibetan turquoise, Mongolian saddles, and, surprisingly, luxury soaps and perfumes from London, New York, and Munich. What they had stumbled upon was not just a collection—it was an abandoned archive of the Silk Road, a time capsule of trade and empire.

That was 25 years ago.

Today, the Himalayan pass of Zoji La—once a perilous route for Silk Road traders and still one of the most dangerous roads in the world—remains a lifeline between Kashmir and Ladakh. I gripped the seat of my 4×4 as we climbed higher, the road crumbling at the edges, offering nothing but open air and a thousand-meter drop below. Across from me, Rehman sat in the front passenger seat, casually texting updates to one of his many ventures—a hotel, a museum, an NGO, a guided expedition service. This was just another commute for him, the same road his ancestors had braved for centuries.

I first met him in 2023, high in the frozen wilderness of eastern Ladakh, while searching for snow leopards. At 4,265 meters, in the midst of a swirling snowstorm, we sat drinking Kashmiri noon chai as he told me his story—one that began with war, led to the unearthing of a forgotten treasure, and ended in reconciliation.

The mountains of Ladakh have long been a crossroads of conquest and commerce, caught between the shifting borders of India, Pakistan, and China. Here, the Himalayas rise like sentinels, their glacial valleys sweeping into high plateaus where barley fields ripple like waves and white apricot blossoms cling to the Indus River’s edge. Snow leopards and Himalayan brown bears roam the ridgelines, moving like ghosts against the rock. And in the villages below, the people of Ladakh—Tibetan Buddhists, Muslims, and indigenous tribal communities—carry the echoes of those who came before them: traders, warriors, exiles.

And sometimes, when the dust is disturbed, history resurfaces.

The Lost Road That Still Leads to Kargil

The Silk Road. A name that conjures images of caravans snaking through desert landscapes, traders haggling in half-forgotten tongues, and the steady exchange of goods that stitched together entire civilizations. It was not a single road but a vast network, spanning 6,400 kilometers and linking Europe to the farthest edges of East Asia. The Romans coveted Chinese silk, and so the name stuck. But silk was only a fraction of what moved along these routes. Ideas traveled here. Religions. Currencies. A thousand secrets whispered from one empire to the next.

By 1453, the connection between Europe and China had been severed when the Ottomans turned their backs on the East. But trade does not simply vanish. In places like Ladakh, fragments of the ancient road remained intact, winding their way through the mountains, defying history itself.

A few days after our harrowing drive over Zoji La—the perilous Himalayan pass that has humbled even the most seasoned travelers—Faisal Rehman and I found ourselves at a quiet café in central Kargil. A simple meal of dal and masala chai, steam rising from our cups as the call to prayer echoed off the jagged peaks of the Zanskar Range. Somewhere nearby, the scent of wood smoke drifted from a bakery. It was here, in the quiet moments between conversation, that Rehman told me why his family had chosen to share the strange inheritance left behind by his great-grandfather.

The Silk Road’s Hidden Archive

For those wanting to experience Kargil’s Silk Road legacy firsthand, the journey itself is part of the story. The road from Leh or Srinagar follows the same ancient paths traders once walked, a route that remains as treacherous as it is breathtaking. Within Kargil, the Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum holds a collection of Silk Road artifacts—each item a clue to a forgotten world. Just beyond the town, 5th-century stone-carved Buddhas, sculpted in a Greco-Buddhist style, stand as silent reminders of the region’s historical ties to Central Asia and the Mediterranean.

For a deeper immersion, LIFE on the PLANET LADAKH offers a 10-day Silk Road expedition, tracing the old trade routes from Srinagar to Leh via Kargil and Zoji La. It is a journey through time, one that Rehman himself has retraced in his effort to understand his family’s past.

A Treasure Almost Lost

At first, no one in Rehman’s family knew what to do with the artifacts. The discovery had been overwhelming—a collection of silk, silver, copper, and rugs that had sat undisturbed for decades. Then, in 2002, word of the treasure reached anthropologists Dr. Jacqueline Fewkes and Nasir Khan from Florida Atlantic University. They traveled to Kargil, met with Rehman’s family, and understood instantly what was at stake. This was not just a collection. It was history itself, waiting to be told.

Under their guidance, the family took action. Rehman’s two uncles took charge—one as director, the other as curator—and in time, the Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum was born. Within its walls, visitors can now find relics of an age long gone: 18th-century Ladakhi bows carved from sheep horn, 19th-century Chinese copper water pipes, fragments of a world that once breathed in the cold mountain air of Ladakh.

But the true magic of the museum is not the artifacts themselves. It is the stories they carry.

“The Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum doesn’t have to, and should not, be the British Museum or the Smithsonian,” Dr. Fewkes told me. “Its value lies in the personal connections, the family narratives, the histories that would be lost in the grander national or international retellings of the past. Here, you see identity—not just trade, but the people who lived through it.”

The Past as a Road Forward

While his uncles manage the museum’s day-to-day operations, Rehman has taken a different path. His work is not just about preservation but about rediscovery. He is piecing together his family’s place in the Silk Road’s long and tangled history, uncovering connections that were nearly erased by time.

But beyond history, there is something else at stake. If Kargil’s past can be understood, perhaps its present can too. Perhaps, through the memory of trade, of movement, of exchange, a fractured community can find common ground.

For Rehman, the Silk Road is not simply a relic. It is a road still waiting to be walked.

A Forgotten Legacy and the Man Who Brought It Back

“It’s essential that people try to preserve their own family histories,” said Faisal Rehman’s uncle, Ajaz Munshi. “In this age of modernization, we are drifting further from our roots. If we don’t make an effort to keep our legacies intact, they will vanish.”

Rehman’s great-grandfather, Munshi Aziz Bhat, was born in Leh in 1866, a time when Ladakh was still deeply entwined with the currents of the Silk Road. After finishing school in Skardu—now part of Pakistan—he made his way to Kargil, then an important stop on the Treaty Road, a lesser-known artery of the old Silk Road that linked China to Central Asia via Kashmir.

“Kargil has always been connected to many parts of the world,” Rehman told me as we sipped chai in the dim light of his family’s museum. “Even its name means ‘a place to stop [between kingdoms].’”

Bhat had a keen sense for numbers, a skill that earned him a reputation as a shrewd accountant. But it was trade that ultimately defined his life. He started small, a single outpost in Kargil’s bazaar, but by 1920, that outpost had grown into something far greater: seven shops, an inn for weary travelers, and a stable for the camels, yaks, and horses that carried goods from places as distant as Lhasa and Yarkand. His hub became a lifeline for traders crossing the Himalayas, linking Central Asia, India, China, Europe, and even the Americas.

Rehman leaned back in his chair and smiled. “It’s fascinating to realize how globalized this region was back then. Kargil wasn’t just a stop on the map—it was cosmopolitan.”

The Last Trader of Kargil

But no trade route lasts forever. In 1948, the partition of India and Pakistan severed the ancient pathways that had once made Kargil a vital crossroads. Borders hardened. Trade collapsed. Caravans no longer arrived from the east or west. Munshi Aziz Bhat, one of the last merchants of the Silk Road, saw his life’s work come to an end. That same year, he locked the doors to his trade house for the final time. The keys were tucked away, and for nearly half a century, the rooms remained undisturbed, frozen in time.

The next morning, Rehman and I hiked along a ridge overlooking the Mushkoh Valley, a landscape still marked by the echoes of war. Scattered among the boulders were rings of stone and old sandbags, remnants of the 1999 Kargil War, a conflict that had redrawn the region’s reputation, branding it in the minds of outsiders as dangerous and war-torn.

“In Kargil, and in any place touched by war, people struggle with identity,” Rehman told me as we moved along the trail. “When your home becomes a battlefield, you start seeing yourself through the lens of conflict. It strips away your sense of pride. And that’s where I think tourism can help.”

Roots and Revival

Most travelers in Ladakh never venture beyond Leh, drawn to its Buddhist monasteries and elusive snow leopards. But Rehman has a different vision. He wants to invite people into Kargil’s past, to retrace the footsteps of Silk Road merchants, to stand in the old bazaar where traders once bartered over silks and spices. He wants visitors to see the echoes of a time when Kargil was not a place of conflict, but a place of connection.

“This is our home,” he said, looking out over the valley. “And I think it’s time people saw it for what it really is.”

A Legacy of Movement

“Our vision is to shift the perception of this place,” Faisal Rehman said, nudging the edge of a fresh snow leopard track with the toe of his boot. The print was still sharp in the mud, a perfect impression of the elusive predator that haunted these valleys. “People hear ‘Kargil’ and think of war. We want them to see something else. To see history. To see heritage.”

He paused, scanning the ridgeline. “I think a lot about my ancestors. About the people they must have met, the languages they must have spoken. Kargil was always a place of transit, a crossroads between worlds. It still is. And maybe, in my own way, I’m continuing that legacy—hosting travelers, welcoming guests, passing stories from one place to another.”

We followed the old Silk Road, winding our way up through Suru Valley toward the remote Buddhist kingdom of Zanskar. The road narrowed, carved into the mountainside, with only the ice-fed Suru River separating us from the glaciers above. As we rounded a bend, I saw them: three elderly women, walking beneath the shadow of a frozen tongue of ice, carrying enormous stacks of hay on their backs. They moved with the patience of those accustomed to distance, their homes still several steep kilometers away.

Rehman pulled over and offered them a ride. They hesitated at first, then, grateful, climbed into the back of the vehicle. One of them adjusted her shawl and turned to him.

“What news do you bring from the outside world?” she asked.

Rehman smiled, shifting in his seat. It was a scene that had played out for generations—travelers arriving from distant lands, stories exchanged over the crackling of a fire, goods traded in the dusty lanes of Kargil’s bazaar. Just as his great-grandparents had once done, he turned toward the group—this modern, multicultural band of travelers, weary from the road—and began to speak. Stories of politics and trade, of distant cities and changing times.

The road continued ahead of us, vanishing into the mountains. The Silk Road was gone, but its echoes remained.