Where the Stillness of Pangong Shapes the Traveler’s Imagination

By Declan P. O’Connor

1. Prologue: A Lake That Remembers Before You Arrive

The thin air, the long road from Tangtse, and the quiet threshold where stories begin

There is a particular point on the road beyond Tangtse where conversation fades without anyone agreeing to fall silent. The vehicle keeps moving, the engine still hums, but something in the air becomes so thin and insistent that words feel clumsy. The sky widens, the colours drain from the familiar spectrum of browns and blues into something more severe, and you realise you are no longer just going to a lake—you are entering a kind of listening chamber. Pangong Lake, for all its fame on social media and in glossy brochures, remains first and foremost a place of long echoes. The silence does not simply surround you; it presses gently against your ribs, asking if you are really ready to hear what it has to say.

For most European travellers, the journey up from Leh has already rearranged the internal map. Days of acclimatisation, slow climbs over high passes, cups of sweet tea taken in homestays and roadside cafés: all of it has been a rehearsal in slowing down. Yet the final approach to Pangong feels different. It is as if the previous kilometres belonged to the human world—villages, monasteries, checkpoints—while the last stretch towards the water belongs to the lake itself. Tangtse, that quiet town with its stream and stupas, is the last place where you feel history and geography balanced. Beyond it, the land appears to tilt towards something older and less negotiable. You are not only gaining altitude; you are moving into a corridor where your own thoughts will sound louder, stripped of background noise.

In that sense, the threshold to Pangong is not marked by a signboard or a dramatic bend in the road but by a shift in interior weather. Your mind, used to filling every gap with noise and planning, suddenly finds itself outpaced by the landscape. The lake is still out of sight, but its presence can be felt, like a memory waiting at the edge of consciousness, ready to be recognised when the blue finally appears.

How the high-altitude silence becomes a character in the narrative

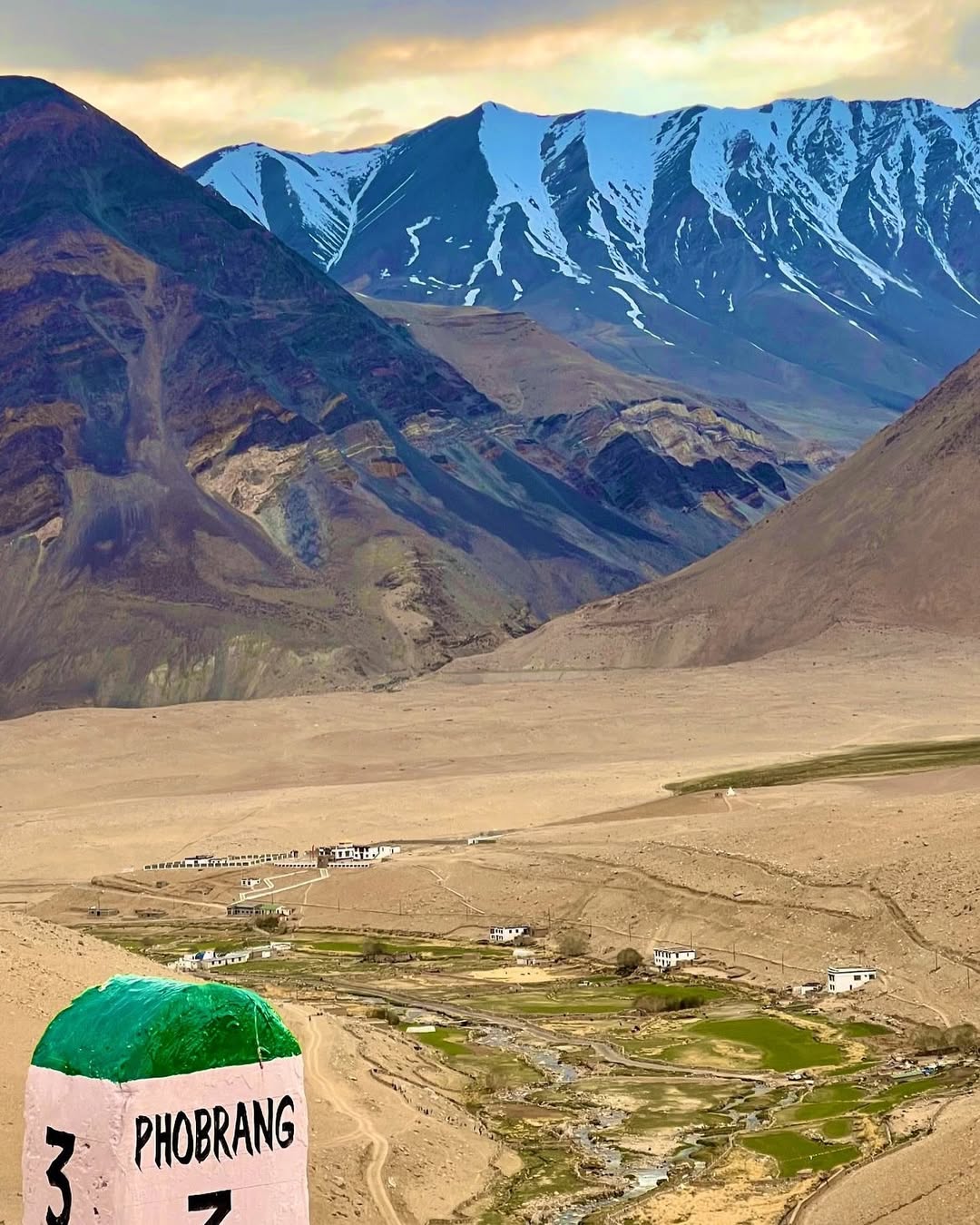

High-altitude silence is often mistaken for emptiness, a kind of blankness in which “nothing happens.” Yet in the villages around Pangong Lake—Spangmik, Man, Merak, Phobrang, Lukung, and Tangtse—that silence behaves more like a character than a backdrop. It has moods. It intervenes in conversations. It enlarges certain moments and erases others. You notice it first in the gaps between mundane sounds: a kettle boiling in a kitchen, a child chasing a dog across a courtyard, a distant truck grinding up the road. When those sounds fade, what remains is not absence but a presence that seems to lean in, attentive.

For the traveller who comes from dense European cities, where the hum of traffic and the glow of screens provide constant accompaniment, this can be disorienting. The stillness around Pangong is not simply a quieter version of what you know; it is a different order of experience. The lake’s surface can sit motionless for minutes, then suddenly respond to an invisible gust of wind, as though reacting to a question you did not know you had asked. In the same way, your thoughts slow, then surge, then fall back again. Stories you have told yourself about who you are and what you want to do with your life begin to sound different at 4,300 metres.

In these conditions, silence offers not an escape from narrative but a chance to hear it more clearly. You become aware of what you usually use noise to avoid confronting: uncertainty about work, unresolved conversations, anxieties that felt solid but suddenly appear negotiable. The villages around Pangong do not demand that you have answers. They simply refuse to distract you from the questions. The quiet becomes a companion, sometimes comforting, sometimes confrontational, always present. When you later remember your time here, you may recall the colour of the water and the taste of butter tea, but what will linger longest is the quality of the listening you were forced into—by the lake, by the altitude, and by the long hours in which there was nothing to do but pay attention.

2. The Geography of Quiet: Why These Six Villages Matter

A shoreline shaped by wind, time, and pastoral rhythms

Look at a map of Pangong Lake and you see a narrow, elongated strip of blue straddling a contested border. Look more closely, and the shoreline begins to reveal small indentations, valleys, and bends where human settlement has found a precarious foothold. Spangmik, Man, Merak, Phobrang, Lukung, Tangtse—each rests at a slightly different angle to the lake, to the wind, and to the patterns of pasture that have sustained life here for generations. Geography, in this part of Ladakh, is not a static backdrop; it is a series of negotiations between stone, water, animals, and people.

The lake itself behaves like a slow-moving mirror, changing its shade of blue or green depending on the hour and the weather. Villages on its shore sit like punctuation marks along a long sentence of water. Lukung, at the gateway, catches the first wave of visitors and returning traders. Spangmik, just beyond, becomes the place where most journeys turn into overnight stays, where tents and cottages dot the barren ground. Man and Merak, further along, are quieter clauses in that sentence, where the rhythm of life is dictated more by yaks, sheep, and school timetables than by arrival times of cars. Phobrang, slightly inland and closer to the routes that once mattered for trade and movement, feels like an ellipsis—suggesting other histories just out of sight. Tangtse, slightly away from the main shore but part of the same basin, offers a comma, a pause in the climb and a place to breathe.

These are not villages that have grown according to any urban plan. Their shape is dictated by access to water, shelter from the wind, and the availability of flat ground in a landscape that resists straight lines. Each place offers a different vantage point on the same body of water, and each, in turn, reflects back a slightly different story of how humans learn to live with altitude. Some travellers treat these stops as interchangeable—just names on an itinerary. But if you watch closely, you begin to see how the geography of each village creates its own tempo: when children play, when animals are moved to pasture, when smoke begins to rise from kitchen chimneys. The quiet is not uniform. It is as varied as the contours of the shore itself.

The subtle social world of Pangong’s eastern settlements

Although the landscape around Pangong often feels immense and sparsely populated, the social world of its villages is surprisingly intricate. Families are linked by marriages that cross from one settlement to another, by shared grazing rights, and by the practical realities of surviving long winters together. Conversations in kitchen-cafés and guesthouses often turn not to abstract politics or distant headlines but to water, fodder, schooling, and roads—the basic infrastructure that makes a future here imaginable for the next generation.

European visitors sometimes arrive with an image of the lake as a kind of high-altitude wilderness, untouched and isolated. But sit for an afternoon in a homestay in Man or Merak, and you begin to understand that these are not remote outposts forgotten by time. They are communities in motion, negotiating the pressures of tourism, military presence, climate shifts, and the aspirations of young people who scroll through the same global feeds as their peers in Berlin or Barcelona. A teenager might help her parents serve tea in the guesthouse, then later watch music videos on a phone whose signal depends on the mood of a distant tower and the weather.

In such a setting, hospitality is not a performance for visitors; it is part of a social code that extends inward as much as outward. A visitor accepted into a kitchen is expected to take part in the gentle choreography of conversation: answering simple questions about home, work, and family, then listening in return. Stories are exchanged alongside butter tea and momos, and the boundaries between guest and host become slightly blurred. In Spangmik and Lukung, where tourism is most visible, this dynamic is complicated by the constant flow of short-stay visitors, yet the underlying ethic remains. People watch how you move through their village, whether you greet elders, whether you step carefully around animals and children. In a world where the landscape appears vast and impersonal, the social fabric is intimate and finely attuned.

Eco-fragility, altitude ethics, and the responsibility of moving slowly

To travel along Pangong’s shore without considering the fragility of the ecosystem is to misread the entire landscape. The lake sits in a cold desert where water is both dominant and scarce, where a single broken pipeline or poorly conceived construction project can alter patterns of life more dramatically than an extra wave of tourists in any European capital. The soil is thin, the vegetation sparse, and the margin for error small. What looks like empty land is in fact finely calibrated grazing territory on which animals depend, and by extension, the households that rear them.

There is an emerging ethics of altitude that thoughtful travellers are beginning to adopt—one that recognises that every choice, from the number of nights spent in a single place to the kind of accommodation chosen, has consequences. Staying longer in one village rather than ticking off several in quick succession reduces the strain of constant turnover and offers hosts a more predictable rhythm. Choosing homestays or small guesthouses over large, resource-heavy camps can limit the ecological footprint. Walking short distances instead of insisting on being driven adds a layer of slowness that benefits both body and place. This is not about guilt but about alignment: allowing your behaviour to honour the constraints and gifts of the environment.

Altitude itself imposes another layer of responsibility. Moving too fast—to the lake, between villages, or through one’s own thoughts—can be hazardous. The thin air is indifferent to itineraries and ego. It demands humility: drinking water even when you are not thirsty, resting even when you are eager to see “one more viewpoint,” and listening to headaches or breathlessness as signals rather than inconveniences. For European travellers used to maximising weekend breaks and holidays, this can be a challenging adjustment. Yet it is precisely in embracing slower, more deliberate movement that the quiet stories of Pangong’s six villages become audible. The ethics of altitude is, in the end, an ethics of attention.

3. Spangmik: Where Most Journeys Touch the Water First

The ritual of arrival — tents, tea, and the first shock of blue

For many travellers, Spangmik is not just a village; it is the moment when the idea of Pangong Lake becomes a body of water at your feet. After hours of driving through rock and dust, the first sight of the lake’s intense blue feels almost theatrical. The road traces the shore, your driver perhaps teasing, “Just around this bend,” until the water suddenly appears—bigger, nearer, and more luminous than you had prepared yourself for. Spangmik stretches along this first accessible stretch, its tents and cottages dotting the shore like small exclamation marks of human presence against the long, horizontal line of the lake.

Arrival here follows a loose but recognisable ritual. You step out of the vehicle, slightly unsteady after the long ride, and the cold air hits your face. Someone from your chosen camp or homestay greets you, points you towards a simple room or tent, and offers tea. That first cup is rarely about flavour; it is a way of bridging the gap between motion and stillness, between the outside world and this narrow strip of land wedged between water and mountains. As you warm your hands around the cup, your eyes keep drifting back to the lake, as if you need to keep checking that it is still there.

Spangmik, with its concentration of accommodation options, can feel more “developed” than the other villages along the shore, but it also serves a crucial function. It acts as a decompression chamber where newly arrived travellers can adjust, physically and emotionally, to the lake’s presence. You see people reacting in different ways: some rush to take photographs, determined to capture every angle before the light changes; others sit quietly on a rock, letting the view soak in. Children run down to the water’s edge, shout into the wind, and run back laughing. The village absorbs all of this energy without losing its underlying rhythm: women carrying water, men checking on animals, children returning from school. The lake is spectacular, but life here cannot be paused for its sake.

Why Spangmik remains the emotional entry point for travelers

Spangmik occupies a curious place in the emotional geography of Pangong. Even travellers who later fall in love with calmer villages like Man or Merak often find that their most vivid memory is still that first evening in Spangmik. Part of this is simply the psychology of arrival; the first encounter with any powerful landscape tends to leave the deepest imprint. Yet there is more at work here than the novelty of the view. Spangmik is where expectations—fed by guidebooks, films, and social media—collide with reality in all its untidiness.

The village does not conform to the fantasy of untouched wilderness. There are generators humming in the background, solar panels leaning against stone walls, lines of laundry flapping in the wind. There are jeeps arriving and leaving, conversations about bookings, and occasional disputes over access or parking. For some visitors, this is disappointing; the Instagram image is contaminated by ordinary life. For others, it is quietly reassuring. The lake is no longer a backdrop to a carefully curated image. It is a place where people live, work, and negotiate the compromises of modernity at altitude.

For European travellers willing to stay longer than a single night, Spangmik can reveal a softer side. Early mornings, before most visitors have stepped out of their rooms, offer a glimpse of the village’s internal life: the sound of sweeping, the low murmur of radios, children getting ready for school. In late evenings, after dinner, the temperature drops quickly and conversations fragment into clusters around stoves. Stories about weather, animals, relatives working in distant cities, and the challenges of running a business here mingle with questions about your own life. It is in these exchanges that Spangmik ceases to be a “base camp for the lake” and becomes instead an emotional threshold—a place where the traveller’s story begins to intertwine with the lives of those who call the shore home.

4. Man: A Village That Hides in the Quiet Between Two Breaths

The stillness of mornings, the understated rhythm of daily life

Drive a little further along the shore from Spangmik and the noise thins out. The crowds recede, the number of accommodation signs diminishes, and the landscape begins to feel less curated for visitors. Man appears almost suddenly, a cluster of houses and fields set back from the water, as if the village had decided not to compete too directly with the lake’s drama. If Spangmik is the exclamation mark, Man is the pause between sentences—a place where stillness is not a spectacle but a daily condition.

Mornings here have a particular texture. The cold is sharp but bearable, made gentler by the smell of wood smoke and the sound of kettles boiling. Animals are led out to pasture with minimal fuss; children walk to school with a mixture of reluctance and excitement familiar in any village from the Alps to the Pyrenees. Yet the backdrop to these routines is unlike anything in Europe. The lake sits to one side, absorbing and reflecting the changing light. Mountains rise on all horizons, some to be ignored, others watched for incoming weather. The sky feels wider, the air more decisive.

Visitors who choose to stay in Man rather than simply pass through often do so for reasons they can only articulate later. They speak of needing a quieter relationship with the lake, of wanting to hear the sound of their own steps on the path without the constant presence of other travellers. In Man, the day’s rhythm is not organised around viewpoints but around chores. You find yourself adapting to this quieter tempo: waking with the light, moving slower, allowing the silence to stretch between conversations without the urge to fill it. The village does not perform slowness; it lives it. That difference is subtle but transformative for anyone paying attention.

How Man teaches the difference between solitude and loneliness

For travellers carrying unacknowledged exhaustion or restlessness, the quiet of Man can feel confronting. Without the distractions of a busier tourist hub, you are left with your own thoughts and the gently insistent presence of the lake. It is here that the difference between solitude and loneliness becomes more than a philosophical distinction. Solitude, in Man, is the freedom to sit on a low wall and watch shadows move across the water without having to explain yourself. Loneliness is what happens when you resist that freedom, when you try to replicate the stimulus of city life through screens or constant activity.

The village itself models a different approach. People here are used to stretches of apparent isolation—winter weeks when roads are uncertain, days when bad weather keeps everyone close to home. But they are rarely alone in the modern sense. Kinship networks, shared work, and a habit of dropping in unannounced to check on neighbours create a web of contact that does not depend on constant messaging. When a visitor stays long enough, they are gently drawn into this web. Someone may invite you for tea; a child may ask you to help with an English homework exercise; an elder may share a story about past winters or difficult years. Each of these small interactions chips away at the sense of being an outsider and replaces it with something more grounded.

For European travellers used to equating fullness of life with density—of events, appointments, or social engagements—Man offers a different metric. Here, a day in which “nothing happens” can feel oddly complete. You walked, you read, you watched clouds, you shared a meal, you slept. The village does not ask you to be more productive or more interesting. It asks only that you be present. In doing so, it provides a quiet answer to a question many of us carry: what remains of us when the noise stops?

5. Merak: Where the Lake Deepens Into Pastoral Memory

Yak herders, ancient trails, and the philosophy of slow movement

Further along the lake, beyond Man, lies Merak—a village that feels as though it has been listening to the same wind for centuries. If Spangmik is where visitors first touch the water and Man is where they learn to sit with silence, Merak is where they encounter a more pastoral, memory-rich version of life at the shore. Yak and sheep graze on sparse slopes, their movement slow and deliberate, guided by people whose knowledge of the terrain is both practical and intimate. Ancient trails thread the hillsides, linking seasonal pastures and neighbouring settlements, each path worn by repetition rather than design.

In Merak, the idea of “distance” becomes elastic. A walk that looks short on the horizon can take an hour at altitude; a day spent going to a nearby pasture and back feels full and complete. For those who live here, this pace is not a retreat from modernity but an adaptation to the realities of the land. For visitors, especially those arriving from European cities where speed is a virtue, this slower movement initially feels like an inconvenience. Why can the drive not be shorter, the path more direct, the phone signal more reliable? And yet, time spent in Merak has a way of turning these questions around. Instead of asking how to go faster, you begin to ask how much of the landscape you would miss if you did.

The philosophy of slow movement is not written down anywhere in Merak, but it is enacted every day. It is there in the way a herder chooses a path for the animals, taking into account not only the shortest route but the distribution of grass and the likelihood of sudden weather changes. It is there in the way people walk uphill: steady, measured, conserving breath. At night, when the generators stop and the sky floods with stars, the village’s relationship to time feels even more pronounced. You are not only at the edge of a lake; you are at the edge of your own accustomed speed.

Merak as a living archive of Changpa endurance

Merak is more than a pastoral postcard; it is a living archive of Changpa endurance and adaptation. While not all residents here identify as nomadic in the classical sense, the village is deeply connected to the wider Changthang cultural landscape, where mobility and resilience are central. Stories circulate about journeys undertaken in deep winter, about animals lost and found, about years when the snow came late or the grass dried too soon. These stories are not told as nostalgic laments but as data points in a collective memory, informing current decisions about grazing, migration, and livelihood.

For visitors, these narratives offer a corrective to romanticised images of “simple mountain life.” There is nothing simple about balancing household needs, children’s education, unpredictable weather, and limited cash economies at over 4,000 metres. Yet there is also a quiet refusal to frame life here only in terms of hardship. People laugh, argue, celebrate, and fall in love. They experiment with new crops, new building materials, and new opportunities provided by tourism, all while keeping one eye on the condition of animals and land.

European travellers who stay in Merak long enough to move beyond surface impressions often speak of feeling humbled. They see how much effort goes into tasks they usually outsource or mechanise—fetching water, maintaining paths, tending to animals. They notice how decisions are made collectively, how information travels through informal networks more efficiently than any official notice board. Merak does not present itself as a museum of tradition; it is a functioning, evolving community. To recognise it as such is to grant it the dignity of complexity, rather than reducing it to scenery. The village is, in that sense, an archive not only of endurance but of ingenuity.

6. Phobrang: A Settlement Near the Source of the Wind

The austere beauty of a non-touristic village

Leave the main tourist currents of Pangong and head towards Phobrang, and the landscape seems to shed even the remaining gestures towards comfort. The wind sharpens; the road feels more provisional. Phobrang is not a place of lakeside camps or curated viewpoints. It is a settlement that exists first for its own reasons—historic routes, grazing patterns, and administrative needs—and only secondarily for what travellers might seek. This difference is immediately felt. You arrive not as the main event but as a side note in the village’s ongoing story.

The beauty here is austere. There are no dramatic reflections of mountains in still water to frame through a camera lens. Instead, you find long views of open land, punctuated by low buildings and the occasional movement of animals. Colours tend towards a restrained palette of browns, greys, and muted greens, punctuated by prayer flags or painted doors. The wind seems to come from everywhere and nowhere, constantly rearranging dust and sound. For some travellers, this can be underwhelming. They have been conditioned to equate beauty with obvious spectacle, and Phobrang refuses to perform on those terms.

Yet to those willing to adjust their expectations, the village offers a different form of aesthetic satisfaction. You notice how a single beam of sunlight transforms a dull wall into something almost luminous. You watch two children invent a game with stones and a discarded tin, their laughter cutting cleanly through the wind. You observe the precise choreography of animals being led out and brought back in. The absence of overt tourist infrastructure means that your presence is less scripted; there is no standard set of activities to rush through. Instead, you are left with the raw material of place and time, and the responsibility to shape your own encounter with them.

Why its remoteness expands the emotional geography of Pangong

Phobrang’s remoteness is not only geographical; it is emotional. Coming here after spending time closer to the lake’s busier stretches is like stepping into the margins of a book. The main narrative continues elsewhere, but in the margins, you sometimes find the most revealing notes. The village’s distance from the tourist centres of Spangmik and Lukung allows the traveller to experience the Pangong region as more than a linear series of viewpoints. It becomes, instead, a wider emotional landscape in which solitude, uncertainty, and curiosity co-exist.

For European travellers used to strong itineraries and clear expectations, this shift can be transformative. In Phobrang, you cannot rely on a menu of pre-packaged experiences. You cannot assume that every question about logistics will have an immediate, polished answer. Plans are more vulnerable to weather, to the availability of vehicles, to the rhythms of local life. Rather than being a flaw, this vulnerability is part of the village’s teaching. It invites you to reconsider the assumption that travel must always be under your control.

This expanded emotional geography is not only about accepting inconvenience. It is also about discovering new forms of connection. A delayed departure might lead to an unplanned conversation with a family whose home you shelter in for an extra hour. A change in route may reveal a view you would never have included in a list of “top ten sights” but which sits in your memory long after you return home. Phobrang, in this sense, stretches the idea of what a trip to Pangong can be. It reminds you that some of the most meaningful places in a journey are those that offer less than you expected and more than you knew how to ask for.

7. Lukung: The Gate Where Water and Stone Negotiate the Light

A practical entry point, but also a metaphoric threshold

Lukung is often described in brief, utilitarian terms: the first village at Pangong, a checkpoint, a cluster of buildings where permits are verified and vehicles pause before continuing along the shore. Yet to see it only as a practical necessity is to miss the subtler role it plays in the experience of the lake. Lukung is a threshold, both literal and metaphoric. It is where the long, dry approach meets the first undeniable presence of water, and where travellers begin to renegotiate their relationship with distance, time, and light.

On arrival, your attention may be focused on formalities: documents, permissions, the questions of where to stay and for how long. But if you linger for a moment, you notice how the village is positioned at a kind of hinge point between the known and the unknown. Behind you lies the road from Leh, with its clear sequence of passes, towns, and familiar markers. Ahead lies a more ambiguous world of lakeside villages, restricted zones, and shifting stories about where one can and cannot go. Lukung manages this transition not with fanfare but with a kind of practical calm. People here are accustomed to the oscillation between busy days and quiet ones, between sudden rushes of vehicles and long stretches of stillness.

For the traveller, Lukung offers a chance to mark a psychological turn. You are no longer on the way to the lake; you are at the beginning of life with it. The air feels slightly colder, the wind carries a faint scent of water, and the light begins to behave differently, reflecting off surfaces in ways that complicate depth and distance. Standing on a small rise above the village, you can see both back along the road and forward along the shore, holding in one glance the journey you have made and the one still waiting.

How Lukung shapes the mental transition into the lake’s world

The significance of Lukung becomes clearer when you consider how it filters the traveller’s state of mind. Many arrive here tired, slightly altitude-worn, and eager to “see the lake” in a definitive way—one dramatic view, one perfect photograph. Lukung, with its modest houses, checkposts, and everyday routines, gently frustrates that desire for instant satisfaction. Before you can stand at the ideal vantage point, you must stand in queues, answer questions, and accept that you are entering a shared, regulated space rather than a private fantasy.

This delay is not merely bureaucratic; it has a subtle psychological effect. It introduces a small gap between expectation and fulfilment, forcing you to inhabit anticipation more consciously. In that gap, your imagination recalibrates. The lake is no longer just the endpoint of a list of sights in Ladakh; it becomes a place you are being granted conditional access to, with responsibilities attached. The mental transition from “I am going to see something beautiful” to “I am entering a fragile environment where people live and work” may not be fully articulated, but it begins here.

For European travellers sensitive to questions of sustainability and cultural respect, Lukung offers a quiet reminder that even the most remote destinations are enmeshed in systems of governance and negotiation. The permits, the checkpoints, the visible presence of the military—all these elements complicate any notion of the lake as a pure escape. Yet they also underscore the privilege of being allowed this far. To acknowledge that complexity is not to diminish the beauty of Pangong. It is to recognise that the lake’s quietest stories are inseparable from the realities that protect and constrain them, and that your role as a visitor is to listen within those constraints rather than imagine yourself outside them.

8. Tangtse: The Last Town Before Silence Becomes the Guide

A place of acclimatisation, monasteries, and quiet preparation

Tangtse sits slightly apart from the lake itself, yet it is impossible to speak of Pangong’s six villages without including it. If Lukung is the gate, Tangtse is the antechamber—a town where travellers, traders, and locals pause, prepare, and catch their breath before moving into the higher, more exposed world of the shore. Streets here are wider than in the small lakeside settlements, shops are more numerous, and there is a sense of modest bustle. Yet even in its busiest moments, Tangtse retains a softness, as though the surrounding mountains have wrapped the town in a protective curve.

For visitors ascending from Leh, Tangtse plays a crucial role in acclimatisation. It offers beds that are slightly lower in altitude than the lake, meals that are more varied, and, in some cases, the reassuring presence of a clinic. To spend a night here rather than racing straight to Pangong is not only a medical recommendation; it is a narrative one. It allows the mind and body to adjust, to gather themselves for the intensities of the lake. Monasteries in and around the town provide another layer of preparation—quiet spaces where the spiritual and the everyday coexist. Prayer flags flutter above roads where trucks rumble past, and the scent of incense drifts into courtyards where children play.

In the evenings, Tangtse feels like a place caught between two worlds. On one side lies the relative stability of the Leh road; on the other, the more uncertain terrain of the high-altitude frontier. Conversations in guesthouses and teashops often reflect this liminal position: half practical—about road conditions, fuel, and permits—and half reflective, as travellers confess their hopes and anxieties about the lake. For those who choose to listen, Tangtse is offering more than logistics. It is inviting you to consider what kind of encounter you want with Pangong: rushed or contemplative, extractive or attentive.

The cultural and logistical meaning of Tangtse as a waystation

Tangtse’s importance is not merely functional. Culturally, it serves as a meeting point between different livelihoods and trajectories. Traders, army personnel, civil servants, herders, and tourists all pass through, each carrying distinct stories and priorities. This convergence lends the town a subtle cosmopolitan feel, even as its physical scale remains small. In shops, you might see goods that have travelled across long distances, from India’s plains or even overseas, sitting alongside locally grown produce. In conversations, you hear a mix of local dialects, Hindi, and snippets of English exchanged with varying degrees of fluency and humour.

As a waystation, Tangtse shapes the ethics of movement towards the lake. Decisions made here—about how many nights to spend at altitude, which villages to visit, what kind of accommodation to choose—have consequences for both health and environment. Guides and drivers, often more experienced than their clients, use Tangtse as a place to gently argue for prudence: another night to acclimatise, more water, fewer “must-see” stops. For European travellers unaccustomed to such constraints, these conversations can feel like obstacles to spontaneity. Yet they are, in fact, part of a deeper choreography of care, honed over years of managing the meeting between fragile landscapes and eager visitors.

In this sense, Tangtse encapsulates one of the central tensions of modern travel: the desire to go further and faster versus the reality that some places demand slowness and respect. The town’s function as a logistical hub is inseparable from its role as a teacher of limits. Before silence and the lake become your primary guides, Tangtse gives you one last chance to align your expectations with the conditions ahead. To take that chance seriously is to honour not only your own well-being but the communities and ecosystems you are entering.

9. What These Six Villages Reveal When Seen Together

A chain of stories rather than a series of tourist stops

Viewed on an itinerary, the names Spangmik, Man, Merak, Phobrang, Lukung, and Tangtse can look like simple waypoints—a sequence of stops along a route to be checked off and photographed. Seen from within, however, they form a chain of stories, each village illuminating a different facet of life at the edge of this high-altitude lake. Spangmik shows what happens when spectacular landscapes meet concentrated tourism. Man offers a quieter, more domestic relationship with the water. Merak reveals the pastoral underpinnings without which no settlement here would be possible. Phobrang pulls the traveller into a more austere, less mediated environment. Lukung manages the threshold, and Tangtse frames the entire journey with its practical and cultural hospitality.

Taken together, these places challenge the notion that a destination can be captured in a single image or viewpoint. Pangong is not just “the lake” but an ensemble of human and non-human actors: animals, winds, roads, regulations, memories. Each village is a vantage point not only on the water but on the broader set of changes unfolding in Ladakh—climate shifts, economic pressures, educational aspirations. When a European traveller chooses to move through the region slowly, staying multiple nights, talking with residents, walking rather than constantly driving, the chain of stories begins to reveal patterns. You hear similar concerns voiced in different accents: about water, about winter, about the future of tourism, about children who may one day leave.

This narrative continuity does not erase the individuality of each village; it contextualises it. You begin to appreciate that what feels like a dramatic vista in one place is part of an everyday commute in another. You see how decisions made in Tangtse about infrastructure ripple down to Lukung and Spangmik, and how grazing policies affect Merak and Phobrang. The lake’s quietest stories are about these interdependencies—about the ways communities lean on each other, even when separated by long stretches of rough road. To witness this chain is to understand Pangong not as a remote escape, but as a living, connected world.

The ethics of attention: how listening changes the landscape

If there is a single thread that binds experiences across Pangong’s six villages, it is the practice of attention. Travel writing has long celebrated the idea of “seeing” new places, but here, seeing is rarely enough. The light is too sharp, the views too overwhelming, for sight alone to create understanding. What matters is how you listen—to the stories of villagers, to the needs of your own body at altitude, to the environmental warnings embedded in dry fields or receding snow lines.

Attention, in this context, is not passive. It has ethical implications. When you notice that water is carried in buckets rather than flowing from endless taps, your decision about how long to shower or how often to request hot water changes. When you hear the strain in a host’s voice as they talk about a shorter winter or a drier spring, you think differently about your own habits, both here and at home. When a driver suggests leaving earlier to avoid afternoon weather, you hear not just a preference but the echo of hard-won experience. Listening transforms the landscape from a backdrop to a relationship in which you are one, small but consequential, participant.

For European travellers accustomed to destinations marketed as playgrounds or escapes, this shift can be quietly radical. Pangong’s beauty remains astonishing; nothing in this ethical lens diminishes that. But it becomes impossible to see the lake and its villages as existing for you alone. Instead, you begin to understand your visit as a brief intersection of lives and paths, shaped by choices before and after your arrival. The ethics of attention does not ask you to fix anything—that would be presumptuous. It asks only that you remember what you learned here, and allow it to inform the stories you tell and the decisions you make once you descend back into thicker air.

10. Epilogue: Leaving Pangong, Carrying Its Stillness Home

The way high-altitude silence lingers in memory long after the journey ends

The drive away from Pangong is rarely as noisy as the drive towards it. The same bends in the road, the same stretches of stone and dust, feel altered by the knowledge that the lake is now behind you. In the rear-view mirror, if you are lucky, you catch one last glimpse of blue before the terrain folds in on itself and hides the water from sight. Yet the real separation happens more slowly, over days and weeks, as your body adjusts to lower altitudes and your mind starts to re-engage with emails, headlines, and routines. Somewhere in that transition, you realise that the silence you encountered at the shore has not stayed there. It has followed you.

High-altitude stillness leaves traces in unexpected places. You may find yourself standing at a busy European crossing, waiting for the light to change, and suddenly remembering the sound of wind moving across dry grass near Merak. You may sit in a crowded café and notice that, beneath the hum of conversation, there is a deeper quiet you can choose to listen to or ignore. Decisions that once felt urgent may look different when viewed through the lens of those slow days by the lake, when time seemed to stretch and narrow in ways that made productivity feel slightly absurd.

In practical terms, nothing may have changed. You still have deadlines, relationships, plans. Yet the memory of Pangong’s six villages introduces a new calibration. You know now what it feels like to live, even briefly, in a world where the horizon is wide, the nights dark, and the measure of a good day is not how much you accomplished but how present you were. The journey does not teach you to escape your life; it teaches you how to inhabit it more consciously. The lake’s quietest stories are not only about silence, but about the courage to listen to what silence reveals.

In the end, the gift of Pangong is not a photograph to be posted, but a question that keeps echoing long after you have left: What kind of life feels true when the noise finally fades?

FAQ: Traveling to Pangong’s Six Lakeside Villages

Is it safe for European travelers to visit the villages around Pangong Lake?

For most European travellers, visiting the villages around Pangong Lake is safe as long as you respect altitude guidelines and follow local regulations. The key risks here are not crime or social instability but environment and health: thin air, rapid weather changes, and limited medical facilities in some areas. If you acclimatise properly in Leh and, ideally, spend a night in Tangtse before going higher, you significantly reduce the likelihood of serious altitude sickness. Listening to your body—resting when tired, drinking plenty of water, avoiding heavy alcohol—matters more than bravado. In addition, keeping an eye on official advice about road conditions or temporary restrictions is important, since the region is geopolitically sensitive. When approached with humility and preparedness, the journey is not only safe but deeply rewarding.

How many nights should I plan to spend in the Pangong region to really experience these villages?

While one-night trips from Leh to the lake are common, they tend to compress the experience into a hurried sequence of views rather than a genuine encounter with village life. To feel the distinct character of Spangmik, Man, Merak, Phobrang, Lukung, and Tangtse, plan on at least three nights in the region, and more if your schedule allows. One itinerary might involve a night in Tangtse to acclimatise, followed by two or three nights divided between Spangmik and a quieter village like Man or Merak. Staying longer in fewer places generally yields a richer experience; you begin to recognise faces, rhythms, and small daily dramas. This slower approach also reduces the logistical strain on hosts and the environment, spreading your impact more gently across the days rather than concentrating it in a single, intense visit.

What kind of accommodation can I expect in these villages?

Accommodation around Pangong Lake ranges from simple homestays to more structured guesthouses and tented camps, with significant variation between villages. Spangmik and Lukung offer the broadest range, including seasonal camps with relatively comfortable beds and private bathrooms, as well as more modest lodgings. Man and Merak lean towards homestays or small guesthouses, where facilities may be basic but the depth of cultural exchange is often greater. Phobrang, with its less touristic profile, offers fewer options and may require prior arrangement through local contacts or guides. Everywhere, you should expect intermittent electricity, sometimes limited hot water, and nights that feel colder than you think your packing list covers. Rather than viewing these constraints as shortcomings, consider them part of the high-altitude experience: a chance to live closer to local realities and to appreciate comforts you might usually take for granted.

How can I travel responsibly and reduce my environmental impact in the Pangong area?

Responsible travel in the Pangong region begins with recognising that water, waste, and energy are all under pressure here. Bring a refillable bottle and use filtered or boiled water instead of buying multiple plastic bottles where possible. Avoid leaving any litter, including small items such as cigarette butts or food wrappers, which can linger in this fragile environment for years. Choose accommodations that demonstrate care in handling waste and water usage, even if their solutions are imperfect. Moving slowly—staying longer in fewer places, walking short distances instead of insisting on being driven—reduces fuel consumption and noise. At a more subtle level, responsible travel also means respecting local rhythms: asking before photographing people, dressing modestly, and listening to hosts’ guidance on where not to wander. Small gestures of consideration accumulate and help ensure that the villages you enjoy today remain viable homes for those who live there tomorrow.

What is the best season to visit Pangong’s villages for a balance of comfort and authenticity?

The most popular months to visit Pangong are from late May to September, when roads are open and temperatures, though still cold at night, are more manageable. During this period, you experience village life in its most active form: fields being tended, children going to school, animals moved regularly between pastures. July and August bring the warmest days but can also feel busier, especially in Spangmik and Lukung. Shoulder months—late May, early June, and late September—offer a quieter atmosphere and, often, a sense of the region on the cusp of seasonal change. Winter travel, while possible for the highly prepared, demands serious logistical support and is not advisable for most casual visitors. For European travellers seeking both comfort and authenticity, a shoulder-season stay with a few nights divided between a busier hub and a quieter village tends to provide the most balanced experience.

Conclusion: What the Lake Asks of Those Who Come

Clear takeaways for travelers who want to listen rather than merely look

To stand on the shore of Pangong Lake and watch the light move across its surface is to join a long lineage of watchers: herders gauging weather, children daydreaming, soldiers scanning horizons, travellers searching for words to match what they feel. The villages of Spangmik, Man, Merak, Phobrang, Lukung, and Tangtse create the human frame within which this watching becomes meaningful. They remind you that beauty, however absolute it appears, is always encountered from somewhere—from a courtyard, a roadside, a kitchen window. The lake does not ask you to be heroic or exceptional. It asks you to be attentive.

In practical terms, the takeaways are simple. Come slowly, allowing your body and mind to adjust. Stay longer in fewer villages, letting relationships and impressions deepen. Choose accommodations and behaviours that respect the scarcity of water and the effort it takes to create comfort at this altitude. Ask questions that show curiosity not only about scenery but about lives: schooling, winters, aspirations, worries. And when silence arrives—on a walk, over tea, or in the pause between questions—resist the urge to rush past it. That silence is not an absence of content; it is the medium through which the lake’s quietest stories travel.

For European travellers used to measuring journeys in terms of distance covered or lists completed, Pangong offers a gentler metric: how thoroughly you allowed a place to rearrange your sense of time, importance, and vulnerability. If you leave with fewer certainties and more nuanced questions, with a sharper awareness of your limits and a deeper gratitude for small comforts, then the lake has done its work. The stories you bring home will not be about conquering a landscape but about being changed by entering it carefully, listening more than speaking, and accepting that some of its meanings will remain, rightly, beyond your grasp.

Closing Note: Carrying a Piece of Quiet Back to Europe

An invitation to remember the altitude of your own life

When your plane descends towards a European city—lights in neat patterns, roads glowing, rivers tamed by embankments—it is tempting to file Pangong away as a beautiful exception, a high-altitude dream that belongs to a different world. Yet the quiet you met there does not have to stay pinned to that map. The memory of these six villages can act as a small internal altitude gain in your daily life, reminding you that time can be stretched, attention can be deepened, and not every available moment needs to be filled.

You may not have yaks outside your window or a lake changing colour with every hour, but you can choose, occasionally, to walk more slowly through your own streets, to sit without a phone in a familiar café, to listen more fully when someone tells you a story. The ethics of attention you practised at the shore—drinking more water than you thought you needed, resting when you were tired, respecting limits you could not negotiate—can be quietly repurposed for ordinary days. Pangong, in that sense, is not only a destination but a reference point, a reminder that another way of moving through the world is possible. You carry that possibility with you now, like a small, steady lake of stillness at the centre of your own busy map.

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.