After the Silk Route: Nubra’s Camels on Cold Sand

By Sidonie Morel

The first sight: dunes under snowlight

Hunder’s pale sand, Diskit’s shadow, and a camel that looks misplaced—until it doesn’t

In Nubra, the road drops and the air changes its weight. Leh’s dryness is still present—there is no sudden softness—but the valley loosens at the edges. You begin to see more poplar lines along fields, more willows near water, and then, unexpectedly, a stretch of pale sand where the wind has been patient for a long time.

Near Hunder, dunes lie low against the wider bowl of the valley. They are not tall, not cinematic in the way desert brochures promise, but they are precise: rippled surfaces that hold the day’s light and show you exactly where the wind has passed. In winter and early spring, snow can sit in the troughs like sifted flour. In summer, the same troughs hold a slightly darker shade, the sand compacted by the footfalls of people and the slow weight of animals.

A double-humped camel stands in that landscape with the calm of something that has done this work before. The body looks built for distances that require no romance. The coat—when it is thick—holds dust and loose fibres. The legs lift high and set down carefully, as if each step is being placed rather than thrown. The two humps are not decorative; they read like storage, like survival made visible. There is an oddness to the first encounter: a camel against a Himalayan sky, the wind carrying the faint mineral smell of a riverbed, a distant ridge still chalked with snow.

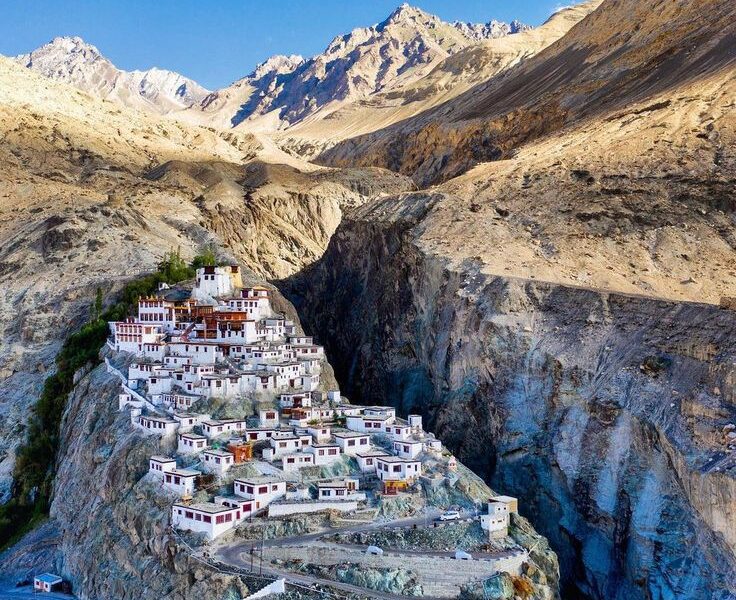

And then the feeling of mismatch fades. The dune field sits beside the Shyok River system; glacier-fed water runs cold and fast in its season, and the valley floor is broad enough for sand to collect where the river has rearranged itself over years. Diskit’s monastery is not far, perched on a slope, its lines holding steady while the valley below shows movement—fields, footpaths, the occasional military vehicle, a herd of goats being guided with minimal noise. The camel belongs to this mixture of stillness and passage. It is not a novelty so much as a clue.

Wind that tastes of glacier water, and the hush a valley learns from altitude

The air in Nubra is thin enough to make small actions noticeable. You register your own breathing when you climb the short rise of a dune. You notice the dryness in the mouth, the way a sip of water feels colder than expected. In the afternoon, the light can be sharp, but the temperature is not necessarily kind. Shade does not warm; it simply removes the sun. The wind arrives in brief, direct strokes, lifting sand grains that hit the ankle, then settle. Every surface collects a fine layer: the hem of trousers, the seams of a bag, the camel’s coat along the belly and the lower neck.

In a place like this, quiet is not a poetic decision—it is part of the terrain. Engines are rare enough that you hear them early. When there is a group of visitors, their voices travel farther than they expect, carried across a shallow bowl of sand and scrub. When a handler speaks to a camel, the sound is low and practical. Bells, if there are any, are small and sporadic: a brief metal note, then a pause, then another.

Often, the camel rides are framed as a postcard experience: “Sand dunes in Ladakh,” “The only Bactrian camels in India,” “Silk Route vibes.” Those phrases float above the scene and do not touch it. What touches it are simpler things: the steady pressure of a saddle strap; the way the camel shifts its weight before kneeling; the handler’s hands checking a knot without drama. The valley’s hush is not an absence; it is a space where small details become the story.

A valley made for passage

Nubra as a corridor: Leh to the north, the old road bending toward Central Asia

Nubra’s geography encourages movement. It is a meeting place of river valleys and high passes, with routes that lead north and northwest toward the Karakoram and beyond. Long before the modern road, this was part of a wider trans-Himalayan network that connected Ladakh with Central Asian markets—names like Yarkand and Kashgar still appear in accounts of trade that once felt routine, at least to those who lived by it.

Today, travellers come over Khardung La or the routes that skirt its idea—depending on road conditions, weather, and the season’s decisions. It can be tempting to treat the pass as a trophy: a sign, a photograph, a number. But the more interesting fact is that a pass is a filter. It limits what can be carried, who can travel, when they can travel, and how often. If you have to cross it repeatedly, year after year, the pass becomes a calendar as much as a place.

The valley opens after the climb, and its breadth suggests possibility. That impression is not new. Nubra has long been a practical corridor: for traders, for herders, for those moving between settlements and seasonal grazing, for pilgrims, for messengers. A corridor does not need a grand narrative; it needs reliability. It needs water at predictable points, shelter where possible, and the knowledge of people who understand what the weather does at certain hours. The old trade routes were built from that kind of knowledge, not from maps alone.

High passes, short summers, long memories—why routes here were never casual

The idea of a “Silk Route” can become decorative in European imagination—an elegant line across a map, a romance of textiles and spices. In Ladakh, the route is more physical. It is a track that becomes mud after an unexpected melt, a narrow section where a landslide has left gravel the size of fists, a stretch of road where the wind throws dust into the eyes and you keep driving because stopping does not help. Even now, the simplest rule remains: nothing is guaranteed.

This is one reason the double-humped camel makes sense. A Bactrian camel is not the camel of hot, soft deserts. It evolved for cold and for distance, for regions where fodder is sparse and the temperature drops sharply at night. It can handle dry air and rough ground. It can carry loads steadily over long hours. The animal is, in its own way, a response to the exact conditions that define Nubra: altitude, aridity, and the need to keep moving even when comfort is not part of the plan.

When a modern visitor sees a camel on sand, it can look like a staged scene. But if you widen the frame to include the pass behind you and the range ahead, the staging disappears. A route here is not a backdrop; it is a reason. And Nubra’s camels are not simply placed in the dunes—they are tethered to the valley’s history of passage.

When caravans were the heartbeat

What a caravan carried: wool, tea, salt, small metal goods, and the weight of distance

Caravans are easy to romanticise until you list what they carried. Goods were not abstract; they had weight and packaging and a cost to protect them from weather. Wool bales, tea bricks, salt, and small manufactured items moved along these corridors. There were also papers, obligations, relationships—trade is never only material. The work required planning in the ordinary sense: knowing where fodder could be found, how many days a stretch might take if the wind turned harsh, which valley might offer shelter if a route became blocked.

In such systems, animals were not ornaments. They were the engine, and each species had a logic. Horses could be faster but required certain care and feed. Yaks were powerful but tied to specific habitats and temperatures. The Bactrian camel offered a form of resilience: able to keep going with limited water, able to endure cold, able to carry substantial loads without rushing. Its wide feet manage sandy and stony ground. Its coat, when thick, is not decoration; it is insulation against nights that can bite even after a bright day.

There is a practical intimacy in caravan life: the sound of an animal breathing close to a tent wall; the moment a load shifts and has to be corrected; the way a handler checks a strap by touch, not by sight. Even if we can’t reconstruct every detail of caravans in Nubra with certainty from the dunes of today, the camel’s body still suggests what those days demanded. It does not carry the past as a metaphor. It carries it as a set of abilities.

The practical genius of the double-humped camel in cold, dry country

The two humps store fat; this is biology, not folklore. In harsh landscapes, fat storage becomes a way to survive scarcity. For travellers used to equating camels with heat, this can be a useful correction. The Bactrian camel belongs to cold deserts—regions where winter is real, where wind strips moisture from the skin, where fodder is not lush. Ladakh’s high-altitude desert fits that profile more than most first-time visitors expect.

In Nubra, the camel’s presence also maps an economic history. It tells you that this valley once sat in a chain of exchange that extended beyond current borders. The camel is evidence of connectivity, but not in the glossy sense. It is evidence of labour: the need to haul, to cross, to endure. It is also evidence of adaptation—how communities make use of what is available, how an imported animal becomes part of local work, how a landscape reshapes everything living within it.

Arrivals from the far side of the mountains

Yarkandi Bactrian camels and the long thread of the Silk Route

Accounts of Nubra’s Bactrian camels often trace their origin to trade with Central Asia, associated with Yarkand in the Tarim Basin. In many retellings, the animals were brought into Ladakh in the late nineteenth century as part of caravan trade, then remained because the route was alive. The detail matters not as a trivia point, but because it emphasises that Nubra’s camels are not an accidental curiosity. They are tied to a specific network of movement that once felt durable.

Over time, that durability changed. Borders hardened. Routes that had been commercial became political. By the mid-twentieth century, trade links that once brought caravans through Ladakh were curtailed or closed, and with them the economic logic of keeping large numbers of pack animals. In several narratives, this is the pivot: camels associated with caravan trade were left on the Ladakh side when cross-border movement ceased, and their population dwindled as their work disappeared.

The word “stranded” appears sometimes in discussions of these camels, and it is apt in a literal way. An animal built for long travel found itself in a valley where its historic route no longer continued. The story is not dramatic in the way modern headlines prefer. It is slow: fewer journeys, fewer needs, fewer hands willing to keep a costly animal with no obvious purpose. The camels remained, but the world that had required them did not.

Imported strength, borrowed survival: why these animals fit Nubra’s edge-of-the-world climate

It is worth being clear about what “fit” means here. Nubra is not gentle. It offers space, light, and dryness; it also offers cold nights, sparse grazing, and the kind of wind that turns lips into roughened skin. A Bactrian camel is not immune to these hardships, but it is equipped for them. That equipment—insulation, fat storage, endurance—makes the animal plausible in Ladakh in a way a one-humped dromedary would not be.

When you watch a camel being prepared for a ride, the practical needs are visible. Saddles are adjusted carefully; handlers check for rubbing points. In peak season, the work can become repetitive. The animal kneels, rises, kneels again. Its knees and joints take the burden of tourist rhythms rather than caravan rhythms, but the underlying mechanism is the same: this is an animal designed to carry, and the question becomes what, and at what cost.

The border closes, the story breaks

Mid-20th century shutdown: trade routes severed, caravans stopped mid-breath

In the middle decades of the twentieth century, shifts in politics and borders altered Ladakh’s trade environment fundamentally. Routes that once linked Leh and valleys like Nubra with Central Asian markets became restricted, and the caravan economy that depended on those movements declined. For a place whose history had been shaped by exchange, this was not a minor adjustment. It changed livelihoods and it changed what kinds of animals were worth keeping.

For Nubra’s Bactrian camels, this meant a loss of purpose in the strictest sense. Without long-distance freight work, an animal that eats and needs care becomes an expense. Numbers dropped. Stories from earlier decades describe a population reduced to a small remnant—kept, sometimes, because they were already there, because someone still saw value in them, or because letting them go entirely felt like losing a living piece of history.

It is tempting to tidy this story into a simple arc: trade ends, camels disappear, tourism arrives, camels return. Reality is more uneven. Some households kept a few animals. Some animals became semi-feral. There were periods of neglect and periods of renewed attention. When you meet a camel in Hunder today, you are not meeting a stable tradition. You are meeting a recovery that is also a reinvention.

Hunder after the caravans: the new trade

From freight to photographs: camel rides, dunes, and the economics of attention

The camel safari in Nubra is now a familiar image: a visitor seated high on a saddle, a short circuit across dunes, a phone held out at arm’s length. The ride is brief, and the scene is often framed to exclude everything modern: the parked vehicles, the stalls selling snacks, the generator sound from a nearby camp. It is easy to dismiss this as mere spectacle. It is also, for many families, income that arrives with the season.

This is the “afterlife of the Silk Route” in practical terms. A symbol of old trade is repurposed for new economies. The same animal that carried goods now carries tourists. The same valley that once hosted caravans now hosts photographers. The shift is not entirely cynical. It is one of the ways mountain regions survive: by converting what remains into something that can be traded again. But conversion always has friction.

One friction is the flattening of history into a single word: “Silk Road.” The phrase is useful for marketing because it compresses complexity into a familiar label. It also risks erasing what made these routes real—labour, weather, constraint. Watching a camel step through sand while the handler keeps pace beside it can return some of that reality. The handler’s job is not symbolic. It is work, measured in hours and seasons, in the condition of an animal’s knees and the steadiness of its temperament.

Who benefits, who labors, who watches—families, handlers, homestays, seasonal wages

Nubra’s tourism economy is not only camels. It is homestays, small hotels, drivers, cooks, guides, the sale of apricots and dried fruit, the rental of warm jackets, the simple logistics of getting fuel and food to a valley where the season is short. The camel ride sits within that wider system. Money exchanged on the dune field circulates through households in ways visitors do not always see.

At the same time, the concentration of activity in a few photogenic spots can create pressure. Animals work more when crowds are larger. Handlers may be tempted to stretch a day longer. Dunes can become congested in peak hours, and the experience becomes noisier, less controlled. The line between a sustainable livelihood and a stressed animal can be thin, especially in a climate where heat and cold are both sharp. If you want a small practical note embedded in the scene, it is this: go early, or go late. Give the place space. You will see more, and you will ask less of the animals.

Between care and spectacle

Animal welfare in thin air: workload, rest, and the everyday ethics of a ride

Ethics in travel often arrives as a lecture. In Nubra, it arrives as a question you can see. Is the camel standing quietly between rides, or is it being pushed to kneel and rise repeatedly with no pause? Is the saddle fitted properly, or does it rub against the coat and skin? Is the handler attentive to the animal’s pace, or impatient with it? These are not abstract concerns. They are visible on the ground, as plain as dust on a knee.

There are also conditions that are not visible but predictable. High altitude and dry air dehydrate bodies quickly. Temperature swings add stress. A camel built for harsh climates can still be exhausted by repetitive work and poor care. The most responsible places are often the least dramatic: fewer rides per animal, clearer rest periods, handlers who move calmly and do not treat the animal as a prop. Visitors can help by not bargaining aggressively, by choosing operators who seem to treat the animals with consistency, and by walking away if the scene feels like pressure.

Conservation as a word with sharp edges: genetic resource, breed survival, and real budgets

Beyond welfare, there is the matter of conservation. Nubra’s double-humped camels are sometimes described as a rare population, important as a genetic resource in India. That language can sound bureaucratic, but it points to something simple: once a small population shrinks too far, it becomes vulnerable to disease, inbreeding, and sudden shocks. Keeping a population viable is not only a matter of sentiment; it requires planning, veterinary support, and the kind of funding that rarely arrives neatly in remote valleys.

Tourism can help, by making the camels economically valuable again. It can also distort, by rewarding quantity over care. The tension sits inside the same scene: a camel kneeling on sand for a visitor’s photograph. It is both a livelihood and a risk. The most useful way to hold this tension is not to resolve it with a slogan, but to observe it honestly. The camel’s body is not a symbol; it is an animal that needs water, rest, and competent handling. Conservation begins there, not in the language around it.

A last image: evening on the sand

Diskit’s hillside fading, the river’s cold ribbon, and the camel turning homeward

In the late day, the dune field changes its colour. The pale sand takes on a slightly darker tone; the ridges sharpen as the sun drops. Shadows lengthen across the low bushes at the edge of the dunes. Diskit’s hillside becomes quieter, its buildings less distinct. The river—seen in parts rather than as a full sweep—holds a thin ribbon of reflected light.

A camel finishes a circuit and returns toward the tethering point with a slow certainty. The handler loosens a strap. The saddle is lifted and set aside. The animal shakes once, dust lifting briefly from its coat, then settling again. Nearby, a visitor checks a screen, perhaps pleased, perhaps disappointed, perhaps already thinking of the next stop. The scene is ordinary, and in that ordinariness the larger history is allowed to exist without being forced.

This is the afterlife of the Silk Route—not a costume, not a museum label, but a daily arrangement in a valley that has always dealt in movement. In Nubra, the old trade does not return in its original form. It returns as work shaped by a new economy, under the same dry wind, on the same ground that once held caravan footsteps. The sand keeps its record quietly, grain by grain, and the camel—built for distance—continues to do what it has always done: carry, endure, and move forward.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.