The Valleys Where Ordinary Days Carry the Weight of Centuries

By Declan P. O’Connor

Opening Reflection: Following the Indus Into Quieter Geographies

A river that reshapes your idea of distance and time

If you only meet Ladakh on the road between the airport and the cafes of Leh, the region can feel strangely compressed: a place of quick itineraries, checklists, and altitude statistics. Lower Sham, the quieter sweep of the Indus downstream from Leh, refuses that compression. Here the river widens, the light softens, and the distance between two villages is measured less in kilometers than in harvests, family histories, and the rhythm of irrigation channels opening and closing. The geography does something subtle to the traveler: it stretches your sense of time until an ordinary afternoon in a village lane begins to feel as deep as a week elsewhere.

Driving west from Leh, the mountains do not become less dramatic, but they become more familiar in their human scale. You see fewer hotel facades and more mud-brick walls patched by hand. Apricot trees lean into the road as if they were part of the traffic system. Small bridges cross the Indus at improbable angles, connecting not tourist “sights” but real lives: a primary school on one side, an orchard on the other, a shrine above. As you enter Lower Sham, you can feel yourself leaving the itinerary of the internet and re-entering something older, slower, and far more demanding of your attention.

The first temptation, of course, is to treat these villages as a charming backdrop for your own story: the European traveler who discovers “untouched Ladakh” and returns home with a string of photographs to prove it. Lower Sham is not interested in flattering that narrative. It asks a different question: are you willing to slow down enough to notice how much labor is hidden behind a single bowl of roasted barley, a single basket of apricots, a single courtyard swept before dawn? If you are, the region opens, not as a checklist of monasteries, but as a living corridor of villages along the Indus where Ladakhi life still breathes slowly, even as the outside world rushes past on the highway.

Why Lower Sham asks for a different kind of attention than Leh or Nubra

Like many visitors, you may arrive in Ladakh having already heard of the more dramatic regions: high-altitude deserts, famous passes, and valley names that show up on every trekking forum. Lower Sham rarely appears in the first line of those fantasies. It has no airport, no cluster of hip cafes where visitors can compare itineraries, and few of the quick visual rewards that a phone screen loves. That is precisely why it matters. This stretch of the Indus valley is not built to entertain you; it is built to carry water, store grain, shelter families, and hold a religious imagination that is older than your passport country itself. To move through it is to be a guest inside someone else’s working landscape, not the protagonist of a travel story.

In Leh or in the more photographed valleys, a traveler can maintain a kind of distance: you can admire the mountains from a rooftop, negotiate prices in a market, and then retreat behind a glass window. In Lower Sham, the boundary between observer and participant thins. Staying in a homestay in Alchi or Skurbuchan, you are never more than a few meters from someone’s kitchen fire or from a field that decides whether the year will be generous or tight. Conversation is not a performance for visitors; it is part of the ordinary fabric of the day. When a neighbor drops in for tea, you are sharing oxygen in the same story, whether you understand the language or not.

To appreciate Lower Sham, you need a different toolkit than the one you use for fast tourism. You need shoes that are comfortable at walking speed rather than summit speed, ears tuned more to water channels than to road traffic, and an imagination willing to be small in the presence of long-settled communities. This is a place where “offbeat Ladakh” does not mean an edgy secret for social media, but a slower form of hospitality that takes its time to decide how much of itself you are ready to see.

When the road becomes a soft border instead of a dividing line

The highway that threads through Lower Sham is, on any map, the main artery heading toward Kargil and beyond. Yet for the villages along the Indus, the road is not a hard frontier separating “local life” from “the world outside.” It is something more porous. Children walk across it to school; farmers drive their tractors along it in the early morning; monks hitch rides from one monastery to another when there is a ceremony or a funeral. Trucks carrying goods for distant markets share the tarmac with village buses, and once in a while with a tourist vehicle whose passengers are still adjusting their sunglasses after leaving Leh.

From the point of view of a visitor, the road offers choices. You can treat it as a conveyor belt, measuring your success by how quickly you move from one “must-see” to the next. Or you can treat it as a series of invitations, each side road and suspension bridge hinting at a slower world that the map does not detail. The turnoff to Alchi, the deviation to Mangyu, the entrance to Skurbuchan and Achinathang – each is less a detour than a test of whether you are willing to let the neat line of your itinerary fray a little in exchange for something more human.

If you take those turnoffs and cross those bridges, the geography of the journey changes. The Indus is no longer a river seen only from above through a car window; it becomes a presence you can hear at night from a homestay, a temperature you can feel in the early morning mist, a direction you unconsciously orient toward when you walk through fields. The road remains, but it loses its power as the dominant story of the landscape. In its place emerges a quieter map: paths trodden by generations between houses and fields, hidden stairs that connect monasteries to villages, and the thin lines of irrigation channels that make the difference between a green orchard and a dry slope.

The Character of Lower Sham: What Makes It Different From Upper Sham

Softer light, wider river, and the work of ordinary days

To understand Lower Sham, it is helpful to think of it not as a rival to the better-known upper valleys, but as a complementary note in a long piece of music. The upper Indus and high-side valleys often feel percussive: dramatic passes, sharp ridgelines, and thin air that forces every breath into your awareness. Lower Sham moves in a slower key. The river has settled into a wider bed, the mountains step back slightly from the water, and the villages spread out across gentler slopes. This does not mean the landscape is tame; it means that the drama is less about survival on the edge and more about the long-term negotiation between land, water, and labor.

In the softer light of late afternoon, you notice textures that might be invisible in harsher terrain: the exact way mud-brick walls catch shadows, the pattern of apricot branches framed against the sky, the deliberate geometry of terraces carved by generations who never once used the word “landscape.” Walking through a village lane in Lower Sham, you are surrounded by evidence that beauty here is not an extra layer applied after the work is done. It is the natural byproduct of work itself: a storage room stacked with hay in patterns that would not be out of place in a gallery, a courtyard broomed into clean circles, a row of drying apricots that looks suspiciously like intentional art.

This is also a region where rural life is not pitched as a spectacle for visitors. You can see the difference in how people respond to your presence. In some places increasingly shaped by tourism, the village street becomes a kind of stage. In Lower Sham, the rhythm of the day is set by tasks, not by arrivals. You are welcome to walk through that rhythm – to sit on a roof while someone threshes grain, to share tea while a neighbor repairs a wall – but you are not its center. For a European traveler used to being the assumed protagonist of the story, there is a quiet and necessary humility in that realization.

How isolation preserved an unhurried religious and agricultural culture

Lower Sham sits at a practical crossroads: it is on the road toward Kargil and yet still far enough from the main hubs of Ladakhi tourism that change has been slower. For centuries, its villages have balanced access and distance. Pilgrims and traders passed through, but most never stayed long enough to overwrite local customs. The monasteries in Alchi, Mangyu, and Domkhar became guardians not just of doctrine, but of a visual and architectural language that remembers Kashmir, Central Asia, and local Himalayan craft in the same breath. The fields around Skurbuchan, Achinathang, and Tia hold centuries of trial and error in how to coax grain and fruit from these altitudes with minimal water.

Isolation, in this context, has not meant purity in the romanticized sense, but continuity. The same irrigation channels that carry glacial meltwater to barley fields today were dug by ancestors whose names are no longer remembered but whose work remains the basis for every harvest. The small temples that dot the hillsides are not relics lying outside daily life; they are still used, still painted, still maintained, often by the same families who tend the orchards below. This overlap between spiritual and agricultural calendars is what gives Lower Sham its particular density of meaning. Festivals are not primarily performances for visitors; they are punctuation marks in a year whose main sentence is written in mud, seed, and water.

For travelers, this continuity presents both a gift and a responsibility. The gift is the chance to see a form of Himalayan life that is neither frozen in time nor entirely remade by outside demand. The responsibility is to recognize that even small actions – a photo taken without asking, a drone flown over a monastery, an impatient honk on a village road – can disrupt patterns that took decades to stabilize. To move through Lower Sham is to be reminded that culture is not a product stored behind glass, but a dynamic equilibrium constantly negotiated in kitchens, fields, and assembly halls.

Apricot orchards, mud-brick homes, and the architecture of resilience

It is easy to romanticize the mud-brick houses of Lower Sham. In the clear light, with a backdrop of mountains and a foreground of apricot trees, they lend themselves effortlessly to the camera lens. But if you stop long enough to look beyond the pleasing symmetry of whitewashed walls and wooden windows, you notice something else: these homes are highly evolved pieces of climate technology. Thick walls insulate against winter cold and summer heat. Roofs, often layered with earth and straw, double as drying platforms for apricots and vegetables. Internal courtyards collect light and shelter, turning limited space into a multi-use stage for daily tasks.

The orchards themselves are also devices of resilience. Apricots, barberries, and apples are not simply “local color”; they are savings accounts that bloom in orange and red. A good harvest can buffer a family against the uncertainties of grain yields or medical costs. During harvest season, you see this logic in motion. Every flat surface seems to hold a sheet of drying fruit. Ladders appear where there were none a week before. Children and grandparents share the same branch, one harvesting, the other passing baskets down. The entire village becomes a kind of open-air pantry, hedging against winter by banking sunlight in the flesh of fruit.

For a visitor, the temptation is to see these details as charming scenery, but they are better understood as a record of adaptation. Lower Sham lives within strict environmental limits: short growing seasons, limited water, and supply lines that can be interrupted by weather or politics. The villages along the Indus have survived not by pretending these limits do not exist, but by learning how to work within them with patience and craft. To walk through an orchard or sit inside a mud-brick house is to be inside a long argument with climate and geography – an argument that, for now, the villages are still managing to win, albeit narrowly.

Alchi: A Village Where Time Moves With Monks and Farmers Together

Walking through 11th-century walls that still smell of earth

The first time you step into the monastic complex at Alchi, the air itself feels different. It is not the thin, sharp cold of higher passes, but a denser, more layered atmosphere, carrying traces of oil lamps, old wood, and centuries of whispered prayers. The walls are low by Himalayan standards, their proportions closer to a human body than to a mountain. Inside, murals bloom in colors that have somehow survived a millennium of winters and monsoons, depicting deities, protectors, and intricate mandalas with a grace that feels almost fragile in the present light. As your eyes adjust, you realize you are standing inside one of the oldest surviving Buddhist temple complexes in Ladakh, yet the ground under your feet is still just earth, worn smooth by monks and villagers who never thought of the place as a museum.

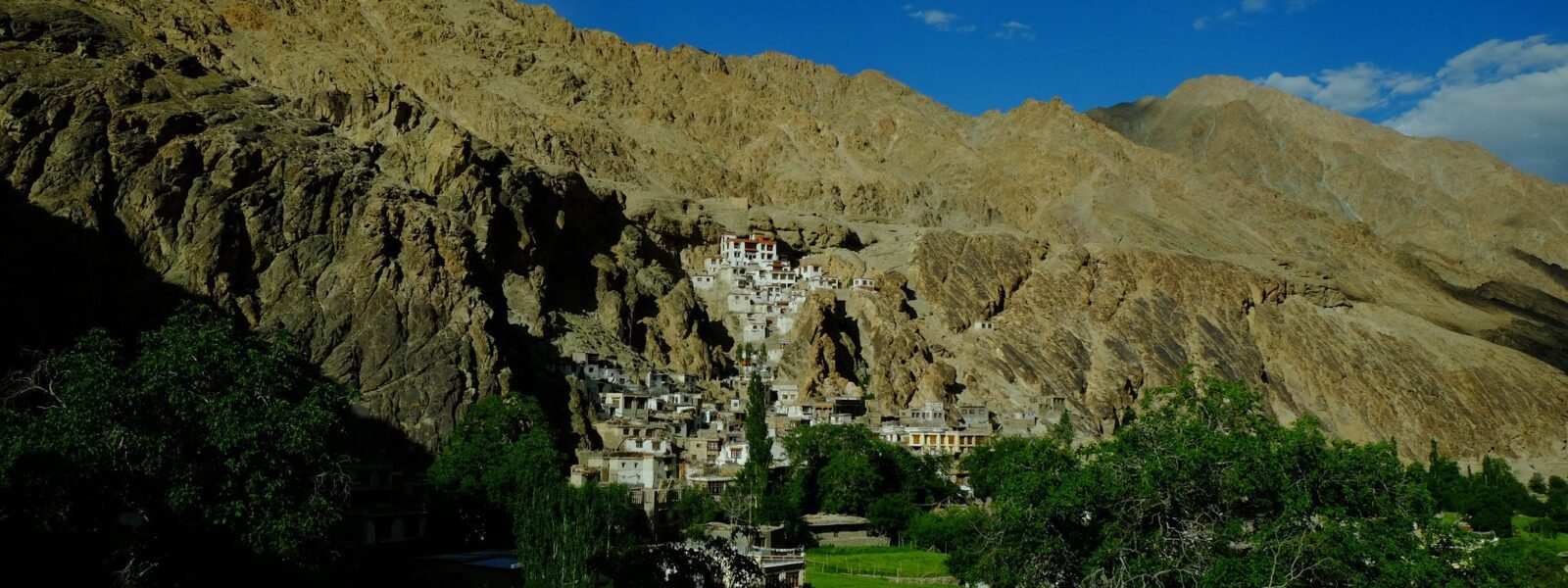

Outside, the village continues at its own pace. A path leads from the monastery down toward the Indus, passing homestays, small tea stalls, and orchards that have their own calendar, indifferent to the arrival time of tourist buses. Children chase each other around a chorten, ignoring the camera lenses pointed in their direction. A grandmother sits in a doorway spinning wool, half watching the visitors, half watching the sky. Alchi’s genius lies in this coexistence: the world-famous and the ordinary, the 11th-century mural and the 21st-century tractor, sharing the same narrow lanes without anxiety about their relative importance.

For travelers, the challenge is to resist the urge to isolate the monastery as the sole object of attention. If you visit only the painted walls and leave, you will have seen an extraordinary monument but missed the living context that keeps it from becoming a relic. To understand Alchi as part of Lower Sham, you need to stay long enough to see how the monastery fits into a wider ecology of fields, kitchens, and markets. You might have to accept that the most meaningful thing you do here is not photographing a famous deity, but helping your host carry buckets of water from a spring, or sitting on a roof at dusk watching the light withdraw from the Indus one field at a time.

Kashmiri brushstrokes, Himalayan dust, and the ethics of looking

Art historians will tell you that the murals in Alchi bear the imprint of Kashmiri and Central Asian styles, that they preserve a visual vocabulary which elsewhere has been largely erased by time, conflict, and neglect. They will talk about line quality, pigment, and iconography. All of that is true and important. But there is another, quieter truth that emerges when you actually stand in front of those walls as a temporary visitor from a continent far away: these paintings were not made for you. They were created for rituals, for local communities, for an understanding of the cosmos that preceded your arrival by centuries. To look at them today is to step into a conversation already in progress, not to open a book that was waiting on the shelf for you.

This recognition has consequences for how you move through the space. Instead of treating the murals as content to be captured, you might choose to treat them as presences to be greeted. You might linger in front of a single panel rather than trying to “see everything.” You might notice the ways in which the paintings have been touched, repaired, or even damaged by generations who understood them as part of daily religious life rather than as fragile artifacts. In a world where so much travel is framed as consumption, Alchi offers a radical alternative: encounter as a form of listening.

Lower Sham, through Alchi and its neighboring villages, teaches a particular ethics of looking. You begin to understand that the privilege of access – to ancient art, to village kitchens, to hidden courtyards – comes with the obligation to minimize harm. That might mean leaving your flash off, keeping your voice low, or accepting that certain inner spaces are not for you, no matter how photogenic they might be. It might also mean acknowledging that your presence, however respectful, adds to the pressure on a fragile site. The least you can do is move through that space with the kind of gratitude and restraint that remembers you are standing inside a story that will continue after you have gone.

Fields, homestays, and the slow conversation between visitors and villagers

A night in a homestay in Alchi is often an exercise in recalibrating expectations. You may arrive in the late afternoon imagining that the evening will revolve around you: your questions, your tiredness, your need for hot tea. Instead, you discover that your presence fits into an already full evening. Animals must be fed, a family member has to walk to the spring, dough needs to be kneaded, and someone is still finishing an errand in the fields. You are woven into this pattern, but the pattern is not rearranged around you. You sit at the kitchen hearth, watching as tasks move around you like planets around a sun that is not your ego.

As the hours pass, a conversation begins – sometimes in English, sometimes in fragments of Ladakhi and gestures, sometimes in silence punctuated by shared work. Stories emerge slowly: of harsh winters, good harvest years, relatives working in distant cities, memories of how the village changed when the road improved. You may be asked about your own life in return, not as a performance, but as a genuine curiosity. In that exchange, the categories of “host” and “guest” start to blur. You are not a client in a hospitality industry transaction; you are a temporary participant in a household’s attempt to sustain itself materially and culturally in a rapidly changing world.

For European travelers used to more transactional forms of tourism, this kind of stay can be quietly transformative. It asks you to accept a more modest role, to learn how to help without taking over, to enjoy comfort without demanding perfection, and to find meaning in the understated: the way a child falls asleep against a grandmother’s shoulder by the fire, the sound of the Indus in the distance, the smell of roasted barley filling a small room. Lower Sham does not announce these gifts loudly. It offers them to those who are willing to arrive not as conquerors of experience, but as students of ordinary days.

Saspol and Mangyu: Villages That Guard Their Stories Inside Caves and Courtyards

The painted caves of Saspol and the fragility of sacred images

Above the main village of Saspol, a dusty path climbs toward a cluster of caves cut into the rock. From the road below, they barely register as more than shadows, the kind of openings you might dismiss as empty. Up close, they reveal an entire hidden universe. Inside, the walls are covered with paintings – Bodhisattvas, mandalas, protective deities – executed with a fineness of line and a delicacy of color that feels almost impossible in such a harsh environment. Some figures are remarkably intact; others have been partially erased by time, weather, or human intervention. Together, they form a fragile archive of a religious imagination that once flowed freely across mountains and valleys.

Standing in the half-light of one of these caves, you are acutely aware of the vulnerability of what you are seeing. Unlike the more famous monastery rooms with controlled access, these paintings exist in a liminal space, literally and metaphorically. They are neither fully protected nor entirely abandoned. A careless touch, a dropped backpack, even the moisture from too many breaths in a small space could tip the balance. For the visitor, this creates a tension between the legitimate desire to witness something extraordinary and the recognition that your presence carries risk. To climb up, then, is to accept a responsibility: to behave as if your own child had painted these walls, and you wanted them to last another thousand years.

Saspol’s caves remind you that culture is not a fixed asset guaranteed by UNESCO designations or travel brochures. It survives through an ongoing negotiation between local communities, changing economies, and the occasional stranger who decides to climb a hill instead of staying in the valley. The least a traveler can do is honor that negotiation by moving gently, taking nothing, and leaving behind only the kind of memory that does no damage: a sharpened awareness of how tenuous beauty can be when it is exposed to the elements, both natural and human.

Mangyu’s secluded monastery and the silence that protects it

If Saspol’s caves feel like a whisper half overheard, Mangyu feels like a sentence spoken under the breath. Reached through a side road that pulls away from the main Indus valley, the village sits in a quieter fold of the mountains, its monastery tucked against a slope that seems to gather and focus the light. The temple complex here shares ancestral ties with Alchi; its murals and statues echo some of the same artistic lineages. Yet the atmosphere is different. Fewer visitors make it this far, and the resulting silence is not the silence of abandonment, but of concentration. You walk through courtyards where you can hear your own footsteps, through rooms where a single butter lamp still holds its small circle of flame.

The monks and villagers who care for Mangyu do so without the constant scrutiny of mass tourism. That can be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, the site is spared the daily wear of heavy foot traffic. On the other, it does not enjoy the same level of institutional support that higher-profile places receive. Maintenance becomes a local responsibility, carried out with limited resources and a deep sense of obligation. When you visit, you become, however briefly, part of that equation. The entrance fee you pay, the respect you show, and the stories you carry home all influence whether Mangyu remains a living center of practice or slowly fades into a footnote in guidebooks.

In a world that often equates value with visibility, Mangyu offers a counter-lesson. Here is a place whose importance is not measured by online reviews or visitor numbers, but by its role in the quiet continuity of belief and practice. To sit for a moment in its courtyard, listening to the wind move between prayer flags and walls, is to realize that some of the most meaningful sites in Ladakh will never trend. They do not need to. Their work is slower and more interior: holding a space where villagers can bring their fears, hopes, and grief, and where, once in a while, a traveler can learn that not everything worth visiting needs to be loudly advertised.

Why these villages offer a gentler form of pilgrimage for travelers

For many European visitors, the word “pilgrimage” carries religious or historical associations that feel distant from the idea of a holiday in the Himalayas. Yet walking the paths between Alchi, Saspol, and Mangyu, you begin to understand that pilgrimage here is less about doctrinal allegiance and more about a particular posture of mind. It is the willingness to let a place question your priorities rather than simply confirm your preferences. It is the decision to walk uphill to a cave or a temple not because it promises a spectacular view, but because it holds something fragile and important for the people who live nearby.

Lower Sham, especially in this cluster of villages, invites that gentler form of pilgrimage. Each visit, each homestay, each shared meal becomes a small act of recognition: these communities are not decorative extras on your journey; they are the main characters in their own ongoing story. Your presence is temporary, but it can be honorable if you allow it to be shaped by gratitude rather than entitlement. You are not asked to adopt a new faith or to perform rituals you do not understand. You are simply asked to walk with a bit more care, to listen with a bit more patience, and to remember that you are walking through neighborhoods of the sacred, even if you do not have the vocabulary to name everything you see.

In that sense, the slow villages of Lower Sham are among the best teachers a traveler can have. They do not lecture. They do not provide bullet-point lessons. Instead, they ask you to spend enough time in one place that the subtle details – the way a villager turns a prayer wheel before entering a room, the way fields are blessed at certain times of year, the way children learn to greet elders – begin to sink into your awareness. When you leave, you may find that the real pilgrimage was not to a specific temple after all, but to a different way of being present in the world.

The Agricultural Heartland: Skurbuchan, Achinathang, and Tia

Broad fields along the Indus and the choreography of work

Further downstream, the valley loosens a little, and the villages of Skurbuchan, Achinathang, and Tia spread themselves more generously across the slopes. From a distance, they appear as reefs of green anchored against a sea of stone – clusters of trees and terraces clinging to the cliff base and pushing out onto the river flats. Up close, you realize that what looked like a solid block of color is actually a sophisticated mosaic of different crops and microclimates. Barley here, wheat there, vegetables in a shaded corner, fruit trees wherever the soil is deep enough. Every patch reflects a long conversation between soil, water, and human beings who cannot afford to waste either.

During the growing season, these villages move with a pace that has nothing to do with tourist schedules. The choreography of work is intricate. At dawn, you might see men and women walking together toward the fields, tools over their shoulders, children trailing behind before they turn off toward school. Irrigation channels are opened and closed in an order optimized over generations. Someone climbs a tree to check whether the fruit is ready to dry; someone else bends over a vegetable patch, pulling out weeds that threaten the delicate balance between what is cultivated and what is merely opportunistic. In this setting, the phrase “rural life” stops being an abstraction and becomes a precise description of tasks, responsibilities, and mutual dependencies.

As a visitor, you have a choice. You can photograph the valley from the road and move on, satisfied that you have “seen” Skurbuchan or Achinathang. Or you can accept an invitation to stay in a homestay, to walk the narrow paths between fields, and to spend enough time that your memories are not just of scenery but of specific people. A farmer showing you how to tell if the barley is ready to harvest. A child offering you an apricot with the solemn pride of someone sharing the best thing they own. A group of women laughing as they work together, their conversation weaving through topics that you may not understand but can still feel as a form of shared strength. The geography of Lower Sham, here more than anywhere, insists that landscape and labor are inseparable.

Apricots as a currency of generosity and survival

If you arrive in Lower Sham during apricot season, you will quickly learn that the fruit is more than a snack. It is an axis around which much of village life turns. Skurbuchan and Achinathang, in particular, are famous for their orchards. Trees bend under the weight of orange fruit; the air carries a faint fermenting sweetness from the ones that have fallen to the ground. Everywhere you look, apricots are in motion: harvested into baskets, spread out on roofs and tarps to dry, sorted into piles destined for family use, for gifts, and for sale.

In economic terms, apricots are an important supplement to grain, a way of turning perishable abundance into something durable that can be traded or stored for winter. But on a human level, they also function as a kind of currency of generosity. It is difficult to leave a house without being offered at least a handful, often accompanied by a quiet insistence that you take more. The act of giving fruit is not a performance for tourists; villagers exchange apricots among themselves with equal ease. In a landscape where resources are finite and winters are serious, this willingness to share something so central to survival carries a meaning that goes beyond hospitality. It is a statement that scarcity has not yet managed to make people less open-handed.

For travelers used to supermarket abundance, the significance of this may take time to sink in. When food is always available, it is easy to forget that every calorie represents a chain of decisions and efforts. In Lower Sham, the chain is short and visible. You can look from the dried apricot in your hand to the tree it came from, the person who climbed that tree, the field below that feeds the family, the river that keeps the field alive. Accepting a small gift in such a context can feel disproportionate, almost embarrassing, if you are honest about the imbalance between your resources and those of your hosts. Yet refusing would miss the point. The appropriate response is not guilt, but gratitude deep enough to alter how you think about consumption when you return home.

Terraces, water channels, and the understated engineering of resilience

The terraces that sculpt the slopes around Tia and its neighboring villages are often admired for their aesthetic appeal, especially at sunrise or sunset when light and shadow emphasize their curves. But these structures are, first and foremost, pieces of engineering. Each terrace has been leveled and reinforced by hand. Each channel has been dug and maintained to carry just enough water – not too much, not too little – to keep crops alive in a region where rain alone is not a reliable ally. Over time, entire hillsides have been reconfigured to hold soil in place, slow water down, and create multiple layers of cultivation where once there may have been only scrub.

None of this is the work of a single visionary planner. It is the accumulated wisdom of countless decisions made by people whose names are not recorded, who learned from trial and error, who watched which parts of a slope held moisture longest and which crumbled under pressure. The result is a landscape that appears “natural” to an untrained eye but is, in fact, the visible surface of a complex system of knowledge. When climate scientists talk about adaptation and resilience, they would do well to spend time in these fields, listening to farmers explain how they decide when to sow, when to irrigate, and when to let a plot rest.

For a visitor walking along these terraces, the temptation is to step into the role of the contemplative observer, admiring the view and perhaps quoting a favorite line of poetry. There is nothing wrong with contemplation, but it can be enriched by attention to detail. Notice the subtle variations in terrace height, the stones placed at key points to guide water, the way certain plants are used to stabilize edges. Each of these choices represents a small act of intelligence, made without fanfare. In a century when so many societies are struggling to adjust to environmental change, the quiet competence of these villages is one of Lower Sham’s most valuable – and least advertised – teachings.

Domkhar and the Rock Art That Refuses to Disappear

What ancient petroglyphs whisper about early Ladakh

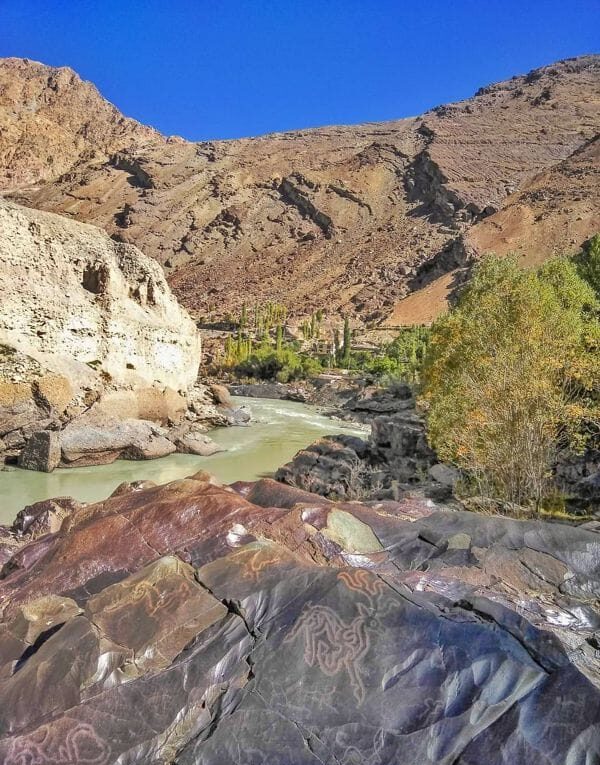

Near Domkhar, the rocks along the Indus carry marks that predate every monastery and many of the present-day settlements. At first, you might walk past them without noticing. The carvings are not monumental; they do not shout. But once someone points them out – a figure of a ibex here, a hunting scene there, abstract signs whose meaning has faded – you begin to see them everywhere, like a language whose script you suddenly recognize even if you cannot yet read it. These petroglyphs are among the oldest texts in Ladakh, written not on paper but on stone, composed not in sentences but in images.

Their exact meanings are a matter for specialists, but even a layperson can grasp some of what they imply. People have been here a very long time, watching animals, tracking seasons, investing particular places with significance. The Indus did not acquire its importance when modern states drew borders around it. It has been a corridor of movement and imagination for millennia. To run your hand lightly (and respectfully) over a carved surface is to bridge an almost unthinkable gap in time. You are touching the same rock that an unknown human being chose as their canvas centuries or even thousands of years ago. Your life and theirs intersect at exactly one point: the decision to pay attention to this place.

In an era obsessed with the new, Domkhar’s rock art offers the unsettling reminder that our presence in any landscape is temporary. Empires have risen and fallen since those carvings were made; languages have appeared and vanished; religions have been born, flourished, and declined. The ibex and hunters and symbols remain, weathered but legible, silent but eloquent. Lower Sham, through Domkhar, tells a long story in which the current generation – including the visitor with a digital camera – occupies only a brief paragraph. It is a humbling perspective, and a necessary one.

The archaeology of ordinary life in a living village

What makes Domkhar particularly interesting is that it is not an open-air museum sealed off from contemporary life. The village continues around and above the carvings. Children walk past them on their way to school, sometimes barely glancing at images that outsiders travel thousands of kilometers to see. Farmers graze animals nearby. Laundry hangs on lines where the wind also brushes against stones etched with ancient designs. This overlap can be jarring if you are used to heritage sites surrounded by fences and explanatory signage, but it is also honest. The past here is not a separate zone; it is folded into the present.

For travelers, this means that any visit to the rock art is also, inevitably, a visit to a community. You might stop to ask directions and end up being led by a schoolchild who has their own opinion about which carvings are most interesting. You might meet someone who remembers when a particular stone was partially buried and helped unearth it. You might notice the small ways in which the village negotiates the demands of preservation and daily life: a wall built just far enough from a carved rock to avoid damage, a shortcut path rerouted after someone pointed out that footsteps were wearing away a fragile surface.

This lived-in quality complicates any simple story about “saving the past.” Domkhar does not need foreign visitors to rescue its heritage, but it does benefit from respectful attention and support for local efforts to document and protect the carvings. Your role, as a guest, is not to arrive as a savior but as a witness willing to learn. If you can leave with a heightened sense of how deep the human timeline runs in this valley – and how easily it can be damaged by carelessness – then your time in Domkhar will have been well spent.

Why travelers should approach ancient art with humility

The longer you spend among Ladakh’s older sites, the more you realize that humility is not a moral accessory; it is a practical necessity. Ancient art, whether in the form of petroglyphs, painted caves, or monastery murals, is vulnerable not only because of age but because of the cumulative effect of thousands of small intrusions. A single touch may leave little mark. A thousand touches, over a few seasons of increased tourism, can alter a surface forever. In Domkhar, where the carvings are often out in the open, the margin for error is particularly thin.

This requires a shift in how travelers think about access. Instead of celebrating the ability to get “up close” to everything, we might begin to value the self-restraint that leaves a few layers of distance intact: a respectful space between hand and rock, a decision to refrain from carving one’s own initials alongside a Bronze Age ibex, a willingness to accept that some angles simply cannot be photographed without harm. Humility is also intellectual. We must be willing to admit that we do not fully understand what we are seeing, that our interpretations are partial and conditioned by our own cultural assumptions. The carvings in Domkhar do not need us to decode them in order to matter. They mattered long before we arrived and will continue to matter after we have moved on to the next destination.

In a wider sense, the humility learned at sites like Domkhar can spill over into how we move through all of Lower Sham. The same principle applies to village courtyards, fields, and kitchens. Not everything needs to be entered, photographed, or explained. Some things are best acknowledged from a respectful distance, with the understanding that being near is privilege enough. If we can learn to travel in this quieter key, we may find that our memories deepen even as our footprints grow lighter.

Khaltse and the Lives Built Around a Crossing Point

A town shaped by movement, not by spectacle

Khaltse rarely appears on dream itineraries. It is described, when mentioned at all, as a “junction town” or a “practical stop” on the way to more glamorous destinations. Yet to dismiss it as a mere waypoint is to miss a crucial piece of the Lower Sham mosaic. Khaltse is where the abstractions of geography – rivers, valleys, borders – become logistics. Trucks idle here, carrying goods between regions. Buses pause long enough for passengers to buy tea and snacks. Small shops, repair stalls, and eateries thrive on the pulse of traffic. The town has the slightly improvised feel of places that grew around necessity rather than grand design.

For the traveler passing through, the temptation is to see Khaltse only as a place to stretch one’s legs or refill a water bottle. But if you spend even a few hours walking its back streets, you begin to notice the layers beneath the surface. There are older houses tucked behind newer concrete facades, small shrines at street corners, and fields that start abruptly where the town ends. Children weave between vehicles with an ease that would horrify most European parents but is perfectly calibrated to the actual rhythm of local traffic. Khaltse may not be conventionally “beautiful,” but it is honest about the realities of life at a crossing point in the Himalayas.

In many ways, the town embodies the tension that runs through all of Lower Sham: between continuity and change, rootedness and movement. People here are accustomed to visitors, but not primarily of the touristic kind. Drivers, traders, soldiers, health workers – a constant stream of outsiders passes through, each leaving faint traces. The challenge for Khaltse, and for those who care about the future of Lower Sham, is to navigate this flow without allowing the town to become a mere service station whose only function is to accelerate someone else’s journey.

Markets, apricot trade, and the seasonal economy of the lower Indus

If you happen to be in Khaltse during peak apricot season, the town feels less like a junction and more like a crossroads festival. Crates of fruit appear in front of shops; families arrive from nearby villages with jeeps or tractors loaded high; bargaining takes place in a rapid-fire mix of Ladakhi, Hindi, and sometimes other regional languages. The apricot, which in villages like Skurbuchan and Achinathang feels deeply local, here reveals another dimension: it is part of a wider network of exchange that ties Lower Sham to markets far downstream.

Watching this seasonal economy at work, you gain a more nuanced understanding of how the villages along the Indus sustain themselves. Subsistence farming and local sharing are only part of the story. Cash is needed for school fees, medical expenses, fuel, and all the small necessities that cannot be produced at home. The sale of dried fruit, nuts, and other agricultural products becomes a crucial bridge between traditional livelihoods and modern obligations. Khaltse, with its shops and transport links, is a key node in this system. It might not be picturesque, but it is indispensable.

For travelers, respecting a place like Khaltse means recognizing that convenience is not a one-way gift. The tea you drink at a roadside stall, the bread you buy from a small bakery, the ride you negotiate to your next destination – all of these transactions exist within a larger web of labor and risk. Someone has to keep the road open, maintain the vehicles, stock the shelves, and absorb the shocks when weather or politics interrupt the flow of goods. To pause here with a little more attention, to greet people by name if you pass through more than once, to pay fairly and patiently, is to acknowledge that your ability to move easily through Lower Sham depends on the often invisible work of others.

Why the edges of a region often reveal its center

There is a peculiar paradox in travel: the places we consider peripheral often tell us more about a region than the sites we label as “must-see.” Khaltse, sitting as it does at the edge of what many visitors would recognize as “Ladakh proper,” is one such place. Here, you can observe the meeting of different worlds: mountain and plain, village and town, local routine and passing urgency. The conversations you overhear – about road conditions, prices, weather, family members working elsewhere – are not curated for outside consumption. They are the unfiltered soundtrack of a community negotiating its position in a wider, sometimes indifferent system.

In this sense, Khaltse is a kind of mirror held up to the traveler. It reflects back your own assumptions about what counts as “authentic” or “beautiful.” If you are willing to stay long enough to let the town’s pragmatic charm sink in, you may find that your definition of both words begins to shift. Authenticity starts to look less like a postcard-perfect village frozen in time and more like a place that has found ways to adapt without entirely losing its bearings. Beauty reveals itself in less obvious forms: a well-timed bus that spares a family a long walk, a shopkeeper who extends credit to someone short of cash, a group of teenagers navigating their future between inherited expectations and new possibilities.

By learning to see a junction town as part of the story rather than as empty space between attractions, you become a different kind of traveler. You start to understand that Lower Sham is not divided into zones of “culture” and zones of “logistics.” The monastery, the orchard, the rock art site, the bus stand, the mechanic’s workshop – all are pieces of the same intricate pattern. To appreciate that pattern fully, you have to be willing to look at its edges as carefully as its center.

What Lower Sham Teaches a Traveler Who Is Willing to Slow Down

Learning to let a landscape question your priorities

Lower Sham does not compete for your attention in the way more famous travel destinations do. It does not offer a long list of adrenaline activities or a skyline instantly recognizable from films and advertisements. Instead, it offers something more demanding and, in the long run, more valuable: the opportunity to allow a landscape and its people to ask you questions. What do you consider urgent? How do you measure a successful day? How much of your identity is built around movement, noise, and constant input? The villages along the Indus raise these questions gently but persistently, simply by going about their business in a rhythm that refuses to match your usual pace.

If you accept the invitation, you may find that your priorities begin to shift in ways that surprise you. Tasks that once felt essential – checking messages, posting updates, monitoring distant events – begin to loosen their grip when you are busy sweeping a courtyard, helping harvest a field, or simply sitting in companionable silence with your hosts. In their place, other values come into focus: being on time for shared meals, noticing changes in the weather, learning the names of people rather than just the names of places. Lower Sham does not demand that you abandon your previous life, but it does offer a temporary apprenticeship in an alternative way of being, one in which your worth is not measured by speed or productivity alone.

This apprenticeship is rarely dramatic. There are no formal ceremonies, no certificates to mark your progress. The learning happens in small increments: the first time you wake up before dawn without an alarm because your body has adjusted to the local rhythm; the moment you find yourself more interested in the story of a neighbor’s migration to a city than in anything happening online; the quiet satisfaction of realizing that you have, for once, paid full attention to an entire day without feeling the need to escape it. These are modest achievements by some standards, but they are exactly the kinds of achievements that a place like Lower Sham is uniquely qualified to nurture.

The ethics of moving slowly through fragile communities

Slowness is often sold to travelers as a lifestyle choice, an aesthetic: slow food, slow travel, slow living. In Lower Sham, slowness is less a brand than a necessity. Fields cannot be rushed. Water flows at the speed gravity dictates. Children grow according to their own timetable, not according to the deadlines of standardized curricula. For visitors, this reality carries ethical implications. To move slowly in such a context is not merely to consume a particular kind of experience; it is to align one’s behavior, however briefly, with the constraints and rhythms that shape local lives.

Practically, this might mean choosing to stay longer in fewer places rather than racing through a long list of villages. It might mean returning to the same homestay over several years, building a relationship that extends beyond a single transaction. It might mean asking before photographing, listening more than speaking, and being prepared to adapt your plans when a family obligation or local event temporarily reorders everything. The ethics of slow movement are not abstract ideals; they are visible in how you treat people who are not in a position to walk away from a negative interaction. A driver, a homestay host, a shopkeeper, a child – each encounter is a moment when you can either reinforce or gently resist the global habit of using places and people as disposable props in one’s personal story.

Lower Sham will not issue you with a moral checklist. It offers, instead, the clearer mirror of a context where the consequences of actions are harder to hide. If you behave badly, it will be noticed. If you behave well, the memory of that kindness will persist long after you have forgotten the details of your itinerary. The villages along the Indus have had to become experts in resilience, but they should not have to add “resilience to disrespectful visitors” to their skill set. Moving slowly, here, is one way of making sure they do not need to.

Why the Indus valley rewards attention more than ambition

Ambition is a powerful driver of travel planning. We want to see as much as possible, to stack experiences like trophies, to maximize the return on our investment of time and money. The Indus valley, especially in its quieter stretches, does not respond well to this mindset. It is not a theme park laid out for efficient consumption. The most meaningful encounters in Lower Sham are almost always disproportionate to the effort you can plan for them. They arrive sideways: a conversation on a bus, an unexpected invitation to a family gathering, a sudden opening in the clouds that bathes a village in evening light at precisely the moment you had given up on good weather.

Attention, rather than ambition, is the quality that allows these gifts to register. To practice attention in Lower Sham is to cultivate a readiness for the unscheduled. It is to notice the way the Indus changes color with the time of day, the way different villages structure their prayer routines, the way children adapt games to the contours of steep lanes and stone courtyards. It is to treat each day not as a container to be filled with planned highlights, but as a field in which you might find – if you look carefully – something small and unrepeatable that will stay with you long after the memory of mountain profiles has faded.

In this sense, Lower Sham is not just a destination but a training ground. If you can learn to travel attentively here, you will find that the skill translates elsewhere. You may begin to see your own home environment with new eyes, to recognize the quiet labor behind everyday conveniences, to value the small rituals that give shape to your own community. The Indus valley does not insist that you make these connections. It simply offers you the chance, in the form of a long, slow breath taken in a village where life still moves at a pace set by water, weather, and shared work.

Closing Reflection: The Landscapes That Stay With You After You Leave

Why memories of Lower Sham arrive later but last longer

There are journeys that dazzle you in the moment and fade quickly once you are home, their images sliding into the generic pool of mountains, temples, and sunsets it seems everyone has seen. Lower Sham tends to work in a different register. Many travelers report that their strongest memories from this region emerge not in the days immediately following their return, but weeks or months later, often triggered by something unrelated – the smell of wood smoke in winter, the sound of water in a quiet street, the sight of fruit drying in a neighbor’s garden. The villages along the Indus are not designed for spectacle, but they are rich in the kind of details that lodge quietly in the mind and resurface when you least expect them.

You might remember, with sudden clarity, the way the floor creaked in a homestay kitchen as your host moved between stove and storage room; the exact angle at which the afternoon sun entered a small shrine, catching the face of a statue that countless hands had polished smooth; the taste of tea made with water carried up from a spring you had walked past without noticing. These are not the moments most easily translated into stories for friends or posts for public consumption, but they are often the ones that continue to shape how you think about travel. Lower Sham becomes, over time, less a place you visited and more a lens through which you view other places, including your own.

In an age when travel is increasingly packaged as a series of instant impressions, the delayed impact of a region like this is quietly subversive. It suggests that the true measure of a journey is not how vividly it displays itself immediately afterward, but how persistently it influences your perceptions long-term. Lower Sham, with its quiet villages and patient river, has a way of slipping past your defenses and leaving a more permanent mark than many more dramatic destinations.

What European travelers often miss when they rush through Ladakh

European visitors to Ladakh are often constrained by time. Annual leave is finite, flights are long, and the pressure to “make the most” of a journey is real. Under those conditions, it is understandable that many itineraries focus on a rapid sequence of highlights: monasteries that appear on postcards, high passes with recordable altitudes, valleys whose names carry social capital. Lower Sham, if it appears at all, is frequently reduced to a quick stop at Alchi before pushing on toward other goals. In the process, a critical dimension of Ladakh is quietly edited out of the narrative.

What gets lost in that rush is not just a series of villages, but a particular experience of scale. Without Lower Sham, Ladakh can be misread as a region of extremes only – extreme altitude, extreme landscapes, extreme remoteness. The daily, sustainable middle – the zone where people actually live, farm, raise children, and age – fades into the background. When European travelers skip this layer, they risk carrying home an image of the Himalayas that is thrilling but distorted, foregrounding adventure at the expense of understanding. The mountains become a backdrop for personal achievement rather than a home for other people with their own complex, continuous lives.

Reintroducing Lower Sham into the story corrects that imbalance. It reminds travelers that Ladakh is not just a stage for their temporary presence but a set of intertwined communities with their own histories, challenges, and aspirations. To walk through a village lane here, to share a meal, to watch the careful work of tending fields, is to step briefly into that continuity. Even if your time is short, choosing to spend a portion of it in these quieter places can change the overall meaning of your journey in ways that no panoramic viewpoint ever could.

A single, simple sentence to carry home

If there is one line you might carry back with you from Lower Sham, it could be this: not everything important announces itself loudly. The Indus does not roar here; it moves with steady insistence. The monasteries are not always perched on dramatic cliffs; some are tucked into folds of the land where they might escape notice if you were not looking. The people who host you in their homes are not professional performers of hospitality; they are individuals balancing generosity with the demands of their own lives. The significance of these encounters is easy to underestimate while you are in the middle of them. Only later, perhaps, will you realize that they have subtly altered your sense of what matters.

In a world dominated by noise, speed, and spectacle, the quiet villages of Lower Sham along the Indus offer a different kind of education. They teach that attention is more powerful than ambition, that slowness can be a form of respect rather than a sign of failure, and that truly encountering another place requires the humility to accept that you are not the main character in its story. If you can remember even a fragment of that lesson when you return to your own streets and rivers, then the journey will have extended far beyond the days marked on your calendar.

In the end, Lower Sham does not ask you to conquer anything – not a peak, not a checklist, not a fear of silence. It asks only that you walk gently beside the Indus for a while, and listen.

FAQ: Practical Questions About Visiting Lower Sham

Is Lower Sham suitable for travelers who prefer slower, more reflective journeys?

Yes. Lower Sham is one of the best parts of Ladakh for travelers who value slow, reflective journeys over adrenaline-driven itineraries. The villages along the Indus are close enough to Leh to be accessible, yet far enough from the main tourist circuits to retain a quieter rhythm. You can stay in homestays, walk between fields and small monasteries, and spend time observing daily life rather than racing between “top sights.” For many European visitors, this balance between accessibility and authenticity makes Lower Sham an ideal place to experiment with a more attentive, less hurried approach to travel.

How many days should I spend in Lower Sham to experience it meaningfully?

If you only have a week in Ladakh, dedicating two or three nights to Lower Sham can already change the character of your entire trip. A single day trip to Alchi is better than nothing, but it rarely allows for the kind of unhurried encounters that make the region memorable. With several nights, you can stay in at least two different villages – perhaps one near Alchi or Saspol and another around Skurbuchan or Achinathang – giving you a sense of variety within the same valley. The longer you stay, the more the landscape and people shift from “background” to active participants in your story.

What is the best time of year to visit the Lower Sham villages?

For most travelers, the most rewarding months are from late May to early October, when roads are usually open and fields are alive with activity. In early summer, you see planting and the first flush of green; mid-summer brings fuller growth and long evenings; late summer and early autumn reveal orchards heavy with fruit and the intense energy of harvest. Each season offers a different angle on village life. Winter visits are possible for the well-prepared and well-supported, but they require more logistical planning and a tolerance for cold that many visitors underestimate. Whenever you go, it is wise to remember that this is an agricultural region; respecting local calendars can make your stay more harmonious.

Are homestays in Lower Sham comfortable enough for first-time visitors to Ladakh?

Homestays in Lower Sham are generally simple but welcoming, and they can be an excellent introduction to Ladakhi life for first-time visitors. You should not expect hotel-style amenities, but you can usually count on clean bedding, hearty meals, and hosts who take genuine pride in looking after their guests. Toilets may be traditional in some places, and electricity or hot water can be occasional rather than constant. For many travelers, accepting these conditions becomes part of the experience. If you approach homestays with flexibility and respect, you will likely find that the warmth of your hosts more than compensates for any lack of luxury.

How can I travel responsibly in Lower Sham without disrupting village life?

Responsible travel in Lower Sham begins with recognizing that you are entering communities shaped by limited resources and close-knit relationships. Ask before taking photographs, especially of individuals or inside private spaces. Buy what you can locally – snacks, fruit, small handicrafts – to support village economies. Keep noise levels low, particularly near monasteries and at night. Be patient with the pace of life; if a bus is late or a meal takes longer than you expected, remember that you are the visitor, not the benchmark. Above all, treat people with the same courtesy you would hope to receive if strangers appeared in your own neighborhood with cameras and backpacks.

Conclusion: Carrying the Lessons of Lower Sham Back Home

Clear takeaways from a quiet valley

If you strip away the romance and rhetoric, the lessons of Lower Sham are surprisingly concrete. First, a journey does not have to be dramatic to be transformative; villages along the Indus can change how you think about time, attention, and hospitality more effectively than any panoramic viewpoint. Second, the most meaningful cultural encounters often happen when you accept a supporting role in someone else’s story rather than insisting on center stage. Third, responsible travel is less about perfect ethics and more about a thousand small decisions made with awareness: where you stay, how fast you move, what you notice, and how you respond to what you see.

These takeaways are not confined to Ladakh. They can travel with you, quietly shaping how you move through other landscapes – urban or rural, near or far. You may find yourself more willing to talk with neighbors at home, more attentive to the invisible work that sustains your own community, more cautious about treating places and people as consumable experiences. In that way, Lower Sham continues to work on you long after you have departed, its river and villages still flowing through your choices in subtle but persistent ways.

A closing note for those still deciding whether to go

If you are reading this from a kitchen table in Europe, wondering whether the long journey to Ladakh is worth it, and whether Lower Sham deserves a place in a limited itinerary, the honest answer is simple: it depends on what you are hoping to find. If you seek only spectacle, there are many places on Earth to satisfy that craving more quickly and cheaply. But if you are curious about how people craft lives of dignity and meaning in demanding environments; if you sense that your own pace has become unsustainably frantic; if you are ready to let a quieter landscape ask you difficult questions – then the villages along the Indus in Lower Sham may be exactly where you need to spend a few unhurried days.

You will not return with a long list of records broken or extremes conquered. You may, however, return with something subtler and more durable: a renewed respect for ordinary days, a sharper awareness of the labor behind the food on your table, and a slightly revised answer to the question of what makes a journey worthwhile. In a world increasingly dominated by noise, speed, and spectacle, that might be the most valuable souvenir you can bring home.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh, a storytelling collective dedicated to the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life. His columns invite readers to move more slowly, listen more carefully, and meet Ladakh not as a backdrop for adventure, but as a living home for the people who shape its valleys every day.