An Afternoon in Leh, Measured in Stone and Blue

By Sidonie Morel

The Guesthouse Door and the First Honest Pace

Where the city begins: at a latch, at a scarf, at the throat

The guesthouse does not feel like a starting point until your hand is on the latch. Metal is always more sincere than a plan, especially in thin air. It tells you the truth: the morning warmth is gone, the afternoon brightness is already at work, and your fingers—European fingers used to gentler temperatures—need a second to understand where they are. I step out and the wide blue is immediate, as if the sky has lowered itself to inspect the roofs. Leh on foot begins like this, not with a grand intention, but with the body adjusting to the city’s clear insistence.

I wrap my scarf once, then again, and the gesture feels domestic, like tidying a room before guests arrive. Only the guest, here, is the wind. In Leh, even an afternoon can be dry enough to make your mouth feel like paper. The scarf softens that dryness; it also softens my own impatience. Leh on foot asks you to walk as if you mean it. If you hurry, the light turns arrogant. If you slow, the light becomes merely attentive. A courtyard somewhere is being swept; the broom’s rasp on stone is the first rhythm I trust. It is not a sound of tourism, but of living, the kind of sound you recognize in any country if you have ever lived long enough in one place to clean it.

On the lane outside, a dog lies in a square of sun with the composure of a true resident. A kettle argues quietly with heat behind a wall. A motorbike passes, then the street re-forms its older pace: not slow, not fast, simply human. I take a few steps and realize that my European habit of “covering distance” is going to be politely refused. Leh on foot does not reward conquest. It rewards noticing: the rough plaster that keeps last night’s cool, the smoothness of a stone worn by decades of soles, the way prayer flags can make color feel like a small act of defiance against so much beige and sky.

It is tempting to name the route immediately—market, old town, palace, Changspa Road, Shanti Stupa—but I prefer to let the day name itself. There is a practical pleasure in that choice. When you walk in Leh, your best map is not a line on paper; it is the body’s quiet arithmetic. Shade equals a pause. Thirst equals a turn toward tea. A tightening in the calf equals a gentler pace. Leh on foot makes these equations simple, and because they are simple, they feel elegant. I walk away from the guesthouse with nothing dramatic in mind, only the desire to spend the afternoon as one spends a good fabric: slowly enough to feel its weave.

Practical grace: the small habits that make the walk feel lighter

There are places where practicality has to be shouted, written in bold letters, repeated until a visitor obeys. Leh does not need that kind of instruction. Leh on foot teaches practicality by sensation. The sun does not “suggest” sunscreen; it makes your eyelids heavy with brightness until you understand, in your own way, that your skin is an instrument and must be treated kindly. The wind does not “advise” layers; it steps into the gap between shirt and collar and gives you a brief, sharp reminder that comfort is something you negotiate, not something you assume.

I have learned to keep my pace honest, and honesty is the most useful luxury on a Leh town walk. You will hear talk of altitude in numbers, but the body understands it as a different tempo. You speak in shorter phrases; you climb with less vanity; you accept pauses without embarrassment. I notice this in myself: I stop to watch a woman fold cloth in a doorway, not because I am romantic, but because the pause feels correct. Then I move again, and the movement feels correct too. Leh on foot is full of these small corrections, like adjusting a cuff or smoothing a sleeve.

European readers sometimes want a clean sequence: first this, then that, and a neat reward at the end. In Leh, the reward is often a minor comfort arriving at the right moment. A stretch of shade appears just as your shoulders begin to tense. A small shop front offers water when your mouth starts to feel chalky. An apricot smell drifts from somewhere and makes you realize you are hungry in the slow, civilized way, not the rushed way. These are not dramatic events, but they change the quality of the afternoon.

So I carry only what keeps the walk simple: a bottle of water, a few notes folded in the pocket where they will not crumble, and a willingness to stop without guilt. Leh on foot asks you to be practical in the same way it asks you to be elegant: by choosing what is necessary and leaving the rest behind. As the street grows busier and the soundscape thickens—voices, shutters, the thin ring of metal against metal—I know I am drifting toward the market, not because I chased it, but because the city’s pulse has begun to guide my feet.

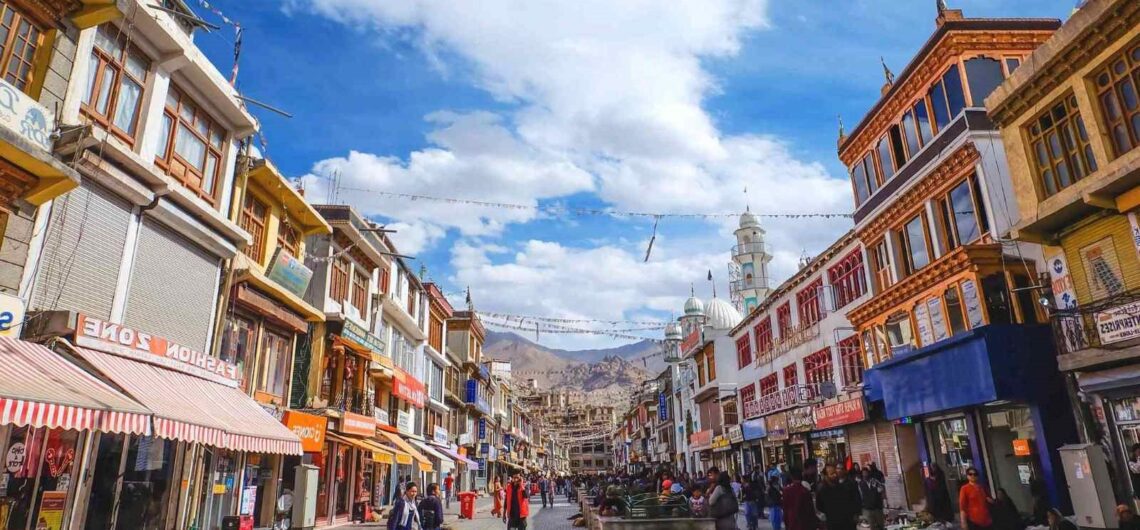

Leh Market, Where Color Does the Talking

The bazaar is not a sight; it is a texture you move through

You hear the market before you see it, and that feels right. Leh Market does not present itself like an object to be admired from a distance; it is a living strip of sound and friction. On a day when the wide blue seems to press down on everything, the bazaar presses back with human noise—bargaining, laughter, the crisp snap of a plastic bag, the soft thud of fruit being set down. Walking in Leh brings you into this sound slowly, as if you are entering a room where a conversation is already underway and you must find your place without interrupting.

Leh on foot changes the market’s scale. If you arrived by car, you might be tempted to treat it as a stop. On foot, it becomes an environment. The stalls and shops compress the afternoon into close quarters. Wool and leather and metal and spice sit beside each other like different dialects of the same language. There are scarves with a softness that makes you want to forget about weather entirely. There are copper pots that hold the light in their bellies. There are packets of masala whose smell is strong enough to feel like a hand on your shoulder.

European eyes often search for the “authentic” quickly, as if authenticity were a single object hidden somewhere among the goods. But the market’s authenticity is not a souvenir; it is in the choreography. People pass each other with a small turn of the shoulder that says, I see you. A shopkeeper talks fast, then shrugs, then smiles again, as if the entire bargain were less important than the fact that both of you are alive in the same afternoon. Leh on foot makes these gestures legible, because you are moving at the same speed as everyone else.

I stop at a row of textiles and touch fabric before I decide what I think. The weave tells a story more quickly than a label. Some cloth is all surface, flattering and insincere. Some has weight, the kind that falls properly and does not beg for attention. I feel my own mood shift with the texture. This is how the market speaks: through small, tactile truths. Walking in Leh Market, I realize I am not collecting objects; I am collecting evidence of how the city holds itself together—through trade, through patience, through the everyday art of making do without making a spectacle of it.

Above the roofs, the wide blue remains imperturbable, but here below, everything moves. A dog threads through ankles. A child runs with the seriousness of a small messenger. A monk steps aside for a cart. Leh on foot in the bazaar is less a route than a slow immersion, and when I finally find myself near the center of the market, I feel as if I have been folded into the city’s fabric, not merely invited to observe it.

Little purchases, big reliefs: how the market makes the walk easier

It would be dishonest to pretend that the market is only poetry. A bazaar is also an economy, and an economy has its practical comfort: it supplies what your body needs without ceremony. Leh on foot makes you aware of these needs quickly. The throat dries. The sun insists. The dust finds the edges of your shoes. In the market, solutions appear in modest forms: a bottle of water held in a refrigerator that hums like a small engine of mercy; a pair of socks thick enough to soften your step; a scarf that can be pulled up when the wind becomes too confident.

I watch a woman choose vegetables with the care of someone composing a meal, not a display. Her fingers test firmness; her eyes are precise. The gesture reminds me of European markets, but the light here makes everything sharper and the air makes every smell more immediate. I find myself hungry again—not for quantity, but for warmth. The idea of a café inside the Leh Market begins to feel inevitable, like the next sentence in a paragraph. Leh on foot does this: it turns appetite into a compass.

At a stall of dried fruit, apricots sit like small suns, wrinkled and sweet, their sugar concentrated by weather. I buy a handful and the vendor ties the bag with a quick twist, a movement so practiced it has the grace of calligraphy. I taste one and the sweetness feels less like indulgence than like fuel. The market is full of these understated exchanges. Money changes hands; so does a sort of mutual recognition. You are not the first traveler; you are simply today’s traveler.

The most practical thing the market offers is not an object but a change in your pace. You cannot rush in a crowd without becoming rude. So the market forces you to slow, and in that slowing your breath becomes steadier. Leh on foot often works this way: the city imposes a rhythm, and the rhythm becomes care. By the time I drift toward the café tucked among the stalls, I feel my body recalibrated. The wide blue is still strong above, but my attention is stronger now, and I am ready to sit for a moment—not as a tourist taking a break, but as a pedestrian allowing the afternoon to settle into its proper shape.

A Market Café, and the Art of Not Moving

Tea as a small interior, where the city passes like weather

The café is not grand; it does not need to be. Its charm is its refusal to compete with the market. Inside, the air holds a little more warmth and a little less dust. A kettle steams. Cups clink with the thin, bright sound of glass. Someone stirs sugar and the spoon rings softly, a domestic note amid the bazaar’s public noise. Leh on foot leads you here the way a long sentence leads you to a comma: not a stop, but a necessary breath.

I order chai, and the first sip is both sweetness and spice, then a gentle heat that travels down the throat like a reassuring hand. The mouth, which has been dry for an hour, becomes briefly alive again. The café offers a particular luxury to European readers who are used to cafés as stages: here, it is not a stage. It is a shelter. You sit with your scarf still around your neck because the door opens often. You watch people enter and leave without making a point of it. Outside, the market continues. Inside, the market becomes a soundscape, a distant tide.

I sit near a window where the wide blue cannot be seen, and that absence is a relief. The mind does not always want to be reminded of sky. Sometimes it wants a smaller ceiling, a lower light, a table that holds your elbows. The menu is worn; the edges of the paper have the soft fatigue of being handled many times. A dog sleeps near the door as if it belongs to the furniture. A radio plays something that sounds like a love song, though in this air even love songs feel a little thinner, a little more honest.

Walking in Leh, you learn that watching is a form of moving. In the café, you travel through faces. A young couple speaks quickly in a language I do not understand, but their gestures are legible: impatience, amusement, a small tenderness. A shopkeeper arrives, drinks his tea in a few efficient minutes, and leaves with the same economy of motion. A traveler in hiking boots studies a phone map with the seriousness of someone trying to tame a living thing. I do not envy him. Leh on foot does not require mastery. It requires presence.

When I finish my tea, I feel not merely fed but reassembled. The day outside is still bright and dry, but my thoughts have found their proper tempo again. I pay, stand, and step back into the market with the quiet confidence of someone who has remembered that an afternoon walk is not a race. The café has done its work: it has turned the bazaar’s noise into a background hum, and it has made space for the next part of the city—older, narrower, more shaded—to approach me without strain.

A brief sentence about desire, and how it changes on a Leh town walk

In European cities, a café pause often becomes a moment of planning. You spread your map, you decide what to see next, you appoint your own desires as if they were an itinerary. Here, the pause has a different function. It reveals desire in its simpler form. You want shade. You want to drink. You want to sit with your back supported. These are not small wants; they are the foundation of a civilized walk. Leh on foot makes desire modest and therefore accurate.

I notice, leaving the café, that I want fewer things than I wanted when I arrived in the market. Earlier, I touched fabrics with curiosity that was almost greedy. Now, I am content to let my hands remain at my sides. The market’s colors have imprinted themselves on my eyes; I do not need to carry them away. This is one of the quiet gifts of walking in Leh: it reduces the urge to possess. The city is so clear, so insistently present, that possession begins to feel redundant.

In places where the sky is this wide, you learn that the most intelligent souvenir is a change in your pace.

The wide blue does not flatter your ambitions. It reveals them, and then it asks if they are necessary. Under that question, the mind becomes selective. I choose a direction not because it is “next” on a route, but because I feel drawn toward quieter lanes. I have heard of Old Town Leh, of its narrow passages and older houses, but the name matters less than the promise of shade and stone. Leh on foot turns the city into a set of invitations you can accept or decline without guilt.

The market loosens its grip as I drift away. The sound thins. The stalls become fewer. The lanes narrow and the light changes character. Walking in Leh, you feel this shift on your skin before you notice it with your eyes. The air cools slightly in the shadow of taller walls. The dust becomes finer, less theatrical. A doorway appears with carved wood darkened by time. A staircase rises unexpectedly, as if someone built the city by stacking afternoons on top of each other. I follow the lanes with a pedestrian’s faith: not blind, but willing to be led by the simplest instinct—toward the place where the city keeps its older breath.

Old Town Leh, Where Shade Has Memory

Alleys like drawn curtains: intimacy, quiet, and the pleasure of cool stone

Old Town Leh does not announce itself with a gate. It simply begins, and the beginning is felt as a narrowing—of space, of sound, of the mind’s tendency to chatter. The lanes slip between walls that hold the day’s heat on their outer faces and keep a quieter cool within. Walking in Leh becomes gentler here. Your feet slow not because you are told to slow, but because the ground asks for attention. Steps appear without warning. Stone is uneven. A corner turns sharply and the light changes from bright to dim as quickly as a mood.

European cities have old quarters too, but their age often comes with signage and restoration and a certain pride. Here, the age feels less like pride and more like continuity. A doorframe is worn by hands. A threshold is polished by feet. A small window is covered by cloth that moves slightly when someone inside breathes near it. The street smells faintly of wood smoke and something sweeter, perhaps baking, perhaps incense. Leh on foot in Old Town is an education in restraint: you lower your voice without thinking, and you look without staring. Respect appears as posture, not as declaration.

I pass a wall where the plaster has cracked into a delicate map of time. In the cracks, dust has settled like fine flour. A child’s toy—something bright and plastic—rests incongruously against ancient stone, and the contrast is not tragic. It is merely true. Life continues. The wide blue is still above, but you see it only in fragments: a triangle of sky at the end of a lane, a strip of blue between roofs. The fragmentation is comforting. It makes the world feel human-sized again.

Walking in Leh’s older lanes, you become aware of your own body in a quieter way. Your breathing steadies. Your shoulders drop. The sun, which felt like a force in the market, feels like a distant presence here, filtered by architecture. You brush your hand lightly against a wall and the wall is cool, as if it has kept some of the night for you. The sensation is intimate, almost tender. You realize that the city is not only something you see; it is something that touches you back.

At a small junction, a woman carries water with a calm efficiency. She steps aside for me, then continues without fuss. I continue too, grateful not for her courtesy but for the reminder that this place is not a museum. Leh on foot becomes at its best in Old Town precisely because the city refuses to pose. It simply continues—lanes, steps, doors, shadows—asking you to match its quiet seriousness.

The walk becomes vertical: stairs, rooftops, and the way old places change your thoughts

In Old Town Leh, the ground has opinions. It rises in steps, it tilts, it surprises you with a staircase where you expected a lane. Walking in Leh begins to feel vertical, and that changes the mind’s rhythm. Climbing even a short set of steps makes you more attentive to breath, and attention has a cleansing effect. European readers might think of climbing as effort. Here, climbing feels like a small refinement: it strips away unnecessary speed.

Some stairways are narrow enough that you can touch both walls with your hands if you want to. The idea is childish and tempting. The walls are rough, the plaster granular. You feel the city’s age in your fingertips. At the top of one short climb, a rooftop appears—flat, practical, sunlit—and the view opens just enough to remind you again of the wide blue. The sky returns like a refrain in music, familiar but never the same. Leh on foot is full of these refrains: market noise fading into silence, shade giving way to glare, the city’s smallness constantly measured against that immense ceiling.

I pause at a vantage point where the lanes I have walked look like threads, thin and purposeful. A prayer flag flutters nearby, its fabric frayed at the edge as if time has gently worried it. The flag’s colors are bright, but the brightness is not loud. It is simply persistent. I think of how Europeans often treat color as decoration. Here, color feels like a form of endurance.

Descending again, I pass a doorway where someone is kneading dough. The smell is warm, yeasty, and it makes me hungry in a more serious way than the market did. Hunger in Old Town is not an impulse; it is a quiet agreement with the body. I begin to think of the palace, not as a landmark, but as the next change in altitude, the next shift in perspective. Leh on foot is, among other things, a series of perspective changes. Each one recalibrates what you consider important.

When the lanes widen slightly and the light becomes stronger, I know I am leaving the oldest part of town and moving toward a place where history sits higher—Leh Palace. The idea of height brings with it a mild humility. I adjust my scarf again, not because it is cold, but because the wind has begun to speak more directly. Then I walk toward the palace with the calm concentration of someone approaching a room that demands quieter footsteps.

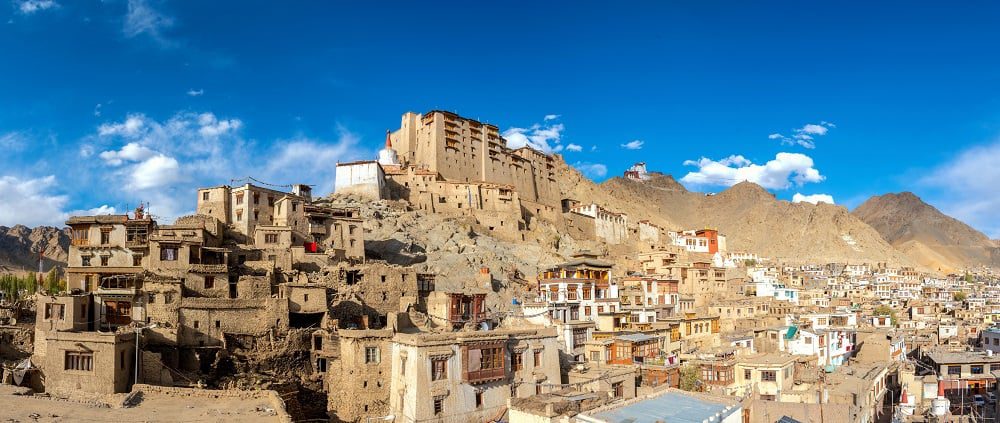

Leh Palace and Changspa Road, Two Kinds of Height

The palace: dust, windows, and the city made small beneath you

Leh Palace is a kind of pause you take with your legs. The climb toward it is not long, but it changes the body’s sentence. Breathing becomes more deliberate; the pace becomes less decorative. Walking in Leh up toward the palace, you begin to feel how altitude is not merely a number but a style of attention. You notice the way wind moves across open spaces, how it finds corners and makes them colder, how it lifts dust into brief, pale spirals that vanish as quickly as they appear.

Inside, the palace holds a different climate. Stone and old wood and enclosed rooms produce a quiet that is not emptiness but storage. Dust sits on surfaces with the confidence of something that knows it belongs. Light enters through windows and makes rectangles on the floor, and those rectangles feel like invitations to stand still. European museums often direct your gaze with labels. Here, your gaze is directed by the simple drama of light and shadow. I stand at a window and look down. The city becomes compact—roofs, lanes, courtyards—arranged like a careful hand laid them out. Above, the wide blue remains indifferent, but from this height it looks almost tender, as if it has decided to keep watch.

Leh on foot feels especially clear from the palace because you can see your own route implied in the city’s geometry. You recognize the market’s strip. You recognize the older lanes. You recognize Changspa Road stretching with a slightly looser confidence. The view does not make me feel triumphant; it makes me feel properly small. That is a better emotion to carry. It keeps the afternoon from becoming a performance.

I touch a wall and feel the coolness stored inside. My fingers come away dusty. It is a minor stain, a small proof that I have been here in a physical way. I like that proof more than a photograph. A photograph would be too neat, too clean. Leh on foot is not neat; it is dust and breath and the quiet work of keeping pace with a place that does not hurry to impress you.

When I leave the palace, the light outside feels sharper again, as if the world has returned to its public voice. The wind catches the edge of my scarf. I tighten it and begin to drift toward Changspa Road, looking forward to a different kind of walk—less historical, more social, where the city loosens its collar and allows itself a little evening softness.

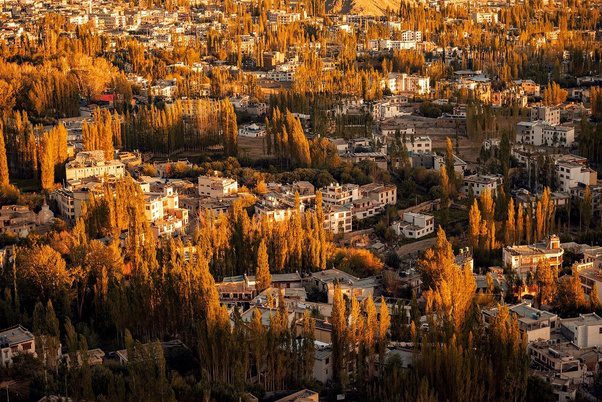

Changspa Road: a gentler current, where walking becomes social again

Changspa Road has the feel of a place that knows people will stroll. Its energy is different from the market’s compressed urgency and different again from Old Town’s quiet seriousness. Here, walking in Leh becomes openly pleasurable. Shopfronts offer small temptations—books, fabrics, snacks, souvenirs that are not ashamed of being souvenirs. Cafés and restaurants appear with the calm confidence of places that expect you to sit down. Leh on foot on Changspa Road feels like a conversation you can rejoin after a long silence.

European readers will recognize something familiar here: the rhythm of an evening promenade. But the details remain insistently local. The air is still dry; the sky is still enormous; the light still has that high-altitude clarity that makes everything look newly washed. People pass with an easy mixture—locals moving with purpose, travelers moving with curiosity, monks moving with quiet certainty. Dogs weave between ankles with practiced diplomacy.

I find myself smiling more often. Not because I am delighted in a shallow way, but because the road makes room for small pleasures. A shopkeeper holds up a scarf and the fabric catches the light with a softness that makes you want to touch it. A couple argues gently over directions, then laughs at themselves. A child swings an empty plastic bottle as if it were a toy instrument. The sound is light and ridiculous and perfectly suited to the hour.

Leh on foot remains, even here, a practice in pacing. Changspa invites you to linger, but it also invites you to be selective. You do not need to enter every shop. You do not need to sample every menu. The best way to walk in Leh is to let desire remain precise. I choose one restaurant not because it has the loudest promise, but because it has a quiet steadiness—a few tables, warm light, the smell of soup drifting out like an unforced welcome.

As I approach the restaurant, I notice the first true fatigue in my legs. It is not unpleasant. It is the kind of fatigue that makes dinner feel deserved, and makes the next climb—to Shanti Stupa—feel like a choice rather than an obligation. Leh on foot offers you this sequence gently: walk, eat, walk again, and let the wide blue above change its tone as afternoon slips toward evening.

Dinner on Changspa, Then the White Quiet Above Town

A table that anchors the body: warmth, salt, and the relief of sitting

The restaurant on Changspa Road is modest in the way good things often are. It does not shout. It glows. Inside, the air holds warmth like a careful secret. Chairs feel sturdier than they did an hour ago. My legs, which have been carrying me through market friction and Old Town steps and palace height, accept the seat with a gratitude that is almost comic. Leh on foot makes you aware of the pleasure of sitting in a way that a car never will. Sitting becomes a small ceremony of return to the body.

I order something warm—soup first, then a plate that carries rice and vegetables with a sensible generosity. Steam rises and touches my face. The smell of cumin and something green and fresh loosens the last tightness in my chest. European readers might think of “local food” as an experience to collect. Here, the meal is simpler and more serious. It is not a story; it is a repair. Salt restores clarity to the tongue. Heat restores confidence to the hands.

I watch the small details of the table as if they were part of the city’s language. Condensation gathers on a glass, then slides down in slow, decisive lines. Cutlery has that familiar metallic sound that instantly makes any place feel temporarily like home. The menu is slightly worn; the corners curl. Someone at another table laughs softly, then lowers their voice as if remembering the thin air. Outside, the road continues to carry pedestrians, but the sound is filtered through the wall, softened into a hum.

Leh on foot changes the way you eat. You are not eating to refuel for an itinerary; you are eating to keep the evening humane. I find myself chewing more slowly, letting the warmth remain in my mouth, letting the meal do its quiet work. The wide blue beyond the walls is starting to deepen, shifting from a harsh midday clarity to a richer tone. I know, without checking a clock, that this is the right time to begin thinking of the stupa. Not because it is a “sunset spot,” but because the body, repaired by dinner, is ready again for a climb.

When I pay and step back outside, the air feels cooler and cleaner. The scarf becomes useful again. I tighten it and turn my feet toward the upward path. Leh on foot, in the evening, becomes a different kind of walking: less about commerce and lanes, more about breath and sky, about leaving the city’s small noises behind and entering a quieter register.

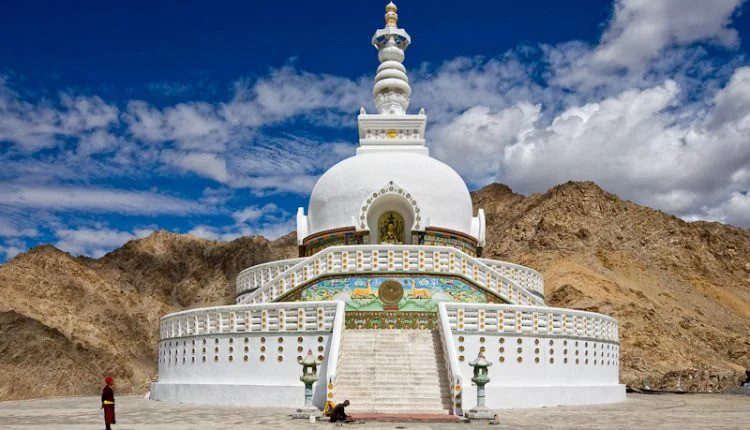

Shanti Stupa: wind, steps, and the wide blue made luminous

The climb toward Shanti Stupa is not an ordeal, but it is honest. It asks you to count your breath in a quiet way, to accept that your legs are not machines and your lungs are not decorative. Walking in Leh up toward the stupa, the city begins to fall away behind you. The sounds of Changspa thin, then disappear. The air grows cooler. The wind becomes more direct, as if it has fewer walls to negotiate. It lifts the edge of my scarf and reminds me that even in calm weather, the hill belongs to the sky.

As I climb, the wide blue changes again. In the late day it is less severe, more layered. It holds faint gradients—paler near the horizon, deeper above—like watercolor that has been allowed to dry without interference. The stupa appears white and composed, a kind of punctuation mark on the hillside. I do not approach it with triumph. I approach it as I approach any quiet place after a long afternoon: with relief, with a little humility, and with the hope that I will not ruin it with too much thought.

At the top, the city is small. Leh looks like a handful of roofs held together by lanes, market strips, and the unspoken agreement of people who know how to live under a vast sky. Leh on foot has made that smallness feel intimate rather than insignificant. I can trace the afternoon in my mind: the guesthouse door, the market’s bright pulse, the café’s warm pause, the shaded memory of Old Town, the palace’s stored silence, Changspa’s softer current, dinner’s repair. Each part has left a residue—dust on shoes, warmth in the belly, a steadier rhythm in the breath.

The stupa itself is quiet in a way that does not demand reverence but invites it. A few visitors stand without speaking much. The wind moves through prayer flags nearby, making them snap lightly like small, cheerful whips. The sound is sharp, then gone. The wide blue above holds everything—city, hill, people, silence—without judgment. For a moment, I feel the peculiar peace that comes when a place does not ask you to be anything more than present.

Leh on foot ends here not because the route is complete, but because the day has reached its cleanest sentence. I stand, breathe, and let the evening settle on my shoulders like a shawl. Then, before I descend, I look once more at the city and understand a simple truth: the wide blue is not something you visit. It is something you learn to carry, lightly, in the way you carry a good afternoon—without squeezing it into an explanation.

FAQ

Is Leh easy to explore on foot for first-time visitors?

Leh is remarkably walkable, but it rewards a gentle pace. On Leh on foot, the main adjustment is not distance; it is altitude and brightness. If you allow pauses—shade, tea, short rests—your body settles quickly. Many first-time visitors find that walking in Leh becomes easier after the first unhurried afternoon.

How long does this Leh on foot route usually take?

The full afternoon—guesthouse to Leh Market, a café pause, Old Town lanes, Leh Palace, Changspa Road, dinner, then Shanti Stupa—can take anywhere from four to seven hours, depending on how often you stop. Leh on foot is at its best when you linger: the market slows time, and the café makes the afternoon feel wider.

When is the best time of day for walking in Leh and visiting Shanti Stupa?

Late afternoon into early evening is ideal because the light softens and the air cools. Walking in Leh in the harshest midday brightness can feel tiring, while later hours make the climb to Shanti Stupa calmer and more comfortable. The wide blue also gains depth toward evening, which changes the whole mood of Leh on foot.

What should I wear for a comfortable Leh town walk?

Layers are the simplest answer: a light jacket or warm layer, a scarf for wind and dryness, and comfortable shoes for uneven stone. Sunglasses and sun protection help because the light is clear and persistent. Leh on foot feels most elegant when your clothing supports your pace rather than competing for attention.

Conclusion: What This Walk Leaves in Your Hands

Clear takeaways from a small city under a wide blue

Leh on foot is not memorable because it is difficult; it is memorable because it is precise. The small city gives you distinct chapters, each with its own texture, and the wide blue above ties them together like a single, long thread. If you want clear takeaways, they are simple, and they come directly from the afternoon’s sensations rather than from rules.

- Let pace be your plan. Walking in Leh becomes easier and richer when you accept pauses as part of the walk, not interruptions.

- Use the market for more than shopping. The Leh Market is a rhythm lesson; it slows you into the city’s real tempo and makes your breath steadier.

- Give yourself a café comma. A short chai pause turns the bazaar’s noise into background and prepares you for quieter lanes and older stone.

- Old Town teaches respect without words. Shade, narrow stairs, and worn thresholds encourage quieter movement and calmer attention.

- Height is perspective, not achievement. Leh Palace and Shanti Stupa both make the city small; the point is not conquest, but clarity.

- Dinner matters. A warm meal on Changspa Road repairs the body and makes the final climb feel chosen, not endured.

European readers often look for a “best route” when they search for a Leh walking route. The better question is: what kind of afternoon do you want to carry afterward? Leh on foot answers that question by giving you small, accurate pleasures—shade at the right moment, tea when the throat asks for it, silence when the mind needs it, a view when the day is ready to become simple. The route works because it respects the body and respects the city.

A final closing note under the wide blue

When you return downhill, the city will feel closer—less like a destination, more like a familiar room. That is what a good walk does. Leh on foot does it with unusual purity. The wide blue will still be overhead, patient and immense, and the small city will still be busy with markets and lanes and dinners and dogs asleep in sun. But something in you will have changed its tempo. You will walk a little more honestly, breathe a little more deliberately, and carry the afternoon not as a story you must prove, but as a quiet certainty—like warmth held in stone after the sun has moved on.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.Through intimate travel columns, she follows ordinary routes—markets, lanes, rooftops—

until they reveal the extraordinary patience of place.