Where the Road Softens Into Villages and Memory

By Declan P. O’Connor

1. Opening Reflection: The Corridor Before the High Plateau

Why this quiet stretch between Leh and the unseen Changthang matters

If you follow the road east from Leh, you do not arrive immediately at the wild emptiness of the high plateau. Instead, you move through a quieter corridor of villages, fields, monasteries, and river bends that feel less like a transit zone and more like a long threshold. This stretch from Leh to the first hints of the Changthang is not yet the famed high-altitude desert, nor is it the dense, touristed town center. It is something else: a lived-in landscape where the ordinary days of Ladakhi life still hold their ground against the pressure of speed, itineraries, and bucket lists.

The Leh–Changthang corridor matters because it is where most travelers reveal their habits. Some treat it as dead space, a blur outside the car window between more photogenic destinations. Others allow the road to slow their assumptions down. Here, near the Indus, the villages that line the river – Choglamsar, Shey, Thiksey, and Matho – offer a first education in what it means to inhabit altitude not as spectacle but as home. Further along, as the road climbs past Stakna, Stok, Hemis, Karu, Sakti, and Takthok, the mountains draw closer, the air dries, and the conversation changes from “What can we see?” to “How do people live here, day after day?”

In this corridor, the map is less important than the pace at which your attention learns to walk.

To travel from Leh to the threshold of Changthang is to move through a chain of places that quietly insist on their own dignity. It is here, before the road tips over the high pass, that you begin to understand Ladakh not as a backdrop for adventure, but as a web of villages where light, work, and memory are still braided tightly into each day.

2. The Indus-Side Settlements: Fields, Monasteries, and Old Kingdom Echoes

Choglamsar: a village of crossroads, classrooms, and quiet resilience

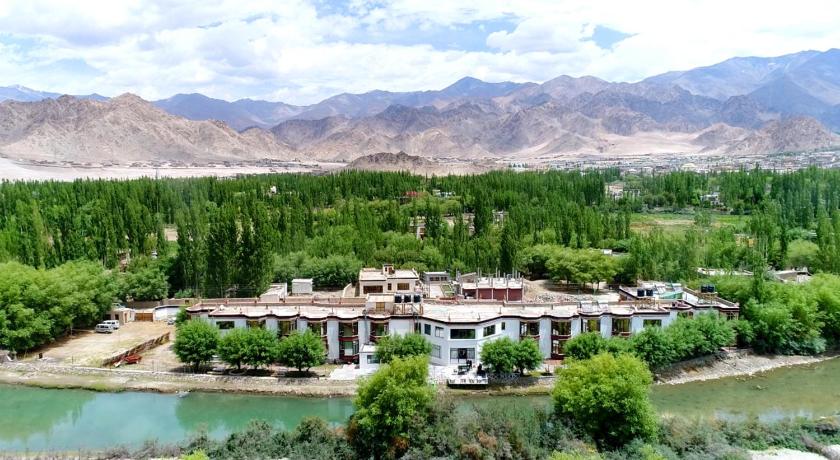

For many visitors, Choglamsar appears first as a cluster of buildings on the way out of Leh, a semi-urban sprawl that seems neither fully village nor fully town. But if you pause long enough, the place rearranges itself. Beyond the main road, lanes drift towards the Indus where fields still stretch in wavering green patches, irrigated by channels that have little patience for the categories of urban and rural. Here, families who arrived as refugees, traders, or workers share space with older Ladakhi households whose grandparents remember when Leh felt like a distant outpost rather than a busy hub.

Choglamsar is a village of crossings. It hosts schools, small monasteries, community centers, and homes where several languages are spoken in the same courtyard. The Leh–Changthang corridor feels particularly human here: young people commute to Leh for work or study, then return in the evening to the sound of dogs, prayer flags, and the low thrum of generators. Travelers who stay a night or even a long afternoon often say that this is where the story of their journey subtly changes. Instead of asking only about monasteries and passes, they start asking about wages, winter heating, exam results, and what it means to raise children on the edge of a transforming town.

The Indus river runs nearby, a constant reminder that Choglamsar is inseparable from the broader valley. In this portion of the Leh–Changthang corridor, the village teaches you that before there are spectacular landscapes, there are people who must simply get through the week. To notice that is to begin traveling differently.

Shey: palaces, water channels, and a soft light on stone

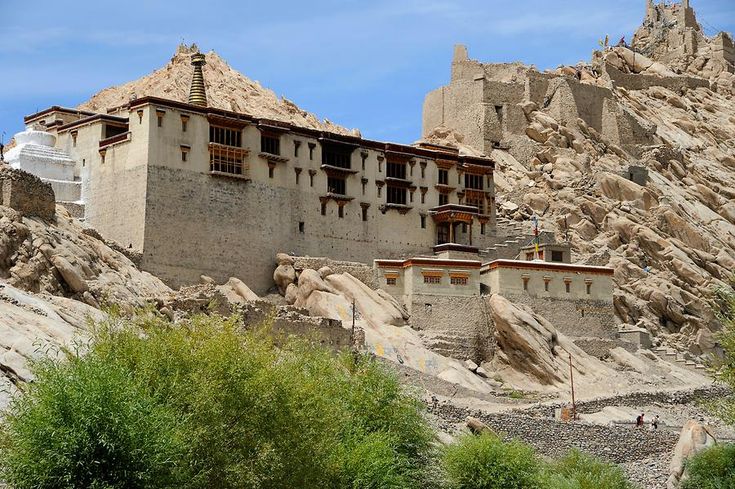

Further along the Indus, Shey sits with a kind of understated confidence. The ruined palace and large seated Buddha that watch over the village tend to dominate photographs, but in daily life it is the water that matters most. Channels split off from the river and run through the fields with a quiet determination, threading between poplar and willow, feeding barley and vegetables. When the afternoon light drops, it lands on stone, water, and leaf with a softness that is hard to forget.

Shey carries the echo of Ladakh’s old kingdom days. Walking between the palace hill and the fields below, you feel the layers of history stacking up: kings who once chose this as a seat of power, monks who turned slopes into stairways of prayer, farmers who still count on the same soils. In the Leh–Changthang corridor, Shey serves as an early reminder that the region is not just high desert but also a long experiment in governance, irrigation, and belief. The faded murals and the glint of the Buddha’s face above the village seem less like relics and more like quiet shareholders in the present.

Stay a little longer and you see how Shey lives now. Children walk home from school along the irrigation channels; elders sit in sunlit corners, spinning wool or prayer wheels; small homestays have grown up alongside traditional houses, careful not to overshadow them. You begin to sense that this is not a postcard of old Ladakh but a living compromise between continuity and change, still anchored by the palace rock that holds the horizon in place.

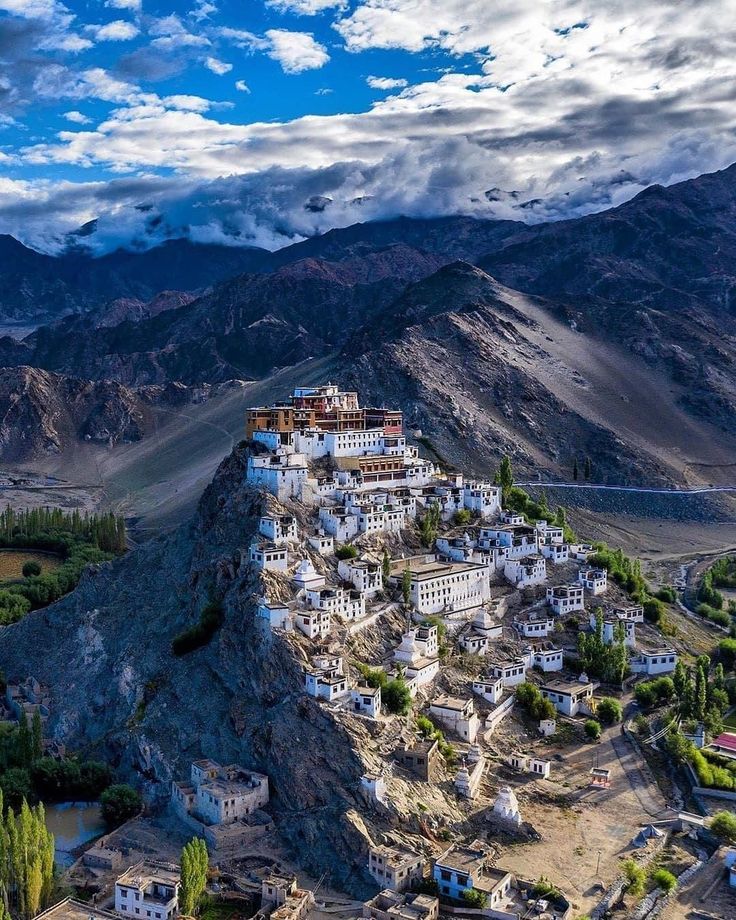

Thiksey: where the monastery watches the valley like a long memory

Thiksey rises in tiers from the valley floor, its monastery stacked along the ridge like a series of white stones carefully placed by a meticulous hand. Most travelers know the monastery through a handful of images: the great Maitreya statue, the breakfast chants, the view of the Indus valley unfurling below. But Thiksey as a village is larger, slower, and more ordinary in the best possible sense. Behind the monasteries and guesthouses, paths run between houses, fields, and stables where daily routines unfold with little interest in visitor timetables.

In the Leh–Changthang corridor, Thiksey is a kind of balcony. From here you look out toward both Leh and the direction of the unseen plateau, sensing how the valley stitches them together. The monastery bells measure the day, but so do school bells and the clank of milk cans being carried from cowsheds to kitchens. In the early morning, as the first sunlight strikes the monastery walls, there is a sense that the village is being gently woken by something older than the road traffic below.

Walk down from the monastery and you find small shops selling everyday goods, dusty lanes where children kick a ball, and fields of barley that shimmer when the wind climbs the valley. Thiksey’s power lies not only in its religious architecture but in the way the village frames it: a community that has learned how to live in the monastery’s shadow without being swallowed by it. This balance between sacred and ordinary is part of what makes the corridor from Leh to the Changthang threshold feel so humanly scaled.

Matho: a side valley where silence has its own altitude

Turn away from the main road toward Matho and you feel the temperature of the journey shift. The valley narrows, the traffic thins, and the soundscape changes from horns and engines to wind and the occasional bark of a dog. Matho sits cradled in this side valley, its monastery perched with a slightly watchful air and its houses clustered around fields that have been coaxed from thin soil with centuries of patience.

Matho is known among Ladakhis for its oracles and monastic rituals, but for many visitors its greatest gift is the quality of its silence. It is not the emptiness of a remote pass but a woven silence layered with village life: the scrape of a shovel in a field, the murmur of conversation on a rooftop, the low chant of evening prayers drifting along the slope. Standing here, on the Leh–Changthang corridor yet slightly aside from it, you sense how crucial these side valleys are to the region’s emotional geography.

If you stay overnight, the stars feel closer, and the valley’s darkness pushes your attention inward. The route from Leh toward Changthang becomes less of a line on a map and more of a series of nested valleys, each with its own mood. Matho’s mood is introspective. It teaches you that not all thresholds shout. Some whisper, quietly asking whether you are willing to listen before you climb higher.

3. The Road Turns Toward the Mountains: Transition Villages of the Eastern Route

Stakna: a monastery on a rock that divides the river and the day

Back on the main road, the Indus bends toward Stakna, where a monastery sits atop a slender rock formation like a ship anchored midstream. The scene is dramatic enough to belong on a cinema screen: river, rock, monastery, and mountains arranged in a composition that seems almost deliberate. Yet Stakna as a village lives in the spaces around this icon. Houses and fields occupy the flatter land, their routines only intermittently interrupted by the presence of visitors who come for the view.

Stakna marks a psychological turn in the Leh–Changthang corridor. Up to this point, the road feels dominantly riverine, following the Indus as it curls between banks of cultivated land. From here on, the mountains begin to assert themselves more firmly. Winds grow sharper; the sky feels wider. In the village, however, the day is still structured by the ordinary: cows led to pasture, children sent to school, monks climbing the steep steps to morning prayers.

What is striking in Stakna is how quickly the spectacular recedes into the background when you pay attention to life at ground level. A woman bends over a field to clear stones. A boy rides a bicycle along the dusty roadside, tracing loops as if to draw his own map of the day. The monastery’s silhouette watches all of this, but it does not dictate it. Stakna quietly reminds the traveler that even the most photographed landscapes are first and foremost home to someone else.

Stok: a village of kingship, hearth smoke, and soft pathways

Across the river from the main road, Stok stretches up a valley that feels immediately more intimate. The village is best known for its palace, the current residence of Ladakh’s royal family, and for the small museum that holds artifacts from earlier periods of the kingdom’s life. Yet Stok’s deeper character lies in its lanes and courtyards, where smoke curls from kitchen chimneys and paths thread between fields, shrines, and stone walls.

In the larger story of the Leh–Changthang corridor, Stok functions as a living archive. Royal history is not kept in glass cases alone; it is also present in the way houses are built, festivals are organized, and stories are told in winter rooms over butter tea. Travelers who linger here, staying in family homestays rather than rushing back to Leh, often leave with a sense that they have glimpsed an older structure of life that still quietly informs the present.

The village encourages walking rather than driving. Moving on foot along its soft pathways, you notice small chapels, irrigation channels, and the intricate geometry of stacked stones that keep terraced fields in place. Children shout greetings; elders nod from low doorways. From higher vantage points, you can see how Stok gazes both back toward Leh and outward to the mountains that close the valley. It is neither remote nor fully absorbed into the town’s orbit. Instead, it holds a middle position, a dignified pause in the journey toward the higher, harsher lands beyond.

Hemis: a forested valley that holds its own silence

Hemis lies off the main Leh–Changthang route, tucked into a side valley that feels unusually green by Ladakhi standards. The road winds upward through stands of trees, past small waterfalls and shaded corners where the air carries a different coolness. The monastery, one of the largest in the region, is what draws most visitors. Its festival, with masked dances and crowded courtyards, has been photographed and promoted for decades. Yet what stays with many travelers is not the spectacle but the way the valley itself seems to hold sound.

When the festival is not in session, Hemis is a quieter place. The village below the monastery runs on a timetable of fields, livestock, and school days. The forested slopes give the impression that the valley is listening: to footsteps on stone stairways, to the mumble of prayers, to the clatter of dishes in kitchen courtyards. In the context of the Leh–Changthang corridor, Hemis offers a reminder that altitude can be softened by trees and shade, that mountain life is not only exposure and glare.

Stay a night and you begin to distinguish the sounds of the valley. Wind in the leaves feels different from wind over bare rock; a stream behind the guesthouse has its own tempo. This layered silence, punctuated by occasional monastery horns, recalibrates the body. It prepares you, in a subtle way, for the more open acoustics of the high plateau that still lies beyond the mountains. Hemis teaches that before you step into wide emptiness, it helps to spend time in a place where sound is gentled and returned to you more slowly.

Karu: the trading node where the corridor changes tempo

By the time you reach Karu, the journey’s rhythm has changed again. Here the Leh–Changthang corridor tightens into a junction where roads diverge: one toward Hemis and its side valleys, another toward the high pass that leads eventually toward the plateau, and another looping back toward different Indus settlements. Trucks idle, tea stalls do brisk business, and a steady stream of vehicles passes through, carrying fuel, goods, and people to places far beyond the village.

Karu is often described as “just a junction,” but that undersells it. In a region where geography can make movement fragile, junctions are lifelines. The village is built around the logistics of movement: mechanics’ workshops, supply depots, small restaurants that know how to feed both drivers in a hurry and travelers waiting out a change in weather. Children grow up fluent in the sight of different uniforms, license plates, and languages drifting through.

For travelers along the corridor, Karu is where the journey demands a decision: continue along the Indus, retreat toward Leh, or commit to the climb toward Sakti, Takthok, and the high pass. That choice is not purely logistical. It is a small test of appetite – for altitude, for remoteness, for the uncertainty that comes with leaving the river valley behind. Sitting over a cup of namkeen chai in a roadside stall, you can watch others make that decision, sometimes casually, sometimes with visible hesitation. Karu is the place where the corridor’s quiet villages begin to give way to the psychological frontier of the mountains.

Sakti: a green village leaning into the mountains

From Karu, the road turns decisively upward toward Sakti, a village that stretches across a bowl of green tucked at the foot of serious mountains. Fields follow the contours of the land, stitched together by stone walls and irrigation channels that glint in the sunlight. Houses sit at varying elevations, some close to the road, others perched higher where the view back toward the Indus valley feels almost theatrical.

Sakti is where the Leh–Changthang corridor begins to feel truly transitional. The air is drier, the light more insistent, yet the presence of agriculture softens the ascent. You see people moving along narrow footpaths with bundles of fodder, children walking in small groups to school, and elders taking the sun along south-facing walls. The village’s relationship to the road is pragmatic: it brings supplies, visitors, and news, but daily life still orbits around fields, animals, and the rhythm of water.

For travelers, Sakti offers a chance to integrate. The movement out of Leh, through the Indus-side villages, and up into this higher valley becomes more than a series of stops on a map. It turns into a story about gradient – not just of altitude, but of noise, pace, and expectation. Spend an extra day here and the temptation to push onward quickly toward the pass loosens its grip. You begin to see the value of dawdling in a place where the mountains feel close but not yet overwhelming, and where the threshold to the high plateau remains just out of sight around the next bend.

Takthok: the cave, the monastery, and the stories that cling to stone

Beyond Sakti, the road narrows again before it reaches Takthok, a village whose monastery grew out of a cave and whose name – “rock roof” – tells you something about its character. The monastery is literally built into the rock, its interior spaces feeling closer to earth than sky. Pilgrims and visitors come for the cave, the murals, and the sense of being sheltered by geology itself. Outside, the village spreads modestly along the slope, its houses adapting to the terrain with the patience that mountain life demands.

Takthok sits at an interesting point in the Leh–Changthang corridor. It is no longer the broad Indus valley, but not yet the bare highlands that lie beyond the pass. The stories here cling to stone: tales of yogis meditating in the cave, of festivals that once drew larger crowds, of winters that stretched longer than expected. The rock itself seems to participate in these narratives, giving the monastery and village an almost cave-like intimacy.

To walk through Takthok is to move between light and shadow. Narrow lanes dip under overhangs, then open suddenly to the sky. Courtyards are bounded by stone walls that hold warmth long after the sun sets. Travelers who pause here often find that their sense of time shifts; days feel both shorter and denser. The approaching high pass looms in the mind, but the village insists on its own importance. It suggests that before you ascend fully into exposure, you might do well to spend time in a place that knows how to live tucked against stone, making shelter from the very mountains that threaten.

4. Approaching the High Pass: Points Where the Landscape Begins to Thin

Zingral: a high-altitude outpost framed by wind and watchfulness

Leaving Takthok, the Leh–Changthang corridor begins to shed the last traces of comfortable vegetation. The road climbs sharply, hairpin after hairpin, until the fields fall away and the slopes turn a palette of stone, dust, and the occasional strip of hardy grass. Zingral appears not so much as a village in the traditional sense but as a high-altitude outpost: a cluster of military installations, temporary shelters, and roadside tea points that cling to the margins of the road.

Life here is calibrated to exposure. The wind has a different voice – louder, more insistent, sometimes carrying dust, sometimes a fine dry chill that gets under the skin. For those stationed here, days are a mix of routine vigilance and simple maintenance: clearing snow or stones from the road, checking vehicles, managing supplies. For travelers, Zingral is where the comfort of the lower corridor drops definitively away. The air is thinner; breathing takes more effort. Conversations shorten, not out of disinterest but out of respect for lungs that have to work harder.

Yet even in this austere setting, human traces soften the landscape. Prayer flags flap from poles, their colors standing out against the muted rock. A kettle steams in a small shack where drivers stop for tea and instant noodles. There are jokes shared between soldiers and truckers, stories exchanged about weather, breakdowns, and the state of the road beyond the pass. Zingral quietly reveals that even at these thresholds, the Leh–Changthang route is held together as much by relationships and routines as by asphalt and engineering.

Tso Ltak: the last bend before the high white of the pass

A little higher still lies Tso Ltak, another waystation on the climb that feels like a final punctuation mark before the sentence of the pass. Here, the landscape is nearly bare. Only low cushions of vegetation and the occasional hardy flower break the monotony of stone. The road, having already asserted its dominance over the slope, now threads the last approach to the ridge with a kind of grim determination.

Tso Ltak is less a fixed settlement than a recurring pattern of presence: parked trucks, a temporary canteen, small groups of people adjusting to the altitude before moving on. On some days, it is bright and almost cheerful, with travelers taking photographs, laughing at their own breathlessness, and marveling at the views back down the valley. On others, it is a place of waiting, as weather closes in and vehicles sit idle while drivers gauge the risk of continuing.

Standing here, looking back along the route you have taken from Leh – over the villages by the Indus, through the side valleys, up past Sakti and Takthok – you realize that the corridor has been doing quiet work on you. Tso Ltak is where this becomes clear. Your sense of distance has changed; what once felt far now seems connected by a chain of recognisable places. The threshold to the Changthang is close, but it is no longer an abstract idea. It is a continuation of a story that began in ordinary kitchens, fields, and monasteries along the way.

5. Closing Meditation: Why These Villages Matter Before the Horizon Opens

Lessons in slowness, attention, and the meaning of moving through rural Ladakh

Travel writing likes to jump directly to the spectacular: the highest pass, the bluest lake, the most remote village. Yet the Leh–Changthang corridor suggests a different structure for a journey. It asks you to spend time in the places that lie between headlines: the village by the river, the side valley with its small monastery, the trading junction, the green bowl at the foot of the mountains. These are not just staging grounds; they are the scaffolding that makes the rest of the landscape intelligible.

In these villages, you learn slowness not as an aesthetic choice but as a practical rhythm. Water flows through channels at the speed gravity allows. Crops ripen on their own schedule, indifferent to visitor check-out times. Children walk long distances to school simply because that is how the village is laid out. To enter this rhythm, even briefly, is to feel your own assumptions about efficiency and urgency loosen.

Attention, too, changes. The longer you stay in the corridor, the more you notice: how the color of the Indus shifts with season and light; how fields in Shey differ from those in Sakti; how the same wind that whips prayer flags at Zingral once rustled poplar leaves outside a house in Thiksey. The journey from Leh to the threshold of Changthang becomes less about collecting sights and more about following a continuity of life across changing altitudes and geologies.

This is why the villages matter before the horizon opens. They anchor the spectacular in the ordinary. They insist that before you marvel at empty plains and big skies, you should understand at least a little about where the bread is baked, where the water is diverted, where children do their homework. Without that understanding, the high plateau risks becoming just another backdrop. With it, the landscape becomes part of a longer, humbler narrative of how people have learned to inhabit difficult beauty.

FAQ: practical questions for traveling the Leh–Changthang corridor

Is it worth stopping overnight in the villages between Leh and the high pass, or is a day trip enough?

If you treat the corridor as a mere transit route, a single day will take you from Leh to the threshold and back. But the character of these villages – their fields, kitchens, and conversations – only really reveals itself when you slow down. One or two overnight stays in places like Shey, Thiksey, Stok, Sakti, or Takthok change the texture of the journey. You begin to recognise faces in the lanes, to understand how light moves across the valley at different hours, and to feel altitude as a gradual story rather than a sudden shock. For most travelers, one night in the lower Indus villages and one higher up toward Sakti or Takthok offers a meaningful balance between comfort and immersion.

How should I think about acclimatization when traveling this corridor toward higher country?

The villages of the Leh–Changthang corridor double as natural acclimatization steps. Leh already sits at significant altitude, and the gradual movement through Choglamsar, Shey, Thiksey, and the side valleys allows your body to settle into the rhythm of the air. When you then continue to Sakti, Takthok, Zingral, and Tso Ltak, you are asking less of your lungs than if you rushed straight from town to the highest point in a single push. Walking short distances, drinking plenty of water, and sleeping even one night away from the busiest part of Leh all help. Think of acclimatization not as a medical checklist alone but as an opportunity to notice the differences between villages along the way.

Can I visit these villages independently, or do I need a guide and driver?

Many parts of the corridor can be explored independently by confident travelers, especially the Indus-side villages and those close to Leh. Local buses, shared taxis, and hired cars all operate along the main routes. However, having a knowledgeable local driver or guide can deepen your understanding of what you are seeing. They can point out irrigation structures you might overlook, introduce you to families offering homestays, and navigate the small practicalities that are invisible until they suddenly matter. In the higher stretches near Zingral and Tso Ltak, where conditions change fast, local knowledge also becomes a safety asset. A mixed approach – some independent walking or wandering, combined with segments supported by local expertise – often works best.

Conclusion and final note: carrying the corridor with you

When you eventually cross the high pass and step onto the first expanses of the plateau beyond, it can be tempting to let the earlier part of the route fade into background. The light is wider there, the silence deeper, the sense of isolation stronger. Yet the villages between Leh and the threshold of Changthang continue to do quiet work in the imagination long after the trip is over. They become reference points: the sound of a water channel in Shey, the tiered houses of Thiksey, a shared cup of salty tea in Karu, the cave-cool shadows of Takthok.

To remember them is to resist the habit of treating landscapes as empty except for our journeys through them. The corridor reminds you that every view you admired was already someone’s daily commute, someone else’s chore route, someone’s childhood playground. This understanding does not diminish the beauty of the scenery; it deepens it. The high plains beyond the pass feel different when you know which villages lie behind you, holding their own fragile balance between tradition and change.

Carry that awareness home. Let it shape how you look at the places you consider ordinary in your own life: the suburbs, small towns, and commuter belts that rarely appear on postcards. Somewhere, someone is traveling quickly past them, seeing only blank space between destinations. Having once moved slowly through the Leh–Changthang corridor, you are less likely to make that mistake. You have learned that some of the most important parts of any journey take place in the quiet, inhabited stretches between the peaks.

If you return to Ladakh, you may well head again for the lakes, passes, and viewpoints. But perhaps, this time, you will leave extra days in your itinerary for the villages that hold the corridor’s light – to sit in a courtyard in Shey, to listen to evening bells in Thiksey, to walk the lanes of Stok at dusk, or to watch the sky darken over Sakti. The horizon will still be waiting beyond the pass. The real question is whether you will allow yourself to arrive there changed by the villages that brought you to its edge.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh, a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life. Through essays on villages, valleys, and high plateaus, he invites readers to slow down, pay attention, and travel with a deeper sense of responsibility and wonder.