The Day the House Counts Water in Containers

By Sidonie Morel

A kitchen that starts with plastic, not a tap

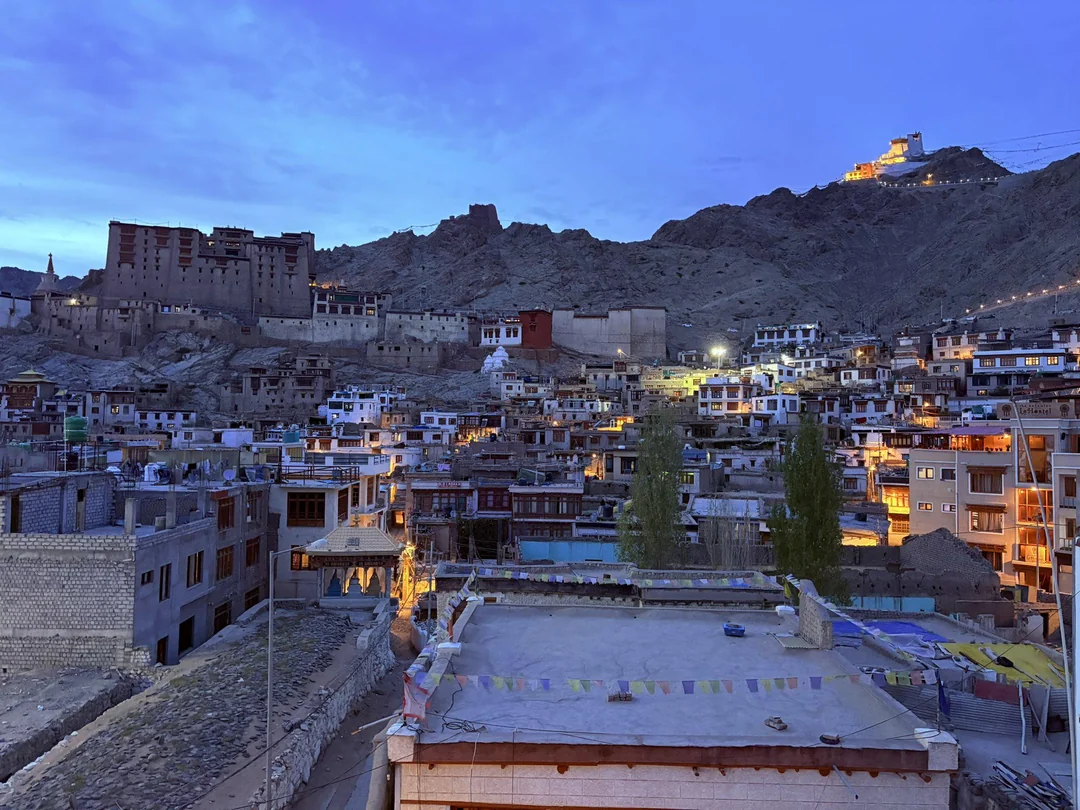

In Leh, the first object to move in the morning is often not a kettle. It is a container. A yellow jerrycan, scuffed on the corners, sits near the door where shoes and dust collect. It has a screw cap with a ring of grit caught in the thread. The jerrycan is not decoration and not an emergency measure. It is part of the house’s basic equipment in the same way a ladle or a broom is.

When water arrives through a pipe, it announces itself with sound and speed. Here, water often arrives by schedule and by effort. If there is a municipal supply line, it may run for a short window. If it does not run, there is a standpipe, a shared tap, a tanker, a spring, or a neighbour with a connection strong enough to lend a few litres. In many homes, the kitchen measures water as volume in containers rather than as a stream.

The counter is set up for this. A wide steel basin sits ready to catch drips. A small cloth is folded twice and placed beneath the mouth of the container because a wet floor in winter can turn to ice, and because water is not treated as something to spill. A second container—smaller, handled—waits for the daily work that follows: washing vegetables, rinsing rice, cleaning a cup, wiping hands, diluting soap for a quick scrub of a pot. The water’s path is visible: from jerrycan to basin to kettle, from basin to bucket, from bucket to the house’s drain or to a corner outside where greywater is poured onto bare earth.

Nothing here requires a speech about scarcity. It is conveyed by how the kitchen is organised. A tap is a point source; a container is a plan.

What “running water” means when it does not run

In neighbourhoods on the edges of Leh, and in villages nearby such as Choglamsar, Saboo, and Phyang, water can be present in the landscape and unreliable at the sink. Pipes follow roads and new houses. Old channels follow fields. Springs appear in certain folds of land. Supply can depend on season, temperature, pressure in the line, and maintenance upstream.

A household learns to translate these variables into routine. Containers are washed and stacked where they can dry quickly. Caps are checked because a missing cap means dust. In winter, the path to an outside tap is kept clear of ice. In summer, when daytime temperatures rise and demand increases, the same path can be crowded by neighbours holding buckets, plastic cans, and metal pots. If a tanker arrives, people shift their tasks around it. Cooking waits. Laundry waits. A child is sent to stand in line while an adult finishes feeding animals or turning soil in a small garden patch.

From the perspective of the kitchen, the Ladakh water crisis is not an abstract phrase. It is the difference between boiling water for tea immediately and boiling it after a walk to a tap. It is the difference between rinsing lentils in three changes of water and in one. It is the difference between washing a floor with a bucket and wiping it with a cloth.

Following the water downhill to understand why it must be carried uphill

From Leh, the Indus is not far. The river is wide enough to correct assumptions. To European eyes used to rainfall and reservoirs, a large river can look like proof that water is plentiful. In Ladakh, the river’s presence coexists with a different reality: usable water depends on access, timing, and the work of bringing it to the places where people actually live.

Walk in Shey or Thiksey and you can see the old logic of settlement. Fields are arranged in terraces where water can be guided by gravity. Lines of willows indicate channels that run even when the ground looks dry. The channels are narrow, cut into soil and stone, and they ask for constant attention. A small collapse can divert flow. A blocked inlet can starve a plot of barley. Water is not only a resource; it is a moving system with weak points.

In a modern street in Leh, the system’s weak points are different: broken valves, frozen sections, poor pressure, contested distribution, and the uneven pace of infrastructure. In a village, the weak points may be the same as they have always been: a cracked channel, a shift in snowmelt timing, an intake choked by sediment, a spring that runs lower than before.

Channels, pipes, and the short distance between them

In places like Nimmu or Basgo, where the landscape opens and the Indus valley widens, the line between old channel and new pipe can be traced in a short walk. You see the stonework of an older system, then the plastic fittings of a newer one, sometimes within the same field boundary. One does not replace the other cleanly. They overlap and they compete for the same water at different times.

What changes when the balance shifts is not only volume. It is predictability. A field can accept less water if it arrives on time. A household can manage a short supply window if it happens when someone is home. A system becomes fragile when timing becomes erratic—when the usual meltwater pulse is late, when cold snaps freeze what should have flowed, when a hot spell increases demand at the same moment a supply line weakens.

People do not always describe these changes in the language of climate. They describe them in the language of work: the number of trips, the minutes spent waiting, the amount of fuel used to melt ice, the day when a channel was dry when it should not have been.

One route, repeated: the domestic geography of containers

A jerrycan carries a story that a pipe hides. Its scratches show the ground it meets. Its handle shows the angle of a wrist. Its base shows how often it has been set down on stone. If you follow it, you learn the household’s map.

In Leh, the map can include a shared tap down the lane, a public standpost near a road, or a tanker stop announced by word and movement rather than by a sign. In villages nearer the fields, the map can include a channel junction or a spring outlet. The route is not heroic. It is repetitive. Its significance lies in how it pulls time out of a day that is already full of tasks.

In winter, when temperatures drop sharply, the route can change. A tap that works at midday may not work at dawn. A container left outside overnight may freeze in a way that makes it useless until it thaws. Some households keep a small reserve indoors, even if space is tight, because the alternative is to break ice at an outside point with a stick or a stone. Fuel is then part of the water story. Gas and firewood are used not only for cooking, but for turning ice into liquid.

The wait time is part of the supply

When a container is filled from a slow source, the time it takes becomes a real cost. A thin stream makes a simple act extend into a small vigil. A person stands with one hand on the container to keep it steady. The mouth is positioned carefully to prevent splashing. If the tap is shared, the pace of one person becomes the pace of everyone behind them.

On some days, the constraint is not a lack of water at the source but the flow rate and the queue. The scene can look ordinary—people in jackets, children shifting their weight, a dog circling the edge of the group—but the structure of the line tells you something: water is being rationed by time. Each container in the queue is a measurement, each person’s patience a component of the system.

At home, the kitchen receives this time-stretched water and treats it accordingly. Dishes are stacked to be washed in one session. Vegetables are cleaned over a basin so the rinse water can be used again for a second rinse or for cleaning a floor. A cup is wiped rather than rinsed. Soap is used in smaller quantities because it demands more water to remove.

“If the tap is weak, we fill less and we come again,” a woman in Leh told me, pointing to the handle marks on her container. “It is not one trip. It is the day.”

What sits above the kitchen: ice that sets the terms

In Ladakh, the word “glacier” can sit in the background of ordinary talk in the same way “electricity” does: present, essential, and often discussed only when it fails. The kitchen does not see ice directly, but it lives under its timing.

Drive out of Leh toward the mountains that frame the town and you pass gullies where meltwater runs for part of the year, then fades. Some flows are guided into channels. Others sink into gravel. Where ice and snow feed a stream reliably, a village can build around it. Where that feed weakens or becomes less predictable, everything downstream becomes more complicated: irrigation, drinking water, sanitation, and the simple act of washing hands.

In places such as Phyang, where an ice stupa has been built in winter months to store frozen water and release it in spring, the logic is clear even without slogans. If meltwater timing is changing, people look for ways to hold water in a form that can be released later. The ice is shaped and placed deliberately, like a seasonal tool.

The shift is often visible first in the fields

A kitchen can make do with less water for a short time. Fields are less forgiving. Along the Indus valley, the old channels that feed barley plots and vegetable gardens make changes observable. A channel that once carried water at a certain week of the year carries less. A small patch at the far end of a field browns earlier. Sowing schedules adjust. People talk about the day they opened a channel gate and the water arrived late, or arrived thin, or did not arrive at all.

These details do not require exaggeration. They are practical signals. A household notices them because households in Ladakh are usually tied to fields, animals, or both. Even in Leh, where livelihoods are more varied, many families maintain connections to villages and land. Water moves between domestic and agricultural use; priorities are negotiated across seasons and across households.

The Ladakh water crisis is not a single event. It is a set of small constraints accumulating: an irrigation turn shortened, a spring weaker, a line longer, a freezer-like night that freezes a pipe, a hotter day that increases demand, a repair delayed because the person who knows how to fix a valve is in another village.

Leh, tourism, and the mathematics of demand

European readers often arrive in Leh with a plan that fits neatly into days: a few nights here, a drive there, a monastery, a market, a pass. The town can make this easy. There are cafés, guesthouses, new hotels, and a sense of movement. But water does not always scale with this ease.

In peak season, the number of people using the same distribution system increases. This is not a moral argument; it is arithmetic. More showers, more laundry, more kitchens cooking for guests, more toilets flushing, more floors being cleaned. Even when guesthouses are careful, the baseline rises. The water supply becomes not only a household matter but a town-wide management problem.

In Leh, you can see evidence of this in small ways. New tanks appear on rooftops. Pipes are rerouted. A hose runs along a wall into a storage container. A hotel has a larger tank than a neighbouring house. A family adds another container to its stack because the supply window is less reliable during crowded months.

Practical travel habits that match the place

If you are visiting Ladakh, it is possible to move through Leh without noticing any of this, especially if you stay in a place with a large storage tank and a steady generator. But the town is not separate from the systems around it. A few habits align travel with reality without turning your trip into a lecture.

Ask your guesthouse how water is stored and when supply usually comes. Take shorter showers and do not request fresh towels daily. If laundry is offered, use it sparingly. Refill a water bottle rather than buying multiple small plastic bottles. These are ordinary actions, but in a place where water is handled as volume rather than as an endless stream, they matter in ways a visitor can understand immediately.

They also make you a quieter guest. In Leh, quiet is not only about sound. It is about how much you draw from systems that are already being negotiated by the people who live there year-round.

The point where the line breaks is rarely where the problem begins

A broken line in a kitchen is a visible failure: no water, a dry tap, a pipe that coughs air. The cause can be far away: a frozen segment, a valve upstream, a repair delayed, a supply diverted, a source running lower, a channel clogged. The kitchen is the end point where these chains become undeniable.

In Kargil, where the geography and climate differ from Leh but water management is still central, you see another version of the same principle: distribution depends on infrastructure and on maintenance. In Dras, where winters are severe, freezing is not an inconvenience but a defining condition. In the Zanskar region, around Padum and villages such as Zangla and Stongde, winter can shift routes and compress options. The details change, but the structure remains: water is a system with points of failure that can appear suddenly at the household level.

Repairs, know-how, and the limits of improvisation

When a line breaks, people do what people do: they improvise. A hose is attached. A bucket is moved. A neighbour shares. A child is sent to check a tap. But improvisation relies on a deeper layer of stability: someone who knows the system, access to parts, a shared agreement about timing and turns, and a source that can still supply enough water to make the effort worthwhile.

In some places, the most skilled knowledge is not written down. It sits with specific individuals: the person who understands which channel gate to open first, the person who can thaw a frozen line without cracking it, the person who knows where a leak usually forms. When those individuals are absent, sick, or occupied elsewhere, a small failure can last longer than it should.

This is not a romantic detail. It is a practical one. And it belongs in the same frame as larger discussions of climate and glaciers because systems do not fail only from physics. They fail from maintenance gaps, from unequal access, from the slow accumulation of small stresses that infrastructure and community have to absorb.

What remains after the day’s last pour

In the evening, the jerrycan returns to its place near the door. The kitchen surface is wiped. A kettle is filled enough for morning tea, not more. The basin is tipped outside. The last greywater darkens a patch of ground and disappears. In winter, it can freeze into a thin plate that will be broken the next day.

If the supply window was good, the house looks almost like any other. If it was poor, there are visible adjustments: fewer dishes washed, fewer clothes rinsed, a floor left for later, a bucket saved for the toilet. These are not dramatic choices. They are small reroutings of ordinary life.

Above Leh, above the villages in the Indus valley, above the routes toward Zanskar, the ice that feeds the system continues to set the terms, even when it is not visible from a kitchen window. The kitchen does not need to name the glacier to be governed by its timing. It simply counts what it has, measures what it uses, and arranges the day around what arrives.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.