Introduction – A Tale of Two Landscapes

From the Wind of the Andes to the Silence of the Himalayas

The first breath I took in Ladakh felt thinner than the air I remembered from Patagonia—but richer somehow, not in oxygen, but in meaning. I arrived in Leh on a sharp blue morning, the kind where the sky feels so close it’s like pressing your forehead against a quiet windowpane. The Himalayas did not roar the way the Andes do. They whispered. Their silence was not emptiness; it was presence. In Patagonia, the wind shouts. Here, in Ladakh, the stillness listens.

As a regenerative tourism consultant, I’ve spent years chasing landscapes that push against the edges of human habitability. Yet this was different. Ladakh’s altitudes sit not only above sea level, but somehow above time—floating in a thin realm where stone, sky, and soul negotiate their balance. From Torres del Paine’s granite towers to the vast openness of the Zanskar Valley, there’s a shared visual grammar: rugged silhouettes, shifting skies, and a certain sacred geometry only the mountains know.

But beneath that visual kinship lies a divergence. The Andes, especially Patagonia, carry an energy of resistance—winds that challenge, rivers that defy. The Himalayas, particularly in Ladakh, offer submission instead: to altitude, to weather, to spiritual silence. In Patagonia, the body learns to endure. In Ladakh, it learns to yield.

Why This Comparison Matters Now

Remote regions like Ladakh and Patagonia are no longer the isolated outposts of only the boldest travelers. They are now symbolic frontiers—measuring sticks for how tourism is changing in the face of climate urgency, cultural erosion, and rising global wanderlust. European visitors, increasingly aware of their environmental footprint, are asking harder questions: Where can I go that doesn’t destroy what I came to see? And just as importantly: Where can I go that transforms me, not just entertains me?

The truth is, Ladakh and Patagonia stand as natural mirrors—reflecting both the fragility of ecosystems and the resilience of traditional communities. Both demand something from the traveler: patience, respect, and above all, presence. And both offer something deeper than vistas: they offer a return to what we’ve forgotten.

In this series, I will explore Ladakh as seen through the prism of Patagonian experience: its nature, its culture, and the complex, hopeful path of eco-travel. For readers across Europe—those who’ve walked through Basque forests, sailed Norwegian fjords, or hiked the Dolomites—I invite you to look at Ladakh not as a distant frontier, but as a parallel echo of the landscapes you already hold dear.

Nature’s Architecture – Mountains, Sky, and Solitude

Landscapes That Redefine Human Scale

It’s easy to feel small in the face of the Andes. It’s inevitable in the Himalayas. In Patagonia, nature often arrives in motion—a gust, a storm, a condor riding thermals. In Ladakh, nature arrives in stillness. The mountains don’t move. They remain. And in their silent permanence, they dwarf not only the body but the ego.

Standing in the Nubra Valley, I found myself tracing the ridgelines with the same reverence I’d once reserved for the jagged skyline of the Fitz Roy range. But here the contours are smoother, older, more worn—like the bones of something wise. The air is thinner, and so are the sounds. There are no howling winds here, only the faint crackle of a prayer flag in the breeze.

Geologically, the Andes and Himalayas were both born of tectonic violence, yet their visual vocabularies are distinct. Patagonia’s sharp granite needles, such as those in the Southern Ice Field, feel like declarations. Ladakh’s rolling ranges—often braided with ancient glacial valleys—feel more like meditations. In both cases, however, you are confronted with scale. Not the kind you measure in meters, but in humility.

While hiking toward the base of Kongmaru La, a high pass in the Markha Valley, I watched a herd of bharal—Himalayan blue sheep—navigate the cliffs with the same lightness I’d seen in Patagonia’s guanacos. The echo was uncanny. Just as condors ruled the skies of Aysén, Ladakh belongs to the lammergeier, the bearded vulture. Different species, similar majesty.

Living in Extremes – How Climate Shapes Culture and Travel

Both Ladakh and Patagonia exist on the edge of what is survivable. With less than 100mm of annual rainfall in parts of Ladakh and persistent glacial retreat in southern Chile and Argentina, climate is not a backdrop—it’s a protagonist.

In Europe, we speak of weather as conversation. In these places, it’s a negotiation with life. The water table, the oxygen levels, the angle of the sun—each one determines how long a village can sustain itself, or whether a trekker will safely acclimatize. I’ve met Ladakhi farmers who speak of snowfall the way winemakers in the Loire speak of rainfall: intimately, anxiously, reverently.

As regenerative tourism gains momentum across Europe, the experiences of regions like Ladakh and Patagonia offer crucial lessons. These are not lands to be consumed—they are places that challenge the visitor to adapt, not the other way around. Their extreme climates are not obstacles; they are the essence of their resilience.

To witness a moonrise over Tso Moriri Lake or a sunrise over the Perito Moreno Glacier is to recognize that nature isn’t just beautiful—it’s instructive. The solitude of these high-altitude wildernesses teaches a language we’ve almost forgotten in our cities: the slow, sacred grammar of awe.

The Cultural Spine – Sacredness, Simplicity, and Survival

From Mapuche to Monasteries: Spiritual Grounding in Harsh Terrain

There is something remarkably similar in the way the Mapuche elders of southern Chile speak of the land and how Ladakhi monks speak of the mountains. In both cultures, the landscape is not a resource. It is not a view. It is a relative. A teacher. A presence.

In Patagonia, the concept of Itrofill Mongen—the interconnectedness of all living things—is woven into Mapuche cosmology. In Ladakh, this mirrors the Buddhist understanding of interdependence: the belief that nothing exists in isolation. The more I listened, the more I realized that these ideas are not philosophies. They are survival mechanisms dressed in spiritual language. When you live at 3,500 meters above sea level, your theology cannot be abstract. It must be useful.

I spent a morning sitting with a monk at the Hemis Monastery. He offered me butter tea, and we spoke of the river that flows past his home. He said he listens to it as one listens to a story—sometimes joyful, sometimes fierce. I remembered a similar moment along the Río Baker, where a Mapuche woman described the river’s moods as if describing a sibling. These are not metaphors. They are relationships.

For European travelers who often visit sacred sites as spectators, this presents an invitation: not to consume a culture, but to participate in its rhythm. Ladakh, like Patagonia, doesn’t perform its traditions for visitors. It lives them—quietly, unapologetically. The challenge is to be still enough to see it.

Hospitality in Harshness – A Shared Ethos of Generosity

The harsher the climate, the warmer the welcome. I have found this to be true in wind-lashed hamlets on the Patagonian steppe and in sunburnt villages tucked into Ladakh’s mountain folds. In both places, hospitality is not a transaction—it’s an ethic.

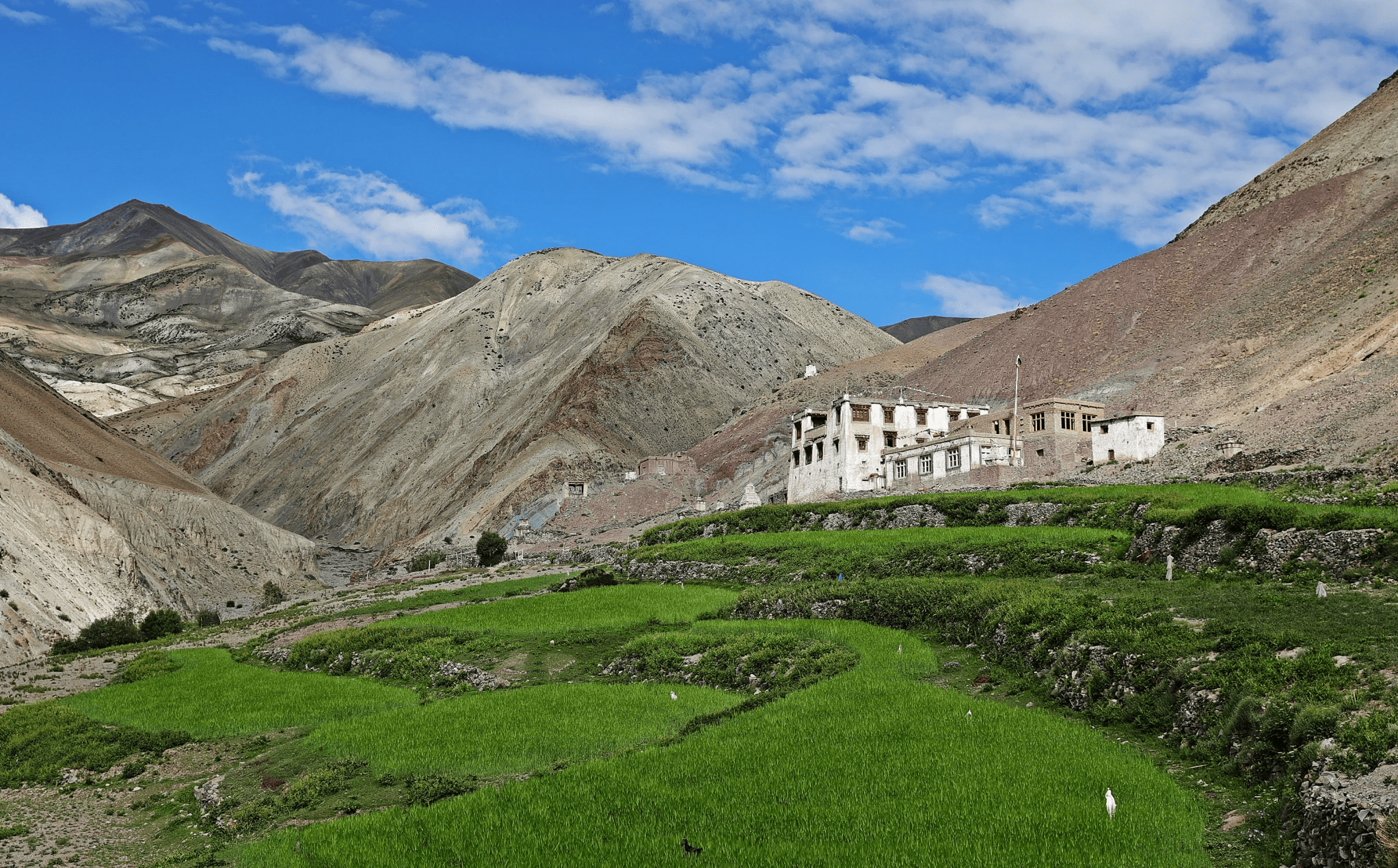

In Patagonia, I was offered shelter by a gaucho who lived three days from the nearest road. In Ladakh, I was welcomed into a family home in the village of Rumbak, where the matriarch insisted I take the warmest blankets, even though the night fell below freezing. These gestures are not rare. They are routine. And they tell us something about what community means when the land offers no shortcuts.

Homestays in Ladakh, much like estancias in Patagonia, provide more than accommodation. They offer a doorway into another pace of life, one ruled by seasons, livestock, and shared labor. You wake to the sound of barley being milled, not traffic. You eat what the earth provides—root vegetables, dried fruits, salted butter. The pace is deliberate, and so is the care.

For visitors from Europe, where travel often leans toward convenience, this can be both a culture shock and a revelation. Here, you are not a customer. You are a guest. And that distinction changes everything. It slows you down. It softens you. It reminds you that in the most demanding places, generosity is not optional—it’s survival.

The Cost of Discovery – Eco-Travel or Eco-Impact?

The Boom of Conscious Travelers

In recent years, a subtle shift has taken place in the European travel psyche. We are no longer content to simply go somewhere “beautiful.” Increasingly, we want to go somewhere meaningful. With that desire comes a reckoning: can our journeys heal, rather than harm? This question echoes loudly in places like Ladakh and Patagonia—regions once shielded by remoteness, now exposed to the surging currents of global tourism.

Both regions have seen visitor numbers climb steadily. In the decade prior to the pandemic, trekking permits in Ladakh more than doubled. Meanwhile, Patagonia’s Torres del Paine welcomed over 250,000 tourists annually, placing immense pressure on its fragile trails and glacial ecosystems. These numbers reflect a hunger for wildness—but they also reveal a paradox: the more we seek solitude and purity, the more we risk disturbing it.

In my work, I’ve spoken with local guides in Leh and Puerto Natales who express both gratitude and concern. Tourism brings income, yes—but also plastic waste, cultural dilution, and shifting values. When the economy becomes dependent on visitors, the soul of a place can begin to erode.

And yet, there’s hope. Many of today’s travelers—especially from Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Scandinavia—arrive in Ladakh asking thoughtful questions. They seek homestays, not hotels. They want slow treks, not fast itineraries. They ask about offsetting their carbon footprints, about volunteering, about supporting local cooperatives. These are not trends. They are signals of a new kind of traveler: one who understands that the journey itself must be regenerative.

What Patagonia Taught Me About Preservation

In southern Chile, I walked part of the Route of Parks—a conservation corridor stretching 2,800 kilometers through national parks and protected areas. Spearheaded by Tompkins Conservation, it’s a bold example of what happens when private initiative and public will unite around preservation. Trails are clearly marked. Visitor education is built into the infrastructure. Tourism is treated not as an entitlement, but as a privilege.

Ladakh stands at a similar crossroads. Its terrain is just as majestic. Its people, just as rooted. But the pressure here is different. Infrastructure is developing quickly, sometimes recklessly. Tour buses now enter villages that once welcomed only pilgrims or herders. Plastics accumulate along sacred rivers. Altitude sickness is treated casually by visitors who don’t pause to acclimatize, putting both themselves and local resources at risk.

But the tools of protection are available. Zoning restrictions, community-based tourism, guide cooperatives, and educational signage are not distant ideals—they are practical mechanisms already working elsewhere. If Ladakh looks to Patagonia not just as a fellow wild region, but as a mentor, it can avoid many of the growing pains that have already tested South America’s southern frontier.

The lesson is clear: wild beauty must be curated, not consumed. Without limits, even the most mindful traveler becomes an unwitting agent of erosion. But with vision and care, eco-travel can become a force of protection—a way to leave places better than we found them.

The Future Is Now – Regenerating What We Visit

Beyond Sustainability: A Regenerative Model for Ladakh

In Europe, we often speak of sustainability as the goal. But after spending time in Ladakh, I’ve come to believe that mere sustainability is no longer enough. We must move toward regeneration. In Patagonia, this idea is gaining traction through rewilding programs, native species restoration, and park management that goes beyond preservation to active revival. Ladakh, though just beginning its tourism transformation, has the chance to leap directly into a regenerative framework—before the damage sets in.

But what does regenerative tourism mean here, in this land of sky and stone? It means designing journeys that heal—both for the land and the people. It means encouraging travelers to walk, not drive; to stay longer, not rush through; to learn from locals, not instruct them. It means limiting visitor numbers in sensitive areas like Tso Moriri, Zanskar, and Nubra Valley—places already straining under seasonal peaks.

The building blocks already exist. Ladakh’s traditional knowledge systems, from water channeling (the zings) to sustainable architecture (rammed earth houses), are rooted in regenerative principles. What is needed is a way to integrate these practices into the travel economy. This is where policy must meet philosophy—where local governance, tourism operators, and travelers align around a shared ethic: give more than you take.

In the Netherlands, where I grew up, we have mastered efficiency. In Peru, where I now live, we are rediscovering ancient regenerative methods. Ladakh stands poised between these worlds—technologically curious, culturally rich, and environmentally vulnerable. It is a place where regenerative travel could become more than a theory. It could become the template.

The Role of the Traveler: Witness, Not Consumer

As I stood near Stok Kangri at sunrise, my boots planted in the frost-crusted sand, I thought of how often we mistake travel for possession. We collect places like trophies, catalog moments for Instagram, rush toward summits only to descend with barely a breath of awareness. But Ladakh teaches something else. It teaches us how to be a witness.

To witness means to arrive without conquest. To listen without assuming. To see a village and not wonder how to photograph it, but how to respect it. In the regenerative model, the traveler becomes a partner in protection—not an intruder, but a participant in the stewardship of landscape and culture.

European travelers—especially those already seeking meaning over milestones—have a unique role to play. Your decisions matter. The choice to travel off-season. The choice to support a homestay. The choice to walk, to ask, to slow down. These choices don’t just improve your journey; they strengthen the very places you came to admire.

Ladakh does not need to become the next overdeveloped destination. It can become the first regeneratively guided high-altitude region in South Asia. But only if we all choose presence over pressure, and care over consumption. That choice begins not in government halls, but in the heart of each traveler.

Conclusion – When the Winds Speak the Same Language

The Sacred in Two Hemispheres

As I prepare to leave Ladakh, I find myself returning to the wind. It’s quieter here than in Patagonia, but no less expressive. In both places, the wind is not merely a weather pattern—it is a messenger. In Patagonia, it roars across the plains with the urgency of survival. In Ladakh, it whispers between stupas and stones, carrying the hush of centuries.

Though separated by continents, these two high-altitude worlds speak the same elemental language. They speak in silence, in scale, in sacredness. They remind us that there are still places on this earth where the land holds authority, where the traveler must listen before acting, and where beauty exists not for our consumption, but for our contemplation.

I think often about the Europeans I’ve met on these journeys—those who traveled not to conquer but to connect. A Belgian woman who hiked the Markha Valley and cried at the sight of a Ladakhi grandmother tending a barley field. A Dutch couple who skipped the highlights and instead spent two weeks helping a community install solar lights. These are the new pilgrims—not to temples or cathedrals, but to landscapes where the divine is written in rock and snow.

To those reading this from Berlin or Bergen, from Barcelona or Brussels: know that your choices as a traveler have power. Ladakh is not just another destination. It is a test—of our restraint, our awareness, our humility. It asks something rare of us: to receive without taking, to witness without altering, to journey not outward, but inward.

And so, as the wind of Ladakh brushes past my tent for the last time, I carry its stillness with me—the same way I carry the howl of Patagonia. Two winds. Two worlds. One shared truth: the earth is not ours to use, but to belong to.

About the Author

Originally from Utrecht, the Netherlands, Isla Van Doren is a regenerative tourism consultant with over a decade of experience working across diverse ecological landscapes—from the windswept steppes of Patagonia to the cloud forests of the Peruvian Andes, where she now resides just outside Cusco.

At 35, she brings a unique voice to the world of sustainable travel—one that blends academic depth with poetic sensibility. Her writing is known for weaving together statistical insight, ecological reflection, and emotional resonance, inviting readers into a slower, more conscious relationship with the places they explore.

Isla’s first journey to Ladakh marked a turning point. Viewing the Himalayas through the lens of her Patagonian experience, she draws sharp, analytical parallels between remote regions, challenging conventional narratives of tourism. Her work encourages travelers to become not just visitors, but caretakers of the landscapes they enter.

Through storytelling, consulting, and field-based collaboration, she advocates for a future in which travel regenerates rather than depletes. She writes to reconnect us—not only with nature, but with the responsibility that comes with witnessing its beauty.