In Ladakh, the Ground Has a Vocabulary

By Sidonie Morel

The First Glitter: A Small Museum, a Big Country of Rock

A room of specimens, and the habit it teaches

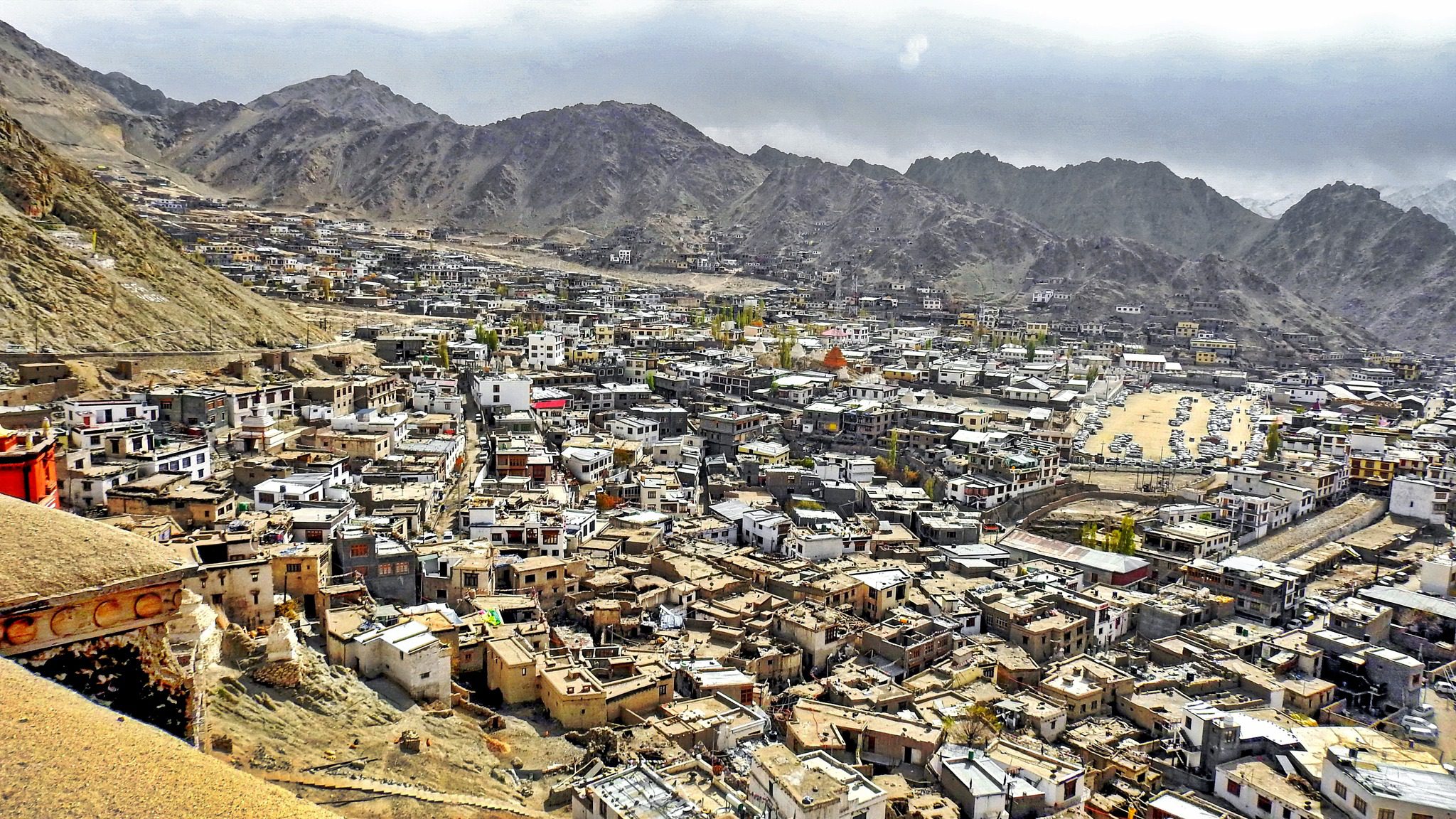

In Leh, the roads are busy with ordinary errands—fuel, vegetables, a packet of biscuits pressed into a coat pocket—yet the town also has a quieter invitation: to look down and take the ground seriously. A modest rocks and minerals collection does this without ceremony. You enter expecting labels and glass. You leave with a changed sense of scale.

Inside, the specimens are not trying to impress you with drama. They sit with the steadiness of things that do not need to move for centuries. There are stones that catch light and stones that swallow it. Some look like they were cut from a single thought—clean planes, crisp edges. Others are mottled, layered, full of small interruptions: lines that suggest pressure, heat, fracture, and long pause. If you have come to Ladakh for its wide views, the museum asks you to consider another kind of vista: not horizon, but interior.

What you notice first is weight, even behind glass. A piece of ore does not shine the way a souvenir does; it holds a darker glint, as if the light has to negotiate to get out again. A pale stone, when you look closely, is rarely plain. It is grain and sparkle and faint clouding, a gathering of minerals that have learned to live together. Some specimens read like a local archive: the mountains above, the river valleys below, and the invisible history that joins them.

The labels matter, but not in the way visitors expect. Names—granite, basalt, quartz—are useful, and so are the more specific words that start to appear once your eye sharpens. Yet the stronger lesson is that Ladakh is not only a landscape but a material. The mountains are made, and the making is still present in what you can hold in your palm: a pebble on a track, a vein of lighter stone in a dark wall, a dust that settles on your lips after a walk.

How to visit without turning it into a checklist

This is not a place that demands long study, and that is part of its charm. Twenty minutes can be enough to begin; an hour can change what you notice for days. If you are planning your time in Leh, it slips easily into a morning between breakfast and whatever you have arranged next. You do not need equipment, and you do not need to pretend to be a geologist. What helps is to arrive with clean hands and slow attention. Touch the railing if you like, read a few labels, then step back and let the surfaces do their work.

When you leave, do not rush to photograph everything. Instead, look at your own shoes. Look at the dust on the hem of your trousers. Notice the fine grit at the edge of the street where wind collects it. The museum’s real gift is not what it contains, but what it sends you back into town prepared to see.

Leh’s Dust, the River’s Edge, and the Habit of Looking Down

The pebble underfoot as a local alphabet

In Ladakh, the ground is rarely silent. It crunches, it shifts, it clicks under your soles. In Leh’s lanes the surface changes quickly—packed earth, broken tarmac, a scatter of small stones dropped from a truck, a patch of smoother dust where a broom has been through. The air is dry enough that fine particles cling to skin and fabric without needing moisture. Your fingers learn the difference between powder and grit. Your tongue learns it too, if the wind rises.

Walk even a short distance and you begin to recognise patterns. A wall built from local stone is not a neutral boundary; it carries a colour range, a texture, a sort of practical honesty. Pale stones tend to show their grain when the sun is low. Darker stones keep their cool longer in shade. In courtyards, stones become furniture: a step worn in the middle, a threshold polished by years of sandals, a flat rock used as a seat because it is there and it is reliable.

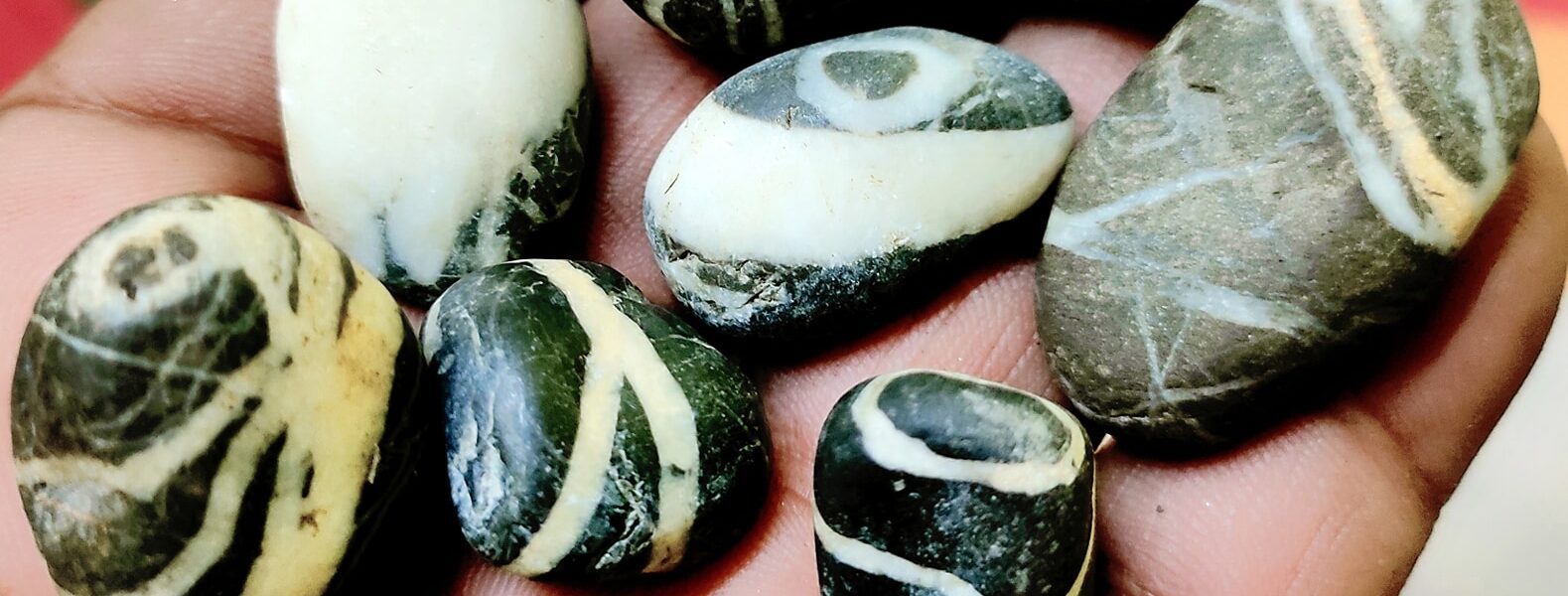

Along the river valleys outside town, the scale shifts again. Water sorts material with a blunt patience. You see beds of rounded stones, some smooth as if they have been handled for a long time, others still angular, recently arrived from higher slopes. The river makes a language of size and weight: what can be moved in flood, what can only be nudged, what stays put. In Ladakh’s high cold desert, where water is both precious and forceful, the river’s work is visible in the simplest way: in the shapes it leaves behind.

It is tempting to turn this into symbolism. Better to keep it practical. When you walk near a stream or across a stony track, you feel how unstable some surfaces are. You notice how a single loose rock can change your balance. You understand why local steps are placed where they are, why paths bend, why a route that looks direct on a map often chooses a more sensible line on the ground. Geology, here, is not a lecture. It is a daily negotiation between body and surface.

Small observations that travel well

European readers often arrive in Ladakh with a habit of looking up—toward peaks, sky, distance. Keep that habit, but add another one. Each day, choose a small object and let it hold your attention for a minute. A pebble with a pale streak. A dark stone with a metallic glimmer. A sliver of rock that looks like it wants to split along its own line. Do not take it; you do not need to collect to learn. Hold it briefly, feel its temperature, then put it back where it belongs.

Later, when you sit down to eat, notice the stone floor under a table, the weight of a bowl, the way a kettle sits on a stove. Ladakh’s material world is coherent. The same dryness that cracks lips also preserves sharp edges on rock. The same sunlight that bleaches fabric also makes mineral grains visible. These are not grand insights. They are small truths that make a place feel specific, and they are the kind that remain after you leave.

Jewels of the Mountains: When Geology Turns Personal

What “treasure” looks like without romance

In markets, jewellery is often presented as pure ornament. In Ladakh, it is hard to keep it that simple. Metal and stone are part of the region’s visual life—turquoise tones against skin and wool, coral red set into older forms, beads that carry both beauty and meaning. Yet behind the display is something more literal: the fact that minerals are the raw material of such objects, and that the mountains are not only scenery but source.

Look closely at a piece of jewellery in a shop window and you can sometimes see the difference between polish and substance. A stone that has been cut might be perfectly shaped, but it still carries its internal character: slight variation in colour, a clouding, a vein. The surface is new; the material is old. This is not sentiment. It is simply what minerals are—structures formed under conditions that do not resemble human time.

In Ladakh, where the ground is often bare and the air has little softness, the attraction of small bright objects feels practical rather than indulgent. A bead catches light and signals presence. A metal clasp holds. A stone set into a piece of silver has weight; you feel it when you lift it, when it presses into fabric, when it warms slightly against skin. Such details remind you that adornment can be physical in a straightforward way—texture, heft, temperature—rather than only symbolic.

From a museum label to a market counter

After you have spent time with mineral specimens, the market becomes more interesting, and also more complicated. You begin to understand that a stone is not only a colour but a structure. You may find yourself asking different questions: not “Is this pretty?” but “Where did this come from?” and “How was it treated?” In a region where tourism is present and trade is active, such questions are not accusations; they are a way of paying attention.

If you are curious, be polite and specific. Ask about local craft and local supply without assuming a single story. Some objects are made in Ladakh; others come through long networks of trade. Some stones have local associations; others are chosen because they suit a design. As a visitor, you do not need to solve the entire chain. What matters is that you recognise materials as real things, not merely as pattern or colour.

In travel writing, it is easy to treat gemstones and minerals as shorthand for luxury or for tradition. In Ladakh, they can be treated more plainly: as part of the region’s material culture, shaped by availability, skill, and taste. This is a more respectful approach, and it also produces better detail. You write what you can see: the way a stone reflects sunlight at a certain angle, the way silver darkens in a seam, the way a bead sits against wool. The reader can do the rest.

Lamayuru’s Soft Stones and Their Slow Collapse

Moonland, not moon: erosion you can touch

Lamayuru is often approached as a visual spectacle: pale ridges and gullies that resemble a miniature badlands, a landscape people call “moon-like” because it looks unfamiliar. The description is useful for first impressions, but it can also distract. The ground there is not alien. It is simply exposed, soft in places, and actively being shaped by wind and water.

If you stand still for a moment, you can watch how the surface behaves. Fine grains slide under the smallest pressure. A slope holds until it doesn’t; a shallow ridge loses a few particles with a breath of wind. The colour variation is subtle—off-white, grey, a hint of tan—and in strong sun it can look flat. But as the light shifts, you begin to see texture: layered deposits, small collapses, the ridged pattern left by water that once moved differently than it does now.

The ground feels dry, yet it does not feel inert. Step carefully and you can sense how easily the surface breaks. The sound of your footsteps changes from firm crunch to a softer crumble. Dust rises in a thin veil and settles quickly, because the air does not hold it long. If you touch a rock, your fingertips return with a pale coating, as if you have handled flour. This is what makes the place memorable: not only the view, but the material response—how it yields, how it stains, how it records contact.

Practical details that matter more than drama

Lamayuru’s landscape encourages wandering, but the ground’s fragility asks for restraint. Choose your footing with care. The edges of paths can be unstable, and the fine sediment can hide small drops. Good shoes are not a performance detail here; they are a way of reducing risk. If you travel with children or older companions, keep them close when you step off the most obvious track.

It is also worth remembering that this landscape is not a theme park. It is part of a living region, with monasteries, villages, and routes used for practical travel. Treat the terrain with the same ordinary respect you would give to a fragile historical site: do not climb where it is clearly eroding, do not carve names, do not treat collapse as entertainment. The reward is that you can stay long enough to notice subtler changes: how shadow makes small ridges visible, how the colour warms at dusk, how the wind draws a thin line of dust along the base of a slope.

For a reader, these details carry more weight than superlatives. They make the scene plausible. They also connect back to the broader theme of Ladakh’s minerals and sediments: that the land is not only monumental rock, but also the softer materials that fill valleys and shape routes, the deposits that can be moved by a single season of water.

Puga Valley: Sulfur Breath, Warm Ground, and the Minerals That Bloom From Heat

Where the earth shows its work at the surface

Puga is one of those places where the ground refuses to behave like background. You notice it first through change: a faint smell in the air that lingers in cloth, warmer patches of earth, a dampness where you would not expect it. Even if you do not name the chemistry, you recognise the signs of geothermal activity—steam, mud, and mineral-stained surfaces.

The textures are specific. Mud is not simply mud; it has thickness and sheen, and it dries at the edges into crust. A pale deposit can form a thin layer like icing, and when it breaks it reveals a different colour beneath. In some spots, the ground looks lightly dusted, as if a small snowfall has settled and then decided not to melt. In others, darker dampness creates a heavy contrast against the surrounding dryness. The air can carry a sulfur note that feels clean and sharp rather than perfumed. It is a scent that announces itself and then becomes part of your awareness, like smoke on a jacket after a fire.

Here, minerals are not only a museum story. They appear as active deposits—crusts, stains, and salts that form through heat and evaporation. If you have read about borax and other evaporite minerals, the words feel less abstract when you see a pale crust at the edge of a wet patch, or when you notice how mineral deposits create a slightly different sound underfoot: a brittle crackle rather than a dull thud.

When “resource” meets “place” in the same sentence

Puga is often discussed in terms that belong to energy and extraction, because geothermal zones invite that vocabulary. The difficulty, as a visitor, is that “resource” language flattens what you can observe. It turns living ground into a category. A travel column has a different duty: to describe what is present without forcing it into a moral or a slogan.

What is present is clear enough. The valley holds warmth in a cold region. It holds mineral deposits where evaporation concentrates dissolved material. It holds a smell that marks chemical activity. It also holds animals and people moving through an open landscape—routes, grazing, pauses. The question is not whether this is “good” or “bad” in a neat sense. The question is what it looks like, what it does to fabric and skin, what it does to a boot sole, how it changes the colour of earth and the behaviour of water.

For European readers used to spa towns where hot water is channelled into tiled pools, Puga can feel rough and direct. There are no polished edges. The ground is the container. This rawness makes practical caution necessary. Watch where you step. Do not assume that every surface is stable. Keep a little distance from active vents and wet patches. The place does not need you to test it. It is already at work.

And if you want to carry something away from Puga, let it be the most ordinary evidence: the scent on your scarf, the pale dust that finds your cuffs, the memory of warmth under your palm when you touch a stone that has been heated from below.

A Piece of Ocean Lifted Into the Air, and Granite That Holds Its Ground

Ophiolite country and the dark gleam of ore

There are parts of Ladakh where the rocks tell an improbable story with complete calm: that material formed in an oceanic setting can be found far above sea level. Even if you do not use the technical term in conversation, the idea matters because it changes the emotional geography of the region. The mountains are not only “old”; they are assembled. They contain fragments that belonged elsewhere.

In areas associated with ophiolite belts and mineralised zones, the ground can look harsher—darker rocks, sharp fragments, occasional surfaces with a subtle metallic glint. This is where words like chromite and ore enter the conversation, not as romance but as material fact. A piece of ore does not behave like a decorative stone. It sits heavy in the hand. It can look almost black until light strikes it and reveals a controlled shine.

It is easy to sensationalise such places. Better to stay with what a traveller can responsibly observe. You may see rocks that appear unusually dark or dense compared with the pale, dusty surfaces that dominate many valleys. You may notice how certain stones resist weathering and keep their edges. You may find that the colour palette shifts—less beige, more charcoal, more greenish undertones in some rocks, more abrupt contrast where veins cut through a host stone. Such observations are enough to suggest complexity without pretending to be a field report.

If you are travelling by road, these zones can be passed quickly, and that speed is often the enemy of noticing. Ask your driver for a short stop where it is safe. Step out, breathe, and look at the ground for two minutes. Your hands will learn something your camera might not: the difference between stones that crumble and stones that resist, between surfaces that feel chalky and surfaces that feel hard and close-grained.

The batholith and the domestic life of stone

Then, elsewhere, Ladakh offers another kind of solidity: granite and related rocks that show themselves in building stone and in the big structural presence of the mountains. Granite is often treated as a single idea—hard, pale, durable—but in Ladakh it shows variation. Some surfaces are coarse enough that you can see individual grains. Others look more even, but still reveal themselves under angled light: tiny points, small flecks, a faint sparkle that appears and disappears as you move.

The practical consequence is visible in architecture. In villages and in parts of Leh, stone is not a decorative veneer; it is a working material. It becomes walls, steps, thresholds, and low boundaries that shape daily movement. A stone step can be worn in the centre where feet pass most often. A wall can be slightly darker near the base where dust and occasional moisture settle. A flat stone can be chosen for a cooking area because it holds heat differently, or because it is simply the right shape and weight.

For a reader, this is where “minerals” become intimate without turning sentimental. The material of the mountains enters kitchens and courtyards. It becomes part of the rhythm of a morning: a kettle set down, a bowl placed on a stone ledge, a hand resting briefly on a cool surface. You may not know whether a particular stone carries magnetite or other iron-bearing minerals, and you do not need to. What matters is that the stone behaves in ways you can notice—cooling, warming, resisting, staining—because those behaviours shape how people live with it.

Travel in Ladakh often encourages a hunger for big views and grand routes. The mineral journey runs alongside that hunger but asks for another attention: the small view, the held object, the grain under your fingertip. If you have spent time with a museum case, a market counter, an eroding ridge, and a warm mineral crust in a geothermal valley, you begin to understand the title phrase “Stones That Remember” in a practical way. Stones remember because they keep their structure. They keep their marks. They keep their weight. They do this without announcement, and that quiet persistence is one of the most reliable things a traveller can learn from Ladakh’s high cold desert.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.