Whispers of Resilience: Ladakh Cultural Preservation – Explore the enduring traditions and innovative practices in Ladakh that sustain its rich heritage amidst modern challenges.

Nestled between the icy embrace of the Karakoram range and the sprawling majesty of the Himalayas lies Ladakh—a land of rugged splendor where the relentless advance of global consumerism is making its mark. Nicola Graydon delves into the profound struggle of the locals as they strive to protect their cherished heritage.

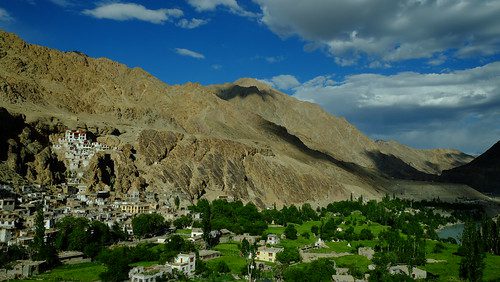

Likir, a serene village a mere three-hour drive west of Leh, embodies a scene of almost surreal beauty. Perched at an altitude of 3,500 meters, it unfurls like a lush sanctuary, contrasting sharply with the stark, snow-clad peaks above. The village, layered across three tiers, reveals the tireless efforts of human hands coaxing life from a desert landscape as thin and unyielding as the frigid mountain air. Streams, channeled through stone pathways, weave their way through vegetable patches, orchards, livestock pens, and sprawling terraced barley fields, bordered by graceful poplars and willows.

Once, during the brief summer months, these fields resonated with the joyous voices of villagers celebrating the bounty of their labor. Now, they are enveloped in silence.

‘The youth have all left,’ laments Dorjey Lundup. At seventy years old, he represents the seventh generation of his family to inhabit their ancestral home—a stately, three-story structure adorned with tattered prayer flags, giving it the appearance of a grand vessel adrift on a sea of greenery. Lundup, the venerable aba-le (father) of the household, is not only a skilled carpenter who crafted a wooden throne for a recent Dalai Lama visit but also an amchi, a traditional healer, and an accomplished chef. His humor is infectious, yet a somber tone overtakes him as he reflects on the changes he has witnessed.

‘Our young men enlist in the army, our children attend school. Others have ventured to the cities for government jobs,’ he says, twirling the small, hand-carved prayer wheel resting on his shoulder. ‘You cannot fathom how generous Ladakhis once were,’ he continues. ‘Everything was shared. Neighbors and friends always lent a hand during harvest time. Now, it’s all about money. Generosity has become a rarity. We are losing the essence of what it means to be Ladakhi.’

For days, I have been a guest in Lundup’s home, immersed in the Farm Project initiated by the International Society for Ecology and Culture (ISEC). This organization champions local alternatives to the pervasive global consumer culture. By engaging with the fields and living with local families, participants in ISEC’s program help elevate the status of farming and rural life in Ladakh, which has been increasingly undermined by misguided notions of modernity. Since its inception eight years ago, the sight of privileged Westerners willingly getting their hands dirty—enjoying tasks like tending to animals or churning butter in simple wooden churns—has rekindled respect among many young Ladakhis for their agricultural traditions.

A Himalayan Eden

Ladakh, nestled in the northeastern corner of India-administered Kashmir, was once a hidden gem to the outside world. Helena Norberg-Hodge, the founder and director of ISEC, was among the first Westerners to visit in recent times. She was struck by the region’s astonishing self-sufficiency. In one of the harshest environments known to man, people not only met their basic needs but also produced surplus grain, trading it for luxury items from beyond their borders. ‘They had developed social structures that maximized their limited resources. Their lives were physically demanding, yet they worked far fewer hours than we do in the West. Different faiths—Buddhists, Christians, and Muslims—coexisted peacefully for generations. Most importantly, they seemed genuinely content,’ Norberg-Hodge recalls.

A linguist by training, Norberg-Hodge quickly mastered the Ladakhi language and was uniquely positioned to observe the global economy’s impact on traditional culture. ‘The disparity between rich and poor widened dramatically,’ she notes. ‘What was once a land free of poverty suddenly faced unemployment, rising corruption, and crime. Families and communities began to disintegrate, becoming detached from their heritage and the land.’ For the first time in 500 years, there was unrest between Buddhists and Muslims.

In the more isolated villages, the traditional agricultural economy endures, but closer to the roads linking Leh with the Indian plains, the story is different. Imported subsidized rice, sugar, wheat, and other staples—transported over the Himalayas at great expense—are disrupting traditional diets and, more critically, undercutting local produce. Imported wheat flour, for instance, is sold at half the price of local flour, jeopardizing local farmers’ livelihoods.

One might wonder why such a wonderful culture could be so easily undermined. Norberg-Hodge attributes it to the psychological pressures to modernize, which eroded Ladakhis’ self-esteem. ‘I witnessed how people who had once been confident and proud began to view themselves as backward and inferior,’ she says.

‘I remember being guided around the remote village of Hemis Shukpachan by a young Ladakhi named Tsewang. I was struck by the beauty of the houses and asked him where the poor people lived. He seemed puzzled, then said, “We don’t have any poor people here.” Eight years later, I overheard Tsewang telling tourists, “If only you could help us Ladakhis, we’re so poor.”’

The advent of media and advertising introduced an idealized image of Western consumer culture. This portrayal of boundless wealth and leisure was further reinforced by the influx of Western tourists, many of whom spent upwards of $100 a day—comparable to tens of thousands of dollars in Europe or North America.

These illusions of modernity profoundly affected Ladakhis, particularly the youth, who had yet to solidify their cultural identities. Compared to the images of Paris and New York, their own lives seemed primitive and inadequate. Young boys aspired to be like Rambo; girls, to resemble Barbie.

‘Ladakhis began to adopt some of the neuroses common in the West,’ says Norberg-Hodge. ‘They even started using a skin-lightening cream called ‘Fair and Lovely.’

‘Daily, “experts” on the radio extolled the virtues of chemical fertilizers, caesarean births, and consumerism. There was no element of traditional culture to alert Ladakhis that they were being sold a false promise.’

Market Forces Conquer Shangri-La

In the fading light of a Friday afternoon in Likir, Tsering Lundup, a man of 45 years and the headmaster of a school several kilometers away, dashes up the rickety wooden stairs of his ancestral home. He arrives in the kitchen, resplendent in a suit and tie, momentarily exchanges pleasantries with his parents, and then vanishes, only to reappear clad in a traditional jacket, brandishing six rough-hewn scythes. His intent: to venture to the family’s distant fields, where Nepali laborers, enlisted to substitute for absent kin, are busy harvesting alfalfa.

As we traverse the streams—alternately gushing and dry, dictated by the fickle rhythms of irrigation that lend Likir its perpetually dynamic essence—Tsering reflects on his situation with a sigh. “Sometimes I wonder if I should abandon my job,” he muses. “Here I am, a headmaster by day, funding others to do what I myself yearn to do. My role holds value, but doesn’t it all seem a bit absurd?”

It felt awkward to suggest that Tsering Lundup was merely a casualty of ‘progress’; that the Ladakh of his youth—a place once lauded as the ‘last Shangri-La’ in the National Geographic of the 1970s—had been overtaken not by an army but by the relentless tides of market forces. His family, once the custodians of a timeless tradition, now found themselves ensnared by the inexorable march of globalization.

However, when I visited Tsering’s new residence on the outskirts of Leh, the contrast was stark. He now resides in a government ‘housing colony,’ a sprawl of gray concrete buildings that starkly contrasts with traditional Ladakhi architecture. This bleak, desolate environment, where grass struggles to break through cracked pavements and diesel fumes mingle with the stench of refuse, painted a disheartening picture. The vitality of the mountain air was replaced by the mechanical droning of trucks and the acrid smell of exhaust. This was a transformation so profound that it would have been unrecognizable to anyone familiar with the region a mere decade ago.

Yet, Tsering Lundup and his family navigate this soulless expanse with remarkable resilience, embodying the enduring spirit of Ladakh. To me, this place, barren and spiritless, was a harbinger of the grim fate befalling the once-vibrant Ladakh.

Seeds of Resistance

Curiously, Helena Norberg-Hodge, the driving force behind the Ladakh Project, harbors a more optimistic perspective. Faced with the encroaching threat of globalization, she spearheaded a movement to counterbalance it. The strategy revolved around offering the Ladakhis a clearer picture of Western life’s harsh realities.

In 1980, Norberg-Hodge and her husband, John Page, established the Ladakh Project, a modest British NGO. This was succeeded by the locally-managed Ladakh Ecological Development Group (LEDG) in 1984, aimed at countering the petroleum-centric development policies championed by the Indian authorities. Drawing upon local sustainability traditions, LEDG introduced a spectrum of appropriate technologies—solar heaters, small-scale hydroelectric units, and winter greenhouses.

Though slightly weathered by time, the LEDG’s Ecology Centre on Leh’s northern edge remains a brilliant testament to the harmonious integration of tradition and modernity. Its traditional architecture houses solar heating systems and a small wind generator. In its garden, solar cookers and greenhouses coexist with an extensive library covering topics from Ladakhi folklore to alternative technologies and Gandhian philosophy.

The impact of LEDG’s initiatives extends far beyond Leh’s boundaries. According to Sonam Dawa, LEDG’s director, Zanskar, a remote valley to the south, now enjoys round-the-clock electricity thanks to micro-hydro installations. “People are realizing they can’t rely on inefficient diesel-powered electricity. When it fails, it takes months to fix,” says Dawa. The LEDG’s current project involves installing an 80-kilowatt station to replace a diesel one, providing continuous power to 1,000 homes, and distributing solar cookers to half of these households.

Leading by Example

Unsurprisingly, LEDG has become a model for grassroots organizations globally. Delegates from NGOs across China, Peru, Bhutan, and other nations have come to Ladakh to glean insights from its success.

Thupstan Chhewang, another founding member of LEDG, now serves as the executive director of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC)—dubbed the ‘first Green Party of the East’ for its ambitious vision of a self-sustaining Ladakh and its nuanced grasp of globalization’s challenges. “Our goal is to eliminate diesel use by 2020,” Chhewang asserts. “With Indian government support, we are confident we will succeed.”

Chhewang, like Dorjey Lundup, is concerned about the impact of development on Ladakhi youth but believes that circumstances will ultimately draw them back to their roots. “We have a generation being educated for non-existent government jobs. They will return to our traditional resources and the fields,” he predicts.

Among LAHDC’s initiatives is the promotion of sea buckthorn—a hardy berry thriving in Ladakh’s arid soil. Used medicinally and rich in vitamin C and antioxidants, sea buckthorn could become a major organic export. “China produces 200 products from sea buckthorn,” Chhewang notes. “With sustainable propagation, it could be a significant revenue source without severing our cultural ties. Our climate positions us as a potential hub for organic seed production for India.”

Engaging with a government representative like Chhewang, who holds such progressive ideas, is unusual. The LAHDC still faces challenges in proving its efficacy. For now, the focus is on reforming education policies to make Ladakhi language compulsory and adjusting school terms to align with harvest periods. Chhewang candidly acknowledges the difficulties of political change. “We need to bring everyone, including bureaucrats, on board.” Yet, he unequivocally values the impact of ISEC’s work. “Helena was a pioneer in promoting alternative ideas. She stood alone in a time when development was idolized, advocating for the respect of our culture and suitable technology for our land. Her influence has been profound.”

The Echoes of Decline and the Dawn of Revival

On the edge of Leh, where the rhythm of the bazaar—a cacophony of internet cafes, trinket stalls, and ceaseless honking—gradually gives way to the barren, windswept plains, lies the headquarters of the Women’s Alliance. This institution, birthed from the crucible of cultural erosion and economic upheaval in 1991, is more than a mere NGO. It is a declaration of resistance, a bastion of Ladakhi heritage struggling against the encroaching tide of modernity.

The alliance’s center stands as a testament to traditional craftsmanship—its architecture echoing the ancient rhythms of Ladakhi design, while housing a labyrinth of offices, meeting rooms, and a craft shop brimming with the creations of village women: hand-woven shawls, intricate baskets, gleaming brass spoons, and vibrant vegetable seeds. An annual festival unfolds here, a vivid tapestry of local knowledge and skills. Women in vibrant traditional garb display ancestral talents—spinning, cooking, pressing oil from mustard and apricot kernels—each movement a dance with the past. They address an audience of local dignitaries with a quiet, steely pride, their voices weaving a narrative of cultural preservation. “Everything we need, we can make ourselves,” asserts Dolma Tsewang, the alliance’s director. “We are rich in resources; we must embrace what we have, as our ancestors did. Our pride lies in our dress, our food, our land.”

Tsewang, having traversed Europe thrice, remains unimpressed by the allure of Western consumerism. “Your elders see their grandchildren only once a year, and it seems you have no time to savor life. In many ways, we are richer here,” she reflects, her eyes hardened by the stark contrasts between her homeland and the West.

Amid the clamor of opportunistic Kashmiris, the diesel-spewing taxis, and the disheartening sight of children unable to count to ten in their native tongue, there remains a flicker of hope for a sustainable Ladakh. In the smoky confines of the sleek Ibex Hotel bar, even the sharp-suited businessmen and dashing trekkers grapple with the costs of ‘development’. “This is the juncture where we peer back at what we have lost and gaze forward to what Ladakh might become in the next two decades,” muses a 27-year-old local. “We need to rediscover ourselves.”

The impact of a cash economy, rife with corruption and creating a chasm between Levi’s-clad youth and their parents, is undeniable. Yet, an extraordinary awareness prevails. People grow weary of the hollow promises of progress and remain open to alternative paths.

Thupstan Paldan, a prominent Ladakhi intellectual, perceives a glimmer of hope in this crossroad. “Once, we followed development blindly,” Paldan observes. “Now, we understand that progress isn’t unmitigated good. Sugary tea can’t nourish like our salty butter tea; rice lacks the strength of barley. Even in remote villages, there’s a growing skepticism towards chemical fertilizers.”

Helena Norberg-Hodge shares a more optimistic view, noting a revival of traditional values amidst modernity’s encroachments. “There is a newfound consciousness,” she notes. “Renewable energy has become mainstream; local food’s nutritional value is being recognized; and organic farming is gaining traction. It’s remarkable to witness these changes.”

Does she believe Ladakh can revert to its former ‘ecotopia’? “Ladakh can never return to what it was,” Norberg-Hodge muses. “But perhaps it is coming full circle. Three decades ago, I admired the sophistication of the Ladakhi culture—a model of sustainability, cooperation, and peace. While the West was just beginning to discuss environmental issues, Ladakh had an innate grasp of ecology. Now, we see a convergence of old and new values.”

Back in Likir, Tsering Lundup, the headmaster, arrives at a distant field, distributing scythes to Nepali laborers. To their surprise, he takes one for himself and begins cutting thick green iris stalks, a delicacy for sheep and goats.

“Why would I ever want to leave this?” Lundup calls out, gesturing to the horizon where the sun sinks behind purple mountains, casting a golden glow over a distant monastery and barley buds swaying gently in the breeze.

Despite the seductive veneer of Western development and globalization’s pressures, the pre-industrial past in Ladakh is more than a distant memory. The current generation, deeply rooted in the land, is unlikely to let go easily.

Ladakh: A Land at the Crossroads

Perched in the high-altitude deserts where India converges with China and Pakistan, Ladakh is a region of profound strategic significance within the troubled Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. Its first real brush with the outside world came in the 1960s, with the Indian army’s intrusion bringing labor shortages, cash influxes, and a replacement of traditional fuels with diesel and kerosene.

The floodgates truly opened in 1974 when the Indian government decided to expose the region to tourism and development. By 1986, imports had surged to 6,000 tons of wheat and rice, 900,000 pounds of coke, and 50,000 cubic feet of firewood. That year, nearly 20,000 tourists visited Ladakh, a number equivalent to almost a quarter of the local population. Promises of a better life in the cities and the influx of heavily subsidized goods began to displace traditional livelihoods, pushing people toward clerical jobs, trekking guides, and taxi driving. The transition was swift, paralleling the American land exodus and the British Industrial Revolution—but on an accelerated timeline.

For Thupstan Paldan, a monk and leading intellectual, the decline of Ladakh’s agriculture is nothing short of a catastrophe. “Our ancestors nurtured these fields,” he laments. “They are the bedrock of our culture. Once, self-sufficiency was a source of pride. Now, we are dependent on the army, subsidies, and tourism. It’s madness for a place that is cut off for eight months each year.”

Reality Tours: The New Lens

The media and advertising often present an alluring, distorted image of urban consumer culture to non-Western societies, driving young people to reject their heritage. The International Society for Ecology and Culture’s ‘reality tours’ offer Ladakhi leaders a chance to witness the realities of Western life firsthand. These tours include visits to nursing homes, landfills, drug rehabilitation centers, and also showcase inspiring examples of organic farming and sustainable communities. Upon returning to Ladakh, participants share their experiences through local media and village meetings, providing a more nuanced view of industrialized life and fostering cultural pride.

Ladakhi ‘reality tourists’ often remark:

– “If he has siblings, why doesn’t he live with them?” (To the director of a London homeless shelter.)

– “They were always spending money and didn’t even bake their own bread.”

– “They call it organic. It’s just like what we do.”

– “They have special doctors and pills just for people who are unhappy.”

– “They were always rushing or on the phone or driving kids somewhere. They never seemed to have time to enjoy themselves.”