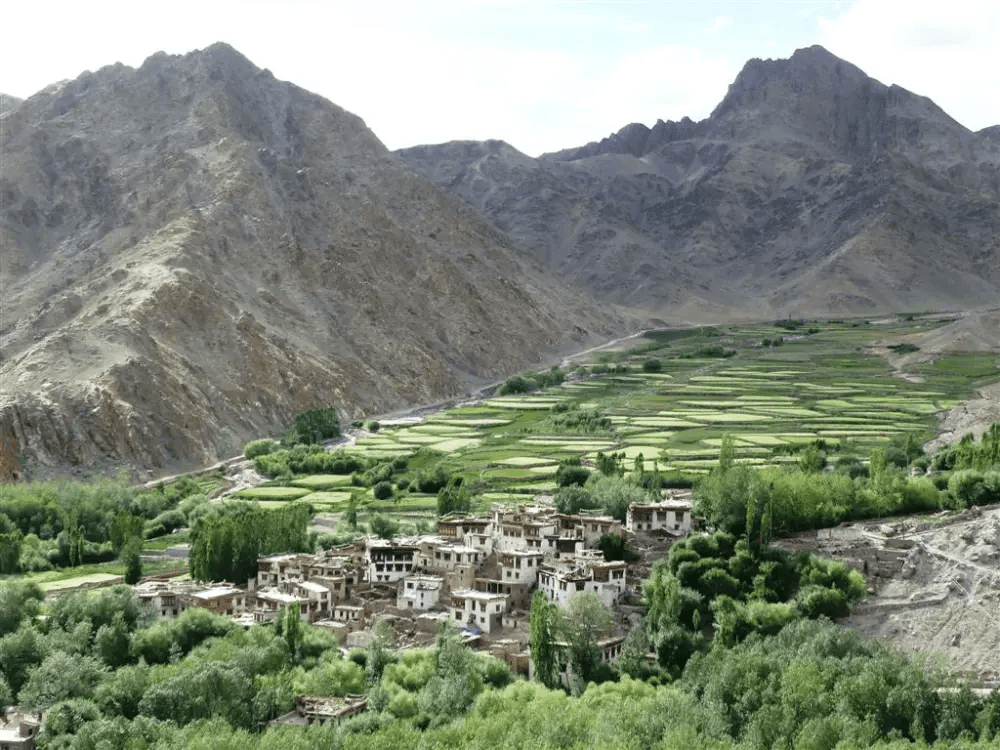

Introduction to Khardung Village – A Hidden Gem of Nubra Valley

Tucked deep within the folds of the Nubra Valley and hidden beyond the iconic Khardung La Pass lies a village that has remained untouched by the frantic beat of modern tourism. Khardung Village, Ladakh, is not just a geographical destination—it’s a living, breathing chapter of Himalayan heritage that few travelers have the privilege to experience. With its sparse yet resilient population, traditional yak-farming lifestyle, and ancient rhythms of mountain survival, the village offers more than a visit—it offers a lesson in simplicity, sustainability, and cultural endurance.

This high-altitude hamlet sits at approximately 3,975 meters (13,041 feet) above sea level, resting quietly on the northern shoulder of Khardung La. Often mistaken for just a pass en route to the Nubra Valley, the village of Khardung itself rarely makes it onto standard travel itineraries. But for those with the curiosity to venture off the beaten path, it opens a portal to a world where life is dictated by the movement of yaks, the wisdom of elders, and the silent prayers whispered through colorful Buddhist flags flapping in the wind.

Khardung Village is not for the hurried traveler. There are no luxury resorts here. No bustling bazaars. No Instagram-friendly cafés. Instead, visitors are welcomed with butter tea served in metal cups, stories passed down from great-grandparents, and air so pure it seems to cleanse the soul. The roads may be rough, but the reward is profound: an immersion into a way of life that modernity has not yet diluted.

With a population that relies on high-altitude farming, limited electricity, and centuries-old traditions, the community of Khardung remains remarkably self-sufficient. What keeps them going? The answer lies in the yak—the sturdy, shaggy animal that provides milk, meat, fuel, wool, and companionship. Yak farming here is not just livelihood; it is identity, economy, and cultural glue.

This guide aims to go beyond the surface and into the heart of Khardung. We will trace winding paths from Leh to the edge of civilization, explore the day-to-day lives of yak herders, and uncover the spiritual and environmental wisdom embedded in every stone and pasture. Whether you’re a responsible traveler seeking offbeat adventures or a storyteller in search of Himalayan truths, Khardung Village promises to challenge your expectations—and perhaps, change your perspective on what it means to live well.

Life Beyond Khardung La – Entering a Remote Ladakhi World

Crossing over Khardung La is more than just a bucket-list drive across one of the highest motorable roads on Earth—it’s a passage into a different rhythm of life. While most travelers descend into the sand dunes of Hunder or seek photos in Diskit, very few make the turn toward Khardung Village, a quiet hamlet suspended in time. This stretch of road leads not to popular sightseeing spots, but to the edge of isolation, where human resilience and nature’s severity coexist in delicate balance.

Unlike the bustling town of Leh, the pace here is unhurried. Every sunrise in Khardung is met with the sound of yak hooves against frozen earth, the scent of woodsmoke from dung-fueled hearths, and the slow, deliberate rituals of rural Himalayan life. This is not a place of convenience—but it is a place of profound depth. The remoteness is not an obstacle, but rather its greatest strength. Khardung Village remains unspoiled by tourism, untouched by commercialization, and unbothered by the expectations of the outside world.

The physical environment demands reverence. Towering cliffs, crumbling rock faces, and icy winds shape the very architecture of the village—houses built from mud, stone, and prayer. Every home seems to lean inward, toward the warmth of kinship, against the weight of the cold. Connectivity is sparse. There is no mobile signal in most corners. Internet access? Forget it. And yet, every visitor soon realizes: nothing is missing here. The connection you find is not digital but human.

Seasonal rhythms define everything. The summer months are brief but vital—fields are cultivated, dung is dried, and trade routes become briefly accessible. In winter, the village folds into itself. Snowfall isolates Khardung entirely, cutting it off for weeks or months. This forces residents into a relationship with the land that is not exploitative, but symbiotic. There’s no room for waste, excess, or indulgence. Every act—from boiling water to spinning yak wool—is done with care, intention, and ancestral wisdom.

Travelers who make it this far often describe the experience as a form of recalibration. Here, survival is not dramatic; it’s daily. There’s an unspoken dignity in the routines—hauling ice, fetching wood, milking yaks—that reveals what modernity often obscures: the quiet nobility of necessity. In Khardung, you do not witness a “simple life” in the romantic sense—you witness a strong life, one honed over centuries against the wind and stone of the Himalayas.

Yak Farming in Khardung – The Lifeblood of a High-Altitude Community

In Khardung Village, yak farming is not a profession—it is a way of life passed down through generations, woven into the fabric of every family, field, and fire. At this altitude, where conventional agriculture is nearly impossible and winters can trap villages in snow for months, the presence of the mighty yak is not only a blessing—it is a necessity for survival.

The yak is an extraordinary creature. Built for the extremes, it thrives where few other animals can: on steep, frozen hillsides and thin air that would leave most breathless. In Khardung, herders rely on yaks for everything. Yak milk is turned into cheese, yogurt, and butter—used not only for sustenance but also for trade with neighboring communities. Yak dung, dried and stored during the warmer months, becomes the primary fuel source during the bitter winter, when wood and gas are out of reach. Yak wool, coarse but warm, is spun into blankets, jackets, and woven goods that shield families from sub-zero nights.

Every morning in Khardung begins with the yak. Herders rise before the sun to lead their animals to high pastures, where hardy grasses grow between scattered rocks. It is a daily migration—up and down the slopes, through fog, wind, and snowfall. The herders speak to their yaks in soft Ladakhi murmurs, with a familiarity that suggests companionship more than ownership. These animals are more than livestock; they are co-survivors.

Visitors to Khardung may be surprised by how integral the yak is to the local economy. In nearby Leh or Nubra Valley markets, one can find yak butter tea, chhurpi (dried cheese), and yak wool scarves—all sourced from villages like Khardung. Yet the economic value pales in comparison to the cultural weight. Herders recite folk songs about their animals, share stories of blizzards weathered together, and bless newborn calves in quiet, Buddhist-inspired rituals.

Unlike modern dairy farms or commercial livestock operations, yak herding in Khardung remains sustainable. The animals are allowed to roam, graze naturally, and live according to the mountain’s rhythm. There is no overproduction. There are no artificial enclosures. Just humans and animals, working together in harmony with the land. In an era where sustainability has become a buzzword, Khardung lives it without the branding.

To understand Khardung is to understand the yak—not just as an animal, but as a symbol of endurance, generosity, and coexistence with nature. For the traveler who takes time to observe, to listen, and to connect, the yak becomes more than a curiosity. It becomes a teacher.

People, Culture & Sustainable Life in Khardung

At first glance, Khardung Village may appear quiet, even austere. But spend a single day among its people and you’ll discover a world brimming with dignity, humor, and enduring cultural memory. The villagers live by an unspoken code of resilience and mutual respect. In an environment that gives little freely, the people of Khardung have learned to give to each other, building a community where cooperation is not a virtue—it is a survival strategy.

Families in Khardung often live in multi-generational households, where grandparents, parents, and children share duties, resources, and meals. Children learn early how to tend yaks, collect dung, and assist in seasonal farming. There is no school bus, no internet-connected classroom—but there is learning. Storytelling is a central form of education. Elders pass down knowledge of weather patterns, medicinal herbs, and moral tales rooted in Buddhist philosophy.

The spiritual life of the village moves in quiet tandem with the seasons. Small stupas and prayer flags dot the village paths, and even the humblest homes keep an altar in the corner, adorned with yak butter lamps and images of the Dalai Lama. Buddhist rituals in remote Ladakh are less about grand festivals and more about daily rhythm: the chanting of mantras at dawn, the turning of prayer wheels during walks, and acts of compassion woven into everyday behavior.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Khardung is its sustainable lifestyle, not as a conscious movement, but as an inherited necessity. The land is used mindfully. Nothing is wasted. Rainwater is collected. Animal dung is dried for fuel. Fields are rotated, and wild plants are foraged with care. Solar panels now dot a few rooftops, not because sustainability is trending—but because innovation here means finding quiet solutions to harsh problems.

Local cuisine reflects this same ethic. Meals are simple but hearty—barley flour (tsampa), yak milk curd, butter tea, and seasonal vegetables like wild spinach. The food is not only nourishing but deeply local, carrying the flavors of altitude, effort, and ancestral care. For travelers lucky enough to be invited into a Ladakhi kitchen, the experience is more than culinary—it is cultural.

Visitors should understand that Khardung is not a place to consume, but to learn from. Here, people live without many of the conveniences that modern cities take for granted. And yet, they are rich—in wisdom, in time, in connection to their surroundings. As the outside world rushes toward artificial intelligence and hyper-connectivity, Khardung quietly demonstrates a different kind of intelligence: one rooted in balance, respect, and the unbreakable thread between people and place.

Responsible & Eco-Friendly Travel to Khardung

Traveling to Khardung Village is not simply about arriving at a destination—it’s about stepping respectfully into a living community. At over 3,900 meters above sea level, every resource here is precious. Water is drawn by hand, food is grown seasonally, and even waste is managed with care. This is why eco-conscious travel in Ladakh isn’t a marketing label—it’s a necessity, and a responsibility for every visitor who makes the journey.

One of the best ways to honor this environment is to travel light and consume less. Bring reusable water bottles, avoid packaged snacks, and minimize plastic waste wherever possible. In a place where waste disposal is minimal and recycling is virtually nonexistent, the trash you carry in must be carried out. Leave no trace is not just a slogan in Khardung—it’s the only way the village continues to thrive without harm.

Choosing to stay in a local homestay rather than a hotel helps ensure your visit benefits the village directly. Homestays offer far more than just a place to sleep—they offer stories, shared meals, cultural exchanges, and the chance to experience true Ladakhi hospitality. Your payment goes straight to the family hosting you, contributing to education, farming supplies, and healthcare needs in ways that are immediate and impactful.

Respect for local culture is another key pillar of sustainable tourism in Khardung. This means dressing modestly, asking permission before photographing people or sacred sites, and learning a few Ladakhi or Hindi phrases as a gesture of goodwill. It also means listening more than speaking. Many travelers come with stories to tell. The wiser ones leave with stories they were lucky enough to hear.

If you’re trekking to or from the village, consider hiring local guides or pack animals—especially yaks—rather than bringing outside logistics. Supporting the local economy through employment, even briefly, helps build long-term sustainability and empowers residents to preserve their heritage. Avoid motorbikes or noisy vehicles in the village itself, as the tranquility here is not something to be disturbed, but protected.

Finally, perhaps the most eco-friendly act is to slow down. Stay more than a day. Take time to walk, to sit, to observe the mountain shadows shifting over rooftops. A rushed visit consumes resources; a patient visit enriches both traveler and host. In Khardung, the most meaningful journeys are not measured in distance—but in depth.

Khardung Through the Eyes of Locals – Stories from the Edge

To truly understand Khardung Village, one must see it not as a remote destination but as a place shaped by generations of memory, myth, and lived resilience. This isn’t the kind of knowledge found in maps or guidebooks—it lives in the stories passed down over cups of salted butter tea, in the pauses between breaths, in the worn hands of a yak herder who remembers every snowfall of the last fifty years.

There is Dorjay, a quiet man in his seventies who spent his entire life tending to his herd. He speaks little, but when he does, his words are poetry: “The mountain knows when you are patient. The yak knows when you are kind.” He remembers winters when the village was snowed in for two months straight, and the only food they had was dried tsampa and a shared sack of potatoes. Yet he smiles—not in bitterness, but in pride. Life here was never easy, but it was always earned.

Tsering Dolma, a mother of four, recalls the day electricity first reached the village. “I remember the bulb lighting up. My children clapped, and my husband cried.” For years they relied on oil lamps and the glow of yak-dung fires. Now, with a single solar panel and careful use, they can charge a phone, study after sunset, and call a distant relative once a week. Her story reminds us how modernity enters slowly in these mountains, and when it does, it is met with reverence.

Even the children carry stories. A ten-year-old boy named Namgyal tells tales of the “ghost wind” that comes through the pass at night, rattling doors and howling like a lost spirit. These stories blend Buddhist symbolism with ancient oral tradition, revealing how deeply spirituality and nature are intertwined in the worldview of Khardung’s youngest generation.

But not all stories are romantic. There are murmurs of change—of youth leaving for Leh or Delhi, of fields left unplanted because no one remains to tend them. Elders speak of traditions fading. The modern world is encroaching, slowly but inevitably. Yet, what remains is powerful: a community that still sings its own songs, walks its own paths, and honors the wisdom of the land.

Visitors who pause long enough to listen may leave with more than just photographs. They carry voices, impressions, and lessons that can’t be captured by GPS. In Khardung, stories are not entertainment—they are survival, identity, and inheritance. And they are generously shared with anyone willing to hear them with an open heart.

Planning Your Visit – Travel Tips for Khardung Village

If Khardung Village has sparked your curiosity, it’s time to plan your visit with care. Unlike popular destinations in Ladakh, this remote village demands not only logistical preparation but a certain mental attitude—one rooted in respect, patience, and adaptability. Visiting Khardung is not about sightseeing. It’s about immersion. And for that, thoughtful planning is essential.

When to Visit: The ideal time to visit Khardung is between late May and early October. During these months, the road over Khardung La is typically accessible, weather conditions are stable, and the village is alive with agricultural and pastoral activity. June and July bring the full bloom of life, while September offers golden barley fields and crisp post-monsoon air. Winters are brutally cold, and snowfall can cut the village off entirely. Visiting in winter is only advised for experienced travelers accompanied by locals.

Getting There: Start your journey from Leh. From there, Khardung La Pass—around 39 kilometers from Leh—is your gateway. After crossing the pass, a lesser-traveled road branches toward Khardung Village, which lies roughly 31 kilometers north of the pass. Hiring a local taxi with a driver who knows the region is highly recommended. Public transport is limited or non-existent. Ensure your vehicle is well-maintained and carries a spare tire, extra fuel, and water.

Accommodation: There are no hotels in Khardung Village—only the warm embrace of homestays. Several families open their doors to visitors, offering clean bedding, home-cooked meals, and the rare chance to live life as the villagers do. Booking in advance may not be possible due to limited connectivity, so it’s best to coordinate through a local travel agent or make arrangements while in Leh.

What to Pack: Essentials include warm layered clothing (even in summer), sun protection (hat, sunglasses, sunscreen), reusable water bottles, altitude sickness medication, and cash—there are no ATMs in or near the village. A headlamp, wet wipes, and water purification tablets are also smart additions. If you’re staying with locals, consider bringing small gifts like dried fruits, notebooks, or solar lights as tokens of gratitude.

Altitude Awareness: Khardung sits above 3,900 meters. Spend at least two days in Leh to acclimatize before heading higher. Drink water frequently, avoid alcohol, and take it slow. Listen to your body. If symptoms of acute mountain sickness occur—headache, nausea, fatigue—descend immediately.

Responsible Behavior: Dress modestly, minimize waste, and follow local customs. Always ask before taking photos. If you’re trekking nearby, consider hiring local guides and porters to directly support the village economy. Be humble, be curious, and remember: you are a guest in a place where traditions have survived for centuries without the need for outside validation.

Conclusion – Khardung Village: The Soul of Ladakh

In a region of towering monasteries, dramatic landscapes, and sacred lakes, Khardung Village offers something quieter—but no less profound. It is a place where modernity hasn’t yet erased the cadence of ancestral life, where yaks still plod through frozen fields, and where each sunrise carries the weight of endurance and grace. In a world increasingly obsessed with speed and spectacle, Khardung whispers a counter-narrative: slow down, listen closely, and stay present.

This remote hamlet beyond Khardung La is more than a destination. It is a classroom of sustainability, a museum of mountain wisdom, and a sanctuary for the spirit. Khardung Village represents the soul of Ladakh—not polished or curated for tourism, but raw, resilient, and beautifully real. Its people do not ask to be photographed; they ask to be remembered. And when you leave, you will carry with you more than souvenirs. You will carry a deeper awareness of what it means to live in harmony with land, animals, and community.

Whether you’re a slow traveler, a cultural explorer, or simply someone yearning for a destination that still feels untouched, Khardung offers what few places can: authenticity without performance, tradition without nostalgia. The path here may not be easy. It may not even appear on most maps. But for those willing to look beyond the obvious, Khardung Village will remain not just a memory—but a quiet revolution in how we understand travel, simplicity, and human connection.

So go—not as a tourist, but as a learner. Walk the narrow trails, share a fire with a herder, sip yak butter tea slowly, and leave your expectations behind. Khardung does not exist to impress. It exists to endure. And if you are lucky, it will imprint itself on you in a way that never leaves.