Where the Road Learns to Breathe Between Two Skies

By Declan P. O’Connor

I. Opening: Entering a Corridor Shaped by Wind, Memory, and Borderlines

The First Turn Beyond Kargil Town

For many European travelers, Kargil has long been a name borrowed from headlines and half-remembered news footage. Out here, beyond the last cluster of tyre shops, that reputation softens, reshaped by the sight of laundry lines on flat rooftops, the call of children following a cricket ball down a lane, the patient tilt of donkeys learning the shape of the road. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is not a destination in the conventional sense; it is a lived-in passage, a chain of communities that happen to sit near borders and battlefields but continue to prioritize crops, schooling and marriages. What awaits you is not a museum of conflict but a series of villages that have learned to keep going anyway, stitching ordinary days into an extraordinary landscape. Crossing that first invisible line beyond town, you are not just changing altitude; you are entering a place where the road itself is an introduction.

The Frontier as a Living Landscape

The phrase “frontier corridor” can sound abstract, like a line on a map argued over in distant capitals. In reality, the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is thick with life: smoke rising from kitchen chimneys, prayer flags stiff with frost, flocks of sheep pushing pebbles down the slope as they move, and soldiers posted on ridgelines that most of us will never climb. It is a landscape where memory is not confined to memorials, but embedded in the terraces, in the weather-beaten faces of people who have watched the road change from mule track to highway. The frontier here is not only geopolitical; it is climatic, cultural and emotional, the place where green fields concede to cold desert, and where the idea of home must contend with snowdrifts and history.

In the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, the map in your hand is always incomplete; the real contours lie in the stories people are willing to tell you over tea.

As you move from Kargil towards Dras and eventually to the high gate of Zoji La, the corridor continually rearranges itself. One hour the mountains are close and severe, the next they open just enough to reveal a village wrapped in orchards and stone. It is easy to think of such a place only in terms of risk and hardship, but that would miss the quieter truth. Life here is not an act of stoic suffering; it is a practiced negotiation between what the mountains allow and what human beings insist on building anyway. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is therefore not just scenery on the Srinagar–Leh road. It is a living experiment in how communities can remain rooted in a place that outsiders still misread as merely strategic.

II. Kargil: A Town Where Continents and Centuries Meet

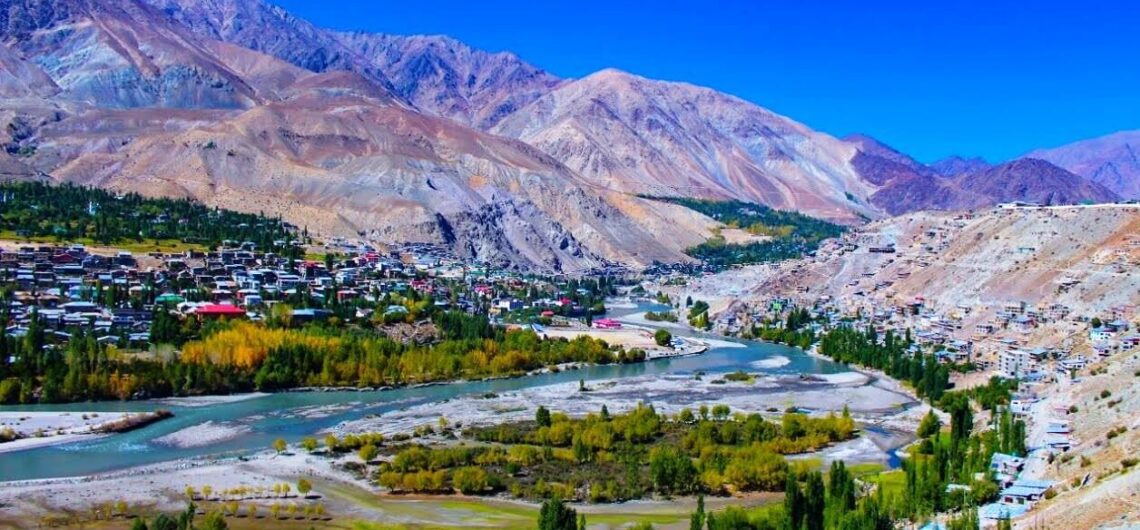

A River Town with Unexpected Warmth

Kargil, at first glance, looks like a junction, a necessary overnight stop on the long run between Srinagar and Leh. Look a little longer, though, and you begin to notice how the town draws its personality from the Suru River cutting through it, from the bridges that knit one bank to the other, from the way the bazaar tilts towards the water as if for reassurance. In the early evening, when shop shutters rattle and the last school buses grind uphill, the town feels less like a waystation and more like a riverine organism, breathing in time with the current below. This is where many journeys into the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor begin, with a pot of tea on a guesthouse balcony and the low hum of traffic trying to decide whether it belongs to Kashmir or Ladakh.

For a European traveler used to neat historical districts and signposted heritage trails, Kargil can be disorienting in the best possible way. Layers of history are present but not curated: caravan pasts hinted at in old warehouses, Central Asian trade routes remembered in family stories rather than plaques, religious traditions woven into the pattern of daily errands rather than set aside in a museum. You might wander past a bakery where flatbread is slapped against the walls of a clay oven, then turn a corner to see schoolchildren in modern uniforms scrolling on their phones. The town’s role as the informal capital of this stretch of the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor means that it holds together diverse influences: Shia processions, Sunni mosques, Buddhist families from surrounding villages, and traders who have learned to translate prices in several languages. What emerges is not a picture-perfect destination, but a working town that quietly insists you take it on its own terms.

The Stories Stored in Kargil’s Ridges

Kargil’s ridgelines are not just natural defences; they are memory banks. On one side lie the road and river, on the other the smaller paths that climb towards hamlets, shrines and seasonal pastures. From almost any rooftop, you can look up and see what appears to be emptiness, only to discover that those apparently bare slopes host bunkers, watch posts and the ghost traces of older routes. Before national borders hardened and the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor became a phrase in security briefings, these valleys connected through trade and marriage. The road to Skardu, now cut by politics, once carried salt, wool and stories between communities that still share surnames.

Spending a day in Kargil before following the corridor towards Hundurman or Dras offers more than just acclimatization. It grants you time to listen. Hoteliers will tell you about winters when snow closed the highway for weeks, forcing residents to improvise everything from fresh vegetables to medicine. Taxi drivers can point out slopes where their fathers walked with pack animals instead of engines. Young people, scrolling through global news on patchy networks, are just as capable of holding a conversation about football as they are about the latest landslide on the highway. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor begins here, in a town that has learned to be both guardian and host, where hard edges in the collective memory are softened by the daily routine of getting children to school and ensuring the bread comes out of the oven on time.

III. Hundurman and Hardass: Life at the Edge of Maps

Hundurman Broq and the Line Where Maps Go Quiet

If you follow a spur road from Kargil towards the Line of Control, the modern map begins to shade itself in grey. Somewhere above the river’s bend, stone houses cling to a slope that seems too steep to support them. This is Hundurman Broq, a village whose story is told as much through what has been left behind as through what remains inhabited. Walking through its narrow lanes, you move between homes now serving as a kind of open-air archive: rooms frozen in the middle of ordinary tasks, cupboards with crockery, schoolbooks, and clothing that suggest families departed in haste. It is here, on the edge of the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, that you begin to understand how borders can be redrawn without a single stone in a village wall moving.

For visitors, Hundurman offers neither spectacle nor comfort in the usual sense. What it offers instead is perspective. It asks you to imagine what it means to wake up one morning and discover that the line on the map has shifted, altering your citizenship without your consent. The current residents, settled just beyond the old cluster of houses, are careful about how they narrate this history, balancing pain with a matter-of-fact resilience. You might be shown a room that still holds a family’s belongings from before the partitioning of the valley, then invited for tea in a new home looking over the same river. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor can seem abstract until you stand here and realize that “frontier” is not a general noun but a specific experience, lived by people who have had to accommodate both soldiers and tourists in their vocabulary of survival.

Hardass: A Village Strung Along the River and the Road

Return to the main highway and continue east, and the village of Hardass appears almost as an afterthought along the river’s curve, houses and fields strung between rock and tarmac. It is easy to drive past, assuming it is just another roadside settlement, but that would miss the subtle choreography at work. Terraced fields adjust themselves to both gravity and road access, children learn to judge the timing of passing trucks before sprinting across, and families design their days around both the sun and the bus schedule. Here the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor looks less like a grand strategic zone and more like a long, linear village, stitched together by irrigation channels and power lines.

Spend a little time walking in Hardass and its quiet complexity emerges. Behind the row of buildings nearest the highway, narrow alleys lead to courtyards where women sort apricots or hang laundry, where livestock are coaxed into shaded pens, and where elderly men sit against a wall, following the news on a radio. The river below carries meltwater from glaciers you cannot see, while above, unmarked paths lead to grazing lands where shepherds still read the weather more accurately than any smartphone app. Hardass is one of those places where the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor feels intimately domestic: a place where international lines and military convoys are part of the backdrop, but where the pressing concerns are more immediate—whether the harvest will be good, whether the school will get a new teacher, whether the next winter will be kind or cruel.

IV. Chanigound and Kaksar: Villages Listening to the Hills

Chanigound: Everyday Life Under Watchful Ridges

Further along the highway, the village of Chanigound sits in a bowl of land that feels both sheltered and scrutinized. The ridges around it rise quickly, folding into each other like the shoulders of giants interrupted mid-conversation. Somewhere up there, out of sight, are vantage points and posts; down here, in the lanes and fields, life goes on with a deliberate, almost stubborn normality. Children walk to school past irrigation channels, boys kick footballs on patches of ground that double as threshing areas, and women carry bundles of fodder along paths so narrow that the modern world seems to have shrunk to the width of one person’s shoulders. It is in such places that the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor reveals its most human dimension.

For a visitor, Chanigound is not a checklist stop. There are no big-ticket monuments or curated attractions. What it offers instead is the chance to observe how a village absorbs the presence of the highway without letting it define everything. Homestays are modest but hospitable, cooking is seasonal and unpretentious, and conversations drift easily between crops, relatives working in distant cities, and the occasional commentary on politicians who feel very far away. In the evenings, when the last vehicles have passed and the valley grows quiet again, the village settles into a rhythm of low voices, the clink of utensils, and the distant bark of dogs. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, seen from Chanigound, is less a dramatic headline and more a long-term negotiation between the demands of security and the desire for an ordinary, dignified life.

Kaksar: From Headlines to Harvest Seasons

Kaksar is a name that once appeared on maps mainly in the context of conflict. Today, as you roll into the village, what strikes you first is not the memory of artillery but the sight of carefully tended fields, willow trees tracing the waterways, and houses that seem to lean towards the sun. This is perhaps the most challenging aspect of traveling through the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor: learning to hold the reality of past violence alongside the equally real present of people who want to be known for more than the worst days of their history. In Kaksar, you may see memorials and hear references to tense periods, but you will also see children racing home from school, and elders examining the sky to judge the chances of late rain.

Walk a little off the highway, and Kaksar’s everyday life becomes visible. Women work in fields bounded by stone and water, conversations flowing as steadily as the irrigation channels. Men repair tools, reinforce walls before winter, or gather in small groups to discuss news they have pieced together from radio, television, and social media. Young people are as likely to be discussing higher education and job prospects as they are to be reciting stories from the late 1990s. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, in villages like Kaksar, is not a frozen warzone but a living landscape where people are constantly editing their own narrative: acknowledging what happened, but choosing to focus on harvests, schooling and the incremental improvements that mark progress here—a new road surface, a more reliable power line, or a healthcare worker able to stay the winter.

V. Dras: Gateway of Wind, Cold, and Enduring Stories

Arriving in One of the Coldest Inhabited Places on Earth

As the road climbs towards Dras, the air acquires a sharpness that cuts through even the best-layered clothing. By the time you reach the town, you are in a place that proudly, and a little wearily, carries the label of being among the coldest inhabited settlements on the planet. In winter, temperatures here plunge to numbers that look like accounting errors; in summer, the memory of that cold never quite leaves the conversation. Houses are built to huddle against one another, roofs and walls carrying the scars of many seasons of snow. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor narrows here, squeezed between mountains that seem intent on testing just how committed humans are to living in such conditions.

For a European reader accustomed to tidy alpine resorts, Dras offers a more uncompromising version of mountain living. There are no chocolate-box façades or carefully staged viewpoints; instead, there is a town that has rebuilt itself after trauma, rebuilt roads, and rebuilt the confidence to welcome travelers again. Roadside stalls sell tea that is more necessity than leisure, and the warmth of a simple bowl of soup is magnified by the wind rattling at the door. Walk a little away from the highway and you will find small lanes where children play under laundry lines heavy with winter clothing even in autumn, and where families discuss whether the coming snow will arrive early or late this year. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor at Dras is defined not just by latitude and altitude, but by an attitude that treats extreme cold as a daily inconvenience rather than a spectacle.

The Dras Valley as a Cultural Crossroads

Beneath its meteorological reputation, Dras is a cultural meeting point. Languages blend here: you may hear Shina alongside Urdu, Ladakhi words slipping into everyday conversation, and English phrases picked up from travelers and television. The valley holds onto Dardic roots even as it participates fully in contemporary India, creating a texture that does not fit neatly into tourist brochures. Mosques and shrines nestle against the slopes, prayer calls and temple bells sharing the same air that thunderstorms and snow squalls claim at other times. In this stretch of the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, identity is not a rigid label but a layering of traditions, loyalties and surviving habits.

Inevitably, conversations in Dras carry the echo of events that once made global headlines. Yet the people who live here have done something quietly radical: they have refused to let those headlines be the sole definition of their town. They speak of relatives working elsewhere, of students who have gone on to universities in plains cities, of experiments with greenhouses to stretch the growing season by a few crucial weeks. They discuss infrastructure in the same breath as festivals, politics alongside the condition of the road to Zoji La. Walking through Dras, you realize that the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is not a preserved battlefield, but a place where communities insist on having a future that extends beyond the vocabulary of conflict, even while acknowledging the memorials on the hillside.

VI. Zoji La: Where Ladakh Loosens Its Grip

Driving the Pass Between Stark Rock and Green Valleys

Beyond Dras, the highway begins to uncoil in earnest, looping into switchbacks that make even seasoned drivers grip the steering wheel a little tighter. The approach to Zoji La is a sequence of reveals: a bend that exposes a sheer drop, a slope of loose rock that has clearly surrendered to gravity more than once, a sudden glimpse of snow even in the shoulder seasons. This is the western gate of the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, the point where Ladakh’s spare, sculpted landscape starts to negotiate with the greener, more forested world of the Kashmir Valley. The drive over Zoji La is less about altitude numbers and more about the feeling that the mountains are asking, once again, whether you truly wish to pass.

In good weather, the pass can feel almost theatrical. Trucks and cars inch past one another on narrow stretches, horns and hand signals substituting for formal traffic management, prayer flags snapping in the wind at improvised roadside temples. In bad weather, the same road can close without apology, snow and landslides reminding everyone who really controls the timetable here. For travelers coming from Kargil and Dras, reaching Zoji La is both an accomplishment and a moment of transition. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor, with its villages strung along cold rivers and stark ridges, begins to recede in the rearview mirror, replaced by slopes that soften into meadows as you descend towards Sonamarg. You may feel a physical lightness as oxygen levels increase, but there is also a subtle sense of stepping out of a more intense register of geography into something more familiar.

A Frontier of Weather, Culture, and Imagination

Zoji La is often described purely in strategic or logistical terms: a vital link between regions, a pass that must be kept open for supplies. Stand there for a few minutes, though, and another dimension reveals itself. To the east lies the high, dry world that shapes the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor; to the west, the layered greens and waters of Kashmir. The pass is a hinge between climates, yes, but also between different ideas of home. For people living in Kargil, Dras, and the villages between, Zoji La has long been both opportunity and risk—an exit to markets and education, and a point of vulnerability to blockade and storm.

For visitors, the pass can prompt a quieter internal frontier. Leaving the corridor behind, you may find yourself replaying images of Hundurman’s stone houses, Hardass’s riverside fields, Chanigound’s narrow lanes and Kaksar’s terraces. The road ahead is easier, but a part of you remains with the communities that continue to live in the corridor year-round. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor teaches you that frontiers are rarely single lines. They are thickened spaces where weather, culture, politics and memory overlap. Zoji La, in that sense, is not just a high point on a map; it is a vantage point, offering one last chance to look east and consider what it means for people to make a durable life in places that others only pass through.

VII. Living and Traveling Slowly in the Kargil–Dras Frontier Corridor

How to Move Through the Corridor with Respect

The temptation, on a long Himalayan journey, is always to treat the in-between as expendable: to rush from celebrated destinations and assume that places like Kargil, Hundurman, Hardass, Chanigound, Kaksar and Dras are merely commas in the sentence. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor resists that haste. To experience it properly, you need to slow down your itinerary and your expectations. That might mean giving Kargil an extra night, using it as more than a refuelling stop. It might mean arranging a local guide to walk you through Hundurman’s older settlement, not as voyeurs of tragedy but as guests in a living community. It might mean choosing a homestay in Hardass or Chanigound rather than pushing on mechanically to the next town.

Respectful travel here also involves practical choices. Ask before photographing people, especially in areas where military presence is visible. Keep conversations about politics sensitive and proportionate, recognizing that those you meet may have a more intimate relationship with the subject than you do. Spend money where it matters: a meal at a family-run eatery, a night in a small guesthouse, a bag of local apricots rather than imported snacks. The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is not fragile in a romantic sense—its people are resilient—but it is vulnerable to being flattened into a simplistic narrative. Traveling slowly, listening more than you speak, and allowing the road to feel long rather than efficient are small acts that help preserve the integrity of a region that has already endured more than its share of external definition.

FAQ: Practical Questions About the Kargil–Dras Frontier Corridor

Q: How many days should I plan for the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor?

A: If you treat the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor as more than a transit route, three to four days is a comfortable minimum. That allows a night in Kargil, time to visit Hundurman, at least one overnight in or near Dras, and the flexibility to pause in villages like Hardass or Chanigound. Extra days give you space to handle weather delays and to simply sit with the landscape instead of rushing through it.

Q: Is the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor safe for foreign travelers?

A: While this is a sensitive border region, the highway is well-travelled and foreign visitors are a familiar sight. Security checks and checkpoints are normal and should be approached with patience and cooperation. Conditions can change, so it is wise to check recent travel advisories and to listen to local advice in Kargil or Dras. Most travelers report feeling welcomed and looked after, especially when they move with humility and follow local guidance.

Q: When is the best time of year to visit?

A: The Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is most accessible from late spring to early autumn, when the highway over Zoji La is generally open and snow has retreated from lower slopes. Early summer brings strong contrasts between snow on higher ridges and green fields below, while late summer and early autumn can offer clearer skies and quieter roads. Winter visits are possible but demanding, better suited to those comfortable with extreme cold and travel disruption.

Q: Can I stay in local villages, or should I base myself only in Kargil and Dras?

A: While Kargil and Dras offer more formal accommodation, it is increasingly possible to arrange homestays in smaller villages along the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor. Staying in places like Hardass, Chanigound or nearby settlements gives you a deeper sense of daily life. Homestays are simple and family-run, so flexibility, respect for house rules, and a willingness to adapt to local routines are important.

Conclusion: What Remains After the Last Pass

When you finally leave the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor—whether dropping west through Zoji La or heading further east towards Leh—the road continues, but something in you moves more slowly. You carry with you the image of terraces under harsh light, of schoolchildren waving at passing vehicles, of stone houses in Hundurman holding the weight of interrupted histories. You remember Kargil at dusk, Dras under a hard blue sky, and the villages that seemed at first glance to be anonymous dots on the map but turned out to be complicated, dignified worlds unto themselves. Travel here is not about ticking off peaks or collecting superlatives; it is about learning how people construct a meaningful life in places that the outside world too often reduces to shorthand.

Perhaps the most enduring gift of the Kargil–Dras frontier corridor is a quieter understanding of frontiers themselves. They are not just lines defended by soldiers or negotiated by diplomats, but spaces held together by farmers, shopkeepers, teachers and schoolchildren who decide, day after day, to remain. Long after your vehicle has descended from Zoji La and the sharp wind has faded into memory, the corridor continues: rivers running, fields waiting for the next season, roads reopening after snow. If you are fortunate, a part of your imagination will remain there too, returning in odd moments to those villages between Kargil and Dras where the road learns, at last, to breathe between two skies.