Where Water Flows Like Time in Ladakh’s Cold Desert

By Elena MarloweIntroduction: Following the Flow of Meltwater

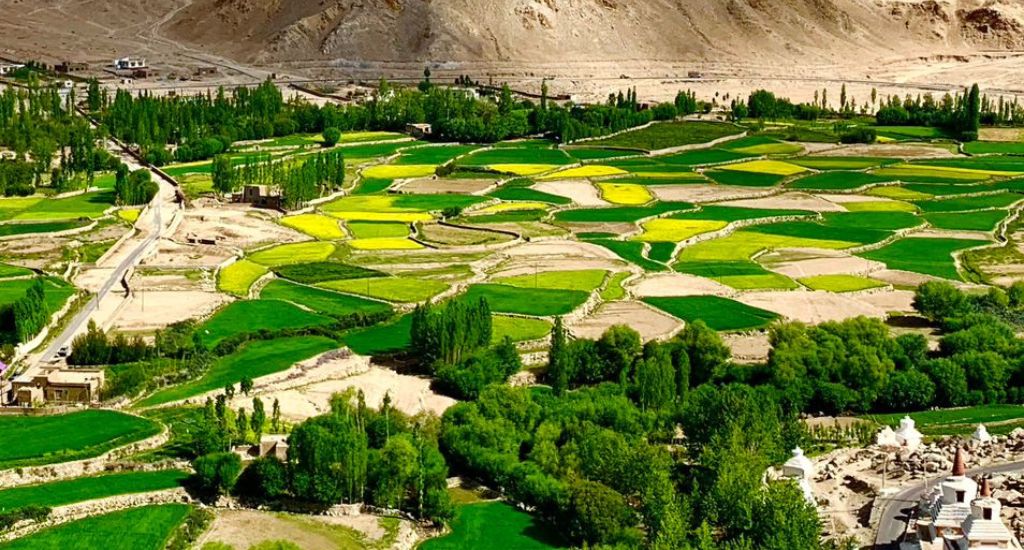

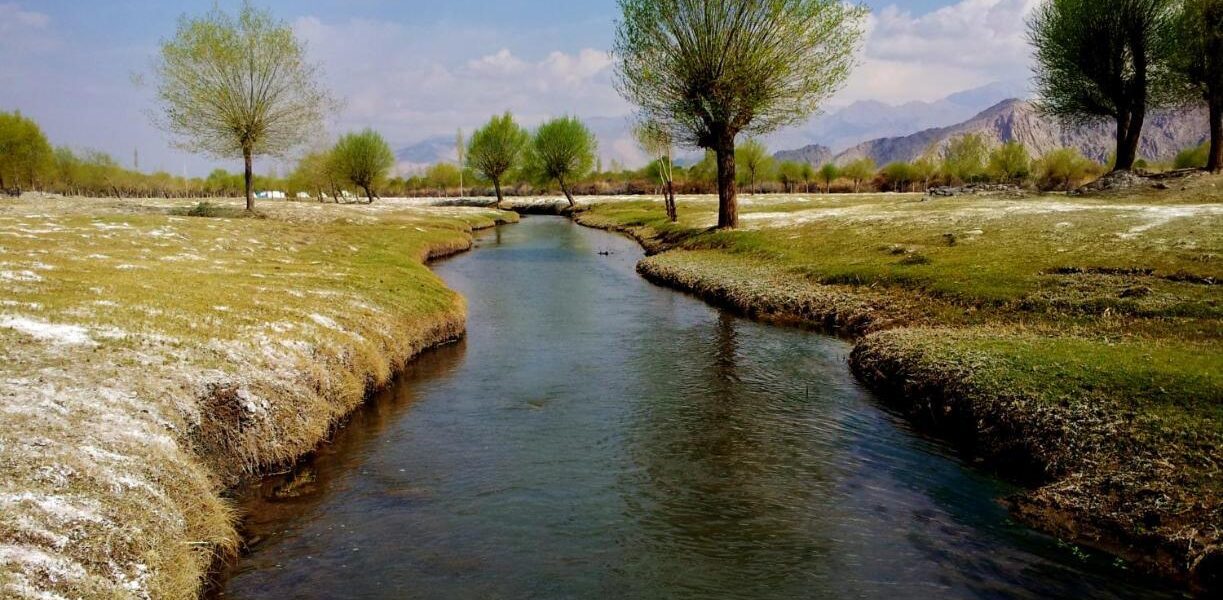

Arriving in Ladakh, one is immediately struck by the stark beauty of a high-altitude desert where rivers appear like silver threads in an otherwise ochre and stone-colored landscape. The valleys seem carved not only by geological time but also by centuries of human effort to coax life from arid soil. For the European traveler used to temperate climates where water flows abundantly and green fields stretch endlessly, Ladakh’s first impression is of dryness and fragility. Yet, hidden in this fragility is a sophisticated tradition of water management that has allowed generations of Ladakhis to thrive. The terrain is harsh—altitudes above 3,000 meters, scarce rainfall of less than 100 mm annually, and soil that at first glance seems inhospitable. And yet, barley fields sway in the wind, apricot trees bloom in spring, and villages shine with green patches surrounded by barren cliffs. This contrast compels one to ask: how has water been managed here for centuries? The answer lies in an ancient system of canals, known locally as khuls, that carry glacial meltwater across long distances. These canals are not just practical infrastructure; they are cultural arteries, shaping community life and symbolizing resilience. Walking through a Ladakhi village for the first time, one hears the faint gurgle of water weaving through stone-lined channels. These are not incidental trickles but carefully directed lifelines. Each sound of flowing water is a reminder that survival here is a collective achievement, dependent on cooperation, patience, and an intimate understanding of the natural world.

The Ancient Invention of the Khul System

Origins of Ladakh’s Irrigation Canals

Long before modern engineering reached these remote valleys, Ladakhis had already devised their own remarkable solutions to scarcity. The khul system, an intricate network of high-altitude canals, is believed to date back over a thousand years. Oral traditions trace its roots to early settlements that migrated into these valleys, bringing with them not only livestock and seeds but also the communal knowledge of harnessing water. The ingenuity lies in simplicity: by diverting meltwater from glaciers and streams, channels could carry life to otherwise barren slopes. In Europe, aqueducts such as those built by the Romans are celebrated as feats of civilization. In Ladakh, the khuls hold a similar significance, yet they remain largely unsung outside the region. These canals reflect a society that understood its fragile environment and responded with innovation rather than conquest. Archaeological traces, ancient stone linings, and historical records from monasteries point to a long tradition of constructing, repairing, and even ceremonially blessing these irrigation systems. For the traveler, standing beside a centuries-old canal that still carries water to green terraces is like touching history in motion. Each stone laid in its path tells a story of collective effort, reminding us that survival in Ladakh was never an individual endeavor but a shared mission.Early Settlements

The earliest villages in Ladakh were strategically placed where khuls could be dug. Without irrigation potential, no settlement could last long. This determined the shape of human geography in the region.Indigenous Ingenuity

Rather than relying on external technologies, Ladakhis developed systems suited to their environment, balancing gravity, slope, and water flow. This adaptation ensured sustainability for generations.Spiritual Dimension

Monasteries recorded and often sanctified the construction of khuls. Water was considered sacred, and building canals was not only technical but also spiritual work.Historic Continuity

Unlike temporary fixes, these systems have lasted centuries. Their endurance speaks of constant care, knowledge transfer, and the strength of community traditions.How Villagers Engineered Water from Glaciers

The real brilliance of the khul system lies in the technical mastery of channeling water without machines or pumps. Villagers mapped slopes with an eye for gradients, ensuring that water flowed steadily across distances sometimes exceeding several kilometers. Using nothing but simple tools, stone, mud, and wood, they created durable paths that balanced gravity’s pull with the need for control. At first glance, a khul might appear as a narrow trench, but its design reveals careful calibration. Too steep a gradient, and water rushes destructively; too gentle, and the flow stagnates. Ladakhi farmers mastered this balance through generations of observation and practice. Their methods anticipated modern hydrology in their intuitive understanding of velocity, pressure, and volume. Each spring, as glaciers begin to melt, teams of villagers work together to clear channels of ice and debris. These communal efforts reaffirm bonds while guaranteeing survival. To witness this annual ritual is to understand that engineering here is not simply science—it is also culture, obligation, and a rehearsal of solidarity.Measuring Slopes

Without modern instruments, villagers used sight lines, experience, and a shared memory of the land to decide gradients. Precision was born out of familiarity rather than calculation.Stone and Mud Craft

The canals are lined with stone to prevent erosion, sealed with mud, and reinforced with wooden stakes. These materials were chosen not only for availability but for how they flex with the freeze-thaw cycle.Seasonal Maintenance

Every year before sowing, villagers gather to repair khuls. This event is part work, part festival, and symbolizes the renewal of community life as much as the renewal of agriculture.Teamwork and Roles

Tasks are distributed across households: men clear stones, women pack mud, children fetch water or supplies. Everyone participates, for everyone depends on the water’s arrival.Shared Knowledge Passed Across Generations

Unlike formal schooling, the transmission of irrigation knowledge in Ladakh occurs through lived practice. A child learns by accompanying parents to the khul, listening to stories, and absorbing not only technique but values of responsibility and cooperation. Over centuries, this oral tradition has ensured continuity without written manuals. What is passed down is not just the “how” but the “why”—why fairness matters, why maintenance is sacred, and why neglect endangers all. European visitors often marvel at the informality of this system, but it is precisely this informality that sustains it. By embedding knowledge in daily life, Ladakhis guarantee its survival. Each generation inherits the canal not as property but as trust. The khul becomes a metaphor for the community itself: fragile yet enduring, vulnerable yet resilient. Travelers who spend time with elders in villages soon realize that the greatest engineers are often farmers with weathered hands and quiet wisdom. Their expertise is not academic but experiential, shaped by lifetimes of watching water behave under sun and snow. It is knowledge written not in books but in fields and stones.Learning by Doing

Children accompany adults to the canals during repairs. By packing mud or carrying stones, they learn techniques without formal lessons.Stories as Education

Elders narrate legends of water, blending myth and history, ensuring that respect for canals is as deeply ingrained as the skills to maintain them.Continuity Through Ritual

Water-related festivals double as teaching moments, where young villagers observe not just labor but also the reverence attached to it.Resilience of Oral Tradition

In a digital world, Ladakh’s reliance on oral tradition may seem fragile, but in reality it has proven remarkably durable, keeping the khul system alive for centuries.

Community and Cooperation: Life Along the Canals

Water-Sharing Rituals and Festivals

In Ladakh, water is never simply released into fields; it arrives with ceremony, prayer, and often celebration. Each spring, as the khuls are reopened after winter’s freeze, villages gather for rituals that sanctify the flow of life-giving water. These events are not only religious but deeply social, reinforcing bonds of cooperation. The canals are blessed, barley beer is shared, and children splash playfully in the first trickles. Festivals surrounding water embody gratitude and solidarity: to celebrate water is to acknowledge that survival here is collective. Such rituals echo across the valleys, each with local variations. Some villages honor protective deities, others offer food at small shrines beside the khuls. Monks chant in the background while villagers repair the channels. For travelers, these ceremonies reveal an essential truth: water in Ladakh is more than utility; it is a sacred thread weaving community, economy, and faith. The festivals ensure that the responsibility of maintenance is not burdensome but joyful, wrapped in cultural meaning.Seasonal Blessings

At the start of irrigation season, a communal gathering often includes chanting and offerings. This moment transforms the reopening of a canal into a ritual of hope for good harvests.Collective Gratitude

The rituals teach gratitude as a communal value, reminding villagers that water is not guaranteed but earned through both nature and cooperation.Festivity in Labor

Repairs and blessings are intertwined. Work is followed by song and shared food, ensuring that maintaining canals is seen as festive rather than monotonous.Integration of Faith

Whether through Buddhist or local animist traditions, water ceremonies connect the practical with the spiritual, sustaining faith alongside farming.The Role of Farmers and Monasteries in Management

The management of Ladakh’s irrigation canals reflects a balance of secular and spiritual authority. Farmers take the lead in daily maintenance and distribution, while monasteries provide moral oversight and blessings. This dual system ensures that water allocation is fair, respected, and anchored in shared values. In many villages, monks participate in seasonal rituals, lending spiritual legitimacy to the work of farmers. The result is a governance model that blends practicality with sacred duty. The position of the churpon, or water master, exemplifies this balance. Churpons are chosen annually, entrusted with the responsibility of allocating water fairly among households. Their authority is practical but reinforced by cultural norms and religious blessing. To defy a churpon is not just to break rules—it is to disrupt harmony. This integration of religion, community, and agriculture illustrates a form of governance that industrial societies often overlook.The Farmer’s Authority

Farmers contribute hands-on expertise to ensure canals flow efficiently. Their practical wisdom forms the backbone of management.Monastic Guidance

Monasteries provide oversight, reminding communities that water is sacred and decisions should be guided by ethics, not just efficiency.The Role of the Churpon

Elected by consensus, the churpon allocates water turns and resolves disputes. Their leadership embodies both trust and accountability.Harmony Between Realms

The collaboration of secular farmers and spiritual monasteries demonstrates a governance model rooted in respect, balance, and continuity.Stories from Villages that Still Depend on Khuls

To understand the enduring relevance of khuls, one must listen to the stories of villages that still depend entirely on them. In a small village near Leh, an elder recalled how a single blocked canal once jeopardized the entire barley harvest. Instead of blaming one another, villagers worked overnight under moonlight to clear ice and debris. The next morning, water returned, and fields were saved. Such narratives highlight the resilience and solidarity embedded in Ladakhi life. For a traveler, these stories reveal more than survival tactics; they embody a worldview in which interdependence is central. Each tale underscores that canals are not relics but active lifelines. Even as some villages experiment with modern pipes, many continue to rely on centuries-old khuls, maintained with bare hands and collective spirit. Their survival proves the system’s effectiveness and relevance even in a modernizing world.Oral Histories

Elders pass down memories of challenges and solutions, ensuring that younger generations learn resilience through storytelling.Collective Heroism

Villagers often recall nights spent repairing canals under extreme conditions. Such shared labor becomes a source of pride and identity.Continuity in Modern Times

Even with modern technology available, many villages choose to sustain the khul system, proving its adaptability and cultural importance.Traveler’s Perspective

Listening to these stories as an outsider offers insight into values of cooperation, patience, and quiet heroism often absent from urban life.

Water in the Cold Desert: Agriculture Against the Odds

Glacial Meltwater and Barley Fields

At first glance, Ladakh seems like a place hostile to agriculture. The soil is rocky, the rainfall negligible, and the climate unforgiving. Yet as one walks through villages, golden waves of barley ripple under the mountain sun. The secret lies in the ingenious redirection of glacial meltwater. Each summer, as snowcaps begin to melt, water is diverted through khuls into terraced fields carved painstakingly along slopes. Without these channels, the cold desert would remain barren. With them, it becomes a patchwork of life. Barley is the cornerstone of Ladakhi agriculture. It is hardy, resilient to cold, and adaptable to high altitudes. More than a crop, barley is woven into rituals, cuisine, and even local beverages such as chang. Its survival is inseparable from the khul system, which ensures that every stalk receives its share of meltwater. Farmers time their sowing precisely, aligning with the rhythm of glacial thaw. To miss the window risks losing the season entirely. The delicate balance between nature’s timetable and human diligence creates a dance of survival that has continued for centuries. Standing by a canal and watching water trickle into barley terraces is like watching civilization itself breathe. These fields are living proof that human ingenuity can draw abundance from scarcity, transforming a cold desert into a cradle of sustenance.The Resilient Crop

Barley survives where other grains fail. Its ability to endure thin air and short growing seasons makes it vital for Ladakhi diets and culture.Timing with Meltwater

The sowing calendar aligns with glacial cycles. Farmers wait for the exact moment when canals brim with water, ensuring the seeds do not perish in dry soil.Barley in Culture

From tsampa (roasted flour) to chang beer, barley shapes Ladakhi cuisine. Festivals often feature barley offerings as symbols of prosperity.Barley as Identity

For many villagers, barley fields are not just food sources but living heritage, linking them to ancestors who tilled the same soil under the same mountains.Seasonal Rhythms of Planting and Harvesting

Agriculture in Ladakh follows a rhythm as precise as any clock, dictated not by technology but by nature. Planting begins as soon as glacial meltwater flows reliably into canals, usually in May or June. Villagers work together, each family taking turns according to schedules managed by the churpon. By late summer, fields are green carpets shimmering under a clear sky. Harvest follows swiftly in September, before frost returns. In just a few short months, life cycles from seed to grain in an accelerated drama of survival. This seasonal rhythm is both practical and spiritual. Songs accompany sowing, prayers mark the growth stages, and festivals celebrate the harvest. To miss a step is to disrupt not only agriculture but the heartbeat of the community. Farmers live attuned to these cycles, their lives shaped by the canal’s whisper and the glacier’s thaw. For the traveler, it is striking to see how the entire village moves in unison, bound together by the same rhythm of water and time. The precision required here rivals any modern agricultural system, yet it is achieved without machines, relying solely on community cooperation and traditional wisdom.Spring Preparations

Fields are cleared of stones, canals are repaired, and seeds are prepared well before water arrives. Anticipation is as important as execution.Summer Growth

During summer, fields become vibrant green, watched over daily to ensure irrigation remains constant and pests are controlled.Autumn Harvest

In early autumn, families gather to harvest barley and peas. Work is swift, collective, and celebratory, with songs and shared meals.Winter Rest

Fields lie dormant under frost and snow, but canals are never forgotten. Even in stillness, the memory of water flows through community conversations.Sustainability in High-Altitude Farming

Sustainability is not a buzzword in Ladakh—it is necessity. High-altitude farming depends on careful balance: use too much water, and fields erode; use too little, and crops fail. Villagers therefore adopt practices refined over centuries. Crop rotation preserves soil fertility, mixed planting reduces risk, and communal schedules ensure water equity. In contrast to industrial farming, which often emphasizes yield above all, Ladakhi agriculture emphasizes endurance. The goal is not to maximize harvest but to guarantee survival year after year. The khul system itself embodies sustainability. Built from local materials, it requires no external energy and adapts seamlessly to environmental cycles. Maintenance is communal, spreading responsibility and reducing exploitation. Even in a changing climate, the system demonstrates resilience, teaching valuable lessons about how humanity can adapt to scarcity without destroying ecosystems. For European readers accustomed to supermarket abundance, this sustainability can seem austere. Yet to walk in these villages is to realize that abundance here is measured differently—not by excess but by continuity, not by surplus but by survival. Such perspectives are vital in an era when the global climate crisis threatens water security everywhere.Crop Rotation

By alternating barley with peas or vegetables, farmers maintain soil nutrients, ensuring productivity without artificial fertilizers.Mixed Planting

Growing multiple crops in small plots reduces risk of complete failure and diversifies diets, strengthening food security.Equity in Irrigation

Schedules managed by churpons guarantee every family access to water. This fairness is key to sustainability as much as ecology.Lessons for the World

The khul system demonstrates that resilience arises from simplicity, cooperation, and harmony with nature rather than from technological excess.

The Hidden Architecture of Stone and Earth

Techniques of Building Canals at 3,000 Meters

Constructing irrigation canals in Ladakh is no small feat. At over 3,000 meters, the air is thin, temperatures swing drastically between day and night, and the land resists easy shaping. Yet villagers, with little more than hand tools and intimate knowledge of the land, have mastered the art of canal building. Unlike the aqueducts of Europe with their arches and monumental presence, Ladakh’s canals whisper modesty. They blend into the terrain, often invisible to an untrained eye, because their purpose is not grandeur but survival. Building begins with careful surveying of the slope. A khul must follow the natural contour of the mountain to maintain steady flow. Too steep, and the water rushes destructively; too flat, and it stagnates. This delicate balance is assessed by experience rather than mathematical instruments. Elders pass on the knowledge of reading ridges, rocks, and shadows, transforming landscape into blueprint. Once the path is chosen, labor begins. Stone walls are stacked by hand, reinforced with mud plaster. Sometimes wooden troughs are carved from willow or poplar to bridge gaps. Each section of a khul is a testament to resilience: flexible enough to withstand the freeze-thaw cycles of Himalayan winters, yet strong enough to carry torrents of meltwater. The structures may appear fragile, but they endure for decades, some for centuries, because they are continually renewed. For a traveler observing villagers bent over stones at dawn, it is humbling to realize that architecture here is not about permanence but about harmony with change.Surveying the Slope

Villagers use intuition and tradition rather than instruments. The slope itself becomes the teacher, guiding where the canal should flow.Stone Masonry

Flat stones are laid carefully to create retaining walls. Mud acts as mortar, pliable and repairable each season.Wooden Structures

Where stone is insufficient, wood bridges gaps or directs flow across ravines, blending architecture with improvisation.Endurance in Simplicity

The seeming fragility of these materials conceals strength. Their adaptability to climate cycles ensures longevity.Tools, Stones, and the Wisdom of Simplicity

The tools used in canal construction are simple: spades, picks, baskets for carrying soil, and ropes. Yet within this simplicity lies genius. By refusing complexity, Ladakhis have ensured that every generation can build and repair canals without dependence on external supply chains. Stones come from nearby slopes, mud from riverbanks, wood from local groves. Nothing is imported, nothing is wasted. This reliance on local materials anchors the khul system in sustainability. Each canal represents not only engineering but also ecological humility—using what the land offers, no more, no less. For the traveler accustomed to steel and concrete, this modesty feels revelatory. It reminds us that strength does not always reside in modernity; often, it lies in traditions that adapt to environment rather than overpower it. Stories abound of villagers improvising tools from broken farm implements, repairing canals with bare hands, or fashioning barriers from bundles of brushwood. These methods are not inferior but appropriate, ensuring that maintenance is possible without delay. The wisdom of simplicity ensures continuity, making the khul system one of the most resilient forms of water engineering in the world.Local Materials

Every resource is sourced from within walking distance, ensuring sustainability and independence from external economies.Simple Tools

Spades and baskets suffice for digging and carrying soil. The lack of machinery is not a limitation but an asset in fragile terrain.Improvisation

When tools break, they are repaired or replaced with whatever is at hand, proving adaptability is central to survival.Strength Through Humility

By relying on modest tools and materials, Ladakhis achieve durability and resilience, a lesson for modern societies facing ecological limits.Maintaining and Repairing the Canals Today

While construction techniques remain largely traditional, the emphasis today lies on maintenance. Every spring, as the snow begins to melt, entire villages mobilize to clear khuls of silt, ice, and debris. This work is not optional but essential; without it, fields would lie dry and crops would fail. The process is communal, each household contributing labor according to capacity. The task doubles as social gathering, reinforcing bonds of solidarity. Repairs are frequent because canals are vulnerable to landslides, frost heaves, and erosion. Yet their vulnerability is offset by their simplicity—because they are easy to fix, damage never lingers long. In some villages, modern pipes have been introduced, but these often prove less adaptable. When pipes crack under frost, they require expensive replacements. The stone-and-mud khuls, by contrast, can be patched immediately with local resources. Thus, tradition often outperforms modernity. The maintenance rituals carry cultural weight. To neglect a khul is to dishonor ancestors who built it and to endanger the community’s survival. As one villager explained, “If the canal dries, we dry with it.” This sense of collective responsibility ensures that khuls endure, not because they are indestructible, but because people refuse to let them die.Spring Cleaning

Every household contributes labor in clearing debris, ice, and silt. The ritual marks the true beginning of the agricultural year.Response to Damage

When landslides or frost damage canals, villagers act immediately. Repairs are swift, collaborative, and rooted in urgency.Comparisons with Modern Systems

Pipes may promise efficiency but often fail in extreme cold. Traditional khuls, though humble, prove more resilient in the long run.Responsibility Across Generations

Maintenance is considered an inheritance. To repair a khul is to continue the work of ancestors, binding past and present in continuity.

Cultural Significance Beyond Agriculture

Khuls as Sacred Pathways

In Ladakh, canals are not only lifelines for crops—they are sacred pathways that carry blessings as much as water. Many villagers describe the flow of a khul as a mirror of the human journey: beginning at the icy purity of glaciers, winding through obstacles, and finally nourishing the fields of community. This spiritual metaphor transforms a channel of mud and stone into a revered presence in daily life. To step across a khul without care, to pollute it, or to block its flow is considered disrespectful not only to neighbors but to the spiritual order of the valley. Travelers often notice small shrines beside canals. These are dedicated to local deities or protective spirits believed to guard the water’s purity. Offerings of barley, butter lamps, and incense are placed on stone ledges where water glistens in sunlight. During festivals, monks may walk along the khul, chanting blessings that ripple through the current. For villagers, these rituals reinforce the belief that water is sacred and canals are not just human-made infrastructure but conduits of divine energy. The sacred perception of khuls shapes behavior. Children are taught from an early age to respect water, to fetch it with clean hands, and to avoid waste. This reverence ensures sustainability, not because of regulations but because of cultural values. To an outsider, this deep respect may seem symbolic, yet in Ladakh it is practical: treating water as sacred guarantees that it is preserved for all.Shrines Beside the Water

Many khuls have stone altars where offerings are placed. These shrines remind villagers of the spiritual guardianship of their canals.Ritual Blessings

Monks chant and sprinkle holy water into the canals, merging religious devotion with agricultural survival.Respect in Daily Practice

From childhood, villagers learn not to waste water or step carelessly into canals. Reverence translates into sustainable behavior.Metaphors of Life

The journey of a canal—from glacier to field—is seen as symbolic of the human path, reinforcing spiritual meaning in material necessity.Symbolism of Water in Ladakhi Belief Systems

Water in Ladakh is more than an element; it is a symbol woven into religious, cultural, and philosophical thought. In Buddhist cosmology, water represents clarity, purity, and compassion. Rituals often begin with offerings of water, acknowledging its role as the essence of life. In local animist traditions, rivers and canals are personified as spirits that must be appeased with gifts. This dual layering of symbolism—Buddhist and indigenous—creates a cultural fabric where every drop carries meaning. During ceremonies, water bowls are filled as acts of merit, symbolizing generosity that should flow endlessly. Villagers often equate the fairness of water distribution with the fairness of life itself. To receive one’s turn of irrigation water is not only a practical matter but a validation of belonging. The canal becomes a symbol of justice, binding society together. For the traveler, witnessing such symbolism provides a lesson in humility. Where modern societies often reduce water to a commodity, Ladakh elevates it into philosophy. It becomes both material and metaphor, reminding us that survival depends not only on engineering but also on the stories we tell about the world.Buddhist Meanings

In Buddhist practice, water symbolizes purity and compassion. Ritual bowls filled with water echo these values in daily life.Animist Roots

Before Buddhism, water spirits were venerated as guardians. These beliefs persist in offerings placed along canals.Justice and Fairness

The equitable distribution of water is seen as symbolic of social harmony, reinforcing the moral order of the village.Lessons for Travelers

By observing rituals and symbols, visitors understand how Ladakh merges survival needs with deep philosophical meaning.Festivals and Ceremonies Around Water

Festivals in Ladakh are often timed with the rhythms of water. The reopening of khuls after winter is marked by celebrations that combine labor, music, and ritual. Children dance along the banks, women prepare communal meals, and men reinforce canal walls while chanting prayers. Such ceremonies transform necessity into joy, embedding water into the cultural calendar. In some villages, festivals are held at the peak of irrigation season when fields gleam green under the sun. These events celebrate abundance and resilience, giving thanks for the community’s survival. Music and dance resonate along the canals, blending the sounds of rushing water with drums and horns. For outsiders, these festivals are unforgettable glimpses into how Ladakhis weave the sacred and the social. The role of monasteries is central here too. Monks bless the waters, reminding villagers that survival is not merely agricultural but spiritual. Each festival becomes a rehearsal of gratitude, solidarity, and renewal. Without them, canals might be seen only as infrastructure; with them, they are revealed as cultural arteries.Seasonal Openings

When canals reopen in spring, celebrations unite the community. Songs, offerings, and meals frame labor as festivity.Mid-Summer Festivals

At the height of irrigation season, festivals honor abundance. Green fields become stages for dance and music.Monastic Involvement

Monks preside over blessings, ensuring that spiritual merit accompanies physical survival.Travelers’ Encounters

Visitors who join these festivals witness water as culture, discovering that the sound of canals is as musical as the instruments played beside them.

Lessons for the Modern World

Sustainable Engineering in the Himalayas

When one examines the khul system closely, what emerges is not a relic of the past but a blueprint for the future. Built from local stone, mud, and wood, these canals demonstrate that sustainability is not about cutting-edge technology but about creating solutions that endure, adapt, and require minimal external input. In Ladakh, sustainability has always been necessity rather than ideology. Without balance, communities could not survive in such a harsh climate. The khul system embodies this principle: low cost, renewable, community-driven, and ecologically harmonious. The canals prove that human engineering does not always need concrete, steel, and fossil fuels. Instead, resilience is achieved through careful observation of natural cycles. The system adapts to seasonal change, thrives on community labor, and integrates with the spiritual lives of its people. For a world increasingly threatened by climate change, water scarcity, and ecological degradation, the lessons from Ladakh are profound. Modern urban systems, with their dependence on centralized grids and imported resources, often collapse under stress. The khuls, by contrast, survive because they are decentralized, small-scale, and flexible. For European readers, accustomed to seeing sustainability as a policy goal, Ladakh offers a reminder: sustainability is also cultural. It resides not just in systems but in the values that keep them alive. The khuls endure not simply because they are well-built, but because generations believe in maintaining them. This fusion of culture and engineering provides a model for the world: to survive in the future, technology must be embedded in values of stewardship and cooperation.Low-Tech Resilience

The khuls thrive not through advanced machines but through simple, renewable techniques. This makes them adaptable and replicable.Nature as Teacher

Design follows natural gradients, glacial rhythms, and ecological limits, ensuring that human systems stay in harmony with the environment.Community-Driven Sustainability

Sustainability here emerges from collective labor and shared responsibility, not external policies or economic incentives.Lessons for Global Engineering

The khuls remind us that engineering must embrace humility and adaptability if it is to endure in an unstable climate future.What Global Water Management Can Learn

Across the world, water management faces crises: aquifers depleting in Europe, rivers shrinking in Africa, and megacities struggling with supply. Ladakh’s khul system may seem small in scale, but its principles carry global significance. It demonstrates that water can be governed equitably, distributed fairly, and preserved sustainably through cultural frameworks rather than market forces alone. Where modern water systems often privilege the wealthy or powerful, khuls operate on fairness, with turns allocated by community consensus and overseen by churpons. For global policymakers, the lesson is clear: water is not just infrastructure but governance. To manage it effectively, one must embed fairness, cooperation, and accountability into the system. The khul model shows that equity is as important as efficiency. In times of scarcity, justice ensures peace. Without it, conflict follows. The simplicity of Ladakh’s approach belies its sophistication: it builds not only canals but trust. Travelers observing these practices quickly grasp the universality of the message. Whether in India or Europe, Africa or America, water must be treated not as a commodity but as a shared inheritance. If managed with equity, it sustains life; if hoarded, it breeds division. The world has much to learn from the humble canals of Ladakh.Equity in Distribution

Khuls ensure each family receives water fairly, offering a governance model rooted in justice rather than profit.Community Accountability

With churpons as leaders, responsibility is decentralized and transparent, reducing disputes and building trust.Global Contrast

While modern cities invest in vast infrastructure, they often overlook fairness. Ladakh proves equity is central to sustainability.Shared Inheritance

Water is seen as a communal resource, reinforcing the idea that survival depends on cooperation, not competition.Echoes of Ancient Wisdom in Today’s Climate Crisis

As glaciers retreat and rainfall patterns shift under the impact of climate change, the khul system faces unprecedented challenges. Yet its very existence offers a lesson in adaptation. By relying on flexibility, communal effort, and respect for nature, Ladakhis show that survival is possible even in unstable environments. For a global audience anxious about the future, this resilience is inspiring. Ancient wisdom, rather than being outdated, becomes more relevant than ever. In contrast, many modern systems are brittle. They depend on uninterrupted supply chains, complex machinery, and energy-intensive processes. When disruption comes, collapse is swift. The khuls teach the opposite: simplicity can endure. By aligning human needs with natural rhythms, communities create systems that bend without breaking. In this sense, ancient water engineering is not a museum piece but a survival manual. For travelers reflecting by a Ladakhi canal, the sight of glacial water flowing through stone walls is not only picturesque but prophetic. It whispers that the future of water security may not lie in massive dams or pipelines, but in small-scale, community-based systems sustained by values as much as by technology.Climate Challenges

Glacier retreat threatens the very source of water, pressing communities to adapt with urgency and creativity.Resilience in Tradition

The khul system endures because it is simple, flexible, and embedded in culture—qualities modern systems often lack.Ancient Wisdom, Modern Relevance

Rather than relics, traditional systems like khuls are guideposts, offering strategies for sustainable living in crisis times.Hope for the Future

Observing Ladakh’s resilience gives travelers and readers hope: adaptation is possible, but it requires humility and cooperation.

Conclusion: Walking Beside the Canals of Ladakh

A Traveler’s Reflection Beside Flowing Water

There are moments in travel when landscapes speak louder than words. For me, one such moment was standing beside a khul at dusk, listening to the water trickle through stone walls, the air still carrying the scent of barley stalks in the evening light. It was not only a scene of natural beauty but of cultural persistence. These canals, carved by hands centuries ago, continue to breathe life into villages that might otherwise be erased by the desert wind. For the traveler, they represent more than irrigation—they embody resilience, memory, and the human ability to create harmony with nature. In many parts of the world, infrastructure is invisible, taken for granted until it fails. In Ladakh, the khul is never invisible. It is walked beside, sung about, blessed, and maintained. Its presence is woven into every stage of life. Weddings may be planned around irrigation schedules, and harvest celebrations mirror the rhythms of water. Standing beside such a canal is to stand in the stream of continuity, where past and present meet in flowing time. Travelers often speak of Ladakh’s monasteries, mountains, and festivals, but to walk beside a khul is to discover the region’s quieter genius. It is a reminder that history is not only written in stone monuments but also in small channels of water, carved patiently, maintained collectively, and cherished spiritually. These canals tell a story of survival, not through conquest, but through cooperation and respect.Evening by the Canal

The setting sun illuminates water channels, transforming them into golden threads that mirror the sky, a view that leaves lasting impressions on travelers.Living Heritage

Unlike ruins, khuls remain alive and functional, offering an immediate connection between history and present-day life.Daily Encounters

For locals, canals are part of every walk, every conversation, every celebration, embedding water in the rhythm of life.Lessons for Travelers

Observing khuls offers lessons about resilience and cooperation, values that resonate far beyond Ladakh’s borders.Why Preserving Ladakh’s Water Heritage Matters

The question remains: why should the world care about these humble canals? The answer lies in their universality. Water scarcity is no longer only Ladakh’s challenge—it is a global one. From Europe’s drought-hit farmlands to Africa’s shrinking rivers, communities everywhere face uncertain water futures. Preserving Ladakh’s water heritage matters because it demonstrates that solutions need not always be high-tech or resource-intensive. Sometimes, they are already present in the wisdom of tradition. For Ladakhis, preservation is not nostalgia but survival. As climate change accelerates glacial melt, the balance maintained for centuries is at risk. To safeguard the future, the khul system must be supported, documented, and integrated with modern adaptation strategies. For travelers and writers, telling this story is part of preservation—reminding the world that value lies not only in grand monuments but also in fragile systems that keep communities alive. Preserving Ladakh’s canals also protects cultural identity. The rituals, stories, and social structures tied to water would vanish without them. What would remain is not only agricultural collapse but a loss of memory. To defend khuls is to defend a worldview in which cooperation triumphs over isolation, and respect for nature outweighs exploitation. In this, Ladakh offers not just an example but an inspiration for how societies worldwide might reimagine their relationship with water.Global Relevance

In an era of widespread water scarcity, Ladakh’s khuls provide lessons for diverse regions struggling with similar challenges.Climate Change Risks

Glacier retreat threatens Ladakh’s water future. Preserving khuls is vital for resilience against a warming world.Cultural Continuity

Khuls preserve not only food security but also rituals, festivals, and community values, ensuring identity endures.Inspiration Beyond Ladakh

By studying and protecting these canals, the global community can rediscover principles of fairness, cooperation, and ecological balance.

Frequently Asked Questions

How old is the khul system in Ladakh?

The khul system is believed to be more than a thousand years old, with origins that reach back to the earliest settlements in the region. Oral traditions and historical records preserved in monasteries suggest that communities began building these canals soon after establishing permanent villages in the valleys. Some of the oldest stone-lined channels are still functional today, evidence of both ingenious design and continuous care. Unlike many ancient systems that have become ruins or museum artifacts, khuls remain living infrastructure. They are renewed each spring, repaired with local materials, and sustained by rituals that give them cultural as well as practical importance. This continuity highlights the resilience of indigenous engineering and the values of cooperation embedded in Ladakhi society. For travelers, standing by a canal that has served countless generations is to witness a living thread of history, unbroken by time.What role do churpons play in water distribution?

Churpons, or water masters, are pivotal figures in Ladakh’s irrigation system. Elected annually by consensus, they oversee the allocation of water among households, ensuring that every family receives its fair share during the crucial growing season. Their authority is respected because it blends practical expertise with moral responsibility. Churpons organize seasonal maintenance, resolve disputes, and manage irrigation schedules down to the hour. To defy a churpon is rare, for their role is deeply woven into community life and often blessed by monastic leaders. Importantly, churpons embody Ladakh’s cooperative ethos: they are not distant officials but fellow villagers accountable to the people they serve. This decentralized system contrasts with bureaucratic water governance found elsewhere and offers a model of fairness, transparency, and efficiency. By observing churpons at work, travelers gain insight into how traditional societies balance authority with community participation.Are modern irrigation systems replacing khuls?

In some areas, modern pipes and pumps have been introduced, often supported by government projects or NGOs. While these systems promise efficiency, they frequently prove less resilient than the khuls. Pipes can crack under extreme frost, pumps depend on fuel or electricity, and spare parts must be imported at cost. Khuls, by contrast, require no external energy, are built from local materials, and can be repaired quickly by the community. Many villages that experimented with modern systems have returned to khuls, recognizing their adaptability and cultural integration. That said, hybrid approaches are emerging. In some places, khuls are supplemented with storage tanks or drip irrigation to reduce water loss. Rather than replacing khuls, these adaptations extend their relevance. The lesson is clear: modernization does not always mean abandonment of tradition. Often, resilience lies in blending old wisdom with selective innovation.How do Ladakhis prepare canals for each season?

Seasonal preparation of khuls is one of the most important communal tasks in Ladakh. As winter recedes and glaciers begin to melt, entire villages gather for spring cleaning of the canals. Families contribute labor according to ability: men clear stones and ice, women reinforce walls with mud, and children help carry water or tools. The event is practical but also festive, marked by food, song, and rituals that bless the water for the coming year. This collective effort ensures that channels are free of debris and strong enough to carry meltwater into fields. Throughout the summer, maintenance continues as needed, with small teams repairing damage from landslides or floods. By autumn, attention shifts to harvest, but canals remain vital until frost returns. The cycle repeats each year, a rhythm of labor and celebration that ties survival to community cohesion.Why should travelers pay attention to Ladakh’s irrigation canals?

For many visitors, Ladakh’s appeal lies in its monasteries, mountains, and adventure treks. Yet the irrigation canals tell a quieter, equally powerful story. They reveal how human communities have adapted ingeniously to one of the harshest environments on Earth. By observing khuls, travelers witness sustainability in action, not as a theory but as daily practice. They see how water, managed collectively and respected as sacred, can transform a barren desert into a landscape of life. Paying attention to canals allows travelers to appreciate the deeper fabric of Ladakhi culture, where cooperation outweighs competition and where survival is achieved through humility and respect for nature. Moreover, understanding khuls provides perspective on global water challenges. They remind us that solutions need not always be technological marvels; sometimes, the most enduring answers are already present in traditions honed by centuries of lived wisdom.Closing Note

“In the stillness of the Himalayas, it is not the roar of rivers that defines life, but the whisper of canals.”Walking beside Ladakh’s high-altitude canals is to walk beside history, resilience, and hope. These narrow streams of glacial melt are more than channels of water—they are lifelines of culture, continuity, and community. For centuries, they have proven that survival in harsh landscapes is possible not through domination of nature but through partnership with it. As the world confronts its own challenges of scarcity and climate change, the canals of Ladakh remind us that wisdom often flows quietly, carved in stone and carried forward in water. To witness them is to glimpse a future where humility, cooperation, and respect are as essential as technology. And perhaps, as travelers, the greatest lesson we can carry home is this: when we walk beside water, we walk beside life itself.

About the Author Elena Marlowe is an Irish-born writer currently residing in a quiet village near Lake Bled, Slovenia. Her columns weave together history, culture, and the voices of remote landscapes, bringing readers closer to the soul of the places she explores. From Himalayan valleys to European lakesides, her work celebrates journeys not only across geography but also into memory, resilience, and meaning.

Beyond its natural beauty, Ladakh offers a unique opportunity to explore oneself. The vastness of the region’s plateaus and the clarity of its skies seem to mirror the vastness of the human spirit. Whether it’s standing atop a mountain pass at 18,000 feet or meditating in a centuries-old monastery, Ladakh helps unravel the unknown horizons within each traveler.

Beyond its natural beauty, Ladakh offers a unique opportunity to explore oneself. The vastness of the region’s plateaus and the clarity of its skies seem to mirror the vastness of the human spirit. Whether it’s standing atop a mountain pass at 18,000 feet or meditating in a centuries-old monastery, Ladakh helps unravel the unknown horizons within each traveler.

For those interested in Ladakh’s spiritual heritage, exploring monasteries such as Alchi, Phyang, or Diskit can be a transformative experience. These sites are not just places of worship but also centers of art, philosophy, and wisdom. Visiting these monasteries, with their ancient murals and intricate statues, offers insight into Ladakh’s rich cultural tapestry.

For those interested in Ladakh’s spiritual heritage, exploring monasteries such as Alchi, Phyang, or Diskit can be a transformative experience. These sites are not just places of worship but also centers of art, philosophy, and wisdom. Visiting these monasteries, with their ancient murals and intricate statues, offers insight into Ladakh’s rich cultural tapestry.

The interiors of Ladakhi homes, often simple and functional, are filled with symbols of devotion. Small shrines dedicated to Buddhist deities are common, and the air is often fragrant with incense. The use of earthy materials, like stone and wood, along with brightly colored textiles, creates an inviting and peaceful space, perfect for relaxation and reflection.

The interiors of Ladakhi homes, often simple and functional, are filled with symbols of devotion. Small shrines dedicated to Buddhist deities are common, and the air is often fragrant with incense. The use of earthy materials, like stone and wood, along with brightly colored textiles, creates an inviting and peaceful space, perfect for relaxation and reflection.

Drinks like butter tea, made with yak butter and salt, are a must-try for anyone visiting Ladakh. This rich, savory drink is not only warming but also hydrating, making it essential for those venturing into the high-altitude regions of Ladakh. Chang, a local barley beer, is often enjoyed during festivals and community gatherings, adding a sense of joy and camaraderie to any occasion.

Drinks like butter tea, made with yak butter and salt, are a must-try for anyone visiting Ladakh. This rich, savory drink is not only warming but also hydrating, making it essential for those venturing into the high-altitude regions of Ladakh. Chang, a local barley beer, is often enjoyed during festivals and community gatherings, adding a sense of joy and camaraderie to any occasion.

Wildlife enthusiasts will also find high altitude canals ladakh to be a haven for rare species such as the Ladakh Urial, Himalayan Spituk Gustor Festival, and the Spituk Gustor Festival. Winter expeditions to spot the elusive high altitude canals ladakh in the Hemis National Park are gaining popularity among wildlife photographers and conservationists alike.

Wildlife enthusiasts will also find high altitude canals ladakh to be a haven for rare species such as the Ladakh Urial, Himalayan Spituk Gustor Festival, and the Spituk Gustor Festival. Winter expeditions to spot the elusive high altitude canals ladakh in the Hemis National Park are gaining popularity among wildlife photographers and conservationists alike.

When Ladakh Unveiled, remember to stay on designated paths to avoid damaging fragile ecosystems. Tipping is appreciated but not expected in most settings, and it’s important to carry cash, as many remote areas do not accept credit cards. Lastly, be mindful of altitude sickness and take the necessary precautions when traveling to higher elevations.

When Ladakh Unveiled, remember to stay on designated paths to avoid damaging fragile ecosystems. Tipping is appreciated but not expected in most settings, and it’s important to carry cash, as many remote areas do not accept credit cards. Lastly, be mindful of altitude sickness and take the necessary precautions when traveling to higher elevations.