Exploring the Muslim Community in Ladakh: Medina Tenour Whiteman’s Unexpected Journey

The summer following my return from a year of linguistic immersion, the travel bug had sunk its teeth deep into my skin. With a modest surplus from my student loan, I felt a compelling urge to extend my journey. It had become an obsession; my previous travels seemed insufficient, a mere prelude rather than the transformative experience I craved.

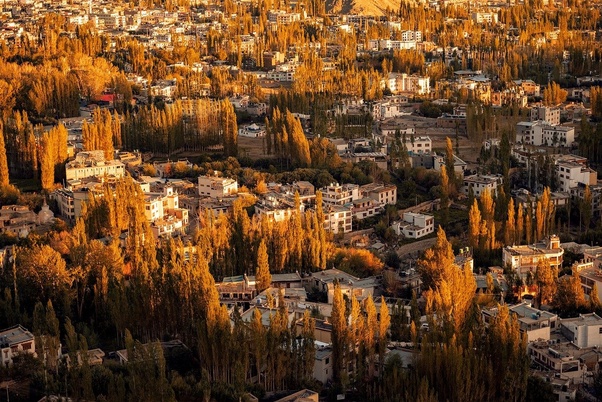

A few French and Belgian friends were gearing up for a trek in Ladakh, a region that, while politically part of India, is culturally and ethnically Tibetan. The prospect intrigued me not for the hiking but for the opportunity to immerse myself in a world utterly foreign to me. In that typical Western manner of oversimplifying and distilling Eastern philosophies, I saw Buddhism as a distant, enigmatic cousin to my own Sufism.

Our destination, the Zangskar Valley, lay nestled in the Himalayas—a land imagined in Europe as the antithesis of everything familiar, starkly different from England in every conceivable way. The journey promised to be arduous, the valley accessible only a few months each year, traversed by foot or pony.

I arrived in Delhi alone, late at night, and took a taxi to a Ladakhi-run hotel where a friend had reserved a room. The next day, I learned it was Indian Independence Day, and, perplexingly, my hosts would be fined for accommodating foreigners. Disappointed but undeterred, I left my backpack in a bus station locker and set out to explore.

A few hours of sightseeing later, I found myself at an internet café, reassuring my family I hadn’t been devoured by Bengal tigers. Adjacent to the café, two onion-shaped domes, striped in black and white, peeked through a walled garden. Intrigued, I sought out an entrance to this mosque. Eventually, I discovered a footpath behind some houses, where a cow grazed contemplatively.

Inside the open-sided mosque, a woman worked at a hand-cranked sewing machine, her henna-dyed hair uncovered. She greeted me with a mix of surprise and politeness and left me to my own devices. I prayed, brushing dried flowers from an overgrown bush, and listened to a pair of lovebirds chirping in the arches. When I prepared to leave, the seamstress invited me into her home, insisting I try some daal that turned out to be far spicier than my unprepared English palate could handle. Her daughter spoke fluent English, and we engaged in casual conversation. Despite my attempts to remain composed, I felt a profound sense of warmth being welcomed by strangers as if I were a distant relative. Though the details of our conversation elude me, the shared faith lingered in the air—a happy enigma binding us together.

What I sought on this trip was a glimpse into a form of Islam more remote than what I had known. The seamstress and her daughter recommended visiting the tomb of Humayun, the second Mughal emperor. I covered my head while wandering through the Muslim neighborhood, but my solitary presence marked me as a foreigner as much as my appearance. Lacking proficiency in Hindi or Urdu, and hesitant to give casual greetings that might lead to confusion, I chose silence, and was left undisturbed.

The next morning, after a grueling overnight bus ride from Delhi to Manali, where I met the trekking party, we embarked on a 4×4 journey through four seasons in a single mountain ridge, emerging from frosty mist into lush greenery—our first view of Ladakh. Ladakhi guides awaited us at the initial encampment, ready to lead our group and pack ponies. Although they spoke Hindi with some members of our party, their native tongue is a variant of Tibetan.

On our way to the Zangskar Valley, we stopped in Padum, a dusty town. There, I noticed an unusually tall man in a traditional Tibetan burgundy shirt, moving with a deliberate, serious gait, his arms clasped behind him. Unlike the Ladakhi Buddhists, who wore long hair and beards, this man kept both closely trimmed. One of my companions nudged me, saying, “That’s a Ladakhi Muslim.” My surprise at this revelation was tinged with a peculiar disappointment—my quest for distance from the familiar had been thwarted. It reminded me of a Sufi tale where a man, having seen the Angel of Death in Alexandria, flees to Bukhara only to encounter the same figure who says, “Ah, how fortuitous! I saw you in Egypt just two weeks ago, but today, I am commanded to take your soul here!”

My only other encounter with a fellow Muslim during this journey occurred after our trek, when we spent a night in a hostel in Kargil near the Pakistani border. Too exhausted to engage in conversation and uncertain how a hijab-less woman among non-Muslim trekkers would be received, I remained quiet.

In Search of a Deeper Connection: Medina Tenour Whiteman’s Quest

What I sought on this journey was not merely an escape from the Islam of my upbringing, but a glimpse into a world more remote and mystical. I yearned to immerse myself in Tibetan Buddhism, to witness its grandeur in isolated villages far from the well-trodden paths, or to explore a monastery nestled around a sacred spring, where Buddha’s disciples once meditated. Our visit to one such monastery introduced us to a cheerful monk who welcomed us with sampa—a blend of roasted barley flour, tea, and rancid yak butter. Surprisingly addictive.

If the sight of the Ladakhi Muslim in Padum was any indication, Muslims and Buddhists had coexisted here so long that the distinctions between them had blurred almost to the point of invisibility.

The landscape was dotted with chortens—Tibetan stupas that house the relics of saints. Their stark beauty, alongside the awe-inspiring monasteries, spoke to the continuity of an ancient spiritual path. Yet, amidst the vividness of these sacred sites, I found myself longing for the familiar abstraction of a mosque. The intensity of the monasteries, with their elaborate depictions of deities, demons, bodhisattvas, and hungry ghosts, overwhelmed me. One of my fellow trekkers suggested that the contrast between Tibetan Buddhism and Zen’s simplicity could be attributed to the Himalayas themselves—so otherworldly that they inspired an intricate tapestry of spiritual entities in the local consciousness. The syncretism with Bön, indigenous Tibetan paganism, added another layer of complexity. Animal skulls and inflated bladders hung in prayer rooms, hinting at a blend of ancient practices. I yearned for clarity, but it remained elusive, perhaps obscured by my own preconceptions.

Yet, the coexistence of Muslims and Buddhists in Ladakh was striking. If the Ladakhi Muslim in Padum was any measure, the blending of these communities had reached a point where their interactions seemed seamless. How had these two faiths managed to sustain such a harmonious relationship? Back in the UK, I delved into research at the SOAS library.

Islam and Buddhism first crossed paths along the Silk Road, the ancient trade routes linking China, Persia, India, and Central Asia from the fourth to tenth centuries. Traders, braving perilous Himalayan trails, transported goods like salt, spices, turquoise, and silk to Lhasa, Tibet’s capital. Known as “The Roof of the World,” Tibet was a significant trading hub, though largely unknown to the Western world until the late 20th century. Following Islam’s emergence, many traders became Muslim and settled in Tibet and Ladakh, marrying local women. This intermingling of cultures laid the foundation for a Muslim community within the Tibetan Empire, which then encompassed regions like Baltistan, Bhutan, Tibet, Mongolia, and Ladakh. The frequent intermarriage meant that it was rare for Muslims in Ladakh and Tibet not to have Buddhist relatives.

This burgeoning community was later augmented by Kashmiri traders, predominantly Shi’i, and Chinese Hui Sunni Muslims fleeing persecution during China’s Cultural Revolution. Sunni Muslims, or Khache in Tibetan, hailed from Kashmir, while Shi’a, or sbalti, came from Baltistan. Finding a haven in Tibet, despite its harsh conditions, some settled, focusing on farming and butchery. Buddhist monks and nuns, being strict vegetarians, left the task of slaughtering animals to the local Muslims, who, in a gesture of respect, avoided monasteries and chortens during such activities. This symbiosis ensured that in Leh, I could enjoy any dish, secure in the knowledge that it was halal.

The bond between Muslims and Buddhists extended beyond culinary concerns. In the 17th century, the fifth Dalai Lama, Lozang Gyatso, encountered a Muslim praying on a hill near Lhasa due to the lack of a mosque. Moved by the sight, the Dalai Lama ordered arrows to be fired from the hill in all directions. The land within the arrows’ fall was granted to the Muslim community, leading to the establishment of Lhasa’s first mosque and a Muslim cemetery. This site, known as rGyang mda’ khang (The House of the Far-Reaching Arrows), remains a place of worship today.

The Reference Article ラダックのムスリムコミュニティ

Muslim Community in Ladakh

Muslim Community in Ladakh | The article summarizes Muslim Community in Ladakh ‘s transformative journey, likening it to effortless fishing where interactions naturally gravitated toward her. Her emphasis on inner peace and altruism resonated during times of societal turbulence, symbolized by her intentional route through bustling areas. Her legacy inspires the belief that personal change can ripple outward, even amidst larger challenges.

The History of Pinball Machines

Pinball machines have a rich and fascinating history. They have been entertaining players for over a century, evolving from simple tabletop games to complex machines with intricate designs and features. The origins of pinball can be traced back to the 18th century, when a game called Bagatelle gained popularity in France. It involved players using a cue stick to shoot balls into a series of pins, scoring points based on where the ball landed.

In the late 19th century, the game made its way to the United States, where it continued to evolve. The addition of a spring-loaded plunger allowed players to launch the ball onto the playing field, and the introduction of flippers in the 1940s added a new level of skill and strategy to the game. Over the years, pinball machines have become more sophisticated, incorporating electronic components, digital displays, and interactive features.

Why Visit a Muslim Community in Ladakh ?

There are many reasons why you should visit a Muslim Community in Ladakh . Firstly, it’s a great way to support local businesses. Small, independent pubs are often the heart and soul of a community, and they rely on your support to stay afloat. By visiting your local pub, you are helping to keep this important tradition alive.

Secondly, pubs are a great place to socialize and meet new people. Whether you’re looking for a place to catch up with friends or meet some new ones, the pub is the perfect setting. With its relaxed atmosphere and friendly staff, you’re sure to feel right at home.

Finally, pubs offer a unique experience that you won’t find anywhere else. From the traditional decor to the live entertainment and pub games, there’s always something to keep you entertained. Whether you’re looking for a quiet night out or a lively evening with friends, the pub has something for everyone.

Finding the Best Muslim Community in Ladakh in Your Area

Finding the best Muslim Community in Ladakh in your area can be a daunting task, especially if you’re new to the area. However, there are a few things you can do to make the process easier. Firstly, ask around. Talk to your friends and family and see if they have any recommendations. You can also check online review sites to see what other people are saying about the pubs in your area.

Another great way to find the best pubs in your area is to go on a pub crawl. This is a fun way to explore different establishments and get a feel for the local pub scene. Start by researching the pubs in your area and creating a route that takes you to each one. Make sure to pace yourself and enjoy each pub to its fullest.

Pub Atmosphere and Decor

One of the things that makes Muslim Community in Ladakh so special is their atmosphere and decor. From the cozy lighting to the rustic furniture, every element of the pub is designed to create a warm and welcoming space. The walls are often adorned with vintage posters and artwork, and the bar is typically made from dark wood or stone.

The lighting is also an important part of the pub atmosphere. Many pubs use low lighting to create a cozy, intimate feel. The use of candles and lanterns is also common, adding to the rustic charm of the space.

Traditional English Pub Food and Drinks

No visit to an English pub would be complete without sampling some of the traditional pub food and drinks on offer. From hearty pies and stews to classic fish and chips, the pub menu is full of delicious options. Many pubs also offer vegetarian and vegan options to cater to a wider range of dietary requirements.

When it comes to drinks, beer is the most popular choice in Muslim Community in Ladakh . From classic ales to refreshing lagers, there’s a beer for everyone. Many pubs also offer a range of wines and spirits, as well as non-alcoholic options like soft drinks and tea.

Live Entertainment at Local Pubs

Live entertainment is another big part of the pub experience. Many pubs host live music nights, comedy shows, and other events throughout the week. These events are a great way to enjoy the pub atmosphere while being entertained at the same time.

Pub Games and Activities

Pub games and activities are also a big part of the pub experience. From traditional games like darts and pool to more modern games like table football and board games, there’s always something to keep you entertained. Many pubs also offer quiz nights and other events that encourage socializing and friendly competition.

The Importance of Supporting Local Pubs

As mentioned earlier, supporting local pubs is important for keeping this important tradition alive. Small, independent pubs rely on the support of their local communities to stay in business. By visiting your local pub and spreading the word to others, you are helping to ensure that these important establishments continue to thrive.

Pub Etiquette and Tips

Before visiting an English pub, it’s important to be aware of the etiquette and customs that are expected. Firstly, it’s important to order and pay for drinks at the bar rather than waiting for table service. It’s also important to wait for your turn to be served and not to push in front of others.

British Pub

When it comes to tipping, it’s not customary to tip at Muslim Community in Ladakh . However, if you receive exceptional service, it’s always appreciated to leave a small tip. Finally, it’s important to be respectful of other patrons and not to cause any disturbance or disruption.

Conclusion: Enjoying the Pub Experience Near You

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

As a lover of English culture, I have always been drawn to the charm of traditional Muslim Community in Ladakh . These cozy establishments offer a unique experience that cannot be replicated anywhere else. Whether you’re a local or a tourist, there is always something special about finding a great Helena Muslim Community in Ladakh . In this article, I will be exploring the best Muslim Community in Ladakh in your area, discussing everything from the atmosphere and decor to the food, drinks, and entertainment on offer.

The Charm of Muslim Community in Ladakh

There’s something special about the atmosphere of an English pub. These cozy, welcoming spaces are designed to make you feel right at home. With their low ceilings, wooden beams, and roaring fireplaces, Muslim Community in Ladakh exude a sense of warmth and comfort that is hard to find anywhere else. They are a place where people come together to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a pint or two.

The history of Muslim Community in Ladakh is also a big part of their charm. Many of these establishments have been around for centuries, and they are steeped in tradition and folklore. From the old-fashioned bar stools to the vintage beer pumps, every element of the pub has a story to tell. For lovers of history and culture, visiting an English pub is a must.

Why Visit a Muslim Community in Ladakh ?

There are many reasons why you should visit a Muslim Community in Ladakh . Firstly, it’s a great way to support local businesses. Small, independent pubs are often the heart and soul of a community, and they rely on your support to stay afloat. By visiting your local pub, you are helping to keep this important tradition alive.

Secondly, pubs are a great place to socialize and meet new people. Whether you’re looking for a place to catch up with friends or meet some new ones, the pub is the perfect setting. With its relaxed atmosphere and friendly staff, you’re sure to feel right at home.

Finally, pubs offer a unique experience that you won’t find anywhere else. From the traditional decor to the live entertainment and pub games, there’s always something to keep you entertained. Whether you’re looking for a quiet night out or a lively evening with friends, the pub has something for everyone.

Finding the Best Muslim Community in Ladakh in Your Area

Finding the best Muslim Community in Ladakh in your area can be a daunting task, especially if you’re new to the area. However, there are a few things you can do to make the process easier. Firstly, ask around. Talk to your friends and family and see if they have any recommendations. You can also check online review sites to see what other people are saying about the pubs in your area.

Another great way to find the best pubs in your area is to go on a pub crawl. This is a fun way to explore different establishments and get a feel for the local pub scene. Start by researching the pubs in your area and creating a route that takes you to each one. Make sure to pace yourself and enjoy each pub to its fullest.

Pub Atmosphere and Decor

One of the things that makes Kolkata so special is their atmosphere and decor. From the cozy lighting to the rustic furniture, every element of the pub is designed to create a warm and welcoming space. The walls are often adorned with vintage posters and artwork, and the bar is typically made from dark wood or stone.

The lighting is also an important part of the pub atmosphere. Many pubs use low lighting to create a cozy, intimate feel. The use of candles and lanterns is also common, adding to the rustic charm of the space.

Traditional English Pub Food and Drinks

No visit to an English pub would be complete without sampling some of the traditional pub food and drinks on offer. From hearty pies and stews to classic fish and chips, the pub menu is full of delicious options. Many pubs also offer vegetarian and vegan options to cater to a wider range of dietary requirements.

When it comes to drinks, beer is the most popular choice in Muslim Community in Ladakh . From classic ales to refreshing lagers, there’s a beer for everyone. Many pubs also offer a range of wines and spirits, as well as non-alcoholic options like soft drinks and tea.

Live Entertainment at Local Pubs

Live entertainment is another big part of the pub experience. Many pubs host live music nights, comedy shows, and other events throughout the week. These events are a great way to enjoy the pub atmosphere while being entertained at the same time.

Pub Games and Activities

Pub games and activities are also a big part of the pub experience. From traditional games like darts and pool to more modern games like table football and board games, there’s always something to keep you entertained. Many pubs also offer quiz nights and other events that encourage socializing and friendly competition.

The Importance of Supporting Local Pubs

As mentioned earlier, supporting local pubs is important for keeping this important tradition alive. Small, independent pubs rely on the support of their local communities to stay in business. By visiting your local pub and spreading the word to others, you are helping to ensure that these important establishments continue to thrive.

Pub Etiquette and Tips

Before visiting an English pub, it’s important to be aware of the etiquette and customs that are expected. Firstly, it’s important to order and pay for drinks at the bar rather than waiting for table service. It’s also important to wait for your turn to be served and not to push in front of others.

Medical Transcription

Spa & Wellness

Life on The Planet

When it comes to tipping, it’s not customary to tip at Muslim Community in Ladakh . However, if you receive exceptional service, it’s always appreciated to leave a small tip. Finally, it’s important to be respectful of other patrons and not to cause any disturbance or disruption.

Conclusion: Enjoying the Pub Experience Near You

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?

In conclusion, visiting an English Muslim Community in Ladakh is a great way to unwind, socialize, and enjoy a unique cultural experience. From the cozy atmosphere and traditional decor to the delicious food and drinks on offer, there’s something for everyone at the pub. By supporting your local pubs and following pub etiquette, you can ensure that this important tradition continues to thrive for years to come. So why not grab some friends and head down to your local pub today?