Introduction — Stones That Tell Stories

The first time I saw Basgo Fort, it didn’t look like a fort at all. There were no polished courtyards, no sweeping staircases, no fairy-tale towers like the ones I’ve walked through in France or Austria. Instead, it clung to the cliffs like a weathered prayer—mud-brick walls etched by time, a landscape more silence than structure. And yet, I knew instantly: this was not emptiness. This was memory pressed into stone.

Coming from the Netherlands, where castles stand as proud reminders of royal dynasties and European might, I had always seen them as symbols of control—built to assert, to defend, and to dazzle. In Ladakh, however, the forts seem to whisper rather than shout. They blend into the mountains. Their authority is quiet, shaped not only by politics, but by wind, sky, and the teachings of Buddhism.

In this column, I want to take you on a journey—not just across continents, but through time and meaning. We will explore castles of the world, from the moated palaces of England to the romantic ruins in Spain, and then return to Ladakh’s lesser-known bastions like Leh Palace and Zorawar Fort. This isn’t a checklist of “must-see sites.” This is an invitation to feel history beneath your fingertips. To question what it means to protect something. To ask how architecture speaks differently across landscapes and belief systems.

If you’re reading this from Europe, I imagine you’ve visited a castle—or ten. But have you ever thought about how those turrets and drawbridges compare to a hilltop fort in the Himalayas, built not to impress the eye, but to outlast the elements? Have you ever wondered why castles were painted with stories of saints and conquest, while Ladakhi forts are crowned with chortens and prayer rooms?

This is a tale of contrasts—and common threads. Of how stones become symbols. Whether molded by feudalism or forged in the isolation of high-altitude trade routes, both castles and forts stand as testaments to human resilience. And perhaps, when seen together, they tell us something more profound: that every civilization, no matter how distant or different, builds to remember, to resist, and to reach toward something greater.

Let us begin.

Castles and Forts: More Than Just Defensive Structures

What Defines a Castle? A European Legacy of Power and Prestige

When Europeans think of a castle, they often imagine a silhouette rising from green hills: turrets, high walls, a drawbridge perhaps, and a flag fluttering in the breeze. These structures, built between the 9th and 16th centuries, were far more than military bastions. They were symbols of feudal hierarchy, of dynastic power, and often of aesthetic ambition.

In France, I once stood inside the Château de Chambord—an architectural ode to symmetry and splendor, built more for the gaze of courtiers than the threats of siege. In contrast, Scottish castles like Dunnottar cling defiantly to cliffs, their design raw, muscular, and exposed to the sea winds. Whether built in limestone, granite, or sandstone, these castles were strategic statements and cultural artifacts.

The castle, in essence, was a hybrid: part palace, part fortress. It protected, yes, but it also dazzled. It hosted banquets, stored wealth, and stood as a physical manifestation of divine right and noble privilege. Religious chapels within the walls, stained glass windows depicting saints and battles, and heraldic symbols painted in grand halls—everything in the medieval castle spoke the language of both authority and aspiration.

As a regenerative tourism consultant, I often ask: what stories do these walls choose to tell, and which ones do they silence? European castles, for all their beauty, also tell a tale of exclusion, hierarchy, and conquest. Understanding that complexity is vital—not just for tourists, but for those who preserve and interpret heritage today.

What Makes a Fort a Fort? The Strategic Simplicity of Ladakh’s Stone Sentinels

And then there are Ladakh’s forts—starkly different in tone, scale, and intent. At first glance, they might appear rudimentary to a European eye. No sculpted gardens. No vaulted chapels. Yet within their silence lies a deep wisdom. These forts were built not for show, but for survival.

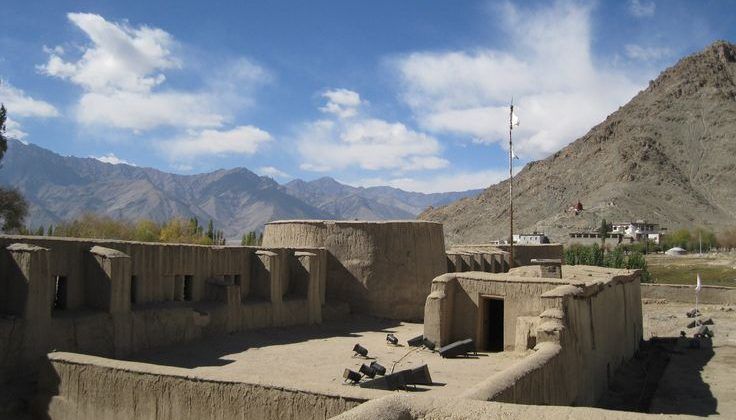

Take Zorawar Fort in Leh, for instance. Constructed in the 19th century by General Zorawar Singh, it lacks the ornamental flair of European strongholds. Instead, it is rugged, utilitarian—designed to withstand Ladakh’s biting winters and turbulent geopolitics. Its architecture is defensive in the purest sense: thick mud-brick walls, narrow entryways, and vantage points built into the hills to monitor caravan routes along the Silk Road.

Basgo Fort, crumbling and sun-bleached, once served as both spiritual center and stronghold. Unlike European castles that separate sacred from secular, Ladakhi forts often include gompas—Buddhist temples—within their grounds. This fusion of fortification and faith reveals a worldview where protection is not only physical, but also metaphysical.

There is a humility in these constructions. They are neither boastful nor imperial. They exist in dialogue with the mountains, often built from the same earth they stand upon. In that sense, Ladakh’s forts feel less like interruptions and more like continuations of the landscape itself.

To compare castles and forts is not to rank them, but to read two different dialects of the same architectural language—one rooted in display and domination, the other in resilience and reverence.

Shaped by Landscape: The Role of Geography and Environment

Castles in Verdant Valleys vs. Forts on Wind-Blasted Ridges

In the heart of Bavaria, castles rise from forested hills like mirages—wrapped in mist, framed by alpine lakes, and flanked by whispering trees. These places feel almost dreamlike, protected not only by stone walls but by the natural softness of their surroundings. Neuschwanstein, perhaps Europe’s most photographed castle, isn’t just a monument to Romanticism; it’s also a monument to a very particular kind of landscape—one that invites beauty as a strategy of power.

Geography is not a backdrop. It is a character. A collaborator. A constraint. In Europe, castles were often placed in locations that allowed for both defense and access to fertile land, water routes, and trade roads. Rivers like the Loire or the Rhine didn’t just nourish crops—they nourished influence. The gentle climate, predictable seasons, and fertile valleys enabled a certain architectural ambition. Walls could rise higher. Interiors could be more ornate. Gardens could bloom.

Now, picture Ladakh. The wind cuts like a blade. Oxygen is scarce. The land is not green, but rust-colored, bone-dry, and jagged. Here, forts don’t nestle into valleys; they cling to cliffs, as if defying gravity and reason. From the top of Basgo Fort, I saw nothing but earth and sky. No forests. No rivers. Just silence and stone. And yet, that silence held centuries of stories.

Ladakh’s environment imposes its own logic. Forts must be compact, because hauling material up a 3,500-meter slope is no small feat. They must resist not only invasion, but altitude, wind shear, landslides, and freezing temperatures. Construction uses local materials—mud, stone, and sun-dried bricks—because nothing else survives. Walls are thick not only to withstand attack, but to insulate against Himalayan nights.

And still, there’s beauty. A raw, honest kind of beauty. No gilded windows or sprawling terraces, but a kind of sacred geometry in the way the structures mirror the contours of the mountains. They weren’t built to dominate nature, but to survive within it.

When visitors from Europe encounter these sites, I often see a quiet awe in their eyes. Not because the forts are grand, but because they are improbable. And in that improbability lies their truth. The contrast between lush European valleys and Ladakh’s wind-blasted ridges is not merely visual—it’s philosophical. One landscape nurtures opulence. The other, resilience. Both tell us something vital about what it means to build—and to endure.

Culture Embodied in Stone: Religion, Art, and Rituals

Cathedrals, Chapels, and Chivalry: The Christian Imprint on Castles

In Europe, to walk into a castle chapel is to step into a world where stone breathes scripture. It’s easy to forget, surrounded by armor displays and banquet halls, that castles were also sacred spaces. Nearly every major European castle included a private chapel—some grand like the Sainte-Chapelle within the Conciergerie in Paris, others modest and hidden in towers. But all served a purpose beyond prayer. They symbolized divine right, reinforced the ruler’s authority, and sanctified war itself.

I recall visiting Hohenzollern Castle in Germany, where the stained glass windows didn’t just tell biblical stories—they told the story of lineage. Genealogy, piety, and sovereignty were interwoven. Even the very layout of castles was often influenced by Christian cosmology: east-facing chapels, cruciform halls, and iconography that reminded visitors—and residents—that power was ordained from above.

Art was not decorative—it was declarative. Murals of saints, relic chambers, and carved angels adorned interiors, turning the fortress into a heavenly fortress. Chivalric codes were preached as moral guides, tightly binding religious virtue with knightly valor. This fusion of Christianity and architecture helped transform the castle into a tool of both defense and devotion.

The religious imprint on castles, particularly during the Crusades and the Inquisition, also reveals darker truths—how faith was institutionalized, weaponized, and immortalized in stone. As a cultural analyst, I find these tensions as compelling as the beauty they produced.

Chortens, Gonpas, and Muraled Walls: Buddhist Spirituality in Ladakhi Forts

In Ladakh, religion is not enclosed in chapels. It seeps into walls, flows through corridors, and flutters in the wind. The presence of chortens (stupas), prayer wheels, and ancient gonpas (monasteries) in and around forts makes it clear: here, the spiritual and the strategic were never divided.

At Basgo Fort, I found a small Lhakhang—its faded murals depicting fierce protector deities and serene bodhisattvas, still intact after centuries. Unlike the stained-glass grandeur of Europe, these paintings feel intimate, almost whispered. They don’t seek to impress—they seek to remind. That life is impermanent. That power must be tempered by compassion. That fortification, too, can be sacred.

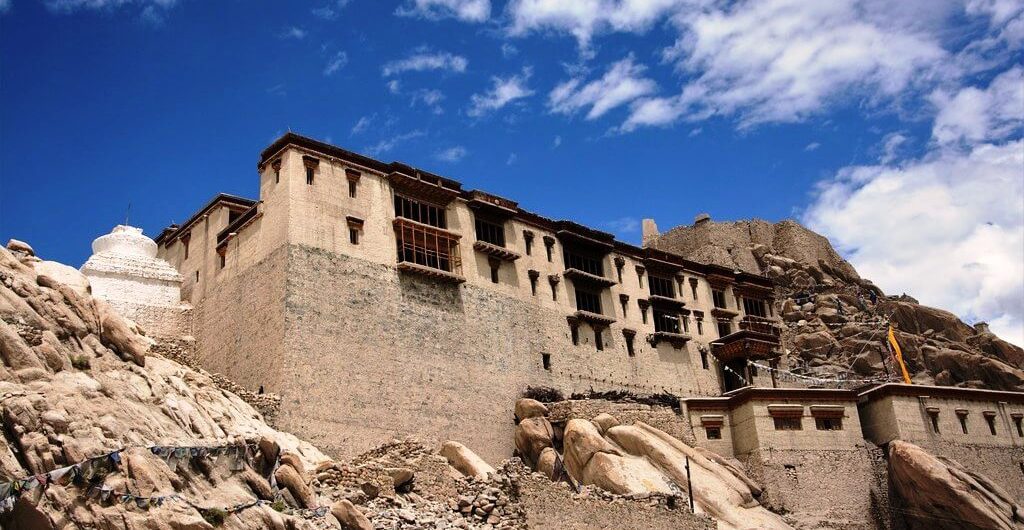

Leh Palace, which dominates the city skyline like a timeworn sentinel, contains within it small prayer rooms where butter lamps are still lit. Visitors often overlook these quiet corners. But to me, they hold the soul of the structure. Unlike European castles, where sacred spaces are often central and lavish, Ladakhi forts hide them like treasures—revealing them only to those who pause and look closely.

This integration of spirituality is not accidental. In the harsh landscape of Ladakh, survival has always depended on harmony—with nature, with neighbors, and with the unseen. Forts here were not just built to repel invaders—they were built to hold community, preserve faith, and offer protection on every level: physical, cultural, and spiritual.

If castles in Europe are monuments to man’s control over land, Ladakh’s forts feel like offerings to something greater than man. In both cases, belief is embedded in architecture. But the way it manifests—grand vs. humble, declarative vs. meditative—reveals how differently civilizations answer the same question: how should power and faith coexist?

Material Culture: What the Walls Were Made Of

What a building is made of says as much about a place as its language or cuisine. The material is never just functional—it is cultural. It’s the handshake between environment and human need. When you run your hand along a castle wall in Scotland, you feel cold granite pulled from ancient hills. In southern Spain, the Alhambra’s walls whisper with the porous coolness of red sandstone and clay. Across Europe, the palette of castle construction shifts with the soil and stone beneath the builder’s feet.

In the Loire Valley of France, castles like Chenonceau and Amboise are made of tuffeau limestone—a pale, almost chalky stone that catches the light and allows for elaborate carvings. These castles glow at sunset, reflecting not just light, but legacy. In contrast, the dark basalt stones of Ireland’s Bunratty Castle seem to soak up history, each block heavy with storm and story.

These material choices were both practical and political. Durable stone meant longevity—an assertion of permanence. Imported marble, when used, declared wealth and global reach. Even the color of the rock could signify regional identity or dynastic pride. But perhaps most importantly, European castle architecture was about defying nature: taller, grander, more symmetrical than the chaotic land around it.

Ladakh tells a different story. Here, fort walls are not statements of domination but of coexistence. The materials are humble: sun-dried mud bricks, locally gathered stones, wood from distant valleys. These were not chosen for grandeur, but for logic—for survival. In high-altitude conditions where winters bite and roads are often impassable, what you build with must come from what you have.

Take Leh Palace. Built with rammed earth and timber, its walls insulate against cold, withstand seismic activity, and blend seamlessly with the brown mountains around it. From a distance, the palace doesn’t rise above the land—it emerges from it. This is the essence of vernacular architecture: building in conversation with place, not in defiance of it.

What struck me most, as someone who has consulted on eco-sensitive construction projects across South America, is how inherently sustainable these Himalayan forts are. Before “green building” became a buzzword, Ladakh was already practicing it—by necessity, not by design. Local materials. Minimal waste. Passive insulation. Reusability.

In today’s climate-aware world, there’s something profoundly inspiring about that. It makes me wonder: what if we stopped looking at old structures as relics, and started seeing them as guides? What if the path to the future was, quite literally, built into the past?

Gender, Labor, and Power: Who Built and Who Inhabited These Fortresses?

It’s easy to romanticize castles and forts when looking only at the façades. Grand silhouettes against dramatic skies. Stone staircases worn smooth by the feet of history. But behind every arch and rampart lies another story—one not of kings and generals, but of laborers, servants, women, and unnamed artisans who left no signature, only structure.

In Europe, castle construction was often a state or church-funded endeavor, executed by a complex web of masons, quarrymen, carpenters, blacksmiths, and sometimes prisoners or indentured peasants. At sites like Warwick Castle or Edinburgh, one can still see the grooves carved by hammer and chisel. But the names of those hands? Almost always lost to time.

Women, though rarely allowed to design or build, inhabited these spaces as queens, ladies-in-waiting, healers, and—more invisibly—as laundresses, cooks, and nannies. Their daily labor sustained the beauty and functionality of the castle. While romantic tales paint women as damsels gazing from towers, reality speaks of endurance, skill, and unseen contributions. Power in castles was gendered, yes—but not always passive.

Now turn to Ladakh. While the forts here are smaller in scale, their human stories are just as layered. Oral histories speak of entire villages gathering to build walls before winter arrived. Construction wasn’t always commissioned by royalty—it was often communal, even spiritual. The line between labor and ritual blurred. Building a fort near a monastery meant aligning with astrology, offering prayers before laying foundations, and sharing resources with neighbors.

At Zorawar Fort, local stonecutters and craftspeople were enlisted during Dogra expansion. Some accounts mention forced labor under military governance. At Leh Palace, women from nearby villages carried water and clay during construction, their efforts unrecorded but essential. This silence in historical record is not absence—it is erasure.

Who lived in these forts? Not just rulers and monks, but families, guards, scribes, artisans. The rooms of Leh Palace, now empty, once echoed with prayers, politics, and meals shared in cold mornings. In both European and Ladakhi contexts, power was embedded in walls—but so was life. Messy, ordinary, and deeply human life.

As someone who works in regenerative tourism, I believe storytelling must include the full spectrum of history—not just those who ruled, but those who built and served. Only then can we look at these majestic structures and see them clearly—not just as symbols of power, but as living testimonies to collective effort, gendered labor, and social complexity.

Forts and Castles in the Modern Eye: From Ruin to Revival

European Castles as Tourist Icons and Wedding Venues

Let’s be honest: in Europe today, castles have become stage sets for modern dreams. Some host operas under the stars; others double as five-star hotels, museums, or fairy-tale wedding venues. I once attended a climate leadership summit held in an Austrian castle where the walls, once defensive, now echoed with debates about resilience and sustainability. The irony wasn’t lost on me.

From Neuschwanstein in Germany to Château de Chillon in Switzerland, many European castles are now among the top tourist attractions in their regions. They draw millions each year—visitors seeking beauty, nostalgia, history, or Instagram-perfect moments. Entire economies have developed around their preservation and presentation.

But with tourism comes tension. The need to attract crowds often clashes with the responsibility to protect. Heritage becomes spectacle. Authenticity is sometimes traded for accessibility. And yet, one cannot deny that this visibility has preserved countless sites that might otherwise have crumbled. Europe has invested heavily in restoration, supported by government grants, UNESCO, and public-private partnerships.

The question becomes: can we love these structures without consuming them? Can we engage with them not only as destinations but as dialogues—between past and present, memory and marketing?

Ladakh’s Forts: Heritage at Risk or Opportunity for Regenerative Tourism?

In Ladakh, the story is less polished—and perhaps more urgent. Many forts remain off the radar of global tourism. Some are in ruins, threatened by erosion, neglect, and climate change. Others—like Leh Palace—have seen partial restoration by the Archaeological Survey of India, but remain under-visited compared to monasteries or trekking trails.

And yet, there’s immense potential here. Ladakh’s forts are raw, powerful, and largely uncommercialized. They offer not only historical insight but also a sense of place that cannot be replicated. To walk through the sun-cracked corridors of Basgo or to stand atop the windswept ramparts of Zorawar Fort is to connect with a version of heritage that is quiet, dignified, and alive.

The key is regenerative tourism. Not just visiting, but restoring. Not extracting, but exchanging. Local communities should lead the process—offering homestays, guided walks, storytelling sessions, and traditional food around these forts. Visitors, in turn, contribute not only money but respect, dialogue, and visibility.

One inspiring example is the village-led initiative near Basgo, where locals have begun offering interpretive tours rooted in oral history and ecological awareness. There’s also growing interest from conservation architects to use ancient building techniques in restoring these sites—mud plaster, hand-cut stone, natural drainage systems.

Unlike their European counterparts, Ladakh’s forts have the advantage of starting fresh—not weighed down by mass tourism, but ready to be shaped by thoughtful travel. If we act with care, these sites can become more than ruins. They can become bridges—between past and future, visitor and host, memory and stewardship.

Personal Reflection — What These Walls Whisper to Me

Somewhere between the wind-scoured cliffs of Basgo and the manicured lawns of Chenonceau, I began to hear the stones speaking. Not in language, but in presence. In texture. In silence. And what they whispered wasn’t grandeur or glory—it was memory. Fragile, layered, unfinished.

Castles and forts, across continents, were built to endure. But more than that, they were built to be seen. To mark space. To contain power. And in doing so, they became mirrors of the societies that made them. Europe’s castles speak of dynasties and divine right, of symmetry and spectacle. Ladakh’s forts, on the other hand, speak of survival and spirit, of adaptation rather than assertion.

And yet, they share something deeply human: the need to belong. The need to hold onto something as time rushes past. Whether it’s a carved stone lion on a Scottish battlement or a prayer flag fluttering over a Ladakhi parapet, these symbols remind us that our ancestors also longed to leave a mark, to protect what mattered, to live beyond themselves.

As a European walking through Ladakh for the first time, I found myself humbled. These forts did not ask to be admired. They asked to be remembered. To be listened to. And perhaps, to be reimagined—not only as historical landmarks, but as active agents in the present: educating, uniting, regenerating.

If you, dear reader, have ever wandered through a crumbling watchtower or leaned against a castle wall wondering what lives passed before you, then you already know. Architecture is not just form—it’s feeling. And in that feeling lies the opportunity to not only visit, but to connect.

Let the next time you stand before a fortress—whether in the Alps or the Himalayas—be a moment of quiet recognition. Not just of difference, but of kinship. For though built oceans apart, the castles of the world and the forts of Ladakh are bound by the same invisible mortar: the human instinct to remember, to protect, and to dream in stone.

About the Author

Born in Utrecht, Netherlands and currently living on the outskirts of Cusco, Peru, Isla Van Doren is a regenerative tourism consultant with over a decade of experience exploring the intersection of ecology, culture, and heritage preservation.

With a background in cultural anthropology and environmental policy, her writing balances academic insight with poetic intuition—using data to ground her ideas, and emotion to elevate them. She has worked on sustainable tourism initiatives in the Andes, Patagonia, and Bhutan, bringing a global lens to every local story.

This journey to Ladakh marks her first encounter with the Indian Himalayas. What captivates her most is not just the region’s stark beauty, but the way memory lives in its architecture, and how it contrasts with the fortified legacies of Europe she knows so well.

Through comparative analysis and storytelling, she invites readers to see beyond stone and structure—to consider the cultures that built them, and the futures they may inspire.