A Tale of Two Trails

The sun was sinking behind the rolling hills of northern Spain, its golden light stretching across the cobbled pathways of the Camino de Santiago. My boots, worn but faithful, scraped against the stone as I traced the steps of millions before me—pilgrims from a thousand years of history. The scent of freshly baked bread wafted from a village bakery; a group of hikers clinked glasses in a plaza, celebrating another day of walking. The rhythm was familiar. The walk was as much about endurance as it was about reflection.

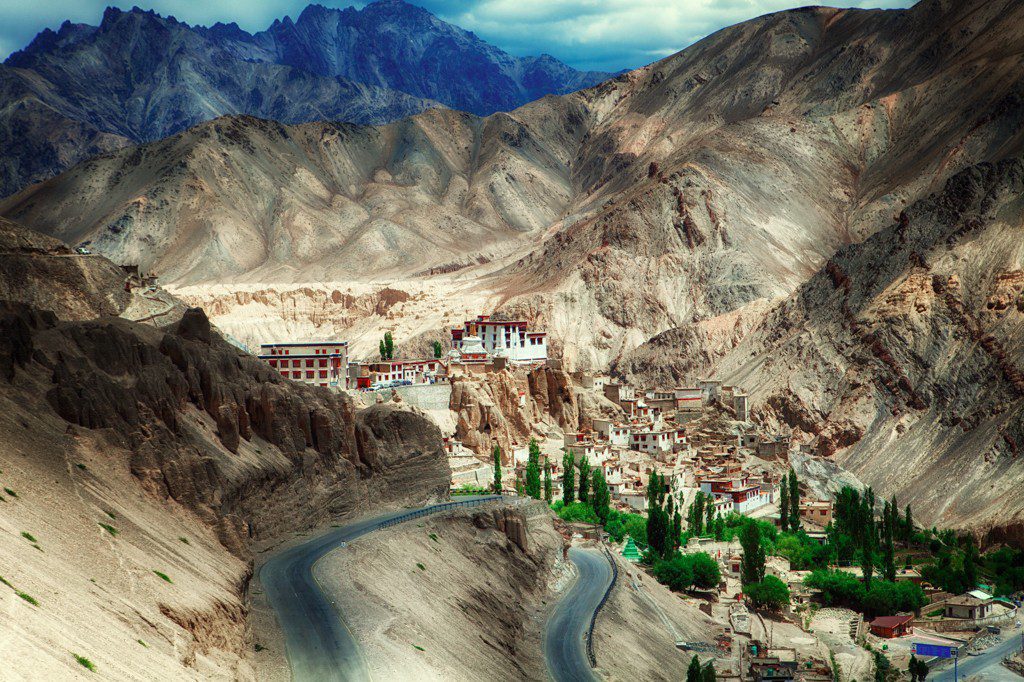

Two months later, I found myself in an entirely different landscape. The ochre sands of Ladakh stretched before me, the wind carrying the low hum of Buddhist chants from a distant monastery. Instead of café-lined streets, there were paths carved into the Himalayas, winding through rugged valleys, past ancient stupas and prayer wheels spinning in the breeze. The air was thin, the mountains sharp against a sapphire sky. If the Camino was a well-worn narrative of pilgrimage, Ladakh was a blank page waiting to be filled.

What does the Camino de Santiago have in common with the high-altitude treks of Ladakh? At first glance, nothing. One is a European pilgrimage, a path of faith and community. The other, a solitary trek through the towering Himalayas, demanding not only physical resilience but also a deep confrontation with silence and space. But in both, there exists a shared truth: walking is more than just movement—it is a meditation, a transformation.

For centuries, pilgrims have followed the Camino, seeking answers, redemption, or perhaps nothing at all—just the road beneath their feet. Ladakh’s trails, too, have been walked for generations, not just by trekkers but by monks, traders, and seekers of something greater than themselves. These paths, whether leading to Santiago de Compostela or through the high passes of the Himalayas, are more than routes—they are rites of passage.

As I ascended a pass in Ladakh, lungs burning in the altitude, I realized that the greatest treks are not measured in miles but in moments of clarity. Whether it’s the vast meseta of Spain or the desolate beauty of Markha Valley, both demand the same thing: surrender to the journey.

And so, I walked on.

The Spiritual Connection: Pilgrimage Beyond Borders

There is an unspoken understanding among those who walk long distances. Whether it’s along the Camino de Santiago or through the high mountain passes of Ladakh, the rhythm of footsteps on ancient paths speaks a language beyond words. A pilgrimage is never just about reaching a destination—it is a conversation between the traveler and the land, a journey inward as much as outward.

The Camino de Santiago is, at its heart, a sacred undertaking. It has been walked for over a thousand years, drawing seekers of faith, adventure, and self-discovery. The scallop shell, a symbol of the pilgrimage, marks the way, guiding thousands through the rolling vineyards of La Rioja, the medieval villages of Castile, and the misty woodlands of Galicia. Churches, some small and humble, others grand and storied, punctuate the path, offering weary pilgrims a place to reflect, pray, or simply rest.

In Ladakh, there are no scallop shells, no waymarkers carved by centuries of European history. Instead, there are prayer flags fluttering in the wind, carrying whispered mantras across the barren ridges. There are whitewashed stupas standing resolute against a backdrop of jagged peaks. Instead of the ornate cathedrals of Spain, there are monasteries perched on cliffs—Thiksey, Hemis, Lamayuru—where maroon-robed monks chant in a cadence as ancient as the Himalayas themselves.

Yet, despite the differences in faith and geography, the essence of both journeys remains strikingly similar. Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago speak of moments of clarity, of shedding the burdens of modern life one step at a time. In Ladakh, too, trekkers experience the stripping away of the unnecessary. With each day in the mountains, distractions fade—the digital world, the noise of obligations, the weight of expectations. What remains is the sound of the wind, the crunch of gravel beneath boots, and a presence that feels almost sacred.

Walking through the high-altitude trails of Ladakh, I felt the same quiet transformation I had encountered on the Camino. There, I had followed the route of countless pilgrims who had walked before me. Here, I was tracing the paths of monks, traders, and nomads who had moved through these landscapes for generations. In both places, walking was an act of devotion—not to any specific deity, but to the journey itself.

In the end, pilgrimage is not about religion, nor even about reaching a particular place. It is about walking with intention, about moving forward even when the path is uncertain. Whether in the Spanish countryside or the windswept passes of the Himalayas, the lesson remains the same: in the act of walking, we find ourselves.

The Physical Challenge: Endurance in Two Worlds

The Camino de Santiago unfolds like a long, deliberate exhale. Though stretching for hundreds of miles, it is not defined by extreme elevation or technical difficulty. Instead, its challenge lies in endurance—the quiet accumulation of days spent walking, the toll of repetition on muscles and mind. The steady rhythm of footsteps, the weight of a pack pressing into shoulders, the slow understanding that the journey is as much about mental resilience as it is about physical strength.

In Ladakh, there is no such gradual easing into the landscape. There is only altitude. At 3,500 meters, Leh, the gateway to the region, is already higher than the highest peaks in much of Europe. From there, the trails climb steeply—past 4,000 meters, past 5,000, each step a reminder that the air is thinner, the body slower, the challenge greater.

On the Camino, the struggle often comes from within—the nagging ache of a blister, the exhaustion that creeps into the legs after a week on the trail. In Ladakh, the mountain itself becomes an opponent. The body rebels against the lack of oxygen, demanding patience. Altitude sickness is an unpredictable visitor, indifferent to experience or preparation. It does not matter if one has walked the Camino a dozen times—here, the rules are different.

Yet, for all their differences, both journeys teach the same lesson: adaptation. The Camino forces a pilgrim to listen to their body, to understand the rhythms of fatigue and rest. In Ladakh, this awareness becomes even more acute. The best trekkers are not the strongest, but the most patient—the ones who take measured steps, who give their bodies time to adjust, who respect the mountain rather than attempt to conquer it.

There is a moment in every long trek when the body and mind align, when the initial strain gives way to a state of effortless movement. On the Camino, it comes after the first week, when the soreness fades and the trail becomes home. In Ladakh, it arrives after acclimatization, when breathing no longer feels like a battle, when each step carries a sense of belonging rather than struggle.

And then, suddenly, walking becomes something else. No longer an effort, but a meditation. No longer a challenge, but a rhythm. Whether in the golden fields of northern Spain or the stark ridges of the Himalayas, the lesson is the same: endurance is not about pushing through—it is about becoming part of the journey.

The Cultural Landscape: From Spanish Villages to Himalayan Monasteries

In every great journey, the land is more than a backdrop—it is a living character, shaping those who walk through it. The Camino de Santiago and Ladakh’s trekking routes are both defined by landscapes not just of nature, but of culture. The trail is lined with echoes of history, with traditions that persist despite the passage of time. Walking through these places is not just an act of movement, but of immersion.

On the Camino, culture unfolds with every step. Small Spanish villages appear on the horizon, their stone houses clustered around ancient churches. Pilgrims pause at local cafés, sipping espresso or sharing a meal of warm bread, olive oil, and red wine. There is a rhythm to life here, dictated by the road—early mornings, long walks, an afternoon rest in a shaded plaza. The trail is not just a path but a thread weaving through centuries of tradition.

Then, there is Ladakh—a landscape where culture does not settle into villages, but clings to mountainsides. Here, whitewashed monasteries perch above deep valleys, their golden-roofed stupas gleaming in the Himalayan sun. Walking through Ladakh’s trails means passing prayer wheels spun by the wind, crossing paths with yak herders leading their caravans, hearing the distant murmur of monks reciting ancient sutras. The presence of faith is as tangible as the altitude.

Yet, despite their differences, these landscapes offer the same gift: connection. On the Camino, it is found in conversations with fellow pilgrims, in shared stories over communal dinners, in the gentle kindness of strangers who offer a place to rest. In Ladakh, it is found in the quiet hospitality of a homestay, in the steaming cup of butter tea offered by a host who speaks little English but communicates everything with a smile. It is found in the way a trekker sits beside a monk on a monastery step, watching the sun dip behind the peaks in silence.

The cultural landscape of a journey is not only in what is seen, but in what is felt. On the Camino, history lingers in the cobblestones, in the scallop-shell markers that guide the way. In Ladakh, it lingers in the mountain winds, in the fluttering prayer flags that carry whispered mantras into the sky. Both places remind us that walking is not just about movement—it is about belonging. To the trail, to the people we meet, to something greater than ourselves.

Perhaps that is why, long after the journey is over, we find ourselves longing to return. Not just to the places we walked, but to the feeling of walking within a world that was never truly foreign, but somehow, always familiar.

The Landscape as a Teacher: Lessons from the Trail

There are trails that demand to be conquered, and there are trails that insist on teaching us something deeper. The Camino de Santiago and the high-altitude routes of Ladakh belong to the latter. These are not journeys measured by speed or achievement but by the wisdom they offer, step by step, to those who walk them.

On the Camino, the lessons come quietly, slipping into the spaces between footsteps. It is a landscape that unfolds gently—golden fields of wheat swaying in the breeze, the slow rise and fall of rolling hills, the cobbled streets of villages that have existed for centuries. The lesson here is one of patience, of endurance without urgency. The terrain does not rush, and neither do those who walk it. The Camino teaches the art of slowing down, of finding meaning in repetition, of understanding that the journey itself is the destination.

In Ladakh, the lessons are sharper, more immediate. The mountains do not whisper; they command. The altitude reminds you, with every breath, that you are a guest in this environment. The landscape is stark, almost lunar, its beauty not soft and welcoming but raw and unyielding. The lesson here is resilience—not in the sense of pushing through pain, but in surrendering to the rhythm of the land. In the thin air of the Himalayas, the only way forward is with humility. You do not conquer the mountains; you walk among them, at their mercy.

Both landscapes teach another, subtler lesson: the importance of silence. On the Camino, there are stretches of trail where the only sound is the crunch of gravel beneath boots, the distant call of a cuckoo bird, the steady inhale and exhale of breath. These moments, stripped of distraction, become spaces for reflection. In Ladakh, silence takes on an even greater depth. Here, the wind moves between canyons like a voice from another world. The vastness of the terrain makes human presence feel small—not in an isolating way, but in a way that reminds us how little we need.

Perhaps this is the greatest lesson both trails offer: the realization that so much of what we carry is unnecessary. On the Camino, pilgrims begin their journey with backpacks full of things they think they need—extra clothes, books, comforts from home. By the end, many have shed the excess, realizing that the lighter they walk, the freer they feel. In Ladakh, the same truth becomes evident not just in what we carry, but in what we hold onto mentally. The mountains strip away distractions, leaving only the essentials: breath, movement, presence.

Walking changes us, not because of the distance covered, but because of the landscapes that shape us along the way. In the Spanish countryside, in the Himalayan heights, the trails remind us of something we often forget—that the most profound journeys are not about where we go, but about how we learn to walk through the world.

Preparing for Ladakh After the Camino: A Practical Guide

There is a certain confidence that comes after walking the Camino de Santiago. A sense that, after weeks of carrying your own pack, of navigating through landscapes and villages, you are ready for any trail. And yet, stepping into Ladakh is an entirely different challenge. The transition from the Camino’s gentle paths to the rugged, high-altitude treks of the Himalayas is not just about endurance—it is about adaptation.

For those who have walked the Camino and are now drawn to the Himalayas, the shift can be both thrilling and humbling. Below are some key adjustments that Camino pilgrims should consider before setting foot in Ladakh.

1. Adapting to High Altitude

Unlike the Camino, which gently meanders through valleys and rolling hills, Ladakh starts at an altitude that can leave even seasoned trekkers breathless. Leh, the gateway to most treks, sits at 3,500 meters (11,500 feet), higher than the highest point of the Camino. Many trails quickly ascend beyond 5,000 meters, where oxygen is scarce, and altitude sickness is a real concern.

How to Prepare:

- Arrive in Leh at least three days before trekking to allow for proper acclimatization.

- Walk slowly and hydrate constantly—dehydration worsens altitude symptoms.

- Train in high-altitude environments if possible or include uphill hikes in your Camino preparation.

- Recognize symptoms of altitude sickness (headache, nausea, dizziness) and descend if needed.

2. Trekking with Minimal Infrastructure

The Camino is structured for walkers, with albergues, cafés, and rest stops along the way. In Ladakh, once you leave Leh, infrastructure fades into the mountains. There are no cafés serving fresh croissants, no village bars offering wine at sunset. Instead, trekkers rely on homestays, campsites, and the generosity of Ladakhi hospitality.

How to Prepare:

- Pack essentials, as resupply points are rare.

- Bring lightweight, high-calorie food to supplement meals.

- Be comfortable with self-sufficiency—trekking in Ladakh requires more preparation than the Camino.

3. Essential Gear Differences

On the Camino, lightweight packing is a golden rule—minimalist gear, trail runners instead of boots, and simple clothing layers. In Ladakh, the extreme climate demands more.

Essential Gear Adjustments:

- Insulated sleeping bag rated for sub-zero temperatures.

- Sturdy, waterproof trekking boots for rocky, high-altitude terrain.

- Thermal layers and windproof jackets to combat sudden temperature drops.

- Trekking poles for steep ascents and descents.

- High-SPF sunscreen and sunglasses for the intense Himalayan sun.

4. Choosing the Right Trek in Ladakh

Not all Ladakh treks are created equal. For Camino pilgrims, the best transition routes offer cultural richness, manageable altitude, and a blend of challenge and reward.

Recommended Treks for Camino Walkers:

- Markha Valley Trek: Ladakh’s most famous trek, passing through remote villages and Buddhist monasteries, with homestay options.

- Sham Valley Trek: A gentle introduction to Ladakh’s trekking, offering a mix of history, culture, and accessible terrain.

- Lamayuru to Alchi Trek: A spiritual journey through ancient monasteries, mirroring the reflective nature of the Camino.

- Hemis to Tsomoriri Trek: A remote, high-altitude challenge for those seeking true solitude and adventure.

5. Mindset Shift: From Social to Solitary Trekking

The Camino is a communal journey. You meet people at every stage—sharing meals, walking together, forming friendships. Ladakh, in contrast, is a trek into solitude. Days pass with only the sound of wind and boots on gravel. The social experience is replaced with a deeper connection to nature, a more personal reflection.

How to Embrace the Change:

- Accept the silence—Ladakh is a place for deep contemplation.

- Find community in small moments—conversations with a Ladakhi host, a shared smile with a fellow trekker.

- Learn to walk alone. In Ladakh, solitude is not loneliness but an invitation to presence.

Final Thoughts

The Camino and Ladakh are worlds apart—one a historic pilgrimage through European landscapes, the other an untamed trek across the Himalayas. And yet, they both offer the same gift: transformation through walking. To those who have completed the Camino and seek a new challenge, Ladakh is not just another trek—it is a continuation of the journey, a path that calls to those who have learned to listen to the road beneath their feet.

A Journey Without an End

The final steps of a long trek always carry a strange weight. On the Camino de Santiago, those last steps lead to the grand plaza of Santiago de Compostela, where the towering cathedral stands as a silent witness to the countless pilgrims who have arrived before. Some weep, overwhelmed by the significance of the journey’s end. Others collapse onto the stones, exhausted but satisfied. And then there are those who simply keep walking, unable to accept that something so profound could ever truly conclude.

In Ladakh, there is no singular destination that marks the end. There is no cathedral, no final checkpoint. The trail simply fades into the mountains, as if to remind those who walk it that the journey is never finished—it only shifts into another form. I remember standing at the crest of a high pass, prayer flags snapping in the wind, and realizing that there was no need for a final destination. The path itself had been enough.

Both the Camino and Ladakh teach us this lesson in their own way. That the act of walking is not just about reaching a place—it is about what we leave behind and what we take with us. On the Camino, we shed burdens: the weight of unnecessary possessions, the mental clutter of the lives we left behind. In Ladakh, the mountains strip away everything but the essential—breath, movement, silence. What remains is a distilled version of ourselves, shaped by the road beneath our feet.

But what happens after the last step? After the pilgrim’s passport is stamped, after the final pass is crossed? That is where the real journey begins. The challenge is not in completing a trek, but in carrying its lessons forward. Can we walk through life with the same mindfulness we found on the trail? Can we navigate the modern world with the same patience we practiced in the mountains? Can we find meaning in the ordinary, just as we did in every step through the landscapes of Spain and the Himalayas?

Perhaps the greatest gift of both the Camino de Santiago and the high roads of Ladakh is this: they remind us that we are always walking. That no journey truly ends. That the road does not disappear—it simply changes shape, leading us somewhere new.

And so, long after the boots are untied and the dust of the trail has settled, we remain pilgrims. Not just on paths carved into stone or earth, but on the unseen roads of our own lives, forever learning how to walk.

Declan P. O’Connor

Declan P. O’Connor is a writer and traveler who explores the intersection of landscapes and the human spirit.

His work captures the poetry of long walks, the solitude of high-altitude treks,

and the stories hidden along the world’s most sacred paths.