A Fruit with a Soul: When Apricots Whisper in the Wind

The moment I stepped off the narrow road into the dusty apricot orchards of Ladakh, I felt something shift inside me. It wasn’t just the altitude—though at 10,000 feet, even breathing is a kind of poetry—it was the way the light danced through the gnarled branches, the way golden fruit swayed in the breeze like small lanterns of hope. Ladakh, with its dramatic cliffs and sun-scorched valleys, is not the kind of place where you expect sweetness. And yet, here, apricots thrive. Not despite the harshness, but because of it.

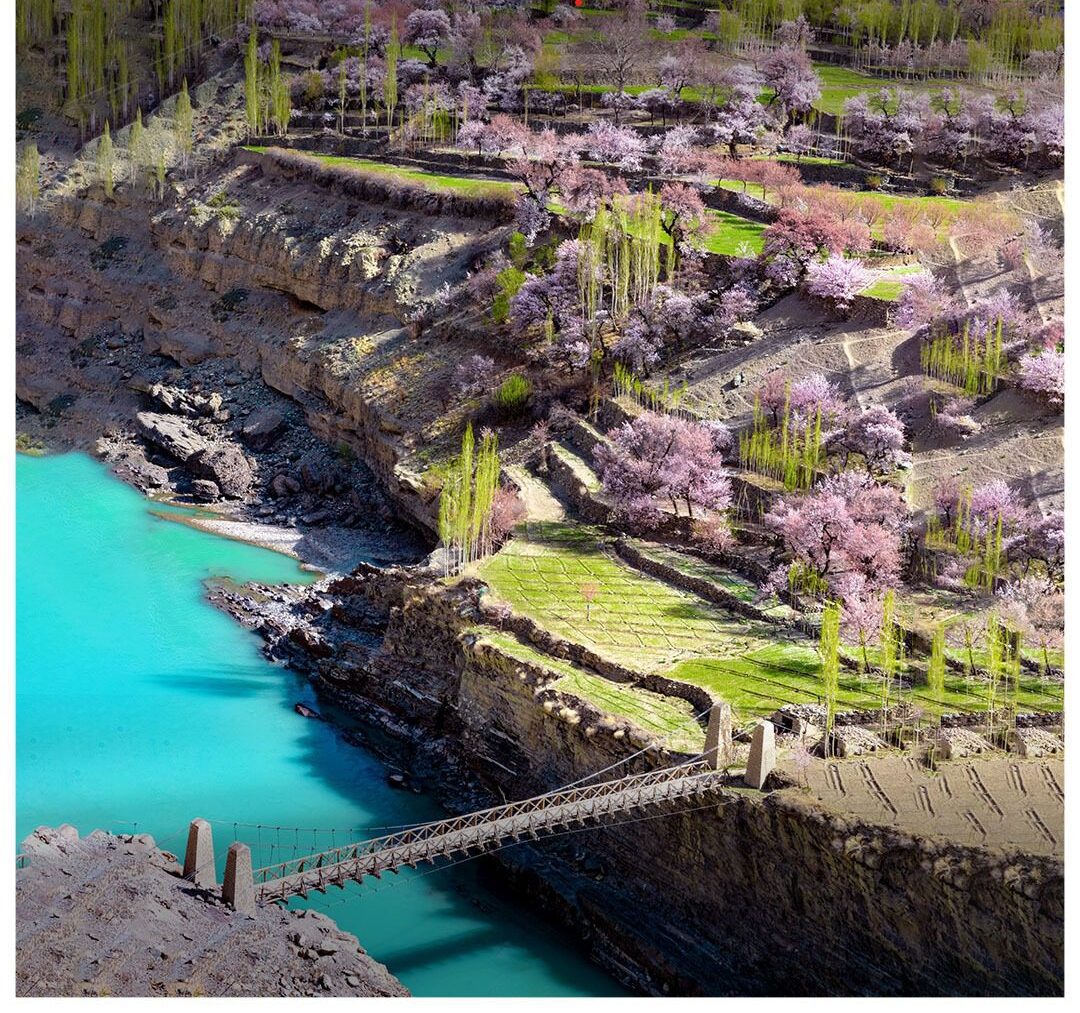

In this high-altitude desert, where winters bite and summers shimmer, the apricot is more than a fruit. It is a quiet miracle. A thread of survival. A flavor of memory. Known locally as “Chuli,” the apricot tree is one of the first to bloom each spring, painting the barren valleys with soft pink and white blossoms. In that brief season, Ladakh transforms. Women gather beneath the trees, laying cloths to catch falling fruit, while children run barefoot among the blossoms, their laughter echoing across the Himalayas.

The apricot has become part of Ladakh’s cultural DNA. Its journey is ancient, perhaps brought by Silk Road traders or whispered into the soil by early Tibetan settlers. In modern times, it remains a lifeline for many Ladakhi families, who rely on it not just for food but for trade, tradition, and identity. The most celebrated variety is the Raktsey Karpo—a sweet, pale apricot found only in this region. It’s rich in nutrients, antioxidants, and stories. Each bite carries the sun, the stone, and the silence of the mountains.

To walk through an orchard in full bloom is to walk through time. You can almost hear the voices of generations—women teaching daughters how to press oil from the kernels, grandfathers cracking stones with their hands, children stringing dried apricots like beads. This isn’t agriculture; it’s alchemy. An ancient knowledge passed down without books or instruction. A way of understanding land not as possession, but as companion.

In Europe, apricots are often seen in patisseries or skincare bottles. Rarely do we think of the root—the land and labor behind them. In Ladakh, they remain fiercely local, proudly unprocessed. A bowl of fresh apricots on a table in Leh is not just a snack; it is a gift, a symbol, a gesture of warmth that transcends language.

This is the soul of the apricot in Ladakh: not just something you taste, but something you carry with you. A reminder that in the most unlikely places, beauty can grow. And in the simplest of fruits, entire worlds are hidden.

A High-Altitude Miracle: Cultivating Gold at 10,000 Feet

There is a certain stillness in Ladakh that humbles you. The wind doesn’t just blow here—it speaks. And if you listen closely, it tells the story of a fruit that shouldn’t exist in this land of stone and silence: the apricot. Against every odd, these golden orbs of sweetness grow in a place where rainfall is rare, winters are unforgiving, and soil is more dust than earth. It is, quite simply, a high-altitude miracle.

Farming apricots in Ladakh is not an agricultural task. It is an act of faith. The trees bloom in early spring, fragile and hopeful, with delicate pink flowers that contrast with the snow still clinging to mountain peaks. The local farmers—often entire families working together—know the rhythm of the land intimately. They prune the branches just after the last snow, whispering to the trees as if they were old friends. They water the roots by hand, drawing from glacial melt or small, ancient canals that snake down from the hills.

This is organic apricot farming in Ladakh at its most elemental—without machines, without chemicals, without haste. Just the earth, the sun, the mountain, and the hands of those who live closest to them. At altitudes above 3,000 meters, these trees are not only survivors; they are storytellers. Their fruit ripens slowly under a thin atmosphere, soaking in sunshine during long summer days and cool, dry nights. The result? Apricots that are unusually sweet, richly flavored, and packed with nutrients.

One of the secrets behind the success of these orchards is the purity of Ladakh’s environment. The air is unpolluted. The water, glacier-fed and mineral-rich. The soil, though sparse, is free from industrial interference. This makes high-altitude fruit cultivation not only viable but, in some ways, ideal. The challenges are immense, but so is the reward. As one farmer told me with a grin, “We don’t grow apricots. We raise them like children.”

Throughout the summer, you’ll find small villages buzzing with quiet activity. Women spread freshly harvested apricots on rooftops to dry in the sun. Children help turn them, one by one, with the tenderness of ritual. Old men sit beneath trees, cracking kernels to extract the oil-rich seeds hidden inside. In this landscape, nothing is wasted. The flesh is dried for winter, the pits are pressed into healing oils, the wood is carved into tools and toys. This is not just sustainable apricot harvesting in Ladakh; it’s symbiosis.

For European visitors used to manicured farms and plastic packaging, witnessing this kind of agriculture can be a revelation. It feels older than time itself. And perhaps it is. Long before organic certification became a global trend, Ladakhis were practicing a kind of farming that respected both the land and its rhythm. Here, nature is not dominated. It is partnered with.

So when you bite into a dried apricot in Ladakh, or run your fingers through a vial of kernel oil, you’re not just experiencing a taste or texture. You’re tasting altitude, listening to wind, and holding in your hands a fruit born from patience, resilience, and an ancient understanding of balance.

Women of the Orchard: Guardians of a Golden Legacy

In the early morning haze of a Ladakhi summer, before the sun has fully cast its gold over the mountains, the orchards come to life with the soft rustle of scarves and the rhythmic steps of women. Their hands, weathered yet graceful, move among the trees with the precision of memory. These women are not just farmers — they are the custodians of an ancient legacy, one woven from fruit, family, and faith.

Ladakh’s apricot orchards are deeply feminine spaces. They are passed down through matrilineal whispers and long afternoons of shared labor. In the heart of villages like Turtuk, Garkone, and Dha-Hanu, the apricot season is a time when women gather, stories are exchanged like seeds, and generations work side by side beneath the canopy of ripening fruit. There is laughter, there is silence, there is the steady hum of continuity.

What outsiders often see as simple agricultural work is, in fact, a sacred cycle. From the blossom to the harvest, it is the women who prune the trees, collect the fallen fruit, dry the slices on rooftops, and press the apricot kernel oil that will soothe chapped lips and tired skin during the harsh winter months. Their knowledge is intimate, inherited not through manuals but through motion — the way a grandmother’s hand guides a young girl’s wrist as she turns each apricot face toward the sun.

This is where apricot skincare traditions in Ladakh are born. With no access to commercial beauty products for much of history, Ladakhi women turned to their land. Apricot oil, rich in vitamin E and antioxidants, is used not only for moisturizing but also for healing wounds, massaging newborns, and softening the sun-weathered hands of farmers. Each vial of this amber-hued elixir tells a story of resilience, of care rooted in terrain, of beauty shaped by earth.

The economic role of these women cannot be overstated. In many villages, the sale of apricot-based beauty products and dried fruits forms the backbone of the household income. Cooperatives are emerging, often led by women, empowering them to export their products beyond the mountains — to Leh, Delhi, even Europe. Yet the work remains humble, slow, and grounded in seasonal rhythms. There are no assembly lines here, no automation. Just time, sun, and hands.

During my time in Ladakh, I spent a week with a family in the village of Sanachay. Each day, I joined Dolma and her daughters as they sorted apricots in the courtyard. We didn’t share a common language, but through gestures and smiles, I learned volumes. How to distinguish the Raktsey Karpo variety by touch. How to store dried fruit in hand-woven sacks. How to crack the pits just right without crushing the seed inside. Their pace was unhurried, meditative. It was work, yes — but it was also a kind of devotion.

These women are the quiet architects of Ladakh’s apricot heritage. Without them, the trees would grow wild, the fruit would fall unnoticed, the stories would wither. Their labor is often invisible to visitors, hidden behind stone walls or curtained verandas. But if you pause, look closer, and listen — really listen — you’ll find their presence in every drop of oil, every bite of dried fruit, every tree that blooms in spring. They are the golden threads that bind past to present, root to blossom.

Blossoms and Blessings: When Apricots Paint the Valley Pink

Spring arrives late in Ladakh, as if hesitating on the edge of the Himalayas. But when it finally steps into the valleys, it does so in silence and in bloom. Apricot trees, bare and lifeless all winter, suddenly erupt in soft pink and white flowers, transforming the austere landscape into something tender and otherworldly. It is fleeting, often lasting no more than ten days—but in those precious moments, time in Ladakh seems to slow down, as if the entire region is holding its breath.

In villages like Garkone, Darchiks, and Takmachik, the arrival of the blossoms is not just a sign of seasonal change; it is a spiritual event. Locals gather under the trees, lighting butter lamps, whispering prayers, and offering their gratitude to the land. The trees are more than trees—they are ancestors, providers, silent witnesses to generations. The air becomes thick with the scent of renewal, and even the most weathered stone houses seem to soften in the presence of such fragile beauty.

As a traveler, arriving during the Apricot Blossom Festival in Ladakh feels like stumbling into a secret kept by the mountains. There are no neon signs or packaged tours. Instead, you’ll find handmade apricot sweets on family tables, schoolchildren performing dances in village courtyards, and old women in traditional woolen robes humming songs passed down through centuries. The celebrations are modest but deeply heartfelt, grounded in the rhythms of the land rather than the pull of tourism.

This is also the season when the connection between people and nature is most visible. Families walk through their orchards each morning, inspecting buds, touching petals, speaking softly to the trees. The blossoms are fragile, vulnerable to sudden winds or a late frost, and so they are treated with reverence. Farmers know that a good bloom can mean abundance in summer; a poor one, hardship. Thus, these delicate flowers carry the weight of an entire season’s hope.

Photographers from Europe often come chasing the perfect image — rows of blooming trees against snow-capped peaks — but what they find is something richer. They find grandparents placing small blossoms behind their grandchildren’s ears. They find women collecting fallen petals to brew into herbal teas. They find stillness, and with it, understanding. The kind of understanding that can’t be rushed, that grows only through observation and quiet presence.

The apricot blossom season in Ladakh is more than beautiful. It is a moment of balance. Between winter and summer, silence and song, stillness and preparation. It reminds us that resilience and softness can live side by side. That even in one of the harshest climates on earth, tenderness finds a way to bloom.

If you are lucky enough to witness this season, you’ll find it lingers long after the petals have fallen. Not just in your camera, but in your breath. In your bones. In the part of you that longs for things delicate and true.

Apricot Alchemy: From Orchard to Skin and Spoon

There’s a kind of quiet magic that begins the moment an apricot falls from a tree in Ladakh. Sun-kissed and plump, it lands softly on the earth, only to be gathered by a gentle hand within hours. What happens next is not industry—it is alchemy. A transformation that has nothing to do with factories or machines, and everything to do with tradition, sunlight, and human touch.

In a courtyard in the village of Saspol, I watched a family prepare apricots for drying. The fruit was halved with care, seeds scooped out and set aside, the flesh placed on woven trays. These trays were then laid out across flat rooftops, where the Ladakhi sun—dry, sharp, and abundant—became the only ingredient needed. There is no rush. The drying process takes days. The apricots gradually deepen in color, from gold to amber, their flavor concentrating into a sweet-tart essence that speaks of altitude and patience.

While the flesh is drying, the pits begin their own journey. Cracked open by hand or with small tools, they reveal the smooth seeds hidden inside—seeds rich in oil, and even richer in cultural meaning. This is the beginning of apricot kernel oil production in Ladakh, a process passed down through generations, especially among women. The oil, pressed cold and slowly, is a treasure: used to moisturize dry skin, soothe muscle aches, and even anoint newborns. In a land where winters can be cruel, this golden oil is as close to a potion as anything I’ve ever seen.

In village kitchens, apricots take on yet another life. They’re cooked down into jams thick with sunshine, folded into traditional breads, or turned into syrups served at weddings and festivals. Some households still follow traditional Ladakhi apricot jam recipes, often adding nothing more than glacier water, raw sugar, and time. There’s something profoundly nourishing in tasting a jam that’s never left the valley it came from.

And then there are the confections—dried apricots stuffed with nuts, dipped in mountain honey, or paired with local cheese. These are the quiet luxuries of Ladakh, far from the reach of export markets but deeply woven into the rhythms of local life. For Ladakhis, the apricot isn’t just a fruit. It’s a pantry, a remedy, a source of beauty. A single tree offers nourishment for body and soul.

The modern world has taken notice. Small cooperatives now package apricot-based skincare products and artisanal jams for sale in Leh’s markets and beyond. European visitors, often drawn first by the landscape, discover these products and bring them home as gifts and memories. But behind each bottle, each jar, there remains a story of slow care. A woman hunched over a sunlit table, a child placing fruit slice by slice onto a tray, a grandmother reciting how her own mother once did the same.

This is the true essence of apricot alchemy in Ladakh: not just the transformation of fruit, but the preservation of wisdom. A fruit becomes a balm, a meal, a story. In a world spinning ever faster, Ladakh reminds us that some of the most powerful changes happen slowly—and always in good company.

Ancient Trade and Timeless Taste: A Hidden Economy

Long before roads were carved into the mountains and tourism found its way to Leh, apricots were already traveling. Packed carefully in cloth sacks, they journeyed across valleys and ridges, crossing into Baltistan, Kashmir, and Tibet. They moved not as luxury goods, but as necessities—portable sunshine in a harsh climate, currency in a place without coins. In this corner of the Himalayas, apricots quietly built an economy.

Unlike bustling trade markets in big cities, Ladakh’s apricot economy has always been hushed and intimate. At its heart are family orchards, often no bigger than a European vegetable patch, where generations have harvested fruit not for wealth, but for balance. Dried apricots were traded for barley or butter, their oil bartered for wool, and the wood of old trees used to craft tools and bowls. Every part of the apricot tree had a role to play—nothing wasted, nothing ornamental.

Even today, this quiet rhythm continues. In villages like Skurbuchan and Khaltse, small cooperatives have emerged, many led by women, producing artisan apricot products in Ladakh that are gaining interest in markets as far as Delhi and Mumbai. These include pressed kernel oil, sun-dried fruit, handmade soaps, and preserves—all prepared using traditional methods that require more time than modern factories would ever allow. Their value lies not in quantity, but in quality, story, and soul.

Visitors often ask why these products aren’t more widely available. The answer lies in Ladakh’s geography—and its values. This is not a land of mass production. There are no conveyor belts, no overnight shipping. Instead, goods move with the seasons, following ancient trade routes that still pulse gently under the modern asphalt. A box of Himalayan dried apricots may take weeks to reach Leh from a remote village. But when it does, it carries with it the essence of altitude, silence, and care.

European travelers discovering these local markets are often surprised by how rich and flavorful the fruit tastes. “It reminds me of my grandmother’s orchard in southern France,” one woman told me in Leh, holding a small bag of Raktsey Karpo apricots as if it were treasure. These are not genetically engineered fruits bred for uniformity. They are shaped by wind, sun, and soil—a taste that can’t be replicated in a lab or on a commercial farm.

This hidden fruit economy in Ladakh is also a form of cultural preservation. With every jar of jam or bottle of oil, traditions are passed down. With every purchase, a village stays connected to its roots. In a global economy that often rewards speed and volume, Ladakh quietly reminds us of another way. One that values lineage over profit, flavor over packaging, and the human hand over the mechanical one.

In the end, it is not just about trade—it is about trust. A tree, tended by the same family for generations. A recipe, unchanged for a century. A traveler, moved not by branding, but by truth. That is the economy of Ladakh’s apricot: timeless, intimate, and quietly profound.

Visiting the Orchards: Slow Travel with Purpose

Some places are not meant to be rushed. Ladakh is one of them. And among its most quietly powerful experiences is walking through an apricot orchard—not as a tourist ticking off destinations, but as a guest of the land. The trees do not perform. They simply exist, as they have for generations, in quiet defiance of rock, wind, and time. To visit these orchards is to step into a slower rhythm—one guided by seasons, stories, and the soft shuffle of footsteps through dust.

Unlike manicured vineyards or curated botanical parks, the apricot orchards of Ladakh remain wonderfully unpolished. In villages like Biama, Sanachay, and Hordas, you’ll find no entrance gates or signage. Instead, you might be invited in by a smile, a wave, or the sight of women laying out apricots on rooftops. It is here, in these seemingly ordinary courtyards, that the extraordinary happens—fruit transformed into food, seeds into oil, moments into memories.

The best way to experience this is through homestays in orchard villages. These offer not just a place to sleep, but an entry into the daily life of Ladakhi families. Mornings begin with sweet apricot tea and views of the mountains bathed in soft light. During the day, you may help sort fruit, turn slices on drying trays, or join a walk to the nearby stream where water is channeled to thirsty roots. Evenings are for long conversations by the hearth, with stories flowing more freely than electricity.

This kind of slow travel in Ladakh is not about spectacle—it is about presence. It is about standing beneath a flowering tree and letting your senses stretch: the scent of sun-warmed bark, the texture of velvet petals, the rustle of leaves stirred by alpine wind. It is about sharing apricot kernel oil with the woman who made it, not from a shelf, but from her hands. It is about recognizing that travel can be a form of listening.

For those interested in sustainable tourism, these orchard visits offer meaningful ways to support local economies. Many families sell handcrafted apricot products directly from their homes—jars of jam, vials of oil, bundles of dried fruit. The money goes straight into the community, helping to preserve both tradition and dignity. And unlike mass-market souvenirs, these items carry a story. A real one. One you can share around your own table back home.

If you’re planning your visit in April, the Apricot Blossom season in Ladakh will offer a visual feast like no other. But even in the dry months of July and August, when the fruit is harvested and processed, the experience remains just as vivid. You won’t find crowds. What you will find is authenticity. Generosity. And a way of life deeply rooted in the earth.

In the end, visiting Ladakh’s apricot orchards isn’t about finding something new. It’s about remembering something old—the value of slowness, the taste of fruit that grew without haste, the joy of being welcomed into someone’s world not as a customer, but as a fellow human being.

Reflections from the Apricot Shade

I remember the moment clearly. It was late afternoon, and the wind had softened. I sat beneath an apricot tree in a village whose name I couldn’t pronounce with confidence, watching the shadows shift across the valley floor. Above me, the leaves whispered stories I could not understand—but I felt them. Felt them in the warmth of the earth, the golden hue of the fruit in my palm, the gentle presence of something older than language. In that quiet, I didn’t need translation. Only stillness.

Ladakh has a way of offering lessons without speaking them aloud. Through its silence, its stone paths, its wind-chiseled monasteries. And through its apricots—those soft, golden fruits that somehow flourish where nothing else dares to. I came here thinking I would write about agriculture. Instead, I wrote about time. About women’s hands, sun-warmed rooftops, and the scent of blossoms carried for miles on mountain air. About the quiet power of something so small, yet so deeply rooted.

From the outside, these orchards may seem simple. A scattering of trees in the shadow of great peaks. But when you stay awhile, you see they are more than that. They are memory-keepers. Healers. Providers. Every dried apricot tucked into a child’s pocket, every vial of oil pressed and passed between women, every tree pruned by hands that have known both abundance and scarcity—these are not acts of economy. They are acts of care.

As a traveler from Europe, you may arrive in Ladakh with a camera, a journal, and a list of things to see. You may leave with something far less tangible but far more lasting: a shift in perspective. A softness in how you walk through the world. An understanding that beauty doesn’t always announce itself—it often waits to be noticed. And sometimes, it grows quietly in an orchard at the end of a dusty path.

The apricot, in its Ladakhi form, is not a fruit to be consumed and forgotten. It is to be respected. To be listened to. To be remembered in winter when the snow falls heavy and the memory of sunlight feels distant. It is, like so much in this part of the world, a symbol of survival made sweet.

And so, I carry it with me. Not just the fruit, but the feeling. The soft hush beneath the branches, the rustle of petals against a child’s sleeve, the deep orange of something ripened by patience. Wherever you are reading this—whether from a Parisian café, a Berlin flat, or a cottage in the Alps—I hope the story of Ladakh’s apricots lingers with you. Gently. Like the taste of something that took a whole season to become itself.

About the Author

Elena Marlowe is a European travel columnist and storyteller with a soul rooted in poetic landscapes and quiet conversations. She seeks places where tradition lingers in the wind, and beauty is found not in spectacle, but in simplicity. With a deep love for the Himalayas and a heart attuned to the rhythm of village life, she writes not to guide, but to accompany.

When not wandering apricot orchards in Ladakh or sipping tea in sunlit courtyards, she resides between southern France and the wild coasts of Galicia—always with a notebook, always listening.