High Places and the Lessons Hidden in Thin Air

By Declan P. O’Connor

Introduction — The Strange Honesty of High Altitude

Why Certain Landscapes Tell the Truth We Avoid

There are journeys you take for the photographs, and journeys you take because something in you has quietly run out of excuses. The Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek belongs firmly in the second category. On the map, it is a ten-day high-altitude route across Ladakh’s Changthang plateau, a sequence of passes, valleys, and lakes that could be described in the efficient language of distance and elevation gain. But in the body, and eventually in the conscience, it unfolds as something else: a long, slow negotiation with the stories you tell yourself about what you can endure, and why you think endurance is always a virtue.

High altitude has a way of stripping conversation down to essentials. Above four thousand meters, the air becomes impolite. It no longer covers for your bad habits. The Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek does not shout its difficulty the way more famous Himalayan routes do; there are no triumphant queues on a summit and no international headlines. Instead, there is a day after day insistence: breathe, step, listen. The landscape, with its vast mineral colors and unhurried horizons, is not interested in your curriculum vitae, your digital footprint, or how well you have optimized your calendar. It is interested only in whether your lungs and your will can keep pace with the slow arithmetic of altitude.

For many European travelers, this part of Ladakh is first encountered on a glowing screen. The images look almost unreal: turquoise lakes, white peaks, ochre valleys, and a scattering of nomad tents that seem arranged by an art director. It is easy to file the Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek under the growing category of “once-in-a-lifetime experiences,” another item on a responsible traveler’s checklist. But the truth is that these high places are not props for self-improvement. They are arenas of honesty where your hidden allegiances—to comfort, to control, to constant stimulation—are quietly exposed.

If you let it, this trek becomes less about conquering distance and more about entering a conversation with a landscape that does not flatter you. It asks why you need to be here, so far from sea level and soft beds, and it refuses to accept the first answer you give.

How Thin Air Reorders What Modern Life Magnifies

Modern life is remarkably efficient at magnifying the wrong things. Your inbox grows, your notifications multiply, your sense of urgency expands to fill every available hour. What shrinks, almost imperceptibly, is your capacity to sit still in your own company. The Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, with its long approach through Leh and Rumtse, begins by reversing those proportions. Before you even set foot on the trail, you are told to acclimatize: to slow down, to rest, to do nothing very productive. High altitude forces a kind of spiritual jet lag in which your body refuses to travel at the speed of your ambitions.

Out on the trail, the air completes the work your to-do list never could. At five thousand meters, you cannot fake presence. Each step between Rumtse and Kyamar, each ascent towards passes like Kyamar La or Mandachalan La, requires attention that might once have been scattered across multiple screens. The mind that once thrived on fragmentation discovers that it has only enough oxygen for one task at a time: lift the foot, place the foot, draw the breath. In this thin air, multitasking dies first.

This reordering is not romantic in the way travel brochures suggest. It can be petty, even humiliating. The person who managed a team, juggled projects, and boasted of resilience may find themselves winded by a modest slope on the Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek. Yet within that humiliation lies the quiet opening for a different measure of a life. What if your worth were not calculated by how much you can cram into a day, but by how gracefully you can do one difficult thing slowly and well?

Thin air has no patience for the illusions that modern life magnifies. But it does make room, if you stay long enough, for a gentler truth: you are smaller than you thought, and more durable than you feared, and you do not need to shout to find your place in the world.

The Geography of Effort — What Trekking Really Measures

The Moral Weight of Elevation Gain

Elevation profiles are usually printed as lines on a graph: clean, abstract, reassuringly flat on a piece of paper. They show you the climb from Rumtse to Kyamar, the long rise over Kyamar La and Shibuk La, the steady undulations towards Rachungkharu and, eventually, the high crossing of Yarlung Nyau La before Tso Moriri. But those lines conceal as much as they reveal. On the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, elevation gain is not just a physical statistic; it is a moral weather report, a record of how you respond when the gradient of your day steepens without asking your permission.

In most of our ordinary lives, effort is negotiable. You can reorder priorities, ask for extensions, choose easier paths. On a long Himalayan trail, effort becomes non-negotiable. The pass will not come down to meet you. The only way forward is upward, and the numbers—five thousand meters, six hours, fifteen kilometers—are simply the terms of the conversation. The question is not whether you can manipulate them, but whether you will meet them honestly. When you pause on a climb and watch your breath leave your body in short, visible bursts, you are watching your pretensions evaporate with it.

This is where the geography of effort begins to intersect with the interior landscape. Each ascent on the Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek becomes a form of confession: how often have you mistaken busyness for courage, or momentum for meaning? The mountains are indifferent examiners. They mark you not on speed, but on whether you keep moving when no one is watching. In that sense, elevation gain measures not just your fitness but your willingness to stay inside a difficult moment without bargaining for an easier one.

To walk these high paths is to accept that some days are simply hard, and that this hardness is not a personal insult but an invitation. Whether you receive it as punishment or as gift may be the most important choice you make above four thousand meters.

How Passes Like Kyamar La and Yarlung Nyau La Shape the Mind

On the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, the passes acquire personalities. Kyamar La is often the first serious test, a reminder that the acclimatization days in Leh and Rumtse were not bureaucratic formalities but acts of respect. Shibuk La introduces the wide, salt-touched presence of Tso Kar below, hinting that water has its own altitude stories to tell. Later, Horlam La feels almost gentle, a reprieve before the more demanding work of Kyamayaru La, Gyamar La, and finally Yarlung Nyau La, the highest threshold between you and the blue mirror of Tso Moriri.

These names, unfamiliar to most European travelers, become landmarks in an inner cartography. Each pass forces a reckoning with your assumptions. At the beginning, you may treat them as obstacles to be conquered: ticked off, photographed, celebrated, shared. By the time you approach Yarlung Nyau La, the posture may have shifted. You begin to sense that the passes are less like opponents and more like stern teachers. They compress time and attention into a few crucial hours in which you cannot pretend to be anyone other than who you are.

The mind, under this pressure, has choices. It can complain—about the steepness, the cold, the thin air, the betrayal of muscles that once seemed reliable. Or it can grow quiet enough to notice what the landscape is actually offering: the way the light changes on distant ridges, the sound of wind combing through dry grass, the small acts of mutual care within a trekking group. The passes shape you by forcing this choice again and again. Will you narrate the experience as an injustice, or as a demanding form of grace?

In a world that trains us to seek the shortest, smoothest route to every objective, there is something subversive about a journey that insists on length and difficulty. The Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek suggests that some truths can only be learned on the long, steep way round.

Nomadic Wisdom — The Changpa and the Unhurried World

Endurance as a Cultural Value, Not a Sport

For many visitors, endurance is a weekend hobby. It is measured in race medals, fitness apps, or the proud soreness after a successful challenge. For the Changpa nomads you encounter near Rachungkharu or along the marshlands beyond Tso Kar, endurance is not an event but a way of being. Their lives are arranged around the slow, demanding requirements of yak and pashmina goats, the movements of weather, and the fragile logic of high-altitude grass. On the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, you cross their world as a temporary guest; they inhabit it as a long argument with the elements that began generations before you arrived.

The difference becomes clear in the small things. A European trekker, wrapped in the latest technical fabrics, may view a sudden snow squall as an emergency. A Changpa herder treats it as a data point in a lifetime of reading the sky. Where the visitor sees hardship, the nomad sees work; where the visitor feels heroic for reaching a campsite at 4,800 meters, the Changpa child treats that altitude as the backdrop of childhood. To walk through this landscape is to realize that what you call “extreme” is simply “home” for someone else.

This realization is quietly destabilizing. It invites you to question the story in which your trek is the central drama and everyone else is a supporting character. On the Rumtse to Tsomoriri route, the Changpa are not extras; they are the primary witnesses to what endurance means when there is no finish line and no applause, only another winter to survive. Their unhurried world reveals endurance as a cultural value: less about personal glory and more about collective continuity, less about pushing limits for their own sake and more about honoring the fragile contract between people, animals, and land.

Once you have seen endurance in this light, it is harder to treat your own effort as a private triumph. You begin to suspect that the higher lesson of this high-altitude trek lies not in how far you can go, but in how humbly you can stand inside someone else’s story.

What the Marshlands of Rachungkharu Whisper About Survival

The word “plateau” suggests flatness, but the Changthang is full of subtle textures. Around Rachungkharu, the landscape softens into marshy pastures where the ground yields slightly underfoot, and streams wind through the grass like veins. This is where the Changpa bring their herds, and where trekkers on the Rumtse to Tso Moriri route often pause for a rest day. At first glance, it looks almost gentle after the stark passes: a place to recover, to drink tea, to watch clouds drift over distant ridges.

But the marshlands are not simple. They are the product of delicate negotiations between snowmelt, soil, temperature, and time. Too much or too little of any element, and the balance fails. In this sense, Rachungkharu is a quiet seminar on survival. The nomads who pitch their tents here are reading the same signs you are, but with a far more detailed vocabulary. They understand which patches of grass will sustain their animals, which shifts in the wind signal trouble, which changes in the water’s behavior hint at deeper climatic unease.

As an outsider, you can only glimpse this knowledge, but even a glimpse is instructive. Survival here is not achieved through domination but through attentiveness. The Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek leads you across a landscape where success is measured not by how thoroughly humans have reshaped their environment, but by how carefully they have learned to listen to it. The marshlands remind you that resilience is not a static quality but an ongoing conversation with forces you do not control.

In an age when much of Europe debates climate policy in conference rooms, standing in these high wetlands adds a different dimension to the discussion. You see, in real time, what it means for a way of life to depend on the thickness of grass and the timing of meltwater. The questions of survival cease to be abstract and become, instead, as immediate as the ground beneath your boots.

The Silence Beyond Effort — Where Endurance Ends and Meaning Begins

Why the Body Breaks Before the Spirit Learns

Anyone who has walked long enough at altitude knows the moment when the body begins to vote against the enterprise. The pack feels heavier, the trail steeper, the hours longer than the map promised. On the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, this mutiny may arrive on a long day of double passes, or in the final climb towards Yarlung Nyau La. Your muscles, which once seemed like reliable allies, start filing complaints. Your lungs negotiate every breath. Fatigue becomes a language of its own.

Yet curiously, this is often the point at which the spirit begins to learn. When comforts fall away, perspective has room to move in. The mind that once busied itself with travel logistics and route comparisons begins to ask more awkward questions: Why do I believe that I must always prove myself? What exactly do I think I am earning with this suffering? High altitude unclutters the stage so that these questions can appear without distraction. The Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek does not answer them for you, but it refuses to let you ignore them.

This is where endurance reveals its limits as a moral category. The body can be driven too far, the will can be misused, and the cult of pushing through can become its own quiet idolatry. The mountains do not applaud such excess. They simply watch, indifferent, as you learn that wisdom sometimes lies in turning back, resting longer, or admitting that this pass will be crossed tomorrow instead of today. The lesson is not that endurance is unimportant, but that it is not ultimate.

In this sense, the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek is less a test than a tutorial. It shows you where the body begins to fray so that the spirit can finally see itself clearly. The breaking point is not a failure; it is a frontier where new meanings can be negotiated.

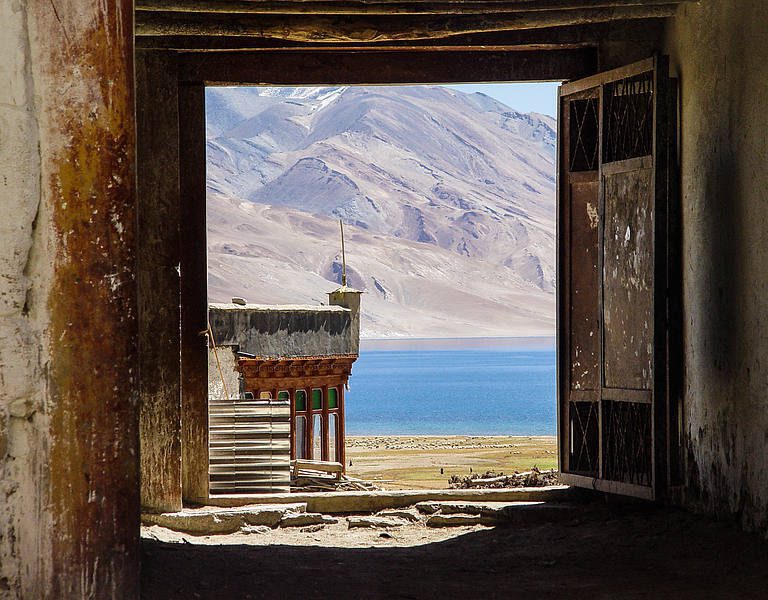

Tso Moriri as a Lesson in Stillness

After days of movement, the first full view of Tso Moriri can feel almost unfair. You have climbed passes, crossed wetlands, watched dust rise from the hooves of yak and horses, and now the world suddenly presents you with a vast, untroubled plane of blue. The lake lies at over 4,500 meters, yet it looks like an argument for rest. Peaks ring it like patient witnesses. Karzok village sits on its northern shore, modest and self-contained, as if to remind you that human life does not need to dominate a landscape to belong in it.

Here, the logic of the trek changes. The Rumtse to Tso Moriri journey, which has so far been defined by motion—Leh to Rumtse, Rumtse to Kyamar, passes and camps and long valley floors—suddenly asks you to stop. The most meaningful way to engage with Tso Moriri is not to circle it as quickly as possible, but to sit beside it and let your racing systems decelerate. The lake is a mirror in more than the literal sense. It reflects back not only mountains and sky, but the kind of traveler you have been so far.

For many visitors, there is a temptation to treat even this stillness as a resource to be consumed: one more sunrise to capture, one more set of drone footage to upload. But the lake resists such extraction. Its scale and silence dwarf your itinerary. In the presence of Tso Moriri, you are invited to reconsider what the whole journey has been about. Was it to prove that you could endure a high-altitude trek, or to rediscover a form of stillness that your everyday life has forgotten how to host?

In that sense, the lake is the final correction to the cult of endurance. It suggests that the highest use of your hard-earned stamina may not be to keep moving, but to finally hold still long enough for gratitude to catch up.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do, after walking so far, is to let a place be bigger than your plans for it.

Questions from the Changthang — FAQ for the Thoughtful Trekker

What Kind of Traveler Really Belongs on the Rumtse to Tso Moriri Trek?

The honest answer is that this high-altitude route does not belong to any single type of traveler. It is demanding enough to deter the casually curious and yet gentle enough, in its long valley stretches, to welcome those who are willing to train and prepare. The people who gain the most from the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek are not necessarily the fittest, but the most teachable. They are the ones who arrive with questions rather than expectations, who understand that the Changthang plateau is not a stage set built for their personal transformation but a living, working landscape into which they are briefly admitted.

For a European audience accustomed to efficient transport and predictable infrastructure, this trek offers a deliberate departure from convenience. It rewards those who can tolerate uncertainty: weather that changes faster than forecasts, paths that feel longer than guidebook estimates, bodies that do not always perform on command. If you are willing to meet these uncertainties with humility instead of irritation, you already belong here more than you think. The trek is not an exam for elite athletes; it is a long conversation with altitude that favors honesty over heroics.

In practical terms, anyone considering the Rumtse to Tsomoriri trek should be comfortable with multi-day hiking, open to basic camp life, and prepared to follow the guidance of local teams who understand these mountains better than any imported device. The deeper requirement, however, is interior: a readiness to let the journey unsettle your habits of control and speed. If you can bring that, the trail will meet you halfway.

Conclusion — What We Bring Back to Sea Level

Frequently Asked Questions from the High Plateau

Certain questions echo across campfires no matter which group has pitched its tents on the plateau. They are usually practical on the surface and existential underneath. Will I manage the altitude? What if I am the slowest in the group? Why does this feel harder than it looked when I planned it from my kitchen table in Paris, Berlin, or Barcelona? The Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek does not answer these questions with neat slogans, but it does supply context that our lowland lives often lack.

Yes, you can prepare for high altitude with careful acclimatization in Leh and Rumtse, with patience on the initial days to Kyamar and Tisaling, with respect for the advice of guides who have read these slopes since childhood. But the deeper question—how to live with your own limitations—will remain open long after your oxygen saturation returns to normal. The real reassurance is not that you will never struggle, but that struggling honestly can be a legitimate way of belonging in a place like this. To feel small, slow, or vulnerable on the Rumtse to Tsomoriri route is not a sign that you do not belong; it is evidence that you are finally encountering the mountains on their own terms.

Another common question concerns meaning: What will I bring back from this trek besides photographs and sore legs? The most durable answers are usually quiet. Perhaps you will bring back a different relationship with time, having learned that ten slow days can be fuller than a month of hurried weekends. Perhaps you will bring back a renewed respect for the unseen labor that supports every journey: the guides who know which clouds matter, the cooks who keep stoves going at four thousand meters, the Changpa families whose grazing patterns shape the very paths you walk. These are not souvenirs in the usual sense, but they travel home with you just the same.

In the end, the plateau leaves you with a question to carry back to sea level: How much of the clarity you found in thin air are you willing to protect once the air is thick again with distraction? The answer, unfortunately, cannot be packed into your backpack. It will have to be lived.

Endurance, Remembered Differently

When people ask you later about the Rumtse to Tso Moriri trek, it will be tempting to emphasize the statistics: the passes you crossed, the maximum altitude you reached, the number of days you went without a hot shower. These details have their place; they are the visible scaffolding of the journey. But if the trek has done its deeper work, the story you eventually tell will sound different. You will speak less about how hard you pushed and more about how quietly you listened—to your own limits, to the wisdom of the people who live here, to the eloquent silence of lakes like Tso Kar and Tso Moriri.

Endurance, remembered in this light, ceases to be a tool of self-promotion. It becomes, instead, a form of stewardship: of your body, of your attention, of your small place in a larger, older world. You may discover that the most valuable thing you gained in those ten days was not proof of your toughness but permission to live more gently with yourself and others. The trail from Rumtse to Tsomoriri does not demand that you return home as a different person overnight. It simply invites you to walk a little more slowly through your own life, to leave more space between stimulus and response, to treat your days less as commodities and more as gifts.

If there is a final lesson in the altitudes that teach what endurance forgets, it is this: you are allowed to stop striving long enough to be changed. The mountains of Ladakh will continue their patient work whether or not you visit them. But if you do, and if you let their thin air strip away a few of your illusions, you may find that the most radical act you can carry back to Europe is a renewed willingness to be present where you already are.

You came to the high plateau to see something extraordinary. You leave with the quieter discovery that ordinary life, lived with a little more humility and a little less haste, can be a summit of its own.