Ten Thresholds, One Ladakh: Villages That Refuse to Be Background

By Sidonie Morel

Before the map becomes a day

Altitude, errands, and the first small rules

In Ladakh, the word “village” is not a decorative stop on the way to somewhere grander. It is where tea is boiled, where barley is beaten into flour, where shoes are left by the door because the floor must stay clean, and where the shape of a day is still made by weather, water, and the distance to the next reliable shop. “10 Villages, One Ladakh: A Journey from Nubra to Zanskar and Kargil” sounds, on paper, like a neat route. On the road, it is a sequence of thresholds: gate-latches, courtyard steps, low ceilings, prayer stones, hand-pumps, steel kettles, solar panels angled toward thin sunlight.

If you arrive from Europe, the first adjustment is not philosophical. It is physical and practical: altitude asks you to do less, then do it slowly. In Leh, you learn the quiet rhythm that makes the rest possible—short walks, warm drinks, early nights, and a reluctance to sprint up stairs for no reason. Hydration is not an internet tip here; it is visible in how people carry bottles and how guesthouses keep thermoses of boiled water near the kitchen. The air is dry enough to chap lips in an hour. The light has a hard edge at midday. In winter, it is the stove that dictates the evening; in summer, it is the sun and the wind.

The second adjustment is social: villages are not museums. They are working places with fields, animals, and schedules. A respectful stay is mostly made of ordinary acts—asking before photographing people, keeping your shoes off when the host does, accepting that a family’s sitting room is not a lobby. The practical matters (permits, road closures, fuel) still exist, but they belong inside the story of each day: the pause at a checkpoint, the stop for tea when someone says the pass is rough, the moment you discover that cash matters again because there is no signal and no card machine will ever appear.

Nubra: orchards, riverbeds, and sand that should not be there

Turtuk, where apricots and borders share the same air

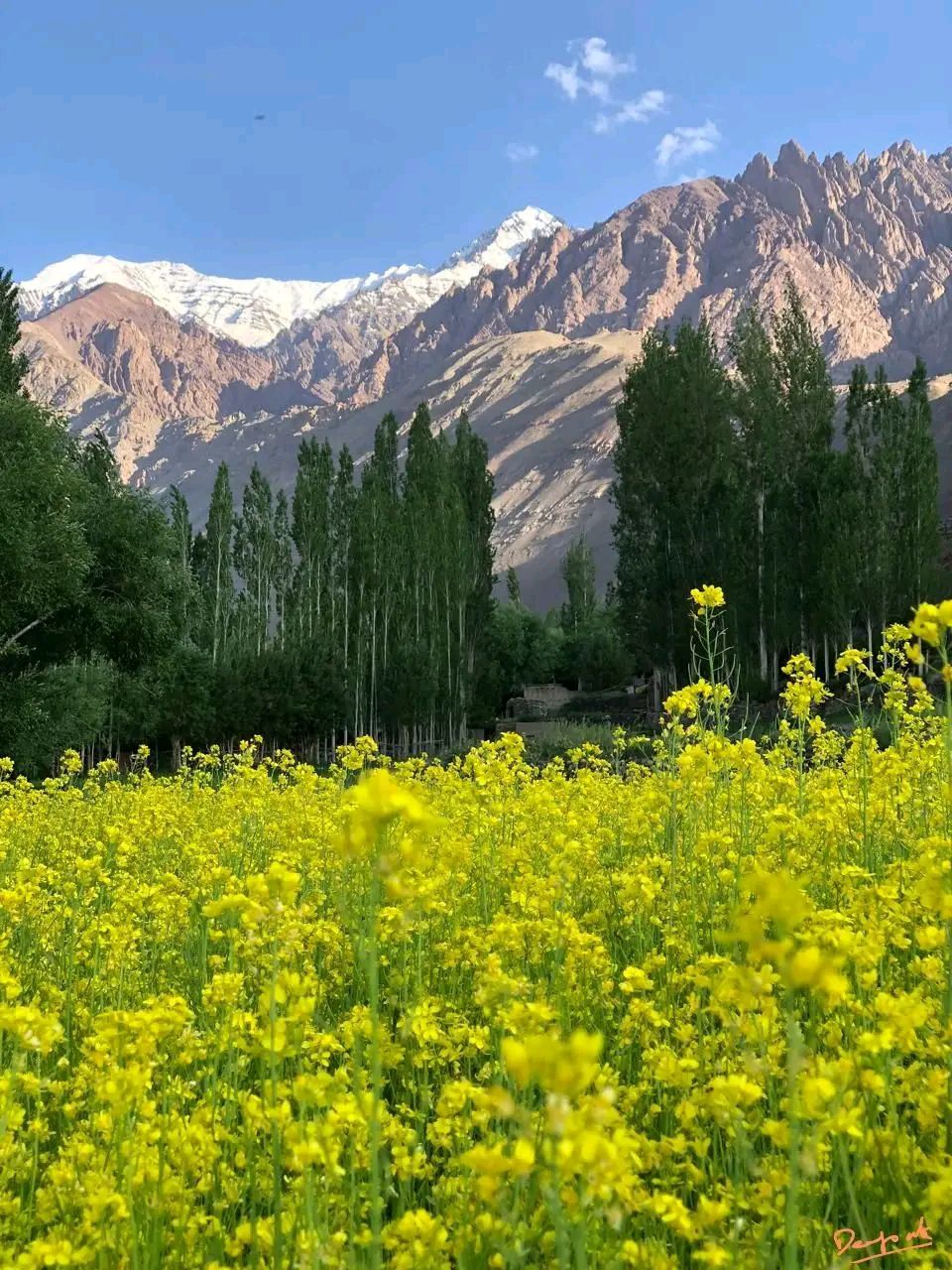

The road into Nubra loosens the body with its gradual unfolding: the high drama of Khardung La (or the newer tunnels and alternate lines that change year by year) gives way to a valley that suddenly contains trees. You notice green in the same way you notice water after a long dry walk—first as a hint, then as a certainty. Turtuk sits at the northern edge of this world, closer to the border than most visitors need to remember, and yet it is the domestic details that stay with you: apricot trees bending over stone walls, narrow lanes where sunlight arrives in strips, and small bridges that carry you over irrigation channels with a mild, persistent murmur.

In summer, fruit is not a metaphor; it is a task. Apricots are collected, sorted, split, and laid out to dry. In the morning, you can watch hands move with practiced speed—fingers that have learned the exact pressure needed to separate pit from flesh without waste. The air can smell faintly sweet near the drying racks, while the rest of the village holds that dry, mineral scent common to high desert places: dust, stone, wood warmed by sun. Even if you arrive with a camera, it is worth arriving first with patience: sit, drink tea, let the day’s noise settle. The village has its own pace; the most honest moments are usually ordinary ones—someone carrying fodder, a child balancing a water container, a grandmother adjusting a shawl and stepping back into shade.

Turtuk is often described with labels—culture, history, borderland—but the texture is simple: gardens behind walls, courtyards with stacked firewood, bread on a plate, and the thin metallic sound of a spoon against a glass. In a place that feels remote on a map, the intimacy of household life is what makes it legible.

Hunder at dusk: dunes, poplars, and the last quiet hour

Hunder is known for sand dunes and Bactrian camels, and the dunes are indeed there—soft ridges of sand set against mountains that still hold snow. The contradiction is not staged; it is a landscape produced by wind and river over time. What is easy to miss is how quickly Hunder changes with the hour. Midday can feel busy: engines, loud voices, the urge to “do” the dunes. Late afternoon changes the proportions. Poplar trees become dark vertical strokes. The dunes take on sharper edges. Footprints appear and vanish as the wind moves sand grain by grain.

If you go to the dunes, go late, and go on foot. Walk far enough that you can hear the river again, faint but present, and far enough that the last cluster of visitors becomes a small knot behind you. The sand under the sole has a specific resistance; it gives and then holds. Your socks will fill with grit. The air cools quickly once the sun drops behind the ridges. These are small inconveniences that clarify the place: this is not a set. It is a living valley where people work, and where tourism arrives as a seasonal layer on top of older rhythms.

Hunder’s village lanes, away from the dunes, are where the day returns to its true scale: gardens, low walls, dogs dozing in dust, an old bicycle leaning against a gate. If you stay in a homestay, the evening is often a practical exchange—dinner served early, hot water offered in a bucket, advice about the road ahead. The warmth is not a performance; it is a habit shaped by geography. In Nubra, the night arrives quickly and without warning. That is when the stove and the kitchen become the center again.

Aryan Valley: courtyards close to the road

Hanu and the choreography of work

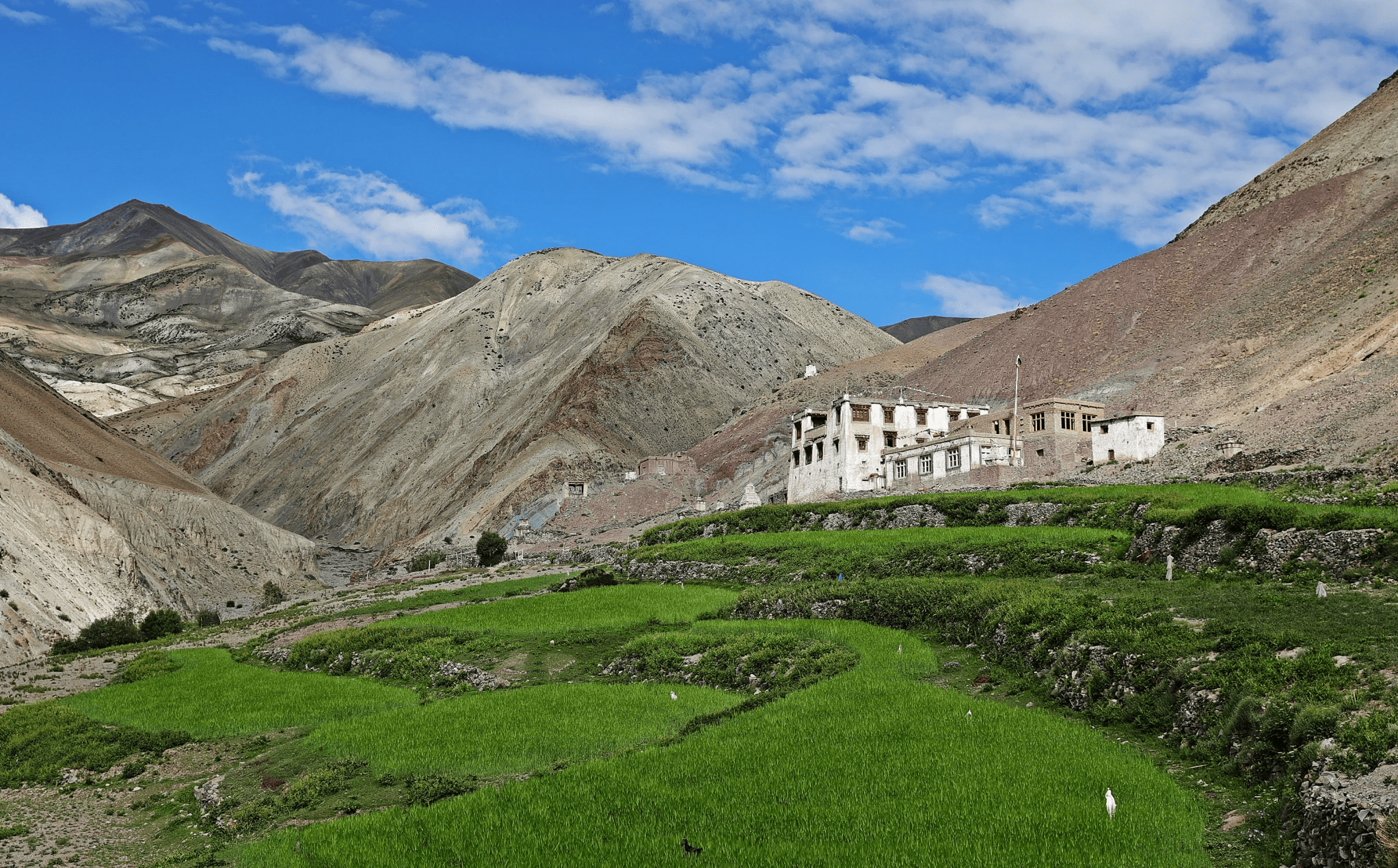

From Nubra, the movement west and south shifts the scenery and the density of settlement. Aryan Valley—often spoken of in ways that flatten it—becomes clearer when you stop speaking and start noticing the layout of labor. In Hanu, fields are not distant; they sit almost inside the village. Paths between houses feel like extensions of courtyards. Water is guided into narrow channels with the kind of seriousness that comes from living in a dry place: nothing is wasted, nothing is assumed.

What you will see depends on season. In warmer months, there is a constant movement between field and home: bundles carried, weeds pulled, tools set down and picked up again. In quieter months, you notice the structure—the storage, the wood piles, the way a house is arranged to keep warmth. The details are modest but precise: a woven basket, a flat stone where grain is worked, a cloth hung to dry. Even the soundscape is different from the bigger hubs: fewer engines, more footfalls, more animal bells, occasional voices that carry through the lanes.

Travelers sometimes arrive here with a desire to “understand” quickly. Hanu resists that. It is better approached with ordinary courtesy: greet people, ask before entering spaces, accept that some moments are not for you. If you stay overnight, the real intimacy is not in conversation but in the simple sequence of dinner, washing, and sleep: a kettle on the stove, plates stacked carefully, tea refilled without ceremony, the quiet that follows when the day’s work is done.

Staying lightly in villages that are not staged

In smaller Ladakhi villages, the line between private and public is often more visible than it is in cities: a gate, a threshold, a low wall. Respect is therefore visible too. Keep your voice down in narrow lanes. Avoid walking through fields unless you are clearly invited. Ask before photographing people, and accept “no” with ease. When visiting in groups, the impact is immediate: a courtyard that comfortably holds two guests can feel crowded with six.

Practicalities can be folded into this same ethic. Carry enough cash for homestays and small purchases; do not assume digital payments. Bring a water bottle and refill where your host indicates safe water. Use layers rather than chasing “perfect” warmth—temperatures swing, and houses are heated in local ways that do not always match hotel expectations. These are small preparations that prevent the clumsy behavior of someone who arrives unready and then demands the village rearrange itself.

Lower Ladakh: murals, shade, and the village lane as a timeline

Alchi: quiet courtyards and old paint that still holds light

Alchi is often visited as a monastery stop, and it can be that, but the village context matters. The first noticeable change here is altitude: the air feels slightly thicker, the day slightly gentler on the body. Trees gather around the settlement. Shade becomes a real architecture. In the lanes, you can walk without squinting constantly. The sound of water—channels feeding fields—returns as a regular feature rather than an occasional surprise.

Inside the old structures, the murals are not simply “beautiful.” They are worked surfaces: pigment that has endured smoke, cold, and centuries of weather. The paint holds light in a particular way, absorbing it rather than reflecting it. Standing close, you see texture, not just image—tiny irregularities where brush met wall. If you visit at a quiet hour, you can hear small sounds that are usually drowned out elsewhere: the shift of a caretaker’s steps, the fabric of someone’s sleeve, the soft click of a door latch.

In the village, ordinary life continues beside this old art. People move between fields and homes. A shop might sell biscuits, tea, a few essentials. Someone will be repairing something—wood, a bicycle, a roof edge. This proximity is what makes Alchi memorable: the sacred is not isolated; it sits inside the same daily world of cooking and labor. For a traveler, it is also a relief. After days of high altitude and long drives, the smaller scale lets you see more because you are not always bracing yourself against the environment.

Lamayuru: wind, stone, and a landscape that edits your language

Lamayuru is approached through a terrain that strips away softness. The ground looks granular, as if it has been poured rather than grown. The “moonland” comparisons come easily, but the more useful observation is simpler: the earth here does not pretend to be fertile. The colors are muted—beige, slate, pale brown—with sudden cuts where erosion exposes layers. When wind picks up, it carries dust with a fine insistence. You feel it on your teeth and in the corners of your eyes.

The monastery above the village sits with the confidence of something that has faced weather for a long time. Prayer flags move in a wind that rarely stops for politeness. The sound of fabric snapping can be as present as any chant. Even if you do not linger long, it is worth spending a moment watching how people move here: measured steps on uneven ground, a hand placed on stone for balance, a pause to let a gust pass. The landscape instructs behavior.

Lamayuru also teaches a practical truth about traveling in Ladakh: stops that look simple on a map can feel large in the body. Road conditions vary. Weather shifts quickly. A pass that was clear in the morning may become slow by afternoon. Tea breaks are not decorative; they are resets. In the villages along the highway, you will often see travelers and locals share the same plain foods—noodles, bread, sweet tea—because what matters is warmth, salt, and time to sit.

Hemis country: waiting as a local skill

Rumbak: homestay heat, quiet walls, and the ethics of looking

Rumbak sits in a landscape where “wildlife tourism” is not an abstract category but something that changes how households earn money through winter. The walk in—depending on your approach and the season—introduces the valley’s geometry: narrow paths, slopes that force careful footing, stone walls built with patience. If you come in cold months, you feel the practical austerity immediately: the sun is bright but does not warm everything, shade is sharp, and the wind can make your fingers stiff within minutes.

Homestays are the anchor. The house has a small interior logic that becomes familiar fast: the kitchen is heat, the sitting room is where guests and family gather, and the stove is fed steadily. You notice the texture of fuel—dried dung cakes stacked, wood arranged, ash removed in the morning. Tea arrives again and again, not as a luxury but as a method: warm liquid to keep the body functional, sugar to hold energy, salt to replace what dryness takes. If you carry binoculars and a lens, you also carry time. The day is made of waiting in a cold place while scanning slopes that look empty until they do not.

Snow leopards, when they appear in this part of Ladakh, are often seen at distance. Most of the time, you are looking at tracks, listening to local knowledge, or noticing how livestock moves in response to predators. That is where ethics becomes concrete. There is a difference between watching and pressuring. Respect is not a speech; it is distance kept, noise reduced, and an acceptance that no sighting is guaranteed. In villages like Rumbak, responsible tourism supports households, but it also risks turning the valley into a stage. The best visitors are the ones who understand that the valley does not owe them a performance.

How to carry practicalities without flattening the place

If you intend to visit Rumbak or similar villages near Hemis National Park, prepare for cold nights and basic facilities even when you stay in a warm home. Bring a headlamp. Bring extra batteries that do not fail in low temperatures. Bring a power bank, but expect limited charging. Accept that toilets may be outside and that water for washing may be brought in a bucket. These details are not complaints; they are part of the landscape’s truth.

In winter, roads to trailheads can be unpredictable. In shoulder seasons, snowfall can arrive early. In all seasons, the most useful habit is flexibility: start early, keep your schedule loose enough to allow weather and local advice to lead, and avoid stacking long drives back-to-back at high altitude. European travelers often underestimate how tiring the combination of thin air and rough road can be. In villages, that fatigue shows up as impatience. Plan so you can remain courteous.

Changthang and the high lakes: dark sky, wide water, and small rooms

Hanle: a night that belongs to the village

Hanle is now spoken of as a place for stargazing, and that is accurate, but it is not the full story. The village is a working settlement in a high, open landscape where wind is constant and vegetation is sparse. The road in can be long and exposed. By the time you arrive, you will have noticed how distances behave differently here: what looks close can take an hour, and what looks flat is often gently climbing without showing it.

At night, the lack of glare is not a “feature.” It is a condition of life. Houses do not blaze with decorative lighting. If you step outside after dinner, you notice how quickly your eyes adjust. Stars appear with a density that changes your sense of scale. You also notice human traces: a faint lamp near a doorway, the soft sound of a generator somewhere, dogs moving in the dark. If there is an observatory nearby, it exists alongside village life, not above it. The sky may bring visitors, but the village still wakes to chores, animals, and weather.

To experience Hanle well, stay at least one full night and one morning. Do not arrive late, take photographs of the sky, and leave at dawn as if the village were only a backdrop. Walk slowly in daylight. Observe the dry grass, the stone walls, the pattern of buildings that turn their backs to wind. In the morning, the air can be so cold it feels clean enough to cut, and the light arrives without softness. These are observable facts that explain why the night here matters: it is earned by the day’s severity.

Korzok: the edge of Tso Moriri, where cold arrives early

Korzok sits by Tso Moriri with a directness that can surprise first-time visitors: water that looks vast and still, and behind it mountains with thin snow lines depending on season. The village itself is small but active in the months when roads are open. Homestays and guesthouses operate with a simplicity shaped by altitude. The cold is not dramatic; it is persistent. Evenings can drop quickly, and the inside of a room becomes a negotiated space—blankets, stove heat, the placement of a cup so it does not cool too fast.

Walking along the lakeshore is often the obvious activity, but the village offers a quieter education. Watch how people dress for wind. Notice how supplies arrive and how carefully they are used. In places like Korzok, waste is visible because it does not disappear into a municipal system. Responsible travel means carrying your trash back, refusing unnecessary packaging when you can, and choosing stays that are locally run rather than imported as a temporary luxury.

Birdlife can be a reason to come—depending on season, you may see species that treat this high water as a necessary stop. But even then, the most telling scene can be domestic: a kettle steaming, boots drying near a wall, a host’s hand adjusting a stove vent. The lake is vast. The room is small. The contrast is the village’s daily reality.

Zanskar and Kargil side: stone memory and border wind

Zangla: ruins that still function as a village landmark

Zanskar is often described through the effort it requires to reach it. Roads have improved and routes shift as infrastructure changes, but the valley still holds a sense of distance that is not only measured in kilometers. The approach tends to be long, and you feel the weight of travel in the body: dust on clothes, stiffness in shoulders, the need to stop and drink water even when you do not feel thirsty. Zangla, once a royal seat in local memory, sits with a mix of dignity and wear: structures that have been weathered, repaired, visited, and left again.

Walking toward the old palace area (and the surrounding village) is not a museum route. It is uneven ground, stone steps, and views that expose the valley’s scale. Ruins here are not an aesthetic accessory; they are a reminder that settlements are not permanent in their forms, even when they remain permanent in their place. You may see children playing nearby, animals moved along a path, someone carrying a load across a slope. The past is present in material condition, not in narration.

In Zanskar villages, hospitality can feel particularly matter-of-fact. Tea is offered because it is the correct thing to do. A guest is a guest, not a performance. If you stay overnight, you may see how quickly evening arrives in a valley where the sun drops behind ridges early. The inside of a home becomes an intimate geography: low seating, warm corners, storage arranged for winter. The more remote the place, the more each object looks used for a reason.

Hunderman: a village where remembrance has rooms

On the Kargil side, the landscape carries a different kind of story pressure. Border regions attract narratives. Hunderman—often spoken of as a “ghost village” or a “museum village”—is more precise when described simply: it is a place where war and division have left material traces, and where a community has chosen to hold some of those traces in a small museum-like space rather than letting them scatter into silence.

Walking through Hunderman, you see how memory can be curated without becoming spectacle. Objects are placed with care. Photographs and remnants are arranged to explain rather than to shock. The village itself remains a living settlement; people still inhabit the present while acknowledging a past that is unusually close. The tone is restrained. Visitors are expected to behave with restraint too.

This is where a European traveler may need to adjust expectations again. Not every village exists to comfort you. Some places ask for quietness and a slow pace because the subject matter is heavy. The practical behavior is clear: ask permission, keep voices low, avoid performing sympathy, and do not treat the village as a dramatic backdrop for social media. If you leave Hunderman with anything, let it be simple awareness: borders are not only lines on maps; they shape roads, livelihoods, and the way a village decides what to keep visible.

Ten villages, one Ladakh—held together by ordinary objects

Across this route, what repeats is not scenery but the small domestic economy of survival and care. A kettle appears in every region, even when the tea changes. Blankets are folded and unfolded with a practiced hand. Shoes line up by the door. Water is carried, stored, and treated as a serious matter. The same wind that snaps prayer flags in Lamayuru moves dust across Nubra dunes. The same dryness that cracks lips in Leh makes fruit drying possible in Turtuk. The same cold that makes a night in Korzok feel sharp gives Hanle its clean darkness.

“10 Villages, One Ladakh: A Journey from Nubra to Zanskar and Kargil” is therefore less a checklist than a series of stays. The villages are not interchangeable. They do not offer the same comfort, the same language, the same temperature, or the same relationship to visitors. What they share is the clarity of living in a high desert where resources are limited and weather is decisive. If you travel with time—if you let tea breaks remain tea breaks, if you choose homestays that keep money local, if you carry your trash out—then each threshold you cross becomes less of an entry into “somewhere exotic” and more of an encounter with a place that is quietly busy being itself.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.