A Roadside Valley That Refuses to Be a Label

By Sidonie Morel

Dha Before the Story

The first bend above the river

Approaching Dah and Hanu from Leh, the road keeps close to the Indus and then begins to hesitate—turning, narrowing, lifting slightly above the water. The river is not the kind you glance at once and forget. It presses air into motion. It brings a cooler edge to the dust. It sets poplars and willows in a steady conversation that you can hear even through a vehicle window.

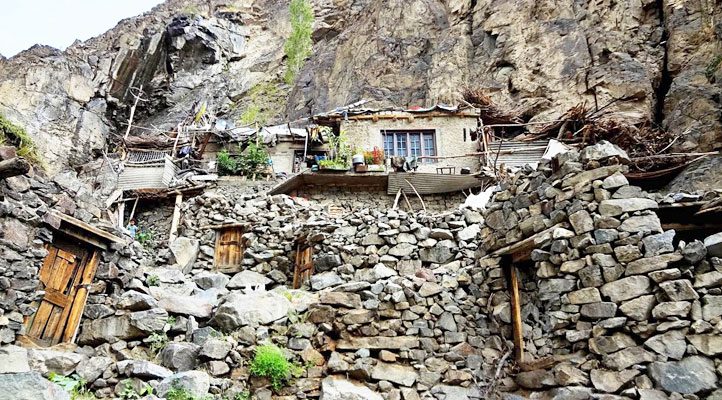

The villages themselves are not announced with ceremony. A few houses gather on the slope. A small bridge appears where a side stream meets the main valley. Terraces take shape—stone-lined steps of cultivated earth that can look, at first, like a patient kind of masonry. When you stop, the practical details arrive: the grit of the road under your shoes, the smell of warmed stone, the faint sweetness of dried fruit from a storeroom, and the clean, mineral note of river water carried on wind.

This part of Ladakh is often approached through a single headline, the sort of word that travels faster than any careful description. It is better to begin with what is visible: orchards and fields, shade trees placed like tools, walls repaired in increments, and the ordinary movement of people who live here year-round.

A village that does not perform

In Dah–Hanu, daily life does not arrange itself for visitors. The working hours are not staged. A woman carries fodder in a bundle so compact it looks almost engineered; the rope bites into her palm. Two boys move in and out of a courtyard with the quick, rehearsed steps of children who have been sent for something twice already. A man kneels beside an irrigation channel and clears it with the end of a stick, redirecting water by a few fingers’ width—a correction that will matter later.

Even the most noticeable details—ornaments, flowered headpieces, bright textiles—are woven into routine rather than separated as spectacle. Clothing is adapted to weather and work; adornment sits beside function, not above it. You can watch someone adjust a scarf not for elegance but for sun and dust, the fabric pulled to cover the mouth for a moment when the road gusts.

Visitors arrive with cameras and questions, but the villages keep their own tempo. That is one reason the primary keyword of this piece—Beyond the Label: Seasons Along the Indus in Dah–Hanu—matters as a promise of method. If you want to understand a place, you have to keep showing up in more than one month, and you have to accept that what you see will often be ordinary.

The Problem With the Word “Last”

How a convenient phrase outruns the valley

There are places that the outside world insists on describing as “the last” of something—last pure, last untouched, last authentic. The word makes a neat postcard and an even neater social-media caption. It also does something quietly damaging: it turns living communities into endings.

In the Dah–Hanu region, that pressure is felt in small ways. It shows up in how visitors ask about origins as if ancestry were a ticket. It appears when someone tries to photograph a face at close range without greeting first, as if the camera were an entitlement. It can even appear in the way “tradition” is demanded on cue, as if a village were a showroom with opening hours.

But this is a borderland with a modern life. Roads are improved and then damaged again by weather. Mobile signals appear and disappear depending on where you stand. Administrative rules change, and people adapt, as they always have. Nothing here is frozen. The most accurate thing you can say about Dah and Hanu is that they continue.

Looking without taking

Respect in a place like this is rarely theatrical. It is a matter of distance and timing. If you want to take a photograph, you ask. If the answer is no, you accept it without negotiation. You do not step into courtyards as if they were public squares. You do not point a lens into a kitchen doorway where someone is working, because the doorway is not an exhibit frame. You learn to wait until people finish what they are doing, and you learn to greet before you observe.

Practicalities matter, too. Dah and Hanu sit along a route that can involve restricted zones and permits depending on current regulations. For European travellers, the simplest approach is to treat permissions and checkpoints as part of the landscape rather than an inconvenience: carry what is required, expect verification without drama, and avoid improvising detours just for the thrill of saying you did. The valley is not improved by a visitor’s bravado.

There is also the question of language. The Brokpa communities in this region have their own linguistic and cultural textures—details that do not compress neatly into a single imported term. If you keep your attention on what is present—speech, work, weather, fields—you will naturally move away from the urge to label.

Seasons Along the Indus

Spring: blossom as a schedule, not a decoration

Spring in Dah–Hanu is often described as if it were a single burst of colour, but what stands out when you return is how organised the season is. Blossom is not merely pretty; it is a working signal. A tree flowering tells you what will need pruning, what will need water, what will need protection from sudden cold. On a morning when the air is still sharp, the blossoms can look delicate and unbothered, but the ground beneath them is busy with footsteps.

Paths between terraces become clearer as snow retreats to higher folds of the valley. Irrigation channels begin to carry more insistently. The first weeds appear where water leaks. In courtyards, tools come out of storage—wood handled smooth by years, metal dulled from use. You see people checking what winter has done: a cracked wall, a gate hinge that needs oil, a roof edge that must be secured before the next wind.

In spring, visitors often arrive for the blossoms and leave with a handful of photographs. If you stay longer, you begin to notice how quickly the valley shifts from bloom to labour. The season is not sentimental; it is transitional and precise.

Summer and autumn: water lines, harvest weight, smoke in the evening

By summer, the valley has a firmer heat. The road dust turns paler. The river’s presence feels more like contrast: water moving below, dry air above. In the fields, you see how carefully water is managed. Channels are not picturesque; they are negotiated, maintained, defended against clogging. A small collapse in a bank can change who receives water first. A blocked channel can cost a crop.

Autumn brings a different kind of inventory. Apricots deepen in colour and then leave the tree. Drying trays appear—flat surfaces set up to catch sun and airflow, the fruit arranged with care rather than speed. The smell of sweetness is not abstract; it is sticky on fingertips, carried on clothing, mixed with the sharper scent of smoke from evening fires. People move heavier loads: sacks, bundles of fodder, containers filled and sealed for winter. Even the sound of the village changes as doors and gates are used more frequently, storage rooms opened and closed with purpose.

For travellers, the most useful understanding of the season is straightforward: roads can be at their best and also deceptive. A clear day can turn quickly. A minor landslide can delay a plan. The valley does not guarantee smooth travel because travel is not its main function.

Winter: storage, silence, and the economy of warmth

Winter is the season most often left out of glossy descriptions. Yet it is precisely in winter that the logic of the villages becomes clearest. Stored grain and dried fruit stop being quaint details and become the backbone of a household. Wool is not a souvenir but insulation. Fires are managed, not indulged. A kettle is used and reused. Water is carried with more awareness of weight and temperature; ice changes the path you choose with your feet.

The valley’s colours tighten: stone, wood, muted fabric. Sound becomes sharper. A dog’s bark travels further. The scrape of a shovel against packed ground has a dry, blunt note. If you are fortunate enough to visit in winter with local guidance and proper preparation, you understand why the word “seasons” belongs in any honest account of Dah–Hanu. The villages are not a springtime set. They are year-round realities.

Inside the Village, Beyond the Slogan

Adornment that belongs to a person, not to a story

Visitors notice adornment quickly: headpieces, flowers, jewellery that catches light. The temptation is to treat these as “traditional costume,” a phrase that can flatten a living practice into a category. What you see, when you pay attention, is more personal. A choice of colour, the way a scarf is tied, the mixture of metal and fabric, and the way someone adjusts an ornament with the same absent-minded competence another person might use to fix a button.

Close observation also makes the tourist myth feel clumsy. A community’s clothing does not exist to prove a theory about origins. It exists because people live here. They have preferences, budgets, practical needs, aesthetic sensibilities, and days when they are dressed for work rather than for anyone’s camera.

It is in these small, specific moments that the article’s central movement—Beyond the Label: Seasons Along the Indus in Dah–Hanu—stops being a phrase and becomes an ethic. The label falls away not through argument, but through attention to a person’s ordinary decisions.

Homes: thresholds, courtyards, and what is not offered for display

To understand a village, watch its thresholds. In Dah and Hanu, a doorway is not simply an entrance; it is a boundary between public and private, between the road and the household’s working life. Shoes are placed with care. A broom leans where it can be reached quickly. A low wall keeps animals from wandering in. Courtyards function as kitchens, workshops, storage, and meeting places depending on the hour.

In a homestay, the practical side of hosting becomes visible. Bedding is aired. Tea arrives in a cup that has been used a thousand times, its rim slightly worn. Meals reflect what is available and what is stored; they do not perform novelty. The scent of fuel—wood, dung, or gas depending on the household—mixes with the smell of flour and boiled vegetables. These are not romantic details. They are the honest textures of hospitality.

There are also spaces you do not enter. A visitor learns quickly that not everything is for sharing. Privacy is not a refusal; it is the condition that makes sharing meaningful when it happens.

What the Valley Remembers

Oral histories: when the village speaks in its own cadence

Much of what circulates about Dah–Hanu comes from outside, packaged as a single narrative and repeated until it sounds like fact. The deeper and more reliable material sits elsewhere: in local memory, in stories told within families, in legends and place-based accounts that make sense of a landscape where roads and borders have shifted over time.

When people speak about their past, the emphasis is rarely on what outsiders expect. Stories turn to seasons, to movement between fields, to agreements and disagreements about water, to marriages, to old routes, to a year when weather damaged a crop, to how a household rebuilt after a difficult winter. If a visitor is patient—and if the situation is appropriate—snatches of these accounts become available. They are not delivered as lectures. They appear while someone pours tea, while someone sorts dried fruit, while a child interrupts and is gently corrected.

For a European reader accustomed to museums and plaques, this can be disorienting: the valley does not present its own history in tidy panels. It holds history in voices, and voices require time.

Sacred presence as a daily boundary

Belief in this region is not necessarily separated into formal institutions the way an outsider might expect. Certain places are treated with care. Certain actions are avoided at particular times. This can be explained as “religion,” but the word is often too broad to be useful. What is more noticeable is the practical effect: a restraint, a respect for places and moments that are not negotiated.

You can see it in how people approach a site with a slight change of pace, in how a path is taken rather than cut, in how a conversation shifts when a subject touches on what is considered powerful or sensitive. There is no need to dramatise this. It is enough to observe that the valley contains more than farms and roads, and that not all of it is available to a visitor’s curiosity.

For the traveller, this has a clear implication: do not push. If you are told something is not for photographs, accept it. If a place is approached quietly, match the quiet. The aim is not to imitate; it is to avoid harming what you do not fully understand.

Borderlands, Permissions, and the Quiet Politics of a Road

Restricted landscapes and the feeling of lines nearby

Even when the day is ordinary and the road is open, the region carries the sense of being near lines that matter—administrative lines, military concerns, areas where movement is managed. Checkpoints and permits are the visible part of this, but the deeper reality is that people here have lived with shifting oversight for a long time. The road is both a connection and a vulnerability: it brings supplies and access, and it also brings outsiders’ demands.

For visitors, it is tempting to treat restrictions as an obstacle to a personal itinerary. It is better to treat them as a clue to the region’s lived conditions. You are passing through a place where movement can be regulated for reasons that have little to do with tourism. Plans that look simple on a map can become slow in practice. A delay is not an affront; it is part of travelling in a border landscape.

When you travel with local drivers and guides, you see how this is navigated without drama: documents kept ready, routes chosen with an eye to weather and rules, stops made when they need to be made. It is not romantic, but it is honest.

Continuity as a form of strength

There is a tendency, in outside writing, to portray communities like Dah–Hanu as either fragile relics or defiant symbols. Both framings can be limiting. What you actually witness is a steadier kind of strength: continuity. People maintain terraces. They adjust to roads and policies. They host guests when they choose to and refuse when they need to. They keep their households running in a climate that demands planning.

Some of this is visible in infrastructure—repairs, water channels, storage. Some of it is social: decisions about what to share with visitors and what to protect. The everyday effort of maintaining boundaries—physical and cultural—does not announce itself, but it shapes the visitor’s experience more than any slogan.

Leaving Without Claiming

What remains after the photographs

When you leave Dah–Hanu, the river is still there, moving at the same pace it kept before you arrived. The poplars continue to mark the wind. The road resumes its long, uneven relationship with stone and weather. If you have travelled well, you carry fewer claims than you arrived with.

You might remember the practical weight of a water container, the tightness of a rope, the way dust settles on a windowsill inside a house, the smell of apricot drying in sun, and the sound of a gate closing with the firm assurance of a household returning to itself. You might remember that a village does not owe you a story that flatters your expectations.

Beyond the Label: Seasons Along the Indus in Dah–Hanu is, in the end, a simple request—to look long enough for the label to lose its usefulness. Not because the place is mysterious, but because it is specific: a year-round community, attentive to water, storage, and weather, living beside a river that has seen more travellers than it will ever acknowledge.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.