When the Pass Opens, Nubra Begins

By Sidonie Morel

Leh at Dawn, When Engines Sound Like Prayer Wheels

Cold metal, warming hands, and the first sip before the climb

In Leh, the morning begins at the edges: a door latch, a kettle lid, a dog lifting its head and deciding whether the day is worth a bark. In winter it feels sharper, in summer it feels thinner, but either way the first light comes quietly, turning the dust in the air into something you can see. A driver checks the tyres without ceremony, palm pressed to rubber as if reading temperature. A second car idles a few metres away. The sound is ordinary—engine, cough, idle—yet at this hour it carries down the lane like a small procession.

Before you leave, there are the practical acts that look like habits but are really preparation: a scarf folded and re-folded, a phone cable found, water bottles set where a hand can reach them without looking. In Ladakh, a road day is rarely “just driving.” You are moving through altitude and weather and checkposts, and sometimes through other people’s ideas of what is safe. It is why the car feels like a room as much as a vehicle: it holds your layers, your snacks, your permits, the spare pair of gloves you think you will not need until your fingers decide otherwise.

The primary keyword, Nubra Valley road trip, belongs here not as a label but as a fact. From Leh, it begins in plain daylight: the climb out of town, the last clusters of shops, then the road tightening, taking its first turns as if testing your attention. The air has its own dryness, the kind that makes lips notice themselves. The windscreen collects fine grit. A small cloth appears; someone wipes the glass without speaking, as naturally as brushing flour from a kitchen table.

Permits, checkpoints, and the quiet choreography of leaving town

On the way toward Nubra, the formalities arrive early and without drama. An entry in a ledger. A brief glance at faces. A paper held flat in a hand so it does not flap away. For travellers, it can feel like interruption; for the people who live with it, it is simply part of the landscape. You pass through it as you pass a bridge or a bend: slowed, observed, released.

There is a particular stillness to these moments. Engines stay running. Doors remain closed. The driver leans an elbow out of the window, not to show ease but to make the waiting manageable. The guards, often young, carry their own routine with a focused politeness. In some accounts of the road into Nubra, especially when the itinerary reaches toward border villages like Turtuk, this sense of “line” becomes a theme rather than a detail: you can feel that you are travelling in a region where geography is never only geography. The road is public, the mountains are indifferent, but the human systems around them are active and specific.

Once the papers are returned, the car gathers speed again and the conversation adjusts. Someone mentions the time. Someone asks whether there will be snow at the pass. Someone answers with a shrug that is half knowledge, half luck. This is the choreography of leaving Leh: not dramatic, not secretive—just attentive. In travel writing that avoids the brochure voice, these are the details that matter because they are real: the pause, the stamp, the handover of a document already warmed by someone else’s palm.

A road that narrows into itself—hairpins, gravel, and the thin air’s insistence

Beyond the last familiar turns, the road climbs in a series of decisions—left, right, left—each one tightening the view until the valley is gone behind you. The surface changes. Asphalt becomes patched, patched becomes rough. A stretch of gravel rattles under the tyres with a sound like dry beans poured into a metal bowl. The car’s suspension speaks in small knocks. When the vehicle slows to pass another, you catch a brief smell of hot brakes and dust.

The thin air is not romantic; it is practical. You notice it when you lift a bag, when you speak too quickly, when you climb a few steps away from the car and your lungs refuse to treat it as a minor effort. Hairpins bring their own discipline: the driver’s hands shift on the steering wheel, the car leans, a horn is used in the old way—warning, not anger. There are moments when the road seems to fold back on itself so tightly you can see the next turn above you like an unfinished thought.

Some travellers write about this climb as though it is a test to “conquer.” Better to consider it a threshold you pass through with care. You are not here to win against the mountains. You are here to arrive, and arriving in Nubra depends on respecting the simple physics of altitude, temperature, and road condition.

Khardung La, Not a Trophy but a Threshold

The uneasy beauty of altitude: breath shortened, light sharpened

Khardung La appears with the bluntness of a signboard and the softness of snowfall, depending on the day. Sometimes it is bare and bright, the ground a mix of rock and tyre-stained slush. Sometimes it is a pale field where vehicles look like dark punctuation. The wind does not negotiate. It takes what it wants from exposed skin and leaves you with a clear understanding of why people cover their faces without thinking.

The light at the pass is different from the light in Leh. It has less warmth, more edge. The sky looks closer, but that closeness offers no shelter. When you step out of the car, the cold arrives immediately in the mouth and nostrils. Your breath becomes visible for a second and then it is gone, taken by the same wind that shakes the prayer flags overhead until they sound like fabric snapping on a clothesline.

There is often a small gathering of travellers here—some moving quickly, some lingering for photographs, some staring down at their hands as if waiting for sensation to return. The pass can feel like a stage, yet the body insists on turning it back into a place of function: breathe, move, drink water, do not overstay. The best advice is rarely spoken; it is demonstrated by those who keep their pause short and their gestures unhurried.

Where the army presence becomes part of the landscape, not a footnote

The army is visible at Khardung La in ways that make the pass feel less like a remote height and more like an inhabited corridor. Vehicles with markings. Barracks. Men in uniform standing with the steadiness of people trained to watch. For many European readers, this can be unfamiliar—the idea that a scenic route and a strategic route are the same thing. In Nubra, and especially on the road that continues toward villages close to the border, that overlap becomes unavoidable.

This is where the “car tour” frame matters. Travelling by vehicle is not only about comfort; it is about moving through a region whose access is regulated and whose conditions shift. A driver who understands checkposts, weather patterns, and timing becomes more than a service provider. He becomes a local interpreter of practical reality. In several road narratives about Nubra, the driver’s small judgments—when to stop, when to push on, which route to take if snow has fallen—are described with the same attention usually reserved for monasteries and landscapes. It is because those judgments shape the day.

At the pass, you see the infrastructure that supports this reality. It is not hidden. It stands plainly against the rock and snow. You take it in, and then you get back into the car, because the pass is not the destination. It is the hinge.

Crossing the pass and feeling the world tilt—fear, relief, and a sudden widening

The moment after Khardung La is not a cinematic reveal. It is subtler: the road begins to descend, the engine changes its tone, and the body senses that oxygen will gradually return. The car moves from tight hairpins into longer curves. Snow becomes patchier. Rock takes on colour again. The wind still exists, but it stops feeling like a hand on your collar.

Then, little by little, the valley opens. Nubra does not arrive in a single view; it arrives as a sequence. First, the suggestion of a wider floor. Then the hint of water. Then green—unexpected, definite—fields and trees holding their place against a high desert that could easily refuse them. A traveller who has read certain accounts of Nubra will recognise this shift: sand, water, rock, and suddenly agriculture—each element not blended but laid side by side as if the valley is demonstrating its range.

By the time you reach the first broader stretches, dust has settled on the dashboard in a fine layer. A packet of biscuits has warmed in the sun. Someone reaches for a bottle and the plastic crinkles loudly in the quiet. The car is still a moving room, but the room now contains a sense of arrival.

Descending Into Nubra: Sand, Water, Rock—Three Worlds in One Valley

The first sight of the Shyok’s braided channels and the green surprise of fields

Nubra’s rivers do not behave like the rivers of temperate Europe. They braid, divide, recombine. From the road, you see pale channels spread across a wide bed, water moving in several directions at once as if it is thinking through options. In some seasons the Shyok looks assertive, in others it looks deceptively calm, leaving wide stretches of exposed stones that catch the light like bone.

Alongside this, the green appears. Not forest green, but cultivated green: the measured rectangles of barley, the disciplined lines of poplars. You see irrigation channels cut with care. You see the edges of fields reinforced with stone, as if to defend the soil from wind and water both. The valley’s fertility is not a generalised “lushness.” It is the result of work, and you can observe that work in the precise borders of each plot.

The road passes through pockets of settlement—clusters of houses, a shop with a few items visible through a doorway, children walking in small groups. There is no continuous townscape. Instead, habitation appears, disappears, appears again. For travellers expecting a single “Nubra experience,” this can be clarifying. Nubra is not one place. It is a string of lived-in pockets along a broad valley that holds sand dunes and monasteries and orchards in the same breath.

Poplar lines, barley patches, and villages that appear like a thought becoming real

Poplars are one of the first trees many visitors notice. They stand in lines that look intentional because they are. They break the wind. They mark fields. They offer shade thin as a veil. When the car passes them, the light flickers through the leaves in a way that feels almost mechanical, like the pattern of a film reel. In summer, the leaves move. In colder months, branches hold still and the same line of trees becomes a bare score against the sky.

Between these lines, you see courtyards with stacked firewood, metal basins turned upside down, laundry hanging where it can catch the dry air. These domestic objects—small, unremarkable—do more to explain a place than any list of attractions. The car tour, at its best, allows you to notice them because you are not struggling with transport logistics. You can let your attention drift outward: to a woman carrying a bundle, to a boy pushing a bicycle, to a goat tethered to a post and tugging at a patch of nothing in particular.

Some travellers arrive with the famous images already in mind: dunes, camels, a high monastery. Those exist, but the valley’s daily life is made of these smaller scenes—objects drying in sun, water moving in channels, a gate latch swinging in wind. They are the texture that makes the larger sights credible rather than decorative.

Why Nubra doesn’t arrive all at once: it changes scene by scene through the windshield

Driving in Nubra is like turning pages in a book that refuses to keep a single tone. One bend gives you sand, the next gives you water, the next gives you a village with apricot trees behind its walls. The changes are not subtle. They arrive as contrasts. This is part of what makes the Nubra Valley road trip so distinct: the sense that the valley contains several climates and several stories within the span of a morning’s drive.

Even the dust behaves differently. Near the riverbed, it is pale and powdery, rising in soft clouds. Near the dunes, it becomes finer, more insistent. On rougher road sections, stones ping the underside of the car with a hard sound. In the quiet parts, you hear only tyres and wind. In busier parts, you hear horns and human voices, a brief market noise, then silence again.

Travel writing that is worth keeping does not pretend this variety can be “covered” in a checklist. It shows the sequence. It gives the reader the feeling of movement. Nubra is a place you enter gradually, and the car—if you let it—becomes a slow instrument for noticing change.

Diskit: A High Ridge, a Monastery, and the Valley Spread Below

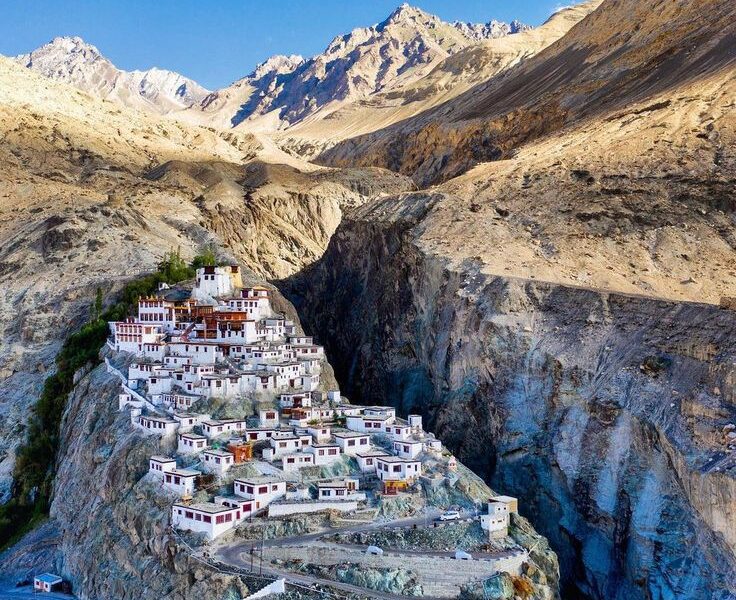

Climbing to Diskit Gompa—wind, incense, and a view that steadies the mind

Diskit sits with a kind of composure above the valley, and the road up to the monastery makes you aware of height again—not in the punishing way of Khardung La, but in a calmer, local way. The climb is shorter, the air less thin, yet the wind can still feel sharp on the face. You step out, and the immediate sounds are simple: footsteps on grit, a distant engine, a flag rope knocking gently against a pole.

Inside the monastery precinct, the world narrows. The light changes. The smell of incense is faint but definite, like a thread you can follow. There may be a monk passing, or a visitor pausing with shoes in hand. The walls hold their colour—whitewash, earth tones—while outside the valley looks like a wide map laid flat.

From here you see the logic of Nubra’s settlement: fields concentrated where water can be directed, villages grouped where land holds, roads tracing the lines that make sense through a large, open space. It is a view that does not demand emotion. It offers information. It helps you understand how much of the valley’s “beauty” is in fact the visibility of human adaptation—how life has been arranged to persist in a high, dry place.

The giant Maitreya as a still witness to traffic, tourists, and passing seasons

Near Diskit, the large Maitreya statue is often photographed. It is visible, unavoidable, and for that reason it risks becoming a symbol emptied by repetition. But if you stand with it for a moment—without rushing to frame it—you notice what it watches: not only the valley, but the moving line of cars and buses and motorcycles, the slow thread of travel that has become part of Nubra’s economy.

Tourism is present in Nubra in a way that is both obvious and uneven. It collects at certain sites. It thickens in certain seasons. It fades abruptly in others. The statue, fixed and expressionless, turns this movement into a kind of observable pattern. You can see which roads are busy, which are quiet. You can see where people stop, where they do not. You can also see how quickly the valley absorbs the activity; a few hundred metres away, behind a wall, there is only a courtyard and a dog sleeping in dust.

From the ridge, the car becomes a small thing again. It is a useful reminder. The road is central to your experience, but it is not central to the valley’s existence. The monastery has been here through winters when no tourist arrived. The fields have been planted and harvested without reference to camera angles. This perspective—quiet, factual—can be more grounding than any attempt at grandeur.

Looking down: the river’s pale threads, the sand’s hush, the road’s thin promise

The valley below Diskit holds several textures at once. The river looks like a set of pale threads pulled across a broad fabric. The sand sits in soft forms that suggest movement even when the wind is still. The road cuts through it all, narrow and practical, never fully in control of the terrain it crosses.

It is easy to forget, when travelling by car, that the road is not guaranteed. Landslides happen. Snow closes passes. Water rises. In the narratives that describe Nubra not as a theme park but as a living valley, this uncertainty is always present, sometimes as a passing remark, sometimes as the entire mood of a day. Even in good weather, the driver watches the surface, the shoulder, the colour of the sky. He is reading signs you may not notice.

From above, you understand why timing matters. Late afternoon light can turn dust into glare. A small storm can make a rough patch feel dangerous. A pause too long at high altitude can turn a simple visit into a headache. These are not warnings meant to intimidate. They are the quiet realities that make the Nubra Valley road trip a true journey rather than a casual outing. The view from Diskit reminds you that travel here is always a negotiation with conditions.

Hunder in Late Light: The Sand Dunes That Keep Their Own Time

An evening wind over dunes—soft grit on lips, footprints erased without drama

Hunder’s dunes are famous, and fame changes how people look. Many arrive expecting a spectacle. What they find, if they pay attention, is something more restrained: a pocket of sand in a high valley where water and cultivation are never far away. The dunes are not endless. They are a contained phenomenon, shaped by wind and river, bordered by greenery and settlement. That contrast is part of their interest.

In late light, the sand becomes precise. Each ripple shows. Each footprint cuts into the surface with a clean edge, then softens. The wind comes, not as a dramatic gust but as a steady movement, lifting grains that tap against ankles and gather in the seams of shoes. You taste it sometimes—dry, mineral. A scarf pulled up over the mouth is not an affectation; it is practical.

People walk across the dunes with phones held out. Children run and slide. Somewhere nearby, a small stall sells tea or instant noodles, the smell of frying oil faint in the air. You can observe all of this without judging it. It is simply a fact of contemporary Nubra: the dunes as a shared stage. Yet the stage is never fully owned. The sand keeps shifting, smoothing itself, making each moment temporary.

Bactrian camels as silhouettes, not spectacle; the valley’s quiet insistence on restraint

The double-humped Bactrian camels are another image travellers carry in their minds before arriving. They are real, and they move with a weight that makes you notice the ground. Their feet press into the sand and leave deeper prints. Their breath is visible on colder evenings. Their long hair catches dust and light. When they kneel, the motion is slow and deliberate, as if the body is composed of heavy joints remembering an older rhythm.

It is possible to reduce them to a tourist activity. It is also possible, simply, to watch them. To see how they stand when the wind changes. To notice the way handlers speak softly, tugging a rope with familiarity. To observe that these animals, like much in Nubra, exist at the intersection of livelihood and visitor desire. The ethics are not resolved in a paragraph; they are lived in daily choices—how rides are offered, how animals are treated, how long they work, how people behave around them.

In writing about Nubra, restraint matters. The dunes and camels are not the valley’s whole story. They are one chapter, best approached with the same quiet attention you give to a field or a courtyard. When the light drops, and the camels become silhouettes against the pale sand, the scene becomes less about novelty and more about shape and movement. That is when it feels most honest.

Night falling fast—temperature dropping, stars arriving like a second landscape

Evening in Nubra can feel abrupt. The sun lowers behind a ridge and the warmth leaves quickly, as if someone has closed a door. People put on jackets. Hands return to pockets. Tea becomes more desirable than photographs. The dunes cool underfoot. The wind, which in daylight felt like irritation, begins to feel like a reminder: you are at altitude, in a desert valley, where night is not gentle.

As the sky darkens, the stars appear in a way that does not require commentary. They are simply visible, numerous, and sharp. For European readers used to streetlights and clouded urban skies, the clarity is striking—but it can be described without exaggeration: the Milky Way as a faint band, the brighter stars as fixed points, the cold making the air seem cleaner.

In the car, returning from the dunes, the heater begins to work. Windows fog slightly, then clear. The road is quiet. A dog crosses slowly, unhurried, as if it owns the lane. A small shop glows with a single bulb. These are the domestic details that make the night feel inhabited rather than remote. You arrive back at your guesthouse or camp with sand in your shoes and cold in your hair, and the practical act of washing your hands in cold water becomes part of the memory.

Toward Turtuk: Crossing Lines Without Crossing Them

A road that feels watched: signs, uniforms, and the weight of proximity to borders

The drive toward Turtuk changes the atmosphere of the day. The valley remains wide, the light remains clean, but the human markers of border proximity become more frequent. Signboards. Checkposts. Military vehicles. The road itself feels more like a corridor. You understand, without needing to be told, that this is a region where movement has consequences beyond tourism.

Travellers who write about this route often describe a subtle shift in their own behaviour: voices lowering, cameras used with more hesitation, a general sense of being a guest in a place that is not merely scenic but politically sensitive. These are not theatrical responses; they are grounded in observation. The presence of uniform is not rare here. It becomes, as one strong road narrative puts it, part of the landscape—visible, consistent, and shaping what the road feels like.

For a car tour, this is where experience depends heavily on local guidance. A driver knows when it is appropriate to stop, when it is better to keep moving, what questions to answer simply and what to leave unasked. Travelling with that knowledge is not about fear; it is about respecting a living context. The road invites attention, and attention here includes noticing the human systems that share the valley with rivers and dunes.

Apricot trees, courtyards, and the tenderness of ordinary life in a complicated place

Turtuk, when you arrive, often feels more domestic than expected. There are apricot trees, and in season the fruit appears in bowls and baskets with the casual generosity of something abundant. Walls enclose courtyards. Wooden doors are worn smooth where hands have touched them for years. Chickens move in brief runs, then pause. A cat appears on a ledge as if it has always been there.

The village’s everyday life is visible in small objects: a sieve leaning against a wall, a stack of metal plates, a broom made of bundled twigs. There may be a stream of water passing through, diverted into channels for gardens. The air carries the scent of wood smoke or cooking oil, depending on the hour. None of this is “exotic.” It is ordinary life, set within a complex geography.

When a place is close to a border, people outside sometimes assume the daily atmosphere must be tense. In Turtuk, the tenderness of ordinary life is what you observe first: children calling to each other, an older person resting in shade, someone washing something at a spout. The political context does not vanish, but it does not erase the domestic. A traveller who approaches with patience can see both without forcing one to dominate the other.

Food as welcome: the way a shared dish turns “visitor” into “guest,” if only briefly

Leaving Turtuk is the same road in reverse. The signs and uniforms reappear in the opposite order, then thin out. The orchards fall behind, the valley opens again, and by the time the car returns to the familiar bend near Hunder and Diskit, the day has quietly split into two directions: one toward the border village we have just left, the other toward the upper Nubra road that leads to Panamik.

On this route, food often becomes the clearest form of hospitality. A cup of tea offered without flourish. A plate placed on a low table. Bread warm enough that the steam is visible when it is torn. In some of the most memorable travel accounts from this part of Ladakh, the meal is not described as a “cultural experience” but as a moment of simple, precise attention: the weight of the cup, the smell of the kitchen, the way conversation pauses while everyone eats.

For European readers, this can be the point where the landscape becomes less abstract. You have been driving through valleys and over passes, watching rivers and dunes. Then you sit. You taste something. You see the interior of a house, the arrangement of objects that make daily life possible. It shifts the scale of travel from panoramic to intimate.

This is also where the car tour’s pace matters. If the day is rushed—if the itinerary is treated like a checklist—you miss the unplanned invitation, the moment when someone says “sit” and means it. The best road stories from Nubra insist, gently, on time: not hours spent idly, but minutes allowed to deepen. A shared dish does not change the world. It does change the tone of a day.

Panamik and the Warmth Under Snowline: Water That Remembers the Mountain

Hot springs as a small miracle—heat rising into cold air, skin awakening

From the Hunder–Diskit bend, the car turns away from the road to Turtuk and takes the other line of the valley. The traffic thins. The poplar rows become longer, the settlements more spaced, and the sense of heading deeper into upper Nubra grows with each kilometre. Panamik’s hot springs are often mentioned in practical itineraries as a “stop,” but they can be more than that. After days of dry air and dust and night cold, warm water feels like a direct conversation with the body. You see steam rise into the air and dissolve. You feel heat move into hands and wrists, then fade as you pull away, then return when you dip again.

There is nothing theatrical about it. The setting is simple. People come, soak, talk quietly, leave. The surrounding valley remains the same high desert. Fields remain edged with stones. Poplars stand in lines. Yet the water offers a different texture from everything else: it is softness in a landscape that is often hard.

For a traveller, this is where fatigue can become visible. The shoulders drop. The face relaxes. The day’s dust becomes apparent on skin as it lifts away. The road still exists—you will return to it—but for a moment the journey is not measured in kilometres. It is measured in the sensation of warmth against cold air.

Listening to locals talk of weather, road closures, and timing—travel as judgment, not speed

In Panamik, conversation often turns to weather. Not as small talk, but as practical information. People talk about snow at the pass. About which road is open. About how long it took someone to reach Leh yesterday. Timing here is not a preference; it is a safety measure.

This is the kind of detail that slips easily into a narrative and matters more than any “top tips” list. A local person’s mention of a road closure is not an anecdote; it is a reminder that travel in Ladakh is conditional. It depends on season, on recent storms, on maintenance, on the simple unpredictability of mountains.

Some travel writers describe this as part of the valley’s character: the sense that you do not command your schedule, you negotiate it. In a Nubra Valley road trip, that negotiation is constant. It shows in the driver’s habit of checking the sky, in the decision to leave early, in the choice to take the Shyok route or not depending on conditions. When you listen rather than impose, you begin to travel with the valley rather than through it.

The valley’s quieter luxuries: sleep, soup, and the unadvertised comfort of stillness

Nubra’s luxuries are often quiet. A bed with enough blankets. A bowl of soup that arrives hot and stays hot. The sound of water moving in a channel outside a window. A courtyard where apricots are laid out to dry, their skins catching light. These are not the things people put on postcards, yet they are what stay in memory.

In the evening, you may hear dogs bark, then stop. You may hear a distant engine and then nothing. The stillness is not absolute; it is simply unfilled by constant urban noise. This changes how you notice small sounds: a spoon against a metal bowl, a door closing, the soft scrape of a chair on a floor.

For European travellers used to long days built around museums or city streets, this can feel like a different kind of travel—one measured by attention rather than activity. Nubra does not ask you to be entertained. It asks you to observe: the way light moves across a wall, the way dust settles on a windowsill, the way a family’s kitchen holds objects in a logic that makes sense when you look closely.

The Return Road: What the Pass Gives Back, What It Takes Away

Leaving Nubra with sand in seams and river-light in the eyes

When you leave Nubra, the evidence is small and persistent. Sand remains in shoe seams even after you tap them at the threshold. Dust has worked its way into the folds of your bag. Your scarf carries a faint smell of sun and road. If you have spent time near the river, you may still have the image of braided channels in your mind, the water’s pale threads moving across a wide bed.

The car is again a room, now holding what you gathered: a jar of apricot jam, perhaps, wrapped carefully; a packet of nuts bought from a small shop; a memory of a cup of tea offered in Turtuk; the warmth of Panamik water in your wrists. None of this needs to be declared as “meaningful.” It is simply what travel leaves behind when it is attentive.

Back over Khardung La—no triumph, only gratitude and the discipline of attention

The climb back toward Khardung La feels different from the descent into Nubra. You are returning to altitude. The engine works harder. The car’s interior warms and cools unpredictably as the heater fights the outside temperature. The road’s surface demands the same patience as before. If snow has fallen, the edges look sharper and more fragile. If the day is clear, the light becomes hard again, and the wind at the pass still insists on being acknowledged.

At the top, travellers again stand with phones raised. But there is less urgency now. You know what lies beyond the pass. You know how quickly weather can change. You know the body’s limits a little better. The pass is still a threshold, but you have already crossed it once. You treat it less like a stage and more like what it is: a high point where conditions must be respected.

Arriving in Leh changed in small ways: a slower gaze, a longer silence, a steadier rhythm

By the time Leh reappears, the change is not dramatic. It is incremental. The town’s sounds—traffic, voices, shop shutters—feel louder after the valley’s quieter intervals. The air feels thicker at this lower altitude, yet also dustier in a different way, coloured by the town’s daily movement. You notice it because your attention has been trained by road and weather to notice simple things.

You step out of the car and your legs feel the stiffness of hours spent sitting. Your hands smell faintly of dust and fabric. You carry your bag up a stairwell, and the weight is ordinary but newly felt. In your pocket there may still be a folded permit, now softened by handling.

The Nubra Valley road trip ends without a grand statement. It ends as travel often ends: with a door closing, with shoes placed beside a bed, with a glass of water drunk slowly. Later, when someone asks what Nubra was like, you may find yourself describing not the superlatives but the specifics: the wind at the pass, the braided river, the precise ripples of sand at Hunder, the apricot trees in Turtuk, the steam rising at Panamik. The valley’s “silence” is not emptiness. It is a space where small details become audible.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.