When the Footpath Is the Real Map

By Sidonie Morel

In Ladakh, the first thing the road teaches you is speed. It delivers you to places before you have had time to feel the air change on your skin.

The engine stops, you step out, you look—then you move on, as if the landscape were a series of pictures hung too close together.

But there is another Ladakh, older than mileage and quieter than schedules, where the path is not an accessory to travel, but its reason.

It begins in small ways: a turn off the asphalt into dust the color of wheat flour, a stone step worn shallow, a channel of meltwater running with the steady confidence of something that must arrive on time.

Walking Ladakh the old way is not a vow against modern life. It is an agreement to let the body learn what the car cannot hold.

The Road That Arrives Too Quickly

A morning where the engine stops, but the day does not

You can feel it most sharply at the edge of Leh, where the town loosens its grip and the land begins to look like it has been arranged by thrift:

fields stitched small and precise, walls set with an accountant’s patience, houses tucked behind apricot trees as if to hide their warmth.

On the road, it is a matter of minutes—one last junction, a burst of speed, then the valley opens and you are already somewhere else.

On foot, it is not dramatic. It is simply slow enough to become real.

The first hour is always an argument between the mind and the lungs.

The mind wants to narrate. The lungs want you to shut up and keep walking.

The air is clean in a way that feels almost dry enough to crack; it sits in the throat like a promise you are not fully sure you deserve.

You pass men rolling prayer beads with the same economy they use to lift stones.

You pass women rinsing metal bowls in cold water and setting them to dry in a line of sunlight that looks, briefly, like a cloth being shaken out.

A dog follows for a while, then decides you are not interesting and returns to its shade.

Walking does not flatter you here. It corrects you.

It tells you, in small humiliations, what altitude means, what thirst means, what it means to climb a slope that a vehicle would not even mention in its gears.

And then, in the same breath, it rewards you with something hard to name: the sense that your presence is no longer just passing through, but attached, for a few hours, to the ground.

What becomes visible only at walking speed

At walking speed, Ladakh stops being a postcard and returns to being a place where people live.

You notice the way mud plaster holds heat, how stone walls are built not for beauty but for endurance, how a doorway can look plain until you see the careful sweep marks at its threshold.

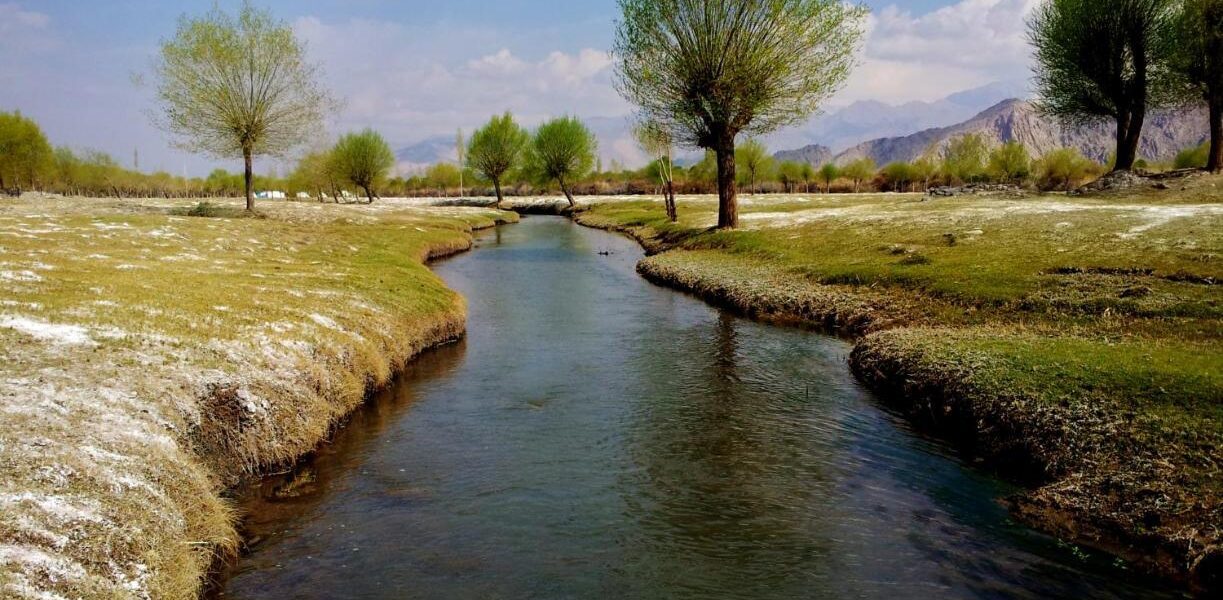

You notice how water is not background, but a line of authority.

A narrow channel—sometimes no wider than a hand—runs beside the path, turning gently, dipping under stones, resurfacing as if it has a private relationship with gravity.

You can hear it before you see it, a thin, persistent sound like a small animal breathing.

You also notice the objects that belong to walking: the battered plastic bottle refilled without ceremony, the cloth tied to a bag to keep dust off, the stick that is not a hiking accessory but a useful third leg.

A road encourages you to think in destinations.

A footpath encourages you to think in weight: what you carry, what you can do without, what the day will demand from your knees.

Somewhere along the way, you begin to like that kind of thinking.

It feels honest. It feels human.

What You Carry When a Car Cannot Follow

The small domestic inventory of a day on foot

Walking Ladakh the old way does not mean you are reenacting another century.

You still have a phone, perhaps, and a folded map you do not entirely trust.

But the logic of the day changes the moment you leave the road, because the car no longer carries your carelessness for you.

You start to count, not obsessively, but in the calm, practical way that people count when the counting matters.

Water. Something salty. Something warm. A layer you can put on without thinking.

In villages, I have watched what people bring when they set out early: a tin cup with dents like a story, a cloth bundle of bread, a small packet of tea leaves, a handful of dried apricots that taste of sun and patience.

Sometimes a prayer bead strand turns up, not displayed, simply present—something the fingers find when the mind is busy with steepness.

Sometimes a razor appears later in the day, a minor act of keeping oneself in order, performed if there is enough water and if the work has loosened its hold.

These are not romantic details. They are the architecture of daily life.

There is a kind of intimacy in knowing the weight of your own day.

The strap bites where it always bites. The shoulder complains in its predictable language.

You adjust, you shift, you tighten, you loosen, and the day goes on.

It is not heroism. It is competence, and there is a quiet dignity in it.

How walking teaches you to leave things behind without drama

A car allows you to bring versions of yourself you do not need: the “just in case” self, the anxious self, the self that would rather carry an extra jacket than tolerate a shiver.

On foot, you become less sentimental about objects.

You learn the difference between comfort and clutter.

You begin to respect the simplicity of having only what you can manage.

This is not an ideology. It is an effect.

A day of walking at altitude does not leave much room for theatrics.

You learn to treat the body like a companion you must not betray.

You stop trying to impress the landscape.

You begin, instead, to cooperate with it.

That cooperation shows up in tiny choices: the way you ration water without announcing it, the way you time your steps to avoid slipping on loose stone,

the way you accept a pause when your lungs insist, even if your pride would prefer to keep going.

Walking Ladakh the old way is full of such negotiations.

They make the day feel less like travel and more like a lived hour-by-hour agreement.

The In-Between Is the Place

Khuls, walls, and the ordinary brilliance of making land habitable

There is a moment, somewhere between one village and the next, when you stop thinking of Ladakh as “high” and begin thinking of it as “made.”

Not in the sense of manufactured, but in the sense of shaped by hands over time.

The valley is not a wilderness interrupted by habitation; it is a habitation that has argued with dryness for centuries and won, carefully, inch by inch.

A khul—an irrigation channel—does not announce itself with grandeur.

It is narrow, sometimes lined with stone, sometimes simply dug and maintained with the steady attention of people who do not have the luxury of forgetting.

It carries meltwater with a kind of discipline.

In the morning it can sound sharp, almost metallic, as if the cold has edges.

By afternoon it softens, and the air above it feels slightly cooler, a small mercy.

Walking beside these channels, you understand something practical and profound at once: water here is not scenery.

It is a schedule, a claim, a responsibility.

It is the difference between a field and dust.

When you pass a gate in a wall, you are passing through someone’s work.

When you pass a tree heavy with apricots, you are passing through someone’s patience.

The old way of walking makes these facts unavoidable, and for that I am grateful.

A lane, a threshold, and the way houses hold warmth like a secret

Village lanes in Ladakh are often narrow enough to make you walk with awareness.

Your shoulder nearly touches a wall; your sleeve brushes dry mud plaster; your footsteps sound different on stone than on packed earth.

There are places where the lane dips and the air cools, and places where it rises and sunlight gathers in a little pool.

You can smell kitchens before you see them: smoke, oil, something boiling, sometimes the faint sweetness of dough.

I have always thought a doorway tells you more about a place than a panorama.

A doorway is where life negotiates with the outside world.

In Ladakh, doorways can be low and plain, built to keep heat in and weather out.

A small pile of shoes waits like a polite warning: slow down, remove yourself from the dust, become less of a stranger.

Even when you do not enter, you feel the gravity of that threshold.

It makes you walk more quietly, as if the village itself were listening.

On foot, these lanes are not obstacles. They are the texture of the day.

They are the reason the old way does not feel like a museum exercise.

It feels like moving through a place that is still doing what it has always done: keeping people warm, keeping grain dry, keeping water moving, keeping animals fed, keeping children from wandering into danger.

Walking allows you to see that work without interrupting it.

Water Crossings, Loose Stone, and the Price of Staying Upright

A river that looks polite until it touches your knees

In travel writing, rivers are often treated like symbols.

In Ladakh, a river is first of all a fact.

It has temperature. It has force. It has a way of making you suddenly attentive.

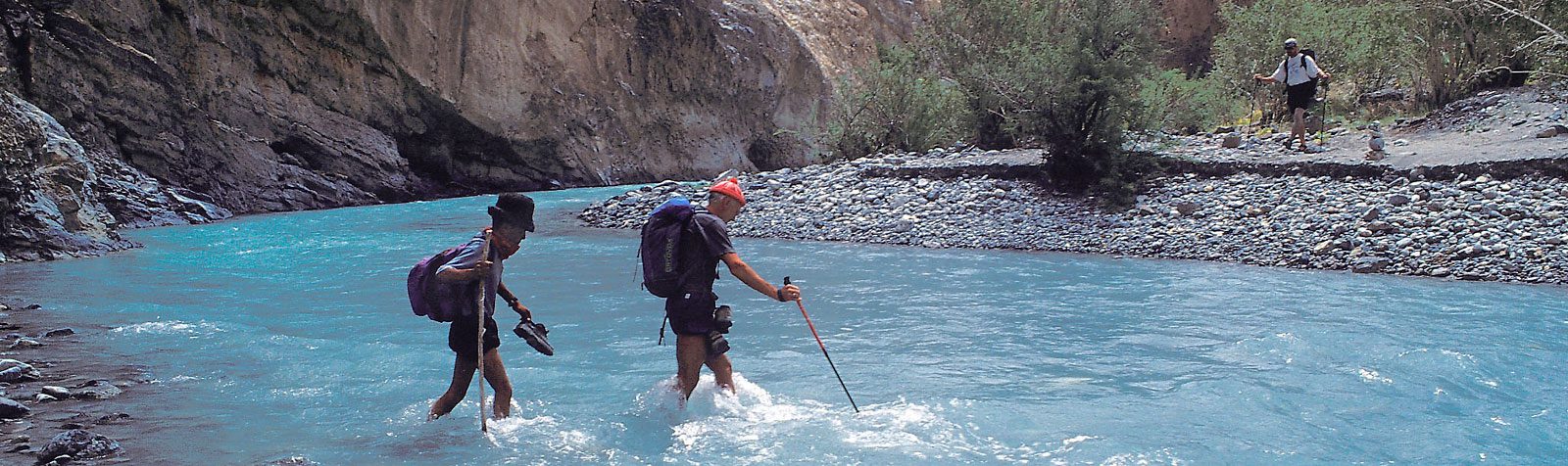

A stream that looks gentle from the bank can turn insistent the moment your boots meet it.

The cold is not dramatic. It is immediate.

It travels through the soles of your feet and straight up into your bones, and for a few seconds you cannot think of anything else.

Sometimes the crossing is simple: a few stones, a careful step, a breath held without noticing.

Sometimes it is not.

In early season, meltwater runs hard and fast, and the crossing becomes a small piece of choreography:

someone goes first, testing, someone steadies, someone carries a load higher, someone laughs because laughter is one of the few tools that weighs nothing.

Animals, when they are present, make the crossing feel more serious.

They do not enjoy uncertainty, and neither do we, but everyone crosses anyway, because the day insists.

What I love about these moments is how quickly they strip away performance.

No one is trying to be impressive.

Everyone is simply trying to arrive on the other side without getting hurt.

It is not a metaphor, unless you are the kind of person who cannot resist making everything into one.

It is just a cold, moving current and a human body doing what it must.

Rockfall and fatigue, treated with the respect they deserve

Loose stone is the language of many Ladakhi paths.

It shifts underfoot with a quiet, irritating confidence.

Your ankles learn to read the slope.

Your eyes learn to search not for beauty but for stability.

There are stretches where the mountain feels calm, and stretches where it feels as if it might change its mind at any moment.

You see old scars in the rock where slides have happened before.

You notice that people walk quickly through certain sections, not because they are in a hurry, but because lingering would be foolish.

Fatigue arrives the way it always does: not as a sudden collapse, but as a slow, accumulating persuasion.

The body begins to negotiate: one more bend, then a pause; one more rise, then water.

At altitude, even small inclines can feel like arguments you did not agree to have.

And yet, there is something reassuring in the honesty of it.

The road can hide effort behind horsepower.

The path does not hide anything.

If you are walking Ladakh the old way, the most practical advice is also the least glamorous: take your time.

Not in the sense of drifting, but in the sense of refusing panic.

Drink when you should. Eat something small before hunger becomes anger.

Let your lungs set the pace.

It is not romantic. It is respectful.

And respect, here, is not an abstract virtue; it is a way of staying upright.

Hospitality as Geography

How a doorway turns passage into relationship

There are places in Ladakh where the path seems to funnel you toward human contact whether you intend it or not.

A village is not something you “visit” as a neutral observer; it is a place that has to decide what to do with you.

In many homes, hospitality is offered with a practical kindness that feels both generous and unsentimental.

You are given tea because tea is what people offer, and because the day is long, and because it is cold, and because you are there.

No speech is required.

Inside, the light changes.

It becomes softer, warmer, and more intimate.

Walls hold heat the way hands hold a cup.

The floor may be covered with rugs or cushions that smell faintly of wool and smoke.

Someone will motion where to sit.

Someone will ask where you came from, not as an interview but as a way of placing you in the day’s geography.

In the kitchen corner, something simmers.

You can hear the thin, domestic music of ladles and metal bowls.

What surprises me, each time, is how quickly the body relaxes in such rooms.

Outside, walking keeps you in a state of alertness: sun, wind, stone, water, dogs, altitude.

Inside, you are allowed to become a person again rather than a moving object.

The old way of walking makes these moments possible.

A car delivers you to accommodation without needing anyone in between.

A footpath, on the other hand, carries you through the spaces where people still have the power to greet you.

Exchange without turning it into a transaction

It is easy, as a visitor, to romanticize hospitality.

It is also easy to feel guilty about it.

Both reactions are a little self-involved.

What I have learned, slowly, is to accept kindness without making it into theatre.

If someone offers you bread, eat it.

If someone refuses payment, do not turn the refusal into a moral drama.

Say thank you in the clearest way you can.

Offer something practical if it is appropriate.

Help carry a bucket.

Ask if you should take water from the channel or from the tap.

Be ordinary. Being ordinary is often the most respectful thing.

“Walk slowly,” a woman once told me, as if she were advising me about the weather. “The path is older than your hurry.”

Hospitality in Ladakh is not separate from the landscape; it is part of how the landscape works.

It is one of the mechanisms that makes life here possible.

The old way of walking does not just reveal scenery.

It reveals the social systems—the small, resilient forms of care—that keep people going through short summers and long winters.

If you let yourself see that, you begin to understand that a footpath is not merely a line on the ground.

It is a line through a living community.

The Argument Between Roads and Children

When the future speaks softly, so it does not injure the present

Roads change more than travel time.

They change who stays, who leaves, and what counts as a good life.

In Ladakh, as in many mountain places, the younger generation carries an extra kind of weight:

the weight of possibility.

A phone in the hand is not just a device; it is a window, a comparison, a temptation, sometimes a lifeline.

School schedules pull children away from seasonal rhythms.

Jobs in town pull families toward cash and away from fields.

None of this is villainy. It is simply the world arriving, as it always does.

And yet, when you walk, you see what is at stake with a clarity that a car can blur.

You see how much knowledge is stored in bodies: in the way someone reads cloud build-up without checking an app,

in the way someone knows which channel will run dry first, in the way someone can tell from a goat’s gait that trouble is coming.

These skills do not transfer neatly to a classroom.

They belong to the path.

They belong to repetition, to seasons, to attention sharpened by necessity.

In some villages, you can feel the debate without anyone stating it.

A young person speaks of the city with excitement that is careful not to sound like contempt.

An elder speaks of the village with pride that is careful not to sound like a trap.

The road runs between them, physically and symbolically, and it does not choose sides.

It simply exists, offering ease.

Walking offers something else.

It offers time—time to notice what might be lost, and time to appreciate what remains.

Night, bells, and the sound that turns into water

There is a particular kind of silence in Ladakh at night, not empty but full.

It holds the memory of heat in the stones.

It holds the faint smell of smoke clinging to your clothes.

If you sleep in a village or near a field, you may hear animals shifting in their pens: a soft shuffle, a small snort, a bell.

When the bells settle into a rhythm, they can begin to sound like running water—steady, repetitive, oddly soothing.

It is a sound that feels older than any road.

Lying awake, you might remember the day in pieces: the cold bite of a stream at your ankles, the warm press of tea in your hands,

the grit of dust in your hair, the way sunlight struck a wall and made it look briefly alive.

Nothing in these memories is grand.

That is the point.

Walking Ladakh the old way does not give you a neat moral.

It gives you a texture.

It gives you the sense that the place is not performing for you.

It is simply living, and for a short time, you have moved through it at a pace that allows you to notice.

In the morning, the road will still be there, of course.

Someone will drive to town.

A bus will pass.

A child will check a screen.

But the footpath will also be there, quiet and stubborn, carrying water, carrying dust, carrying the day.

And if you choose it, it will carry you too—not quickly, not easily, but honestly.

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.