Leh at First Breath: Learning the Pace of Ladakh’s Thin Air

By Sidonie Morel

A room of sun and silence—your first hours in Leh

The arrival ritual (and why doing less is doing it right)

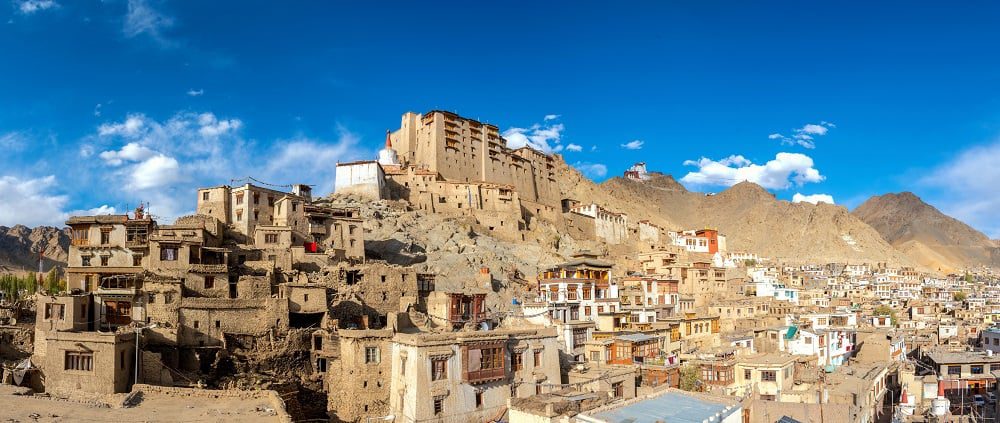

You notice it first in the stairs. Not a dramatic collapse, nothing worthy of a melodrama—just a quiet surprise, as if the building has become a fraction steeper than it was on the map. Leh receives you with a particular kind of light: pale, unhurried, almost ceremonial. And with that light comes the first lesson in preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh. It is not a lesson of grit. It is a lesson of tempo.

European travellers often arrive with a small, well-meaning impatience: the desire to “use the day,” to squeeze the itinerary until it sings. Yet the first hours at altitude reward the opposite. The body is not a suitcase you carry; it is the place you live. When you land in Leh, your lungs and blood begin the slow work of altitude acclimatization. This is the moment when altitude sickness in Ladakh is most easily avoided—not through special equipment, but through restraint so simple it almost feels like an indulgence.

Begin with an arrival ritual that is deliberately ordinary. Drink water. Eat something warm and mild. Unpack slowly, as though the act of folding clothes is part of the journey. If you wander, do it like someone reading a poem aloud: a few lines, then a pause. A short stroll in the old lanes, a glance at prayer flags lifting and settling, a seat in the sun for ten minutes longer than you planned. The point is not laziness. The point is a gentle introduction to high altitude travel, so your body can adjust before you ask it for anything heroic.

This is where preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes less a checklist and more a posture. If you feel slightly breathless, let it be a reminder to soften your pace rather than an invitation to worry. If your appetite is shy, listen and keep things simple. If your sleep is strange, accept that the first night in Leh often is. These details are not failures; they are early signals in the acclimatization process. And when you treat them with calm attention, you create the most dependable foundation for safe trekking in Ladakh later on.

Many people search for a single secret to preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh. The secret is disappointing in its simplicity: arrive, and then allow the body time to arrive too. Do not try to prove anything on Day 1. You are not here to win. You are here to breathe, to watch, to adjust. Ladakh does not ask for haste; it asks for presence.

The gentle rule of Day 1

There is a rule that feels almost insulting to ambitious travellers: on the first day in Leh, do less than you think you can do. If you want practical guidance, here it is, without fuss. Keep exertion low. Avoid long, steep climbs. Do not plan a “quick” drive to a very high viewpoint simply because the road exists. In the language of medicine this is called avoiding rapid ascent; in the language of travel it is called keeping your promises to yourself. It is the simplest form of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh.

Day 1 should be designed around comfort and calm. Take a short walk at an easy pace. Sit down when you feel like sitting down. Choose a meal that is familiar rather than challenging. Keep alcohol for later; in the first days, it steals hydration and confuses symptoms. Keep caffeine moderate; a little is fine, but don’t use it to force energy you have not earned. If you are the kind of person who becomes anxious when resting, give your mind a task that does not demand your breath: writing notes, sorting photos, reading a chapter, or simply watching the sky shift colour.

On paper, Leh is not the highest place you will visit in Ladakh. But it is high enough to make the first day decisive. Many cases of altitude sickness in Ladakh begin with an innocent mistake: a traveller feels “fine” in the afternoon, assumes the body has adapted, and then stacks the next hours with activity. The headache comes at night, the nausea follows in the morning, and suddenly the trip feels fragile. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is often a matter of not testing your luck before you have to.

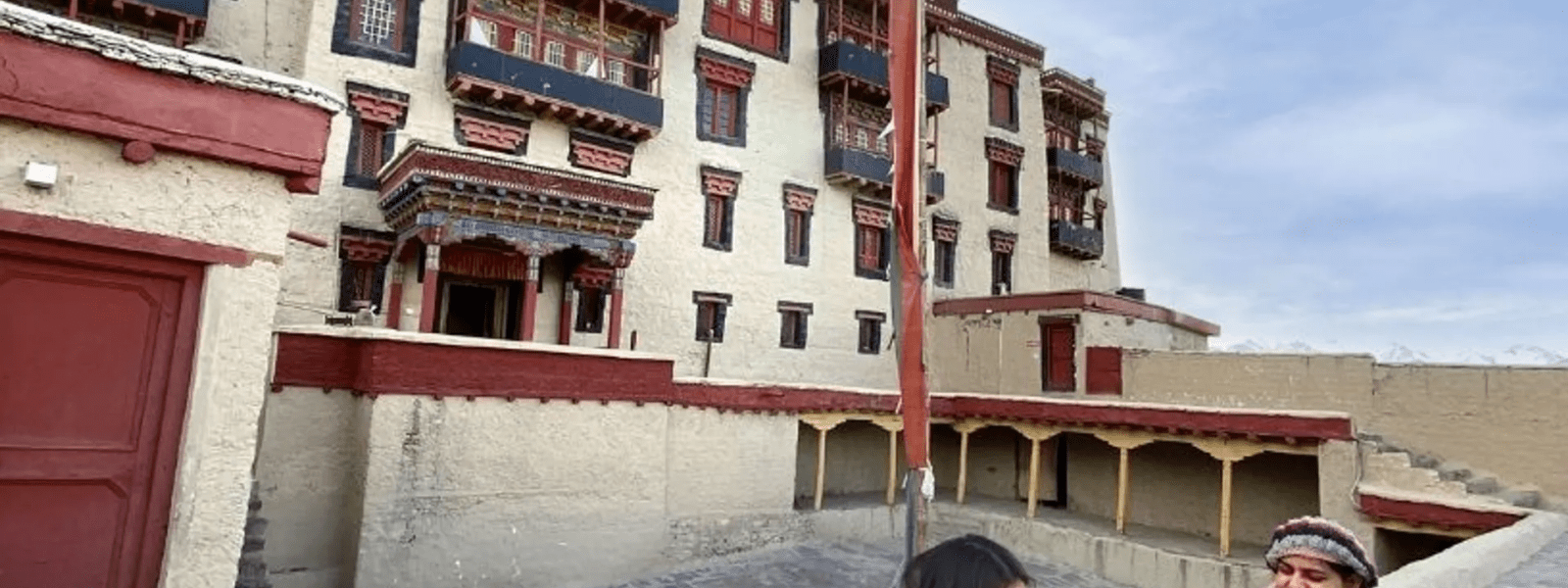

If you want a small, elegant discipline for Day 1, choose one gentle outing and do it slowly. Perhaps a quiet monastery visit nearby, perhaps a stroll where you can return to your room easily. Then return. Drink water. Eat. Sleep early. This is not wasted time; it is the first investment in a safe Ladakh acclimatization itinerary. When you treat Day 1 with seriousness, you create the freedom to explore later without fear or strain.

Above all, let the first day feel like a soft landing. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is not about being tough; it is about being wise enough to be kind to your body when the air is thin.

What altitude does—without melodrama

The simple physics of less oxygen (and why you feel it in small things)

High altitude travel changes the rules quietly. The air is not “bad,” it is simply less generous. At altitude, there is less oxygen available with each breath. Your body must adjust: breathing increases, heart rate rises, and over time your blood chemistry shifts to carry oxygen more efficiently. This is the acclimatization process, and it is the reason preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is not a matter of willpower. The body adapts, but it does so on a timetable that cannot be rushed.

You feel this physics in small, almost domestic ways. Brushing your teeth might leave you slightly winded. Carrying a bag up one flight of stairs feels curiously intimate with your pulse. You may notice your mouth drying faster, your thirst arriving sooner, your sleep becoming lighter. None of this means you are unfit. In fact, fitness can be misleading: a strong heart and trained legs do not grant immediate immunity to altitude sickness in Ladakh. Fit people can suffer just as easily if they ascend too fast, sleep too high too soon, or ignore early symptoms.

Understanding the mechanism gives you calm. When a traveller knows what is happening, they tend to panic less, and panic is a hungry thing—it asks you to fix what cannot be fixed instantly. Instead, you can respond with what works: rest, hydration, and a conservative approach to sleeping altitude. This is why the golden principle of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is not about how high you go in a day, but about how well you allow your body to adjust when you return to sleep.

The simplest explanation is also the most useful: altitude is a stressor. Your body is doing extra work simply to maintain normal function. So you must reduce other stressors. That means fewer strenuous walks, fewer heavy meals at the start, fewer late nights, fewer long drives that climb quickly. It means treating the first days as a period of adjustment rather than performance. When you do this, preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes a quiet collaboration with your own physiology.

If you want a travel-minded image, imagine your body as a fine instrument. In the lowlands it plays easily; at altitude it requires tuning. You do not blame the violin; you tune it. You do not bully the instrument; you listen. That is the spirit that underpins safe trekking in Ladakh and the most reliable way to reduce the risk of acute mountain sickness (AMS).

Normal discomfort vs. warning signs

There is a difference between the mild discomfort of adjustment and the kind of symptoms that demand immediate respect. Many travellers experience mild signs during the first days of altitude acclimatization: a light headache, a slight loss of appetite, a little nausea, restless sleep. These can be normal in the early phase of high altitude travel. They often improve with rest, fluids, and a conservative plan. And this is precisely where preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is most effective: you treat mild symptoms as information, not as an inconvenience to be ignored.

But there are warning signs that should change your plan, quickly and without pride. A severe headache that worsens and does not improve with rest. Vomiting that continues. Confusion or unusual clumsiness. Breathlessness at rest, as if you cannot speak comfortably. A cough that intensifies and is accompanied by chest tightness. Difficulty walking in a straight line. These are not “part of the adventure.” They are reasons to stop ascending, to consider descending, and to seek medical assistance. The romance of travel has no place in negotiating with a dangerous symptom.

If you are travelling with friends, make an agreement in advance: you will take symptoms seriously, and you will not shame one another for caution. In Ladakh, the environment is generous but not forgiving of arrogance. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is also a social practice: you watch each other, you speak honestly, you avoid the temptation to push someone onward because the view is “just one more hour away.”

A practical rule that many guides live by is simple: if symptoms are mild and stable, you can rest and maintain your current sleeping altitude. If symptoms worsen, you do not go higher. If symptoms become severe, you go lower. This is not drama; it is common sense shaped by experience. Most altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes serious only when people continue to ascend despite worsening signs. Prevention is rarely heroic. It is usually a decision made early, in a quiet room, with a glass of water and a willingness to slow down.

Learn this distinction, and your confidence grows. You can enjoy Ladakh without fear, because you know what to watch for and what to do. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh does not mean eliminating all discomfort; it means keeping discomfort in the safe zone, where it resolves rather than escalates.

The Ladakh acclimatization blueprint (that still feels like a holiday)

A 4–5 day “soft landing” itinerary based in Leh

The most elegant itineraries are often the most humane. A good Ladakh acclimatization itinerary does not feel like medical management; it feels like a gentle introduction to place. If your goal is preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, imagine the first four or five days as a soft landing—enough structure to keep you safe, enough ease to let the experience remain beautiful.

Day 1, as we said, is rest with a small walk. Day 2 can be a low-effort day trip that keeps you close to Leh. Choose something that gives you culture without exhaustion: a monastery visit, a riverside view, a short outing where you can return to your room easily and still sleep in Leh. This “climb high, sleep low” approach is one of the most reliable techniques in altitude acclimatization, and it fits Ladakh perfectly because day trips are tempting and the roads make it easy to gain altitude quickly.

Day 3 can extend slightly—still not a day of athletic ambition, but a day with more time outdoors. You can explore with a guide, wander with pauses, or take a gentle drive that includes short walks. Day 4 is when many travellers are ready to consider routes toward Nubra or other regions, provided they feel stable: no worsening headache, decent appetite, and breath that feels comfortable at rest. Day 5, if you have it, is a gift—an extra buffer day that makes the rest of the trip safer and more flexible.

In this approach, preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes woven into pleasure. The first days are not “lost.” They are spent noticing details you would otherwise miss: the texture of dry stone walls, the quiet of early mornings, the way the sun warms a cup of tea. A traveller who acclimatizes well often sees Ladakh more clearly, because their body is not preoccupied with distress.

This blueprint is also practical for Europeans with limited holiday time. You do not need to turn the trip into a clinic. You simply need to respect the first days. Those days pay you back later, when you can enjoy higher places with steadier breath and calmer sleep. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is, in the end, a way of protecting your time as well as your health.

Why “sleep altitude” matters more than “day altitude”

In Ladakh, the roads are both a blessing and a trap. They allow you to see astonishing landscapes quickly, but they also allow you to ascend too fast without noticing, because your legs are not doing the work. This is why the concept of sleep altitude matters so much in preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh. The body does not adapt during the exciting moments when you step out for a photograph. It adapts over hours—especially overnight—when you are resting.

You can visit a higher place during the day if you feel well, but you should be conservative about where you sleep, especially early in the trip. A day excursion can be a controlled experiment: you go higher briefly, you watch how you feel, you return to a lower, safer sleeping altitude. This is the heart of “climb high, sleep low,” a principle that has saved more holidays than any gadget. It is also deeply compatible with the rhythm of Ladakh travel: you can spend the day among monasteries and valleys, then return to Leh’s familiar comfort.

Sleep altitude also matters because symptoms often appear or worsen at night. A traveller who feels fine in late afternoon may wake with a headache and nausea. If you have slept too high too soon, you have fewer options and less comfort. If you have slept conservatively, you have room to adjust. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is often the art of leaving yourself options.

This does not mean you must be timid throughout the trip. It means you must be strategic in the beginning. Once you have acclimatized—once your body has begun to adapt—you can plan more ambitious road trips and short treks. But the early days should be built around the wisdom of sleep altitude. It is the difference between a trip that feels steadily better and a trip that becomes a series of recoveries.

If you remember only one travel principle for preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, remember this: treat the night as your most important ascent. Where you sleep is where you choose safety.

Pacing and posture—how you move becomes your oxygen strategy

It is tempting to think that acclimatization is something that happens while you do nothing. In truth, your behaviour shapes it. The way you move—your pacing, your posture, your breath—can either support your adaptation or sabotage it. In the first days, preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is as much about the style of your walking as it is about your itinerary.

The most reliable high-altitude pacing is not athletic; it is rhythmic. On inclines, shorten your steps. Allow your breath to set the tempo, not your impatience. If you use trekking poles, let them steady your balance and take a little load off your legs, which reduces unnecessary strain. When you feel your heart racing, pause briefly. Not a long break that cools you down, but a small pause—a few breaths—to keep effort smooth. This “micro-rest” habit is remarkably effective at altitude, and it is discreet enough that it does not change the elegance of your day.

Posture matters because shallow breathing is common when people are tense or excited. Lift your chest gently, relax your shoulders, and let your breathing deepen. You do not need to force it. You simply need to stop constricting it. Many travellers, particularly those who arrive after long flights, carry tension in the ribcage. Releasing that tension supports the body’s natural response to thin air. This is a practical, almost invisible form of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh.

A good pacing strategy also includes humility with hills around Leh. Those hills look small from a balcony; they can feel punishing on Day 2. Choose routes that allow you to stop easily. If you are exploring a monastery complex, take your time on stairs. Let the visit be slow and attentive rather than brisk and breathless. The goal is not to prove you can handle altitude; the goal is to adapt to it so you can enjoy Ladakh’s higher routes later.

Think of your movement as a conversation with the landscape. Ladakh replies to those who speak softly. When you pace yourself well, you are not merely preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh—you are learning how to inhabit the place with grace.

Eating, drinking, and sleeping—your quiet medicine

Hydration in a high desert (how dehydration disguises itself as AMS)

Ladakh is not only high; it is dry. The air can drink you faster than you realise. And dehydration has a sly talent for mimicking altitude symptoms: headache, fatigue, dizziness, nausea. This is why hydration is central to preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, and why it must be handled with a little more seriousness than “drink when thirsty.”

In the first days, drink regularly throughout the day. Not to the point of discomfort, but with steady intention. Warm fluids can be easier than cold water when your appetite and stomach are uncertain. Consider adding electrolytes, especially if you are sweating during walks or if you have diarrhoea from travel changes. The goal is not to turn your day into a laboratory. The goal is to reduce avoidable stress on the body while it is adjusting to high altitude travel.

A practical cue is simple: check your urine colour. Dark and concentrated often means you need more fluids. Another cue is the feeling of dryness in your mouth and lips, especially overnight. Many travellers wake with a dry throat; this is common, but it is also a sign to hydrate well in the evening and morning. When you are well hydrated, mild headaches often soften. When you are dehydrated, headaches often sharpen, and you may mistake that sharpening for worsening altitude sickness in Ladakh.

Hydration also supports sleep, and sleep supports acclimatization. Everything in the first days is connected. When travellers fail to hydrate, they often sleep poorly, then feel worse, then push harder out of frustration. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is partly a matter of breaking this cycle before it begins.

If you want the most European of pleasures at altitude, make hydration feel civilised. A pot of tea, a warm broth, a pause in the sun. The body responds well when care feels gentle rather than punitive. And in Ladakh’s dry high desert, steady hydration is one of the most reliable protections you can give yourself.

Warm, simple meals and the appetite that comes and goes

Appetite at altitude is a shy animal. Some travellers feel hungry and eat with delight; others find food suddenly uninteresting. Both experiences can be normal during the acclimatization process. What matters for preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is not culinary ambition, but steady nourishment.

In the first days, favour warm, simple meals. Think soups, rice, vegetables, gentle proteins, bread, and familiar flavours. Heavy, rich meals can feel oppressive when your body is already working harder than usual. If you feel slightly nauseated, smaller portions more often can be easier than one large meal. Do not try to “train” your appetite by forcing food; instead, keep intake consistent and mild.

Carbohydrates are often useful at altitude because they are efficient fuel. Many high-altitude travellers naturally crave them, and that is not a moral failing—it is physiology. Eating enough supports energy and reduces the sense of weakness that makes people anxious about altitude sickness in Ladakh. A warm breakfast can be particularly stabilising, especially if you have slept lightly.

There is also a cultural tenderness in eating simply in Ladakh. The warmth of a meal is not only nutrition; it is comfort. When you treat food as part of acclimatization—part of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh—you can choose meals that support your body without turning eating into a medical chore. The best approach is steady and unremarkable. A traveller who eats gently tends to sleep better, and a traveller who sleeps better tends to acclimatize more smoothly.

If you are travelling with a group, make meals quiet. Let people eat without pressure. Let the day feel spacious. In Ladakh, elegance is often found in small things done well: a warm meal, a slow conversation, and the patience to let your body catch up with your imagination.

Altitude sleep—why the night feels strange

Many travellers are surprised that their first nights in Leh feel slightly unsettled. Sleep can be lighter. Dreams can be vivid. You may wake more often than usual. This is not necessarily a sign of danger; it can be part of the body’s early adjustment to high altitude travel. Understanding this helps in preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, because anxiety about sleep often leads people to make poor decisions the next day—skipping meals, overusing caffeine, or pushing through fatigue.

Support your sleep with simple measures. Keep your room warm. Cold stress makes breathing feel harder and sleep more restless. Avoid strenuous activity late in the day; your heart rate may stay elevated longer at altitude, which can make falling asleep more difficult. Eat a modest dinner and hydrate, but do not go to bed with an overfull stomach. If you enjoy herbal tea, it can become a calming ritual, a signal to the body that the day is ending.

If you wake with a mild headache, drink water and rest. If the headache is severe or worsening, treat it seriously as part of your symptom monitoring for altitude sickness in Ladakh. The key is to observe without panic. Your body is adapting. It may not do so in a perfectly smooth line, but it often improves over successive nights when you respect acclimatization.

Europeans sometimes expect to “sleep well because we are tired from travel.” At altitude, tiredness does not guarantee deep sleep. The nervous system is alert, responding to thinner air. Accepting this prevents frustration. And frustration is a subtle enemy: it makes people rush their itinerary, which is precisely what undermines preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh.

When sleep feels strange, make the day gentler rather than harsher. Your holiday is not a race. Ladakh will not disappear because you rested. If anything, it becomes more available when your body is calm enough to receive it.

Treks and road trips: the two ways people get into trouble (and how to avoid it)

Trekking in Ladakh—when “fitness” doesn’t guarantee comfort

Trekking in Ladakh carries a particular temptation: the landscape is so open, so vast, that you feel you should be able to stride through it like a character in a novel. Yet altitude makes even strong bodies behave differently. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh requires you to understand that fitness is not the same as acclimatization. You can be trained and still suffer if you do not allow time for the body to adapt.

When you plan short treks, design conservative first days. Reduce walking hours at the start. Build in rest time, not as a reluctant concession but as a deliberate feature. A common error is to begin with a long first trekking day because “the route looks easy.” At altitude, what looks easy can feel exhausting, and exhaustion increases the risk of symptoms. If you want to prevent altitude sickness in Ladakh, you must treat the first trekking days as a continuation of acclimatization, not as the moment when acclimatization ends.

Keep the rhythm steady. Eat and drink even when you do not feel hungry or thirsty. Watch for small changes: a headache that intensifies with exertion, nausea that does not resolve, unusual fatigue. If symptoms appear, the correct response is usually to slow down, rest, and avoid further ascent until you are stable. This is not fear; it is competence.

Trekking also involves environmental stresses that amplify altitude: sun exposure, dry air, wind, and temperature swings. Protect your skin, cover your head, keep warm when the sun drops. These may seem like minor comfort details, but comfort reduces stress, and stress influences how your body responds to thin air. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is often the accumulation of small wise choices.

If you are travelling with a guide, trust their pacing suggestions. Guides who have spent seasons in Ladakh often have an instinct for what “too fast” looks like. And if you are self-guiding, practice humility: choose routes that allow you to retreat, and do not treat the day’s plan as sacred. Ladakh rewards flexibility. Your best trek is the one you can enjoy without your body struggling for air.

Road trips—fast altitude gain disguised as comfort

Road travel in Ladakh can feel deceptively easy. You are seated. You are protected from wind. You watch the landscape rise around you as if you are in a theatre. Yet road trips are one of the most common triggers of altitude sickness in Ladakh because they allow rapid altitude gain without physical warning. Your legs do not complain, so you assume you are fine. Meanwhile, your body is being asked to adapt faster than it can.

The safest road-trip planning relies on the same principle as safe trekking: conservative sleeping altitude, gradual ascent, and honest symptom monitoring. If you have just arrived, avoid itineraries that place you at very high sleeping altitudes on the first nights. Day trips are a better early choice: visit higher places briefly, then return to sleep lower. This approach is not only safer, it is more enjoyable. You arrive at your destination with steadier breath and a calmer mind.

Another practical measure is pacing your day even when driving. Stop often. Walk gently rather than rushing for photographs. Drink water. Eat small snacks. And if anyone in the vehicle develops a worsening headache or nausea, do not brush it off as carsickness. Treat it as a possible altitude symptom. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is much easier than managing it once it escalates, and road travel can escalate it quickly if you ignore early signs.

There is also a psychological factor: people are reluctant to change a road itinerary because it feels like admitting defeat. But in Ladakh, changing plans is often the most sensible and elegant decision. A delayed lake visit is not a tragedy. A compromised health day is. The landscape will remain; your wellbeing is the more fragile asset. When you choose flexibility, you protect the entire journey.

Think of road trips as altitude exposure, not simply transportation. When you treat them with respect, they become one of the most beautiful ways to see Ladakh without risk. That is the heart of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh: enjoying more by forcing less.

Medications, oxygen, and “just in case” tools (with clear boundaries)

Travellers often ask for a tidy solution: a pill, a device, a shortcut. It is understandable. Altitude feels abstract until it touches your body. Yet the most reliable method for preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh remains acclimatization—time, pacing, and conservative sleeping altitude. Medications and tools can play a supporting role, but they are not permissions to ignore the basics.

A commonly discussed medication is acetazolamide (often known by a brand name). Some travellers use it preventively or therapeutically for acute mountain sickness. Because dosing and suitability vary with individual medical history, it is sensible to discuss it with a clinician before travel. The same is true for any plan involving medication at altitude. If you have pre-existing conditions, or if you are unsure, professional advice is part of good preparation.

Supplemental oxygen can relieve symptoms and provide comfort, especially in a clinical or emergency context. In some places it is available in hotels or clinics. But oxygen should not be used as a way to continue ascending while symptoms worsen. If symptoms are severe or escalating, descending remains the key response. This is the boundary that experienced travellers respect: relief is not the same as resolution.

“Just in case” tools also include the simplest ones: a thermometer, a pulse oximeter, a list of emergency contacts, and a plan for what you will do if someone becomes unwell. These are not romantic items, but they reduce panic because they replace uncertainty with a clear next step. Panic often leads to poor decisions; clarity supports preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh because it encourages early action rather than denial.

If you remember one practical frame, let it be this: tools can support a conservative itinerary, but they cannot replace it. The most sophisticated safety device in Ladakh is still a willingness to rest, to delay, to descend if necessary, and to treat your body as the primary traveller.

A small field guide to symptoms (reader-friendly, not clinical)

A field guide should not frighten you. It should steady you. The goal is to notice patterns early, so preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh remains prevention rather than rescue. Start with morning honesty. When you wake, ask yourself: How is my head? How is my appetite? How is my breath at rest? Do I feel steady when I stand? These are simple questions, and they are often enough.

Mild symptoms that improve with water, rest, and a gentle day can be part of the normal acclimatization process. A light headache that softens after breakfast and hydration, a slightly restless night that becomes calmer on the second and third nights—these are common. But symptoms that intensify, especially with exertion, deserve caution. If a headache worsens through the day, if nausea becomes vomiting, if you feel unusually weak, or if you become short of breath while resting, treat this as a reason to stop ascending and reassess.

The most dangerous situations often involve people who feel pressured to continue. Pressure can be internal—“I don’t want to waste time”—or social—“everyone else is fine.” Remove that pressure in advance. Tell yourself that the itinerary is flexible. Tell your companions that health is not negotiable. This cultural agreement is part of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, because it makes it easier to do the right thing when the moment arrives.

If you need a simple decision rule, use three steps. First, stop and rest. Second, hydrate and eat something light. Third, reassess after a period of calm. If you improve, continue gently at the same sleeping altitude. If you worsen, do not ascend. If you are severe or confused, descend and seek medical help. It is not dramatic; it is wise. And it allows you to continue loving the journey rather than fighting it.

A traveller who understands symptoms is not anxious; they are prepared. Preparedness at altitude is not pessimism. It is the quiet confidence of someone who knows how to care for themselves in a beautiful, demanding landscape.

FAQ

FAQ: The questions travellers ask most often, answered calmly

Q: How many days should I acclimatize in Leh?

A: For many travellers, two to three nights in Leh with gentle days is a solid start. If you can spare four or five days, preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes easier because your body has more time to adjust before higher routes and longer drives.

Q: Is it normal to sleep badly on the first night?

A: Yes, light or restless sleep can be common in the first nights of high altitude travel. Support sleep with warmth, hydration, and a calm evening routine. If severe symptoms appear, reassess your plan rather than forcing onward.

Q: Can I do a day trip to a higher place early on?

A: Often, yes—if you feel well and you return to sleep lower. This “climb high, sleep low” approach is a classic part of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh. Keep the day gentle, hydrate, and treat any worsening headache or nausea as a reason to stop ascending.

Q: What should I do if I get a headache in Leh?

A: First, rest and hydrate, and eat something light. Keep exertion low. If the headache improves, continue gently at the same sleeping altitude. If it worsens, or if you have vomiting, confusion, or breathlessness at rest, seek medical help and consider descending.

Q: Does being fit protect me from altitude sickness in Ladakh?

A: Fitness helps with effort, but it does not replace acclimatization. Many fit travellers still develop symptoms if they ascend too quickly or sleep too high too soon. Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is primarily about pacing, sleep altitude, and time.

Q: Should I take medication to prevent altitude sickness?

A: Some travellers use medications such as acetazolamide, but suitability and dosing depend on individual health factors. The safest approach is to discuss this with a clinician before travel. Even with medication, a gradual itinerary remains essential.

FAQ: A few practical habits that quietly reduce risk

Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is rarely about a single dramatic decision. It is about habits that keep your body’s workload manageable while it adapts. Hydrate steadily in the dry high desert climate. Eat simple, warm meals, especially in the first days when appetite may be inconsistent. Keep your pace gentle on inclines, using short steps and small pauses. Avoid alcohol early on, because it disrupts sleep and hydration and makes symptoms harder to interpret.

Plan your first nights conservatively. In Ladakh, the most practical safety tool is a sensible sleeping altitude. Use day trips for higher views while returning to a lower base. If you feel unwell, do not treat it as a personal failure. Treat it as information. Rest, reassess, and adjust. This calm responsiveness is the most reliable form of preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh, and it allows the trip to stay pleasurable rather than anxious.

Finally, build margin into your itinerary. Europeans often travel with limited holiday time, but a buffer day is not wasted. It protects you from weather changes, road delays, and the unpredictable pace of acclimatization. In practice, margin is what turns a strict plan into a graceful journey.

Conclusion—how Ladakh rewards the patient body

The clearest takeaways, without turning your trip into a rulebook

If you want a conclusion you can remember without effort, it is this: preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is the art of arriving slowly. Your first days in Leh are not an obstacle to the trip; they are the beginning of the trip. When you rest early, hydrate steadily, eat simply, and sleep conservatively, you give your body the time it needs to adapt. In return, the landscape opens with less strain and more pleasure.

Keep the principle of sleep altitude close. Visit higher places during the day if you are stable, but return to a safer sleeping altitude early on. Treat road trips as altitude exposure, not just transportation. On treks, pace yourself as if you are composing a line of music—steady, breathable, and unforced. Watch symptoms with calm honesty. Mild discomfort can be normal, but worsening symptoms demand respect and often a change of plan.

These are not complicated instructions. They are simply the habits of travellers who wish to enjoy Ladakh fully. A rushed itinerary often creates a fragile holiday. A gradual itinerary creates a resilient one. And resilience, in the end, is what makes a journey feel generous rather than exhausting.

Ladakh-specific wisdom—how locals and landscapes teach restraint

There is a quality in Ladakh that Europeans often recognise instinctively: a kind of dignity in moving at the right pace. The villages do not look hurried. The monasteries do not feel impatient. Even the silence has a rhythm. When you follow that rhythm, preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh becomes almost a side effect of living more gently for a few days.

This is not sentimental. It is practical. A traveller who slows down notices more and suffers less. They drink water not because an app told them to, but because the dry air makes it sensible. They rest not because they are weak, but because resting makes the next day better. They change plans without drama, because they understand that the landscape is not going anywhere. The luxury in Ladakh is not speed. It is margin.

And so the final note is simple: let your first breaths in Leh be unhurried. Let the trip begin with ease. If you treat acclimatization as part of the beauty, Ladakh will reward you—not only with views, but with the calm, steady feeling of a body that has learned to belong in thin air.

Final note: Preventing altitude sickness in Ladakh is not about making the journey smaller. It is about giving it enough time to become spacious—so that when you look out over the high desert light, you are not merely enduring the altitude, you are living it.

About the Author

Sidonie Morel is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.