When Ladakh Began to Count Its Own Centuries

By Declan P. O’Connor

Lead: A Timeline Written in Stone, Ink, and Treaties

Why a year-by-year spine matters in a place where memory travels faster than paper

To write a Ladakh history timeline with any honesty, you begin by admitting what the landscape does to certainty. Valleys compress distance; winters compress time. A journey that looks brief on a map becomes a slow argument with altitude, weather, and the availability of passable ground. That is why the Ladakh history timeline is best told not as a parade of “great men” or a catalogue of monasteries, but as a sequence of turning points—moments when authority, trade, and borders changed enough that people felt it in their daily decisions. If you are a European reader used to tidy timelines, Ladakh resists that tidiness. Its history often arrives as fragments: an inscription here, a chronicle entry there, a treaty clause that quietly redraws what “belongs” to whom.

So the ambition of this Ladakh history timeline is practical: to anchor the story in dates that can be tied to evidence—material traces, recorded events, known dynastic shifts, and documented legal acts. When the sources go thin, the narrative will not pretend otherwise. In a region so often romanticised, restraint is not a lack of imagination; it is a form of respect. The Ladakh history timeline, properly handled, shows how a small kingdom survived by bargaining with larger powers, how a borderland learned to speak the language of treaties, and how the twentieth and twenty-first centuries turned old caravan routes into strategic corridors.

What follows is a narrative spine, not a museum label. It moves through the eras that still shape Ladakh’s political reality and cultural confidence: early traces before kingdoms had paper, the emergence of coherent rule, the consolidation under the Namgyal line, the shock of conquest and the paperwork that followed, and the modern legal reorganisation that made Ladakh a Union Territory. Along the way, this Ladakh history timeline keeps returning to the same question: when did power change hands in ways that ordinary people could not ignore?

What counts as a “date” here—and what does not

In any Ladakh history timeline, “dated” does not always mean “precisely measured.” Some eras are anchored by firm markers—treaties, wars recorded by multiple parties, administrative acts printed and enforced. Other eras rely on chronicles and later compilations that preserve an older memory but also reflect the politics of whoever wrote them down. The point is not to flatten every kind of evidence into one standard. The point is to tell you, as clearly as possible, what kind of evidence supports each stretch of the Ladakh history timeline.

Three categories matter most. First, material traces: rock art, inscriptions, fort ruins, and the physical infrastructure of rule. These can show presence and activity, but they rarely give you a clean calendar date without specialist study. Second, narrative texts: chronicles and travel accounts that attempt to order the past into a story, often with dynastic legitimacy in mind. These can be invaluable, but they must be treated as sources with a viewpoint. Third, documentary turning points: treaties and legal acts that define relationships between polities and reshape governance. In the Ladakh history timeline, these documentary hinges often matter more than battles, because they describe what the victors and survivors agreed to live with.

In Ladakh, the past is not “behind” you. It is layered beneath your feet—stone under dust under snow—waiting for the brief season when it can be read.

This is why the Ladakh history timeline will sometimes slow down at a treaty and move quickly through a century: the treaty is a surviving piece of language that changed reality. It is also why certain seductive phrases and easy myths are left out. Not because Ladakh lacks grandeur, but because grandeur is too often used as a shortcut around evidence. The aim here is a Ladakh history timeline that is vivid without becoming careless.

Timeline: Before Kingdoms Had Paper (Prehistoric–Early Historic)

Rock art corridors and the oldest habit of passage

The earliest stretch of a Ladakh history timeline is the hardest to “date” in the way modern readers expect, and it is also the easiest to sensationalise. Resist the temptation. What can be said with confidence is simpler and, in its own way, more profound: Ladakh preserves extensive rock art—petroglyphs and carved panels—along routes that make sense as corridors of movement. In other words, long before the region was governed by a named dynasty, people moved through these valleys, paused long enough to mark stone, and left traces that later centuries could not entirely erase.

For a Ladakh history timeline, the practical implication is that the region’s story begins as movement, not as statehood. The Indus valley and its tributaries did not wait for a king to become meaningful. They were already meaningful because they connected worlds: plateau to plain, pasture to settlement, high routes to lower markets. Rock art suggests not a single “origin” but repeated use—an argument, carved into stone, that Ladakh was never truly isolated. That matters when you later read about treaties and borders: the impulse to connect is older than the impulse to rule.

What you should not do in a responsible Ladakh history timeline is pin precise centuries onto rock art without citing specialist dating work. The panels themselves can be described—animals, hunters, symbols, sometimes script-like marks—but the calendar needs scholarship. The honest posture is to treat this era as the deep foundation: evidence of human presence and passage, preceding the first coherent political labels that appear in written sources. In a region where winter can silence even the present, these carvings remind you that the oldest chapter of the Ladakh history timeline is not a tale of rulers. It is a tale of routes.

From traces to early legibility: the first steps toward recorded history

To move from “presence” to “history” in a Ladakh history timeline, you need legibility: marks that can be tied to languages, institutions, or external references. This is where inscriptions, early fortifications, and the growth of religious networks begin to matter. Not because religion is a decorative feature of the Himalaya, but because monasteries and their patrons often produced the durable records that states relied upon. Where trade creates wealth and monasteries create literacy, the Ladakh history timeline begins to gain dates, names, and claims.

Even here, caution is the discipline that keeps the story true. Early historic references to Ladakh and adjacent regions often appear in the context of larger Tibetan and Central Asian worlds. This does not mean Ladakh was merely a passive frontier. It means that the earliest written visibility of Ladakh is frequently mediated—seen through the concerns of wider polities and travellers. The Ladakh history timeline, at this stage, is a developing silhouette: a region becoming visible as it becomes connected to institutions that record, tax, negotiate, and defend.

For the reader, the important practical lesson is that early Ladakh should not be treated as a blank space awaiting “discovery.” It was already inhabited, traversed, and culturally active. The lack of a neat early calendar is not proof of emptiness; it is proof of the limitations of surviving documentation. A careful Ladakh history timeline therefore keeps two thoughts together: the region’s deep antiquity is supported by material traces, while the region’s early political narrative becomes clearer only as written sources and institutional records thicken. That is the threshold we now cross.

c. 950–1600: Maryul and the Slow Emergence of a Kingdom

c. 950 and the West Tibetan frame: how “Maryul” enters the story

Many Ladakh history timeline accounts begin around the tenth century because this is when coherent political naming becomes easier to track in the scholarly record: the appearance of “Maryul” as a kingdom associated with the broader West Tibetan sphere. The term matters because it suggests not just geography but an attempt to govern geography. In a landscape where a valley can be an entire world, naming a kingdom is a claim that multiple valleys can be held together under a single political imagination.

In the Ladakh history timeline, c. 950 functions less like a single dramatic year and more like a threshold. It marks the period when Ladakh’s political life is increasingly discussed in relation to West Tibetan lineages and their successors. This does not mean the region suddenly sprang into existence. It means that the surviving narrative and documentary threads—what scholars can reconstruct with care—begin to form a more continuous chain. Forts, routes, and religious centres become part of a recognisable pattern of rule.

For a European reader, it may help to think of this as the Himalayan version of early medieval state formation: power expressed through control of passes, taxation of trade, patronage of religious institutions, and the ability to keep rival elites from splitting the territory into permanent fragments. The Ladakh history timeline here is not a story of constant war; it is a story of constant negotiation with terrain. And that negotiation, over centuries, produces something durable enough to be remembered as a kingdom. In the decades and centuries that follow, names change, alliances shift, but the underlying challenge remains the same: how do you make authority travel in a place where travel itself is never guaranteed?

1100s–1500s: valleys as political units, monasteries as institutions, trade as leverage

Between the early medieval threshold and the later consolidation of dynastic power, the Ladakh history timeline is shaped by three quiet forces: the political significance of valleys, the institutional strength of monasteries, and the economic leverage of trade. Valleys matter because they define settlement patterns and agricultural possibility. Monasteries matter because they stabilise learning, ritual authority, and networks of patronage. Trade matters because Ladakh sits where multiple worlds touch, and whoever can tax, protect, or redirect caravans gains resources that can be turned into rule.

This is also the period when Ladakh’s story is most easily distorted into a romantic “mystical” narrative. A more practical view is better: monasteries were not just spiritual refuges; they were durable institutions that could store wealth, sponsor art and scholarship, and mediate local disputes. In a Ladakh history timeline, these functions matter because they help explain continuity. Kingdoms survive not merely through armies but through the institutions that make a kingdom worth keeping together.

Trade, meanwhile, is the thread that runs through the Ladakh history timeline like a persistent melody. Even when the names of rulers are uncertain, the logic of the region is clear: Ladakh is valuable because it connects. Caravans and traders do not care about romance; they care about routes, security, and predictable tolls. That economic reality shapes political reality. When you later encounter treaties and wars, remember that they often revolve around the control of movement—who can pass, who can profit, who can claim the right to regulate. By the time we reach the period of stronger dynastic consolidation, Ladakh’s political life has already been rehearsed for centuries in the practical theatre of valley governance and trade management. The Ladakh history timeline is gaining pace, but it is still written in slow ink.

1470–1684: Consolidation Under the Namgyal Line and the Cost of Visibility

c. 1470s–1600: consolidation as a craft, not a slogan

The Namgyal period occupies a central place in any Ladakh history timeline because it represents consolidation—rule that becomes more legible in records, more visible in architecture, and more defensible in memory. Consolidation in Ladakh is not a simple matter of conquest. It is a craft: balancing local elites, sustaining monastic patronage, managing trade revenues, and projecting authority across difficult terrain. This is the period when the kingdom’s identity becomes clearer, not only to outsiders but to itself.

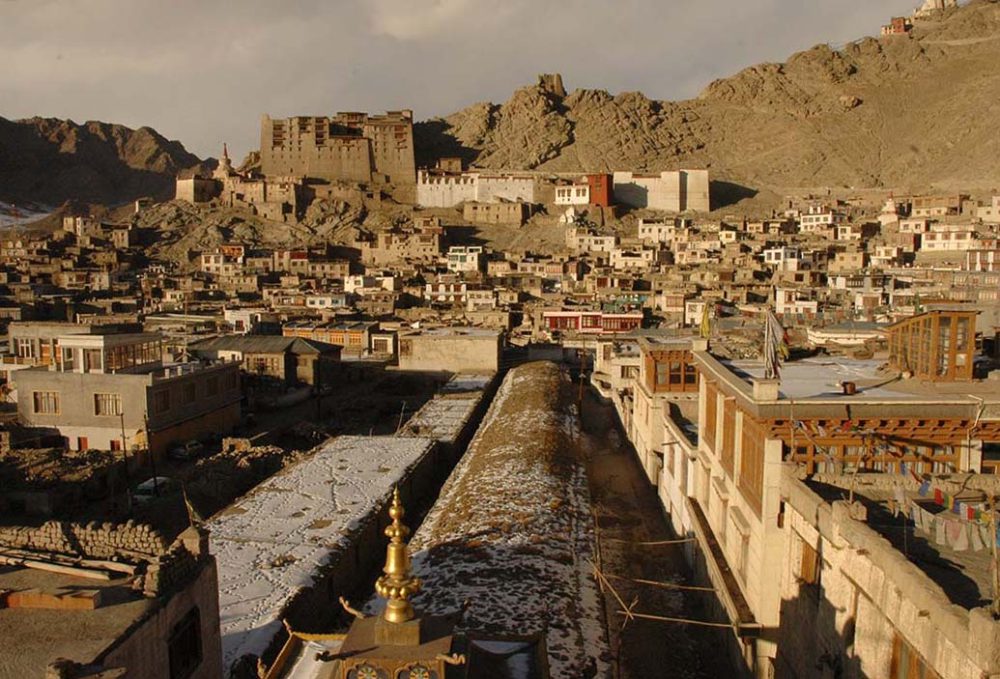

Leh’s rise as a political centre is part of that story, and architecture becomes a kind of evidence: palaces and fortifications are not merely scenic; they are statements of governance. In a Ladakh history timeline, such statements matter because they imply administrative capacity—storage, taxation, protection, and the ability to host diplomacy. A palace is not only a residence; it is a machine that turns resources into authority. When later centuries speak of Ladakh as a kingdom, this is one reason: the kingdom left behind visible infrastructure that outlasted individual rulers.

Yet visibility has a cost. As Ladakh becomes more coherent, it also becomes more legible to larger neighbours and empires. A small polity that sits quietly may be ignored; a polity that successfully taxes trade and builds durable institutions becomes worth contesting. In the Ladakh history timeline, consolidation is therefore both an achievement and an invitation. It sharpens the kingdom’s internal confidence while drawing external attention. By the seventeenth century, that attention becomes dangerous.

1679–1684: war, diplomacy, and the Treaty of Tingmosgang as a hinge

The years 1679 to 1684 are a dramatic hinge in the Ladakh history timeline because they show what happens when a borderland kingdom is forced to negotiate with powers that can mobilise resources on a different scale. The conflict often described as the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal war culminates in a settlement associated with 1684 and the Treaty of Tingmosgang. For a timeline, the key point is not to exaggerate what the surviving evidence can guarantee. Some details survive through chronicles and later summaries; the treaty’s full original text is not preserved as a clean modern reader’s document. The Ladakh history timeline must therefore present 1684 as a turning point while remaining transparent about the evidentiary structure.

Still, even a partially preserved settlement matters because it indicates a recalibration of relations: trade, tribute, and boundaries of influence were at stake. The seventeenth century is when Ladakh’s location—between Tibetan worlds and South Asian empires—stops being merely advantageous and becomes existential. The kingdom’s survival requires diplomacy that is not optional, and warfare that is not entirely avoidable. The Ladakh history timeline here reads like a lesson: a small state can endure if it knows when to fight and when to sign.

For the reader, the practical significance of 1684 is that it foreshadows the later treaty logic of the region. When you reach the nineteenth-century documentary turning points, you are not seeing something wholly new. You are seeing an older pattern harden into paperwork. In a Ladakh history timeline, 1684 is the first major signal that external pressures will increasingly define internal possibilities. The kingdom survives the century, but it does so by accepting constraints—constraints that will tighten again in the nineteenth century with far less room to manoeuvre.

1834–1842: Conquest, War, and the Paper That Ends a Kingdom

1834: the Dogra campaign begins, and Ladakh’s sovereignty starts to narrow

Few entries in a Ladakh history timeline carry the clarity and consequence of 1834. This is when the Dogra campaign into Ladakh begins—an expansion associated with the Jammu-based power rising under the broader Sikh imperial framework of the period. For Ladakh, 1834 marks the start of a process that would end the kingdom’s sovereignty. It is not simply a military episode; it is the beginning of administrative absorption, the replacement of a local dynastic logic with a system that answers elsewhere.

In a Ladakh history timeline, the shift after 1834 can be felt in the nature of decisions: from choices shaped by Ladakh’s own elite bargains to choices shaped by external strategic aims. Ladakh’s wealth—particularly what could be extracted through trade and taxation—becomes part of a larger fiscal and political calculus. The kingdom’s ability to negotiate as an equal diminishes. Even if local life continues, the framework around local life changes.

It is tempting, when writing about conquest, to turn the narrative into a morality play. The more practical approach is to focus on consequences. After 1834, Ladakh’s political future is increasingly decided through campaigns, diplomatic messages, and the kind of formal agreements that empires prefer. That preference matters. Empires do not merely conquer; they document. And documentation, in the Ladakh history timeline, is often the point at which history becomes irreversible. The years ahead will prove that. They will also show that Ladakh’s position between larger powers makes it a stage not only for conquest but for internationalised frontier conflict.

1841–1842: conflict with Tibet and the 1842 settlement as a documentary hinge

The conflict of 1841–1842, often framed as the Dogra–Tibetan war, culminates in a settlement associated with Chushul in 1842. In a Ladakh history timeline, this is one of the most important documentary hinges because it ties warfare to written commitments. The settlement’s translated clauses, as preserved in later publications, emphasise non-interference and the continuation of established relations. The exact phrasing matters less here than the fact that the region’s political reality is being stated in a language that assumes borders and obligations—language that would increasingly dominate frontier politics.

For Ladakh, the 1842 settlement does not restore a lost kingdom. It confirms a new order after the shock of conflict. The Ladakh history timeline therefore treats 1842 not as a neat closure but as a pivot into a new era: Ladakh becomes part of the Jammu and Kashmir polity under Dogra rule, and its external relations are reframed through that larger structure. The “end of a kingdom” is not a single day; it is a transition made official by conquest and stabilised by agreement.

For a European reader, 1842 offers a familiar lesson about modernity: states increasingly define themselves through documents. In the Ladakh history timeline, treaties are not ornamental. They are tools that carve a frontier into language. Once a frontier is written down, it becomes something armies and bureaucracies can argue over for generations. That is why the nineteenth century is not simply a period of “foreign rule.” It is the period when the region’s political vocabulary shifts toward legal commitments that will echo into the twentieth century and beyond.

1843–2018: Administration, Partition, and the Twentieth Century’s New Frontiers

1843–1946: being governed, being surveyed, being described—Ladakh becomes legible to the modern state

After the mid-nineteenth-century turning point, the Ladakh history timeline changes in texture. The story is less about dynastic succession and more about administration: revenue systems, governance structures, and the increasing production of descriptions—gazetteers, surveys, and reports—that render Ladakh “legible” to a modernising state. This is not merely an intellectual change. Legibility affects what roads are built, what taxes are imposed, what disputes are recorded, and how local institutions negotiate their space.

The practical consequence for Ladakh is a reorientation. Local life does not vanish; monasteries continue, trade continues in altered forms, and communities adapt. But the framework of authority sits more firmly outside the region’s traditional dynastic narrative. The Ladakh history timeline in this period is therefore the story of adaptation under a larger polity: Ladakh is governed as part of Jammu and Kashmir, while also retaining cultural and religious distinctiveness that does not neatly fit the administrative categories of distant capitals.

For the reader, this era is a reminder that governance can be quieter than conquest and yet just as transformative. When states describe a place in official language, they also define what counts as a “problem” and what counts as a “resource.” The Ladakh history timeline thus becomes a record not only of events but of classifications: borders, districts, revenue categories, and political identities. By the time the subcontinent reaches the mid-twentieth century, these classifications will be tested by a rupture far larger than Ladakh itself.

1947–2018: Partition’s shadow, wars, and the slow hardening of strategic Ladakh

The year 1947 is unavoidable in a Ladakh history timeline because it marks the partition of British India and the beginning of a new geopolitical reality in which Ladakh becomes part of contested narratives. The first Indo-Pakistani war, the evolving status of Jammu and Kashmir, and the later border tensions with China reshape the region’s strategic meaning. For the people living there, “strategy” is not an abstraction. It becomes roads, military presence, administrative attention, and the sense that the frontier is not merely a line on a map but a lived condition.

In the Ladakh history timeline, the 1960s matter because border conflict between India and China makes the high Himalaya a theatre of national security concerns. Again, the point is not to reduce Ladakh to conflict. The point is to understand how conflict reorganises governance and development. Connectivity becomes both a promise and a demand: roads that were once seasonal ambitions become strategic necessities. The region’s relationship to the rest of India changes as infrastructure and policy attempt to manage a harsh geography under modern pressures.

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the Ladakh history timeline includes another transformation: the growing visibility of Ladakh in public imagination through travel, media, and political debate about governance. This visibility can bring economic opportunity and cultural exchange, but it can also flatten complexity into cliché. A careful timeline notes the growth without turning the article into a guidebook. What matters historically is that Ladakh’s identity debates—about representation, administration, and the balance between development and cultural integrity—intensify as the modern state’s presence becomes more tangible. These debates form the immediate prelude to the legal turning point of 2019.

2019–Present: Union Territory and the Administrative Rewriting of the Map

2019: legal reorganisation as a modern turning point with ancient echoes

The year 2019 stands in the Ladakh history timeline as a clear modern turning point: Ladakh is reorganised as a Union Territory. In legal terms, this is an administrative transformation, but history teaches you not to underestimate administrative language. When a region’s status changes in law, the channels of governance change: who decides budgets, how representation works, how development priorities are set, and how local identity is negotiated within national frameworks. For a place whose earlier turning points were marked by treaties and conquest, the twenty-first century delivers change through legislation.

In the Ladakh history timeline, it is worth noticing the echo: the shift from dynastic rule to Dogra administration in the nineteenth century was stabilised by documentary settlement; the shift to Union Territory status in 2019 is likewise stabilised by legal documentation. The instruments differ, but the pattern is recognisable. Ladakh repeatedly experiences decisive change when the language of governance changes—when authority is restated in a form that can be implemented across distance.

For European readers accustomed to the idea that modernity is an escape from old frontiers, Ladakh offers a different lesson: modernity can intensify the frontier. Administrative change coincides with ongoing geopolitical tensions and development debates that are not resolved by a new status label. The Ladakh history timeline after 2019 is still being written, and a responsible account does not pretend to predict its final shape. What can be said is that 2019 formalises a new chapter in which Ladakh’s relationship to the Indian state is redefined, and in which local arguments about identity, environment, and governance become more publicly urgent.

The 2020s: governance, connectivity, and the question of what “progress” costs at altitude

After 2019, the Ladakh history timeline becomes less about the drama of a single legal act and more about the lived consequences of being governed under a new structure. Connectivity remains central: roads, communications, and services that are presented as development also function as strategic infrastructure in a frontier region. The practical question—asked quietly in many Ladakhi households—is how to accept improvement without surrendering control over pace, place, and meaning. This question is not sentimental. In a high-altitude environment, rapid change can carry environmental costs and cultural strains that do not appear in policy summaries.

For the timeline writer, the discipline is to distinguish between dates and trends. The Ladakh history timeline can mark 2019 cleanly; it can note subsequent developments when they are tied to documented events and decisions. But it should not collapse the decade into a single narrative of triumph or disaster. Ladakh has endured by balancing: balancing trade and isolation, diplomacy and defence, local autonomy and external pressure. The 2020s ask for a new balance between development ambitions and environmental limits, between national frameworks and local sensibilities.

If this sounds abstract, remember the deeper arc of the Ladakh history timeline. The oldest chapter is movement across terrain; the medieval chapter is the formation of rule across valleys; the early modern chapter is survival between empires; the nineteenth century is conquest and documentation; the twentieth century is frontier geopolitics; the twenty-first century is administrative redefinition under continuing strategic attention. The shape changes, but the underlying reality remains: Ladakh is a place where geography forces politics to be practical. History here is not merely a memory of what happened. It is a training in how to live with limits and still remain open to the world.

FAQ and Takeaways

FAQ: sources, dates, and what this Ladakh history timeline can responsibly claim

Q: Why does the early part of the Ladakh history timeline avoid exact centuries for rock art?

A: Because rock art can demonstrate early human activity and movement, but precise calendar dating depends on specialist studies and methods. Without citing those studies, assigning exact centuries would be speculation. A reliable Ladakh history timeline distinguishes “evidence of presence” from “precisely dated events.”

Q: What makes 1684 a turning point in the Ladakh history timeline?

A: 1684 is associated with the Treaty of Tingmosgang following seventeenth-century conflict involving Ladakh, Tibet, and Mughal-linked forces. Even when the surviving evidence comes through summaries rather than a complete modern treaty text, the settlement marks a recalibration of power and trade relations—an early documentary hinge in the Ladakh history timeline.

Q: Why is 1842 treated as documentary “closure” for the kingdom?

A: Because the 1841–1842 conflict culminates in a settlement associated with Chushul in 1842, and its preserved clauses articulate non-interference and continuity of relations. In a Ladakh history timeline, such documentary outcomes matter because they stabilise a new order after conquest and embed it in agreed language.

Q: What is the single clean modern date in this Ladakh history timeline?

A: 2019. Ladakh’s reorganisation as a Union Territory is a legal act with a clear public record and implementation. That clarity is rare in a long Ladakh history timeline, which is why 2019 functions as a modern hinge comparable—in documentary force, not in moral meaning—to earlier treaty moments.

FAQ: reading the timeline without turning it into romance or propaganda

Q: Is the Ladakh history timeline mainly a story of monasteries and spirituality?

A: Monasteries are essential institutions in Ladakh’s history, but they are not the whole story. They also functioned as centres of learning, patronage, and social stability. A grounded Ladakh history timeline treats them as institutions that shaped governance and identity, not as scenery.

Q: Does the Ladakh history timeline reduce the region to war and borders?

A: It should not. Borders and wars appear because they change governance and daily life, especially after 1947. But a careful Ladakh history timeline also tracks slower forces: trade, administration, infrastructure, and local debates about identity and development.

Q: What should a reader remember after finishing this Ladakh history timeline?

A: Three ideas. First, Ladakh’s oldest story is movement through terrain. Second, Ladakh’s kingdom era survives by negotiation between stronger neighbours. Third, modern Ladakh is repeatedly reshaped by documents—treaties and legal acts—that translate geography into governance.

Conclusion: clear takeaways—and a closing note for readers who want history without illusion

A Ladakh history timeline is most convincing when it refuses to be flattering. The region does not need myth to be remarkable. Its reality is already sharper than romance: a place where movement is older than rule, where rule is shaped by valleys, and where survival often depends on choosing the least damaging compromise. The first takeaway is therefore methodological but also moral: when evidence is thin, admit it. In a Ladakh history timeline, honesty about uncertainty is not a weakness; it is the only way the later certainties—1834, 1842, 1947, 2019—can carry their rightful weight.

The second takeaway is historical: the most decisive turning points are often documentary. The Treaty of Tingmosgang in 1684, the settlement associated with Chushul in 1842, and the legal reorganisation in 2019 are not merely bureaucratic details. They are moments when power rewrote the conditions of life in language durable enough to travel across distance. The Ladakh history timeline shows that, in frontier regions, paper can be as consequential as armies. It can also be more enduring.

The third takeaway is human: Ladakh’s continuity comes from adaptation. Dynasties end, administrative structures change, external pressures rise and fall, yet communities persist by learning what the terrain allows and what politics demands. If there is a closing note worth offering to European readers, it is this: Ladakh’s history is not an escape from modern complexity; it is a masterclass in living with it. Read the Ladakh history timeline, and you see a society that has long understood a truth the lowlands often forget—progress is not merely speed. It is the art of enduring change without losing the ability to recognise yourself.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.