Why Altitude Demands a Different Kind of Traveler

By Declan P. O’Connor

Introduction — The Thin Air That Changes How We Move Through the World

Altitude Not as a Number, but as a Form of Attention

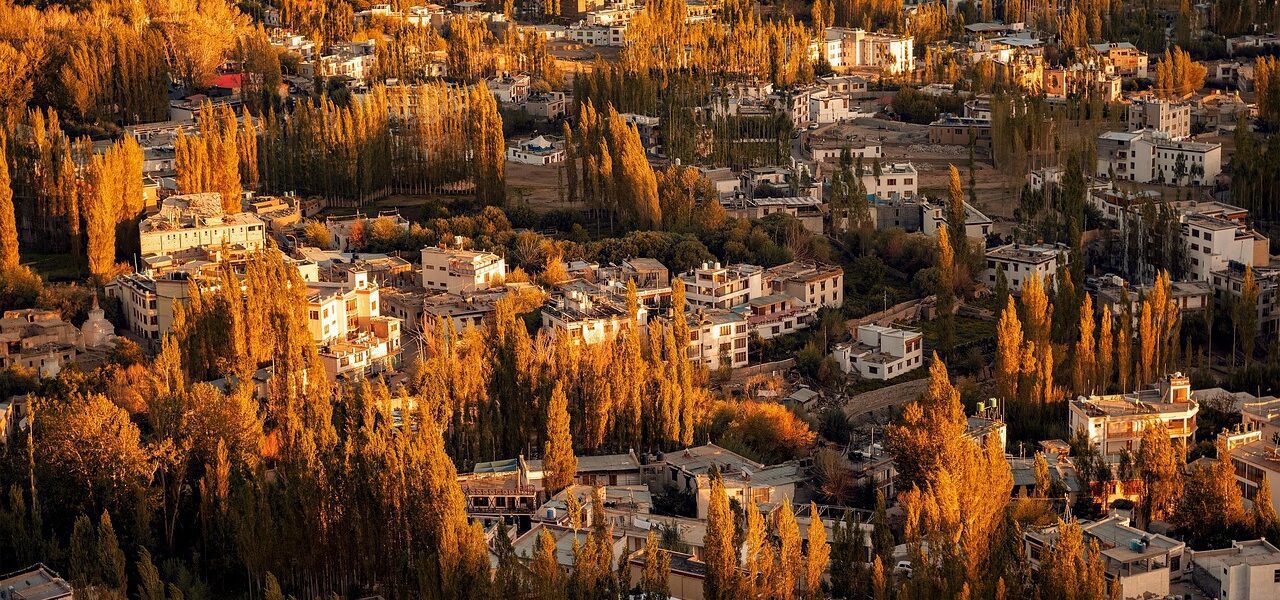

For most of us who arrive in Ladakh from Europe, altitude begins as a number on a screen. We Google “Leh elevation” on the flight, glance at 3,500 metres, and file it under “interesting fact” rather than “new grammar of reality.” We are used to distances being measured in hours, not in heartbeats. Lowland travel has trained us to believe that everything important can be scheduled, optimised, and squeezed into a long weekend. When we finally step out of the aircraft into the Ladakh sunlight, we discover something humbler and truer: the air itself has opinions about how fast we should move.

A good Ladakh altitude guide does not begin with fear, medical jargon, or worst-case scenarios. It begins with this simple confession: at high altitude, you are no longer fully in charge of time. The thin air slows your thoughts, stretches your steps, and asks you to notice the simple act of crossing a hotel courtyard. Your body, usually an obedient vehicle, becomes a negotiating partner. It insists on shorter walks, quieter evenings, and a different kind of ambition. Instead of collecting sights, you begin collecting breaths.

To acclimatize well in Ladakh is therefore not just to “manage risk,” but to accept a different rhythm of travel. You learn that going slowly is not a sign of weakness; it is the price of a deeper encounter with landscape and people. Altitude becomes less a number and more a discipline of attention: to your pulse, your thirst, your sleep, and your own impatience. This Ladakh altitude guide is, at its heart, a manual for that discipline.

What Altitude Really Does to the Body

The Physiology Behind Thin Air

The human body is remarkably democratic in the way it responds to thin air. It does not much care whether you are a trail runner from the Alps or a desk worker from Amsterdam; above a certain height, everyone is humbled. Air at Ladakh’s elevations contains roughly the same percentage of oxygen as at sea level, but the lower atmospheric pressure makes each breath deliver fewer oxygen molecules to your bloodstream. The body registers this as a kind of quiet emergency and begins to adapt. Your breathing quickens, your heart beats faster, and over time your blood chemistry changes to carry oxygen more efficiently.

A Ladakh altitude guide that reduces this process to a list of danger signs misses something essential. What is happening in those first 48 to 72 hours in Leh is not a failure of the body; it is an update. Your system is rewriting its settings for a lighter sky. That mild headache, that slightly restless sleep, that odd sense of moving through cotton wool—these are not always symptoms to panic over, but messages that you are in transition. Problems arise when we refuse to listen: when we ignore a worsening headache, push through breathlessness, or treat dizziness as an inconvenience rather than a warning.

Understanding the physiology does not require a medical degree. It requires honesty. Altitude is asking you to respect the limits of your lungs and circulation. If you accept that, acclimatization becomes less a battle and more a conversation. You give the body extra water, warmth, calories, and rest; in return, it reconfigures itself to let you walk through Ladakh’s valleys and passes with a steadier step and a clearer mind.

The Slow Traveler’s Advantage

In a culture that rewards speed, it is tempting to assume that the fittest and most efficient travelers handle altitude best. Yet the mountains stubbornly favour a different type: the slow, observant, unhurried visitor who treats each day as preparation rather than conquest. A thoughtful Ladakh altitude guide must therefore start with an uncomfortable truth for modern tourists: the less you try to “maximize” your itinerary, the safer and richer your acclimatization will be.

The slow traveler rests when the body first whispers, rather than when it finally shouts. They walk a little more slowly up the stairs, linger over breakfast, and let the afternoon drift by with a book instead of a checklist. This is not laziness; it is strategy. By keeping exertion mild in the early days, you allow your respiratory and cardiovascular systems to adjust without being pushed into crisis. Your sleep improves, your appetite stabilizes, and your energy becomes more reliable. You create the conditions for real exploration later in the trip.

There is also a moral dimension to this slowness. The impatient traveler treats Ladakh as a backdrop for their own plans. The patient traveler recognizes that the region’s altitude, climate, and communities have their own tempo, shaped by long winters and fragile water sources. To match that tempo is to show respect. When you redesign your expectations—longer stays, gentler movement, fewer daily objectives—you discover that altitude is not your enemy. It is your tutor, quietly teaching you that a good journey is not measured in the number of passes crossed, but in the quality of your attention along the way.

How to Acclimatize Safely Without Fear

The 48–72 Hour Window That Defines the Whole Trip

The first two or three days after you arrive in Leh are the foundation upon which your entire Ladakh altitude experience will rest. Think of them as the ground floor of a house: if you rush the construction, the upper levels will always feel unstable. Many itineraries fail not because of some dramatic crisis in a remote valley, but because the opening days were treated as disposable time to be “filled” rather than as sacred space for adjustment. A serious altitude guide must insist: the way you live those first 48 to 72 hours is one of the most important safety decisions you will make.

Practically, this means planning your first day as if you have far less energy than your ego expects. Check into your guesthouse, drink water slowly, eat light, familiar food, and let the day be pleasantly uneventful. Short, flat walks in the neighbourhood are fine; long uphill climbs or frantic sightseeing are not. On the second day, if you feel reasonably well, extend your range modestly: perhaps visit a monastery reachable by road, or stroll through the bazaar at a relaxed pace. If symptoms appear or worsen—severe headache, nausea, unusual breathlessness—honour them by canceling plans rather than pushing through.

What you are building in this window is not just physiological tolerance, but trust in your own judgment. By choosing rest over pride early on, you give yourself permission to make conservative decisions later, when the stakes are higher. You also signal to your companions and local guides that you take altitude seriously, which makes it easier for them to speak honestly if they see you struggling. This quiet discipline in the first days is one of the simplest, most effective forms of risk management in Ladakh.

Hydration, Breathing, and the Art of Slowing Down

It is easy to treat advice about water and breathing as banal, the stuff of every generic mountain brochure. Yet in Ladakh, where the air is dry and the sun deceptively strong, these basics become the hinges on which your acclimatization turns. A responsible Ladakh altitude guide will not simply tell you to “drink more,” but will explain how and why. At high altitude, every exhalation carries away more moisture, and your sense of thirst can lag behind your actual needs. Drinking small, regular amounts of water throughout the day helps maintain blood volume and circulation, allowing oxygen to be delivered more efficiently.

Breathing also changes. Many travelers unconsciously speed up their breathing when walking uphill, stacking shallow breaths on top of one another. This can leave you feeling anxious and exhausted. A better approach is to match your walking rhythm to deeper, more deliberate breaths—two or three steps per inhale, the same per exhale—especially on inclines. This “paced breathing” transforms steep sections from panicked rushes into slow, meditative climbs. You are not trying to overpower the slope; you are learning to cooperate with it.

Slowing down is not only physical. It is also an attitude toward stimulants and comforts. Limiting alcohol in the first days, moderating caffeine, and choosing warm, simple meals are all forms of respect for your body’s workload. Your system is already busy rewriting its rules for this new altitude; it does not need the extra puzzle of heavy drinking or erratic sleep. When you see hydration and breathing as ways of participating in that adaptation rather than just “rules to follow,” your relationship with the mountains begins to change. You move from compliance to collaboration.

Early Symptoms to Respect (Not Fear)

Nothing fills a traveler with dread quite like the phrase “altitude sickness.” Search results are full of worst-case scenarios, leaving many visitors convinced that any headache is a prelude to disaster. A more nuanced Ladakh altitude guide makes a different argument: early symptoms are not enemies, but early warning lights. They are useful precisely because they appear before serious trouble. The task is not to pretend they do not exist, nor to catastrophize them, but to interpret them honestly.

Mild headache, light dizziness when standing quickly, a slightly faster pulse, or a restless first night of sleep are all common at altitude. These sensations deserve attention but not panic. Often, they respond well to simple interventions: rest, gentle movement instead of heavy exertion, steady hydration, and, if appropriate, mild pain relief recommended by your doctor. The key is to watch trends. A headache that eases after rest is one thing; a headache that grows steadily worse, especially when combined with confusion, severe breathlessness at rest, or persistent vomiting, signals the need to descend and seek medical help.

The moral is simple: respect your body’s early distress calls. Do not try to “push through” because the group has a plan or because you have flown a long way. Ladakh will not reward that kind of stubbornness. It will reward the traveler who can say, without shame, “Today my body is asking for less.” Fear turns every twinge into a crisis; respect turns each into information. The difference between the two is often the difference between a safe, memorable journey and a miserable early exit.

Designing an Altitude-Friendly Ladakh Itinerary

The Order of Landscapes Matters

Many itineraries to Ladakh are built like shopping lists: Leh, Nubra, Pangong, maybe a high-altitude lake or a remote monastery, all strung together according to what fits into a week off from work. The problem is that altitude is not a supermarket shelf; it is a staircase. The order in which you climb that staircase shapes not only your comfort but your safety. A serious Ladakh altitude guide therefore treats the sequence of destinations as a central design question, not an afterthought.

As a broad principle, you want your itinerary to feel like a gentle ascent rather than a roller coaster. That often means spending at least two nights in Leh, then considering lower or similar-altitude excursions—perhaps to the western Sham region or nearby monasteries—before sleeping significantly higher. When you do head to places like Nubra or the high lakes, think in terms of gradual progression and sufficient nights at each level. Avoid the temptation to leap rapidly between extreme altitudes just to collect names and photographs. Your body is keeping score, even if your social media feed is not.

This ordered approach has another benefit: it opens time for real encounters. When you stop seeing Ladakh as a set of trophies to be ticked off, you begin to notice smaller things: the pattern of irrigation channels in a village, the slow rhythm of evening prayers, the way children walk to school along dusty paths. Altitude-aware itineraries are often more culturally attentive itineraries. By climbing the staircase slowly, you give both your lungs and your imagination space to work.

Why Rest Days Are Not Optional — They Are the Trip

In many travel plans, rest days are treated like the foam packaging around a fragile item: useful during transport, discarded on arrival. In Ladakh, this logic is inverted. Rest days are not the padding; they are the product. A thoughtful Ladakh altitude guide will therefore urge you to plan “empty” days that are anything but empty. These days, when you stay at the same altitude and let the body consolidate its adaptation, are precisely when some of the trip’s most memorable experiences occur.

On a rest day in Leh or a village, you might stroll slowly through markets, share tea in a courtyard, watch the light move across a monastery wall, or read on a rooftop as prayer flags shift in the wind. None of these activities demand hard exertion, yet they anchor you in the place in a way that rushed sightseeing never can. Physiologically, they allow your body to deepen its acclimatization without additional stress. Psychologically, they remind you that the purpose of travel is not constant movement but attentive presence.

It takes a certain courage to defend these quiet intervals when colleagues back home expect “highlights.” You may feel pressure to explain why you spent a full day “just” wandering in Leh rather than driving over another high pass. The answer is simple: you chose to travel well instead of merely collecting altitude statistics. You allowed rest to be central, not marginal. In doing so, you practiced a kind of hospitality toward your own limits—and discovered that Ladakh, when approached with that gentleness, has more than enough depth to fill even the slowest days.

The Psychology of High Places

What Altitude Teaches About Control and Surrender

High places have always unsettled human beings, not only because of physical danger but because they reveal how little we control. At sea level, we carry the quiet illusion that our plans, our devices, and our carefully optimised schedules are in charge. In Ladakh, that illusion thins out with the air. Weather closes a road, a headache interrupts a hike, a restless night forces a change of route. A wise Ladakh altitude guide therefore treats the psychological dimension as seriously as the physiological.

Altitude invites a kind of surrender that is not defeat, but recalibration. You discover that your worth is not measured by the number of summits you reach or passes you cross. It is measured by your willingness to listen to reality when it speaks—through your lungs, your guide, the sky. This can be difficult for travelers used to equating resilience with stubbornness. Yet true resilience often lies in the opposite direction: the ability to accept limits without resentment, to revise plans without shame, to turn back without narrating the decision as personal failure.

In the thin air above Leh, the most radical act is not to keep climbing, but to admit that you have climbed enough for today.

This surrender opens unexpected spaces. When you are no longer enslaved to the idea that you must “do it all,” you become free to notice what is actually in front of you: the sound of a river at dusk, the way an elderly villager stacks firewood, the simple relief of lying down after a long day. Altitude, then, is not only a test of lungs but a teacher of humility. It loosens our grip on control and, in the process, makes room for gratitude.

Why Ladakh Rewards the Patient Traveler

Patience is an unfashionable virtue in the age of instant booking and same-day delivery. Yet Ladakh quietly insists upon it. Roads may delay you, local festivals may rearrange your schedule, and your own body may veto an ambitious plan with a well-timed wave of exhaustion. A responsible Ladakh altitude guide does not apologise for this; it celebrates it. For it is precisely the traveler who accepts these delays with grace who receives Ladakh’s most generous gifts.

The patient traveler stays an extra night in a small village because the weather turns, and ends up sharing stories with a family around the stove. They miss one viewpoint but gain another: a long conversation with a monk in a quiet courtyard, or an unplanned walk along a side path where children play football at 3,500 metres. They discover that slowness is not merely a safety strategy but a form of intimacy with place. Altitude becomes less an obstacle to be conquered than a filter that sifts out those who are willing to wait.

This patience has ethical implications as well. It encourages you to spend more time in fewer places, to support local guesthouses and guides rather than racing through on a series of quick photo stops. Your footprint becomes lighter, your relationships deeper. The landscape remains, but your way of being in it changes. Ladakh rewards this shift not with grand spectacles, but with something quieter: the sense that, for a brief time, you have been allowed to belong.

Practical Safety Guidelines Without the Anxiety

Simple Rules That Keep You Safe

There is a temptation, when writing about high altitude, to smother readers in rules and acronyms until their enthusiasm is replaced by anxiety. A more helpful Ladakh altitude guide focuses instead on a handful of simple, memorable principles. If you follow these, the mountains will usually meet you halfway. First: ascend gradually whenever possible, adding sleeping altitude in manageable steps. Second: protect your early days as carefully as you protect your passport. Third: rest if symptoms worsen; do not negotiate with a deteriorating condition.

Fourth: communicate honestly with your companions and guides. If you are struggling, say so early, not when you are already at your limit on a remote trail. Fifth: keep yourself warm and nourished. Cold and exhaustion make every altitude symptom harder to bear. And finally: remember that “climb high, sleep low” is a helpful idea in some trekking contexts, but not a magical charm. Do not interpret it as a license to spend long, exhausting days at extreme heights simply because you plan to drop down at night. The body still keeps a tally of exertion.

These rules are not complicated, but their simplicity can be disarming. We would prefer some dramatic piece of equipment or specialized training. Instead, we are given habits: how we walk, how we rest, how we talk to each other about our limits. The good news is that these habits are within reach of any traveler willing to trade a little pride for a great deal of safety. Ladakh does not require heroics from you. It asks for consistency.

When to Turn Back — And Why It Is Not Failure

Few decisions in the mountains are as emotionally charged as the choice to turn back. It is easy, in the moment, to frame it as defeat: the day you “failed” to reach a viewpoint or complete a route. A mature Ladakh altitude guide must confront this narrative directly and dismantle it. Turning back when symptoms worsen, when weather closes in, or when fatigue outpaces enjoyment is not evidence of weakness. It is evidence that you have understood the real stakes: not a photograph, but a safe return.

Practically, the question of when to turn back should be discussed before you set out, not only in the moment of crisis. Agree with your group or guide on clear thresholds: a certain severity of headache, a specific level of breathlessness, or any sign of confusion or loss of balance. Decide in advance that these signs will trigger descent, not debate. This removes some of the emotional drama when the time comes. You are not “giving up”; you are following the plan you created while still thinking clearly.

The deeper lesson is that in Ladakh, success is measured on a different scale. The journey that ends with everyone healthy, with relationships intact and memories fond, is a successful journey—even if a particular pass or viewpoint remained unseen. The bravest travelers are not those who cling to a route at any cost, but those who can look at a high ridge through a pounding headache and say, “Not today.” That sentence, spoken at the right time, is one of the most important tools for surviving and flourishing in the thin air.

FAQ: Ladakh Altitude and Safe Acclimatization

How many days should I plan in Leh before going higher?

For most healthy travelers arriving from low altitude, two to three nights in Leh before sleeping anywhere higher is a wise minimum. Think of these days not as “lost time,” but as the essential base of your Ladakh altitude guide. During this period, keep activities gentle: short walks around town, easy visits by vehicle, and plenty of rest. If you have a history of altitude issues, are travelling with children, or know that you adapt slowly to physical changes, consider extending this to three or even four nights. The extra time will almost always be repaid with a more comfortable, flexible journey later in your itinerary.

Can I visit Nubra and Pangong on a short holiday and still acclimatize safely?

It is possible to visit places like Nubra or Pangong on a shorter trip, but only if the structure of your itinerary respects the staircase of altitude. A responsible Ladakh altitude guide will suggest at least two nights in Leh first, followed by carefully paced travel, ideally with no single day combining long drives, sharp altitude gain, and strenuous hiking. On very short holidays, it may be wiser to choose one higher region rather than trying to reach every famous spot. Fewer destinations, visited with proper acclimatization, will feel far richer than a rushed circuit that leaves you exhausted, anxious, or unwell for half your stay.

Do I really need medication for altitude, or can I rely on natural acclimatization?

Medication for altitude can be helpful in some cases, particularly for travelers with a known history of difficulty at elevation, but it should never be a substitute for good planning and gradual ascent. Any decision about tablets should be made in consultation with a medical professional who understands your health history, not simply copied from an online forum or a friend’s experience. A thoughtful Ladakh altitude guide emphasises that the most powerful “medicine” remains time: enough days in Leh, conservative daily gains in sleeping altitude, plenty of rest, and honest listening to symptoms. Tablets may play a supporting role, but they cannot rescue an itinerary that is fundamentally too fast or too ambitious.

Is Ladakh altitude safe for first-time high-altitude travelers from Europe?

For most healthy visitors, Ladakh can be a safe and rewarding introduction to high-altitude travel, provided the trip is designed with humility rather than bravado. The fact that you have never slept this high before simply means you should give yourself extra time to adapt, build in rest days, and avoid overpacked schedules. A good Ladakh altitude guide exists precisely to help first-timers understand what to expect and how to respond. If you come prepared to slow down, to adjust plans when necessary, and to treat any serious or worsening symptoms as non-negotiable reasons to descend, your first encounter with Ladakh’s thin air can be not only safe, but quietly transformative.

Conclusion — The Kind of Travel Ladakh Asks of Us

To Travel Well Is to Travel Slowly

In the end, altitude in Ladakh is less a technical problem to be solved than a question about what kind of traveler you wish to be. You can approach the region as a challenge to be conquered quickly, ticking off passes and viewpoints while your body struggles to keep up. Or you can accept what every honest Ladakh altitude guide tries to say between the lines: that the mountains are offering you an invitation to slow down, to listen, and to relinquish the illusion that everything important can be done in a few compressed days.

To travel well here is to trust that rest days are not wasted time, that turning back can be the bravest choice, and that the most lasting memories are often made not on the highest ridges but in the quiet courtyards, dim homestay kitchens, and unhurried walks along village paths. When you treat acclimatization not as a bureaucratic obstacle but as a spiritual and physical recalibration, Ladakh responds with generosity. The headaches ease, the breath deepens, and the landscape begins to speak in full sentences rather than fragments.

If there is a single closing note worth carrying home, it is this: altitude does not exist to frighten you, but to re-teach you how to move through the world. Let this journey be the one where you choose safety over speed, depth over quantity, and attention over urgency. In doing so, you will discover that the true summit is not a point on a map, but the moment when your footsteps, your pulse, and the thin Ladakh air finally fall into rhythm with one another.

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.

His columns trace the fragile balance between modern travelers and timeless high-altitude landscapes,

inviting readers to move more slowly, listen more carefully, and let distance reshape their sense of what matters.