The Stillness That Demands Us Back

By Declan P. O’Connor

Day 1–2: Arrival in Leh and Orientation

First Breath, Second Thought

The aircraft banks and the mountains rise like a ledger of old vows. Leh appears as a precise geometry of white walls and prayer flags, a modest punctuation in a paragraph written by stone. The first breath at altitude is always a small negotiation. Your chest lifts, your will insists, and the air—thin, remote, impartial—answers only with limits. A Ladakh wilderness expedition is not a vacation but a conversation with constraint. The mind, oxygen-starved and chastened, slows into a steadier grammar. Coffee tastes like intention. Footsteps sound louder on the guesthouse stairs. A kettle clicks and the village dogs wake, offering the kind of civic notice that passes for dawn.

Orientation is bureaucratic and sacred in equal parts. Permits are secured with the mild theater of forms, passport photos, and stamps that carry the weight of deliberate borders. Bottled water is stacked. Batteries are counted. I learn the shape of my days: an alternating current of movement and attention. The high Himalaya are not merely big; they are morally scaled. To look at them is to feel a claim upon one’s interior life. It is the quiet demand to become less performative, less loud, more true. I walk the market and buy apricots and salt; I rehearse simple greetings. A monastery bell strikes afternoon into focus, as if to say: simplicity is not the absence of detail but the presence of order. The expedition begins not with a trek but with a tempering—of breath, of appetite, of expectation.

Learning the Local Grammar of Respect

In the small span between airports and passes, there is always a catechism of humility. The driver—steady hands, a rosary of cracked leather on the mirror—speaks of roads opening and closing with storms that move like private negotiations between ranges. He offers advice with the charity of experience: drink water before thirst; eat slowly; let the body learn the elevation instead of declaring it conquered. A Ladakh wilderness expedition has many outcomes, but the successful ones begin with this apprenticeship. The medical kit, the layered clothing, the careful sleep—these are not just logistics; they are ethics. At the guesthouse courtyard, a woman hangs wool to dry, and the afternoon wind lifts each strand as if taking attendance.

Orientation is also the education of appetite. There is butter tea, strong and improbable, and there are thukpa bowls with steam that persuades you to be kinder to the present moment. The market is a map of necessary pleasures: walnuts, sun-dried tomatoes, yak cheese, the patient bargaining that passes time rather than saving it. I adjust camera straps and test the lenses, but I am slow to point at anything. The first photographs, like first prayers, should be quiet. At evening, the town lights rise with modest ambition. I make notes: that we are not here to accumulate views but to practice custody of attention; that the high country makes honesty feel like oxygen; that silence, properly kept, is a form of hospitality. Sleep comes with the firmness of a promise that tomorrow will ask more, and I accept that I have agreed to be asked.

Day 3–4: Hemis National Park — Snow Leopards and Wildlife

What the Cold Cat Teaches

Before the ridgeline draws its blue blade against the morning, trackers point into distances measured in patience rather than meters. Snow leopard country is a seminar in probability. You scan couloirs and talus, looking for a kink in the pattern, a punctuation mark in the grammar of rock. A Ladakh wilderness expedition carries the drama of possibility, but it trades spectacle for reverence. We glass the slopes until thought itself becomes granular. Every shadow suggests a tail; every ledge is an argument for hope tempered by geology. The guides talk softly, as if loudness might alter the contracts animals keep with their terrain. I learn that the cat is as much an absence as a presence, and that devotion often looks like steadiness.

In this park, the ethics of looking are explicit. You do not chase. You do not crowd. You do not let your longing make you careless. The cold burns a civility into the fingers, and the tripod becomes a liturgy of small, precise motions. We find tracks—ellipses stamped into powder—then a spray of urine on a juniper that might be yesterday’s news or this morning’s proclamation. Somewhere, a blue sheep stands in the realm between vigilance and calm. One fox unwinds its brush across snow as if editing the page we are trying to read. The cat remains theory, a beautiful rumor that feels truer than most facts. I write: that desire without discipline is noise; that the best photographs are contracts of witness rather than possession; that the mountain keeps its own counsel and is better for it.

Companions of the Unseen

Even when the leopard refuses to audition for us, the park offers a choir of smaller fidelities. Lammergeiers pass like winged hyphens across a sky of hard light. The river rehearses the long sentence of its thaw. The ibex—horns like parentheses around a quiet argument—demonstrate the grammar of balance. A Ladakh wilderness expedition, paced by this wildlife, replaces the tourist’s appetite with a citizen’s posture. To accept the unseen is to become truer in the seen. Near a warming sun patch, we find the scrape of a snowcock, drifted over, and a single feather, the kind of evidence that makes belief reasonable.

At camp, talk turns from sightings to meanings. We are spread out like footnotes around the stove, where tea upgrades to philosophy. Someone says that patience is faith lived in public. Someone else suggests that altitude exiles irony, for sarcasm has no oxygen up here. The guide smiles into his cup. Night drafts its blue curtains, and a wind explores the seams of our tents. The cat may have watched us all day, approving our modest competence or merely tolerating our clumsy pilgrimages. Either way, we have been corrected. We are guests with better manners than yesterday, and the park, indifferent and generous, permits our gratitude.

Day 5–6: Changthang Plateau — Nomadic Life and Flora

Where Wind Learns the Names of People

The Changthang is less a place than an argument for durability. It is a catalog of winds and distances, a ledger of herds written in hoofprints that the next gust will edit without malice. The nomadic camps—tents black as grammatical marks, smoke rising like commas—teach a social economy made of time and thrift. A Ladakh wilderness expedition seeks wildlife, yes, but it also studies the human cadence that has learned to live at such persuading altitudes. I sit with a family who pour tea that tastes of wood and attention. A child offers a smile that belongs to this climate: unembellished, practical, whole.

Flora here is not lush; it is deliberate. Cushion plants stage their botanical humility between stones. Edelweiss appears like a disciplined hope. Each flower is an essay in restraint, an economy of strategy: grow low, invest in roots, keep your promises. I write their names with the diligence of a beginner, aware that language is a form of respect. Yaks move like slow punctuation across a landscape that refuses melodrama. Salt lakes flash a difficult, metallic beauty. The elders speak of routes as if they were proverbs—tested, repeatable, generous in their caution. Evening gathers with the arithmetic of temperature drop, and stars open like a policy of transparency. The wind names the tents in a language everyone understands.

Commerce, Custodianship, and the Price of Speed

There is a temptation to romanticize nomadism as freedom unbilled. But the camp ledger records costs as carefully as kinship. Education requires distance; healthcare requires time; storms require luck. And yet there is an elegance here, an equilibrium between taking and tending. A Ladakh wilderness expedition taught in campfire light learns that stewardship is a verb of many tenses: what you received, what you maintain, what you will hand on. A herder shows me a repaired saddle, the leather dark with use and oil, and in his hands I see a civic philosophy more durable than slogans.

Speed is the modern prodigal. It throws cash at problems that require relationship. Here, decisions are paid for in patience. Even the plants reinforce the point: persistence beats flourish at this altitude. I walk out among small flowers that keep their courage near the ground and think of cities where we ask too much of each day. The plateau answers by being exactly itself: frugal, exact, true. The night brings a discipline of cold that locates our priorities with ruthless clarity. We sleep because we have earned it. We rise because the horizon has not moved and will not make the courtesy of moving for us.

Day 7–8: Tso Moriri Lake — Birds and Reflections

Water Asks the Sky a Question

Tso Moriri receives clouds the way a scholar receives citations: carefully, with the grace of good memory. The lake’s blue is not the tantrum of a tropical postcard but the polish of altitude: exact, literate, undistracted. Bar-headed geese debate the margins, their calls carrying like a parliament convened in air. A Ladakh wilderness expedition gains another instrument here: reflection. The water drafts a second copy of creation and asks if we are reading either version correctly. Every gust edits the surface footnote; every lull restores the main text. The far mountains sit like moral propositions, and the mind, cornered by beauty, becomes honest.

We photograph, but carefully. The lens is too eager to flatter; the lake prefers witnesses who have rehearsed sincerity. I watch a pair of grebes negotiate a choreography that makes my schedule look silly. The shore is an index of tiny tracks. Even the insects seem to endorse restraint. I sit, and the cold rewrites my posture. In this clean light, ambition loses its swagger and becomes vocation again. The lake is not a mirror so much as a tutor, and by afternoon I understand that my best work here will emerge from hours that look unproductive to anyone in a hurry. Evening arrives like a deliberate signature across water that prefers understatement.

Devotions by the Shore

Some landscapes insist on a liturgy and provide one. I walk the shoreline as if counting prayers, stones clicking in my pocket like conclusions. A parchment of reeds moves with the breeze, and their rustle is the voice of a kindly archivist. The birds alter their volume but never their purpose. I write in my notebook: a Ladakh wilderness expedition is an apprenticeship in consequential quiet. When we stop performing for our devices, we become available to the world that keeps its appointments regardless of us. A child from a nearby hamlet points out a duck with casual authority; I accept instruction with equal cheer.

In high places, life does not raise its voice to be heard. It repeats itself until we learn how to listen.

At camp the stove’s soft roar pulls us into a circle. Stories arrive in a queue: near misses on bad roads, a cousin who saw a leopard, the winter that taught a village how to be a single household. I feel the good impatience of morning building even as night expands. Somewhere across the lake, light leaves the last ridge like a benediction. Silence pays us the respect of expecting our integrity in return.

Day 9–10: Nubra Valley — Desert Landscapes and Bactrian Camels

An Atlas of Sand and Snow

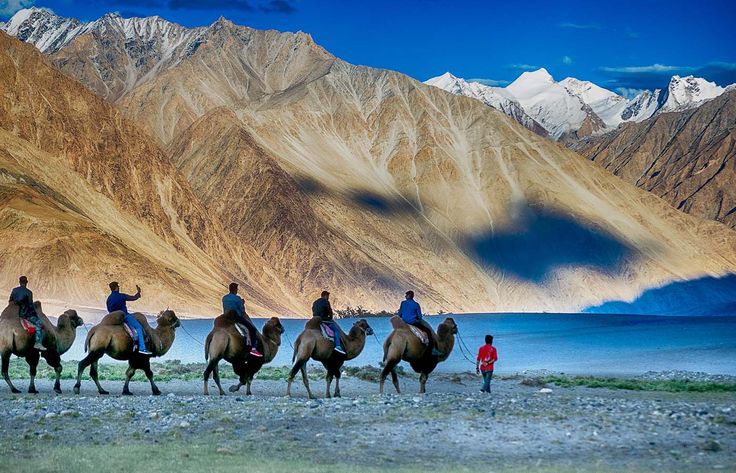

Nubra is a plain where geographies court each other: sand flirting with snow, prayer flags making pacts with dunes, a river cutting legal channels through the argument. The Bactrian camels look like parables with knees. Their silhouettes, double-humped and deliberate, move as if they are escorting the day to its appointment with evening. A Ladakh wilderness expedition that arrives here must adjust its rhetoric. The desert refuses decoration. It prefers nouns: ridge, wind, hoof, light. I understand that the eye, flattered by endless sky, has responsibilities. Perspective is not a trick; it is an ethic.

The dunes are merciful to footprints only until the wind remembers them. We climb a slope that gives back nothing and are rewarded with a view that hands us over to restraint. The camels kneel with the elegance of a well-placed comma, reassembling caravans of older economies. The handlers speak softly, professional kindness made into method. We rehearse the rule that images must be gathered without theft. The river, tired of our metaphors, proceeds to be itself, issuing a daily memo to the valley about the terms of passage. I take few photographs and keep more in a ledger I cannot show anyone. In the desert, ownership is a ridiculous ambition; custody is the better word.

Work That Looks Like Grace

In the villages, labor moves with a choreography of competence. A woman sweeps dust that will certainly return, and the faithfulness of the gesture is its meaning. Fields are stitched with canals that make patience into agriculture. The camels take their breaks with the juridical seriousness of union men, lying in a sand that keeps its promises to heat and cold. A Ladakh wilderness expedition, if it is honest, does not just import awe; it exports attention. Start with names, then with times, then with tasks. The valley’s desert creed is cheerfully precise: do the work, keep the water, share the wind.

At dusk, the cold collects itself and visits with purpose. We huddle near tea and stories. Someone asks about the moral of a desert; someone else proposes that deserts are where ambition and humility meet on neutral terms. I record the suggestion. Stars walk out onto the sky with the unembarrassed punctuality of public servants. The sand cools faster than memory. The camels settle into silhouettes that explain more than any caption could. We sleep, as always, in that fellowship of tents that turn strangers into reliable nouns: neighbor, watchman, friend.

Day 11–12: Pangong Lake — Changing Hues and Birdlife

The Discipline of Color

Pangong is a lesson in tonal revision. It moves through its palette without apology: iron blue to tempered turquoise to a reflective slate that refuses to choose. The sky, apparently pleased to be consulted, edits the lake every minute. A Ladakh wilderness expedition, which has already learned humility in many dialects, learns it here in chromatic grammar. By noon, the water is a prescription for attention; by evening, it is a diagnosis of our limits. Birds make small lines against this enormous essay—the sandpipers brisk, the gulls officious, the terns surgically precise. The shore offers a catalog of stones that professionals of patience would admire.

We calibrate our lenses like priests attending to vessels. The exposure demands honesty. The wind, never wrong, arrives with a briefing on how to hold still. An old herder tells me the lake has moods the way a good person has convictions: it changes, but within a faithful range. I write down the shape of the waves, which looks like thought corrected by reality. The mountains on the far side are the minutes of a meeting between time and stone; they record without embellishment. In the evening, the colors simplify into a sober navy, and the heart opens as if signing onto a resolution that was already drafted before we were born.

Birds as Arguments for Patience

Birds make a civic order out of open air. They are the most disciplined of libertarians: free, yet governed by necessity. I watch bar-headed geese whose passports are stamped by altitudes that would embarrass aircraft. Their flightpath is an editorial that needs no corrections. A Ladakh wilderness expedition earns its diploma when it stops counting sightings and begins practicing regard. A child on the shore counts aloud with the grace of a bell, and I realize that identification is less important than intercession: to watch in such a way that the watched world is safer for being seen.

Later, in a quieter bay, a small flock tucks in along a line that the wind respects. I could stay for hours, and do. The light leaves in orderly fashion. A gull, late to the meeting, lands with the surprised dignity of those who assume agendas are optional. The lake makes small weather inside my chest. I am rarely so grateful to be unimportant. The day closes with the unceremonious competence of a seasoned clerk, and I sign off with a nod to water that never once asked me to admire it.

Day 13: Review and Departure

Inventory of a Changed Appetite

Departure is an audit. Bags are repacked, batteries mostly spent, notebooks fattened into a more honest shape. I make a list of what I am taking and what I hope to leave behind. A Ladakh wilderness expedition that began in ambition concludes in a plainer hunger: to keep company with places without trying to own them. I find the apricot vendor and buy a second bag for gifts; I pay too much with cheerful incompetence. The driver shakes my hand like a verdict and says we were lucky with weather, which is true but incomplete. We were also lucky with our own minor conversions—those small daily decisions to be gentler with land, with animals, with each other.

The flightline is a theater of small delays and larger farewells. I look at the mountains and imagine them as minutes kept on a divine calendar. They will continue, unsentimental and kind, to hold their shape. If there is a thesis, it is this: that wilderness educates conscience as much as it entertains imagination. In the quiet arithmetic of altitude, ambition is refined into vocation, and vocation into gratitude. The plane hums, the runway shortens, and the mind—tired, enlarged, corrected—commits a final note: carry this hush home and spend it like a serious person spends time.

FAQ — Practicalities for a Thoughtful Journey

Q: When is the best season for this itinerary?

A: Late autumn and late winter each have virtues: clear light, fewer crowds, and an honesty of weather that rewards preparation. Shoulder seasons offer birdlife at the lakes and a civic quiet in villages. Choose dates that honor acclimatization and stamina rather than fitting adventure into idle weekends.

Q: How difficult is the acclimatization?

A: The itinerary gives your body time to learn. Drink before thirst, walk slower than pride would prefer, and sleep like it’s part of the plan—because it is. Headaches are petitions; answer them with water, rest, and humility. If symptoms escalate, descend without bargaining.

Q: What gear is essential beyond the usual?

A: Insulating layers that stack without drama; windproof shell; broken-in boots; sun hat with convictions; water purification and a sense of proportion. Photographers should bring restraint along with filters. A small notebook will outlast any battery and may teach you better habits of attention.

Q: How do I travel responsibly in wildlife areas?

A: Distance is a form of love. Stay on established lines. Let guides set the tone. If an animal alters its behavior because of you, you have already said too much. The best images are taken with permission—if not explicitly given, then at least not revoked by alarm.

Q: Is connectivity reliable?

A: It is intermittent, which is not a bug but a feature. Tell those who need telling, then allow silence to do its corrective work. The conversations you keep with wind and water will not trend, and therefore may matter.

Conclusion — What the Mountains Ask of Us

The thesis of these days is not that the world is beautiful, though it is, relentlessly. It is that beauty requires a moral answer. The high Himalaya ask for patience made public, for gratitude expressed in habits, for attention spent like currency with a traceable ledger. A Ladakh wilderness expedition does not graduate us into better people; it drafts us into a better practice. The cat may remain unseen; the lake may change its mind hourly; the sand may offer nothing but the arithmetic of wind. Yet the soul, properly addressed, grows practical: slower to speak, quicker to serve, steadier in weather. If we are fortunate, we come home with fewer opinions and more convictions.

Closing Note — Carry the Quiet

Take what the altitude gave: the decency of unhurried mornings, the respect that distance teaches, the vigilance that wildlife demands, the discipline of color at lakes that never once bragged. Pack them into your city hours. Let your errands be slower and your arguments more carefully punctuated. The work of being human is not louder after Ladakh; it is clearer. Carry the quiet the way skilled hands carry a bowl of water over rough ground—level, attentive, grateful. Spend it in public. Let it spill only on purpose, and only where it might make something grow.