Threads of Silence: Life Among the Changpas

By Elena Marlowe

Prologue — The Cold That Teaches Warmth

When the wind becomes a teacher

At dawn on the Changthang plateau, the wind is the first voice you hear. It moves across a land so wide it defies the idea of boundary—an altitude between 3,900 and 4,500 meters, stretched eastward toward Tibet. This is Ladakh’s remote southeast, a high-altitude desert receiving less than fifty millimetres of rain a year. In this vast silence live the Changpas, the nomadic herders whose entire existence unfolds between stone, snow, and sky. Their home is not fixed; it migrates with the rhythm of life itself. To the untrained eye, it may seem like exile. To them, it is belonging in motion, a geography learned by heart.

The geography of endurance

Ladakh, caught between the Karakoram and Zanskar ranges, sits at the top of the world—where the air is thin, the stars are close, and the horizon feels alive. Yet even here, survival is neither miracle nor accident. The Changpas’ lives are structured by necessity: altitude determines the heart rate, wind dictates the calendar, and the snow defines the boundary between possible and impossible. The region’s administrative nucleus, the Nyoma Block, was established in 1966 and encompasses seventeen small villages such as Samad, Kharnak, Rupshu, and Korzok. Each functions less like a permanent settlement and more like a seasonal constellation. Hanle, home to one of the world’s highest observatories, peers at the galaxies from above 4,500 meters—but below, the Changpas still navigate by the same constellations, as their ancestors once did.

The Changpas — People of the Wind

Nomads of adaptation

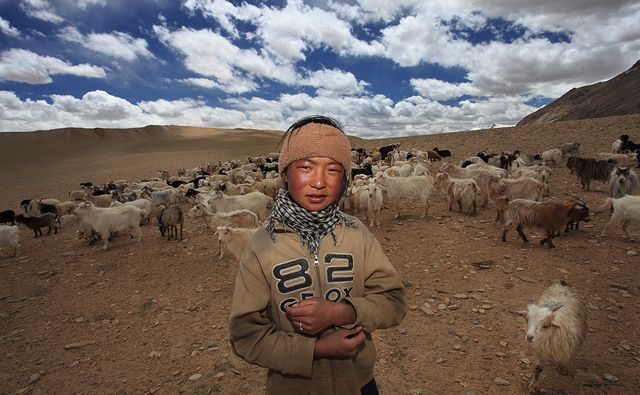

The Changpas are not relics of the past; they are practitioners of one of the world’s most sophisticated ecological systems—mobile pastoralism. Each household owns a combination of sheep, yaks, and the prized Changra goats, the source of Pashmina. During the warmer months, families live in yak-hair tents called rebos, durable against wind yet portable enough to follow the grass. In winter, they retreat to small stone and mud homes, clustered near frozen streams. Their economy is built not on excess but on exchange—between human and animal, land and sky. This balance, sustained for centuries, remains the core of Ladakh’s intangible heritage.

Polyandry and the politics of survival

For generations, the Changpas practiced polyandry—a woman marrying multiple brothers within the same household. It was not born of romantic abstraction but practical genius. In a landscape that could not afford division, the system prevented fragmentation of property and preserved the collective labour needed to sustain herds. The government banned it in the 1940s, declaring it regressive. Yet, the ban disrupted the delicate balance that had long held social and ecological systems together. Labour shortages followed. More mouths meant smaller herds and less mobility. A 2020 study notes that some older women still defend the practice—not out of nostalgia but recognition that in an environment of scarcity, cooperation was the purest form of love.

Pashmina — The Economy of Fragility

The Changra goat and its geography

Among Ladakh’s living symbols, none is as economically vital—or culturally misunderstood—as the Changra goat (Capra hircus). Its undercoat produces the world’s finest Pashmina fibre, finer than a human hair and capable of holding warmth through the harshest Himalayan nights. Each family owns, on average, about one hundred goats, yielding roughly 22 kilograms of fibre annually. At the market rate of ₹3,000 to ₹3,500 per kilogram, this equates to approximately ₹77,000 in annual income. Alongside, their sixty sheep produce 90 kilograms of coarse wool, earning an additional ₹6,700, and two yaks sold each year bring in ₹40,000. In total, an average household earns between ₹150,000 and ₹200,000 annually—a modest sum by any standard, but a lifeline in a land where alternatives are few.

The paradox of luxury and labour

Pashmina is a paradox. In the valleys of Leh and in boutiques of Delhi, it is a symbol of luxury and elegance—grace draped across shoulders in distant cities. But its creation begins in the cold silence of the plateau, in hands cracked from wind and salt. Fifty percent of a Changpa family’s income is spent on buying barley and fodder, as the pastures can no longer sustain their growing herds year-round. Inflation and unpredictable subsidies squeeze margins further. The barter economy that once tied nomads to settled farmers has dissolved, replaced by a cash economy that offers no stability. A woman in Kharnak once told a researcher, “Before, we had less money but more certainty. Now, we have neither.”

The role of policy and its gaps

Government intervention exists but remains inconsistent. The Sheep Husbandry Department runs selective breeding programs, provides veterinary training, and offers subsidies covering up to 50% of fodder costs. Yet, these measures rarely reach the plateau’s farthest corners, where altitude is a barrier not only to breath but to bureaucracy. Nomads travel days to access a veterinary centre; fodder delivery often arrives after the snow. Meanwhile, cooperatives established to stabilize prices sometimes function only on paper. The infrastructure of support—the roads, cold-storage chains, digital banking—ends where the road turns to dust. Pashmina’s value chain stretches across continents, but its foundation still rests on the back of a single goat chewing sparse grass beneath a Ladakhi sky.

The hidden environmental cost

As herds increase to meet market demand, pastures suffer. Overgrazing has begun to degrade the delicate alpine soil, displacing wild herbivores like the kiang and bharal that once shared the same ecosystem. Climate change compounds the crisis: warmer winters disrupt breeding cycles, and erratic snowfall limits natural water storage. The Changpas find themselves caught between survival and stewardship—pressed by economic need to expand herds even as they witness the land’s exhaustion. For centuries, they lived as stewards of equilibrium. Now, they are asked to be producers in a global supply chain that neither sees nor understands their fragility. And yet, amid all these contradictions, they endure. Each fleece combed, each shawl spun, carries the echo of that endurance—a quiet dialogue between necessity and grace.

Tradition in Transition

1962 — When the mountains were divided

The year 1962 cut through the Changthang like a fault line. The Sino-Indian conflict redrew borders that had, until then, been only ideas in the snow. Soldiers arrived, roads were blasted through ancient grazing grounds, and the silence of the plateau became strategic. Tibetan refugees crossed into Ladakh, bringing their own herds and customs, compounding pressure on fragile pastures. The Changpas, suddenly fenced by borders, lost access to winter grazing lands that had anchored their migration for generations. The loss was not just spatial but spiritual: to a nomad, every path is a prayer. With the line on the map, those prayers were interrupted mid-sentence.

The slow pull of the city

Leh, once a remote trade post linking Central Asia to India, has become a magnet for those seeking education, medicine, and modern dignity. About one in three Changpa households now lives near the city’s fringes. The change seems inevitable, even logical—who would choose hardship over healthcare? Yet the cost is not counted in rupees but in rhythm. In the city, time no longer moves with the wind but with the clock. Old men, who once read the clouds to predict snow, now stare at mobile screens showing weather for a sky they cannot smell. Many grow ill, not from disease but from the dislocation of memory. “We dream of the wind,” one told a researcher, “but here, it does not visit.”

Education and the language of forgetting

Across Nyoma Block, forty government schools serve scattered settlements, many operating from canvas tents that fold at the first storm. Attendance drops each winter when families move or roads close. To secure education, parents send children to boarding schools in Leh or Srinagar. It is an act of hope—but also an exile. The young learn English and Hindi, not Changskat; they return speaking to their grandparents through translation. With every report card, an oral culture fades further. Development brings literacy, but it also teaches forgetting. A grandmother in Samad once whispered, “When my granddaughter reads books, she forgets our stories.” Between enlightenment and loss lies the price of progress.

Shifting Landscapes of Survival

The arithmetic of scarcity

Statistics tell the story plainly: half of household income spent on fodder and grain; veterinary centres two days away; electricity unreliable; healthcare distant. There is no sanitation network, and drinking water is collected directly from streams that freeze for months. Diets rich in butter tea and roasted barley keep bodies warm but lack essential vitamins. Frostbite and eye infections are common. Women bear the weight of endurance—tending fires, milking yaks, spinning wool, raising children who may never return to the plateau. Every household is both a family and a frontier. When snow seals the roads, even a fever can turn fatal. In a global economy obsessed with speed, the Changpas live by a different mathematics: patience divided by necessity, multiplied by faith.

Infrastructure and the illusion of inclusion

Official reports highlight schemes for animal insurance, pasture regeneration, and veterinary training. Yet implementation falters where altitude begins. Trucks carrying fodder overturn on icy passes; mobile towers fail in winter; bank accounts remain theoretical for those without connectivity. Development here is often a story of distance—between policy and plain, promise and plateau. “They come with cameras and notebooks,” one herder said, “but not with fodder.” The administrative imagination still pictures progress as concrete: roads, buildings, machines. But in Ladakh, resilience has never been built from cement. It has been woven, like Pashmina—thread by thread, season by season, held together by memory more than material.

The changing ecology of belief

For centuries, monasteries governed migration through astrology and ritual. Before a move, monks performed the lha-tse ceremony, asking local deities to bless the herds. Today, these rituals survive but coexist with government notifications delivered by SMS. Faith and technology now share the same sky. Some younger herders carry solar panels and satellite phones; others play Bollywood songs beside sacred lakes. The world has reached the Changthang, not as invasion but as diffusion. And yet, even amid these collisions of time, a quiet continuity endures. Every journey still begins with an offering of butter at dawn. Progress has not erased reverence—it has merely changed its vocabulary.

Between Policy and Memory

The invisible majority of the highlands

To the outside world, the Changpas are few—only a few thousand families scattered across an uncharted desert. But they are the custodians of a resource that sustains an entire economy downstream. Without their labour, Pashmina would not exist; without their herds, Leh’s markets would fall silent. Yet their representation in policymaking remains almost nonexistent. Meetings about “sustainable development” often occur in conference rooms they will never see. The idea of inclusion, ironically, excludes those who live farthest from the centre. The silence of the plateau becomes their invisibility.

Dependency and dignity

Cash has replaced barter, but it has not replaced uncertainty. Taxes must now be paid in rupees; goods once exchanged through trust are bought at fluctuating prices. Inequality deepens between households with large herds and those forced to sell animals after a bad winter. Poverty here is measured not in possessions but in distance—from markets, from schools, from recognition. Yet the Changpas retain an uncommon dignity. They still greet strangers with salted tea and the phrase julley—a word that means hello, goodbye, and thank you all at once. It contains an entire philosophy of coexistence: that everything, even hardship, is shared.

Conclusion — The Philosophy of Stillness

Listening to the wind again

Across the Changthang, silence is not emptiness. It is structure—a way of knowing. The herders who cross these plains each season are not remnants of a vanishing world; they are the living grammar of balance. Their lives, recorded in every hoofprint and woven into every shawl, remind us that civilization is not a synonym for comfort. It is the art of remaining human in difficult terrain. A 2020 report concluded that “pastoralism and Pashmina production form a cultural asset of Ladakh, yet the absence of infrastructure and coherent policy threatens their survival.” The Changpas, however, are not waiting to be saved. They are waiting to be understood.

The enduring thread

Somewhere in Kharnak, a woman rises before dawn, lights a dung fire, and begins combing a goat’s soft undercoat. Each stroke gathers not only fibre but memory. That fibre will travel hundreds of miles, cross oceans, and rest finally on the shoulders of someone who may never know her name. And yet, the warmth they feel will be hers. The Pashmina shawl is not a luxury item; it is geography made tangible—altitude, silence, endurance turned to grace. Perhaps that is the real economy of Ladakh: the transformation of hardship into beauty, and of isolation into meaning. The Changpas have always known this. They do not measure wealth in rupees but in mornings survived, journeys completed, and winds remembered.

Closing note: To live in the Changthang is to live in conversation with the earth. Its silence asks questions no city can answer. The Changpas’ endurance is not nostalgia—it is instruction. It teaches us that survival and serenity can share the same horizon.

The narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh

A storyteller exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.

Her work reflects a dialogue between inner landscapes and the high-altitude world of Ladakh.