The Memory Beneath the Mountains

By Elena Marlowe

Prelude — When the Sea Slept Under the Sky

The Whisper of Salt in the Wind

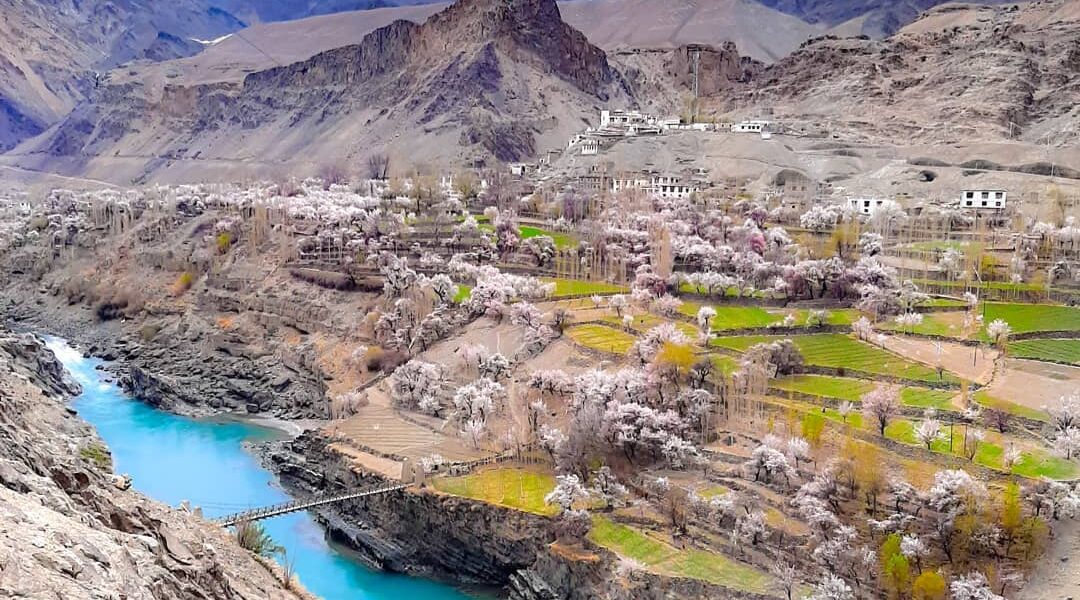

There are mornings in Ladakh when the air itself feels ancient, like a page turned slowly in the book of the world. Standing above the Indus valley, the wind carries a faint taste of salt. It is a taste that should not belong here, at nearly 3,500 meters above sea level, yet it lingers — as if the ocean never truly left. The rocks, silent and immense, seem to hold within them a memory of water. This is where the story begins: a sea that dreamed itself into mountains, a place where when the rocks remember the sea.

Scientists call it the Tethys Ocean, a vanished sea that once lay between India and Asia. Millions of years ago, it stretched where the Himalayas now rise. The Indian plate, restless and insistent, began its slow drift northward — a movement measured not in years but in heartbeats of stone. When the plates finally met, the sea was lifted toward the sky. The sediments, once soft with marine life, hardened into limestone and shale, now weathered by Himalayan winds. To walk here is to walk upon the seabed of eternity.

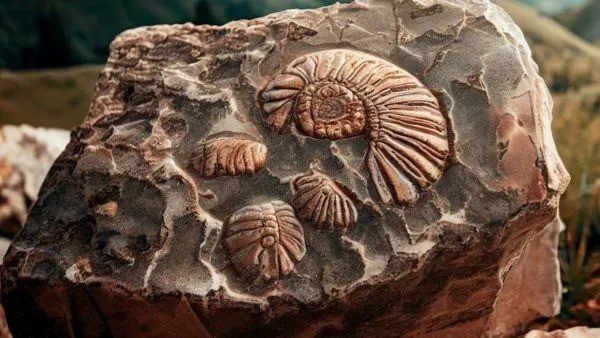

For the traveler, Ladakh offers not a landscape but a lesson in patience. The mountains remind us that everything changes form — water into rock, rock into dust, dust into silence. In these transformations, the Earth teaches humility. It whispers that creation and erosion are simply different verses of the same song. And somewhere beneath your feet, an ammonite fossil sleeps — a spiral-shaped proof that memory, once buried, never truly dies.

The Sea That Became a Mountain

The Slow Collision of Worlds

Long before humans measured time, the Earth was already scripting its vast poetry. The collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates was not an explosion but a gradual, deliberate embrace. It began deep beneath the Tethys Ocean, where molten rock pulsed upward, forming volcanic arcs now frozen in stone — the Ladakh Batholith, the heart of the Trans-Himalayan range. Every granite vein tells a story of heat, pressure, and transformation. When you touch these rocks, you are touching time condensed into texture.

Geologists read these layers the way monks read manuscripts. Each stratum reveals a line of history: marine fossils pressed into limestone, volcanic minerals shimmering under sunlight, metamorphic folds curving like the breath of the Earth. The Indus Suture Zone, running like a scar through the valley, is the meeting point of continents. It is where oceanic crust was swallowed, melted, and reborn as mountain. Yet in this violence, there is grace — the beauty of form born from friction. The mountains are not static monuments; they are gestures caught in motion, still rising, still remembering.

In local myth, the peaks are seen as deities asleep under white blankets. The science only deepens that faith — for these gods are real, if slow. Their dreams last millions of years, their awakenings carve rivers. The Himalayas are living beings, breathing in tectonic rhythms, exhaling through landslides and erosion. What we call landscape is merely the present tense of geology’s long meditation.

Where Continents Kiss — The Indus Suture Zone

Between the dusty cliffs near Nyoma and the gentle arc of the Indus River lies one of the most significant geological features on Earth: the Indus Suture Zone. Here, the boundary between two ancient worlds is visible to the naked eye — a meeting of metamorphic rocks from the Indian plate and volcanic sequences from the Trans-Himalayan arc. This narrow corridor marks the final union of continents that once drifted apart. To the untrained eye, it is just a band of fractured stone, but to those who listen, it is the Earth’s pulse, still throbbing beneath the surface.

Every boulder, every grain of sand tells a story of movement. The black schist layers record the immense pressure of subduction; the lighter granites tell of magma’s escape to the surface. The entire valley is a museum of motion frozen mid-act. And yet, it is strangely peaceful — as if the Earth itself exhaled after a long tension. Travelers often describe a sense of calm here, a feeling that time has folded in on itself. Perhaps that is what memory feels like on a planetary scale: the silence after collision, the stillness after creation.

Fossils of Time — When Rocks Hold Memory

Reading the Stone Script

High above Lamayuru, among slopes of ochre and silver, you may find the spiral imprint of an ammonite — a tiny relic of the Tethys Sea, curled like a secret. Once, it drifted through warm marine waters. Now it lies in cold dust beneath a sky of perfect blue. The fossil does not speak, but its form tells of patience beyond imagination. It is a record of life transmuted into permanence. To hold one is to feel the distance between the living and the eternal collapse into your palm.

These fossils are scattered across Ladakh like punctuation marks in the Earth’s memoir. Some lie embedded in limestone walls, others revealed by landslides or wind. They remind us that memory is not only human — the planet, too, remembers. Its memory is written in strata and stone, in minerals that once shimmered beneath a shallow sea. Even the colors tell stories: the gray of an ancient seabed, the pink of oxidized iron, the white veins of calcite that crystallized from prehistoric water. Together, they form a palette painted by time itself.

The Philosophy of Geological Memory

What does it mean for stone to remember? To remember is to resist oblivion, to carry forward what would otherwise be lost. The fossils of Ladakh do this wordlessly. They remind us that memory is not always a matter of consciousness — sometimes it is endurance. Perhaps we, too, are made of such endurance, layers of memory hardened by pressure. The rocks teach us that time is not a line but a spiral — always returning, never repeating. The Earth’s recollections are not nostalgic; they are structural, embedded in its very bones.

When I sit among the shale ridges of Zanskar, I often think of how fragile memory is in human hands. We forget people, years, even our own intentions. But the Earth forgets nothing. Its memory is impartial, precise, and unhurried. In a world obsessed with immediacy, geology is the art of patience. To look at these mountains is to confront the truth that all stories, if told long enough, become stone.

Veins of Light — Stones That Breathe

The Language of Quartz

Deep within the ridges near Hemis, veins of quartz glint under the midday sun like frozen lightning. These mineral threads were once channels for molten fluids coursing through fractures in the Earth’s crust. Over millennia, they cooled and solidified, forming luminous scars across darker granite. Locals call them “light veins,” believing they guide wandering souls through the mountains at night. Science calls them hydrothermal deposits, but both explanations share a reverence for the unseen forces that shape the visible world.

The quartz veins are the Earth’s handwriting in crystal form. Each crack tells of strain, each shimmer a record of release. If you run your fingers along them, you can almost feel movement — not metaphorical but mechanical, a whisper of expansion and cooling. The mountain’s surface becomes a breathing skin. In the right light, these veins reflect the sky, uniting stone and air in a moment of pure clarity. This, perhaps, is the pulse of the planet made visible.

The Breath Beneath the Surface

To imagine the Himalayas as static is to misunderstand them. Beneath every silent valley lies motion — magma rising, plates grinding, rivers carving new paths. Even the permafrost breathes, expanding and retreating with each season. The Earth, like us, is restless. Its respiration is slow, but constant. When the wind slips through gorges and the ground hums faintly underfoot, that is the Earth exhaling — a reminder that our stillness is temporary.

In this living geology, one begins to sense kinship. The rocks do not resist time; they collaborate with it. They erode gracefully, transforming into soil, then into sediment, and eventually into stone again. The cycle repeats, endlessly, beautifully indifferent to human timelines. The more one observes, the clearer it becomes: permanence is only the illusion of slow motion.

Silence as a Landscape

Where Stillness Becomes Sacred

Silence in Ladakh is not the absence of sound but the presence of space. It fills the valleys between thoughts, the pauses between words. The geology itself amplifies it — vast cliffs that echo whispers, dry riverbeds that muffle steps. This silence is geological, not emotional. It is the residue of vanished oceans and ancient winds. In monasteries perched above the valleys, monks chant to this silence as if in dialogue with the mountain itself.

There is a strange comfort in realizing that silence and stone are kin. Both endure without complaint. Both record without judgment. For travelers accustomed to noise, the quiet of Ladakh can be unsettling at first. Yet, if one stays long enough, the silence becomes language — a dialect of patience and surrender. It teaches that listening is a geological act: you must be still long enough for echoes to return from the deep.

The Sacred Geometry of the Horizon

Viewed from above, Ladakh’s horizons draw perfect geometries — triangles of shadow, circles of prayer flags, spirals of windblown dust. Each shape mirrors the mathematics of creation. The ancient builders of chortens and stupas seemed to know this instinctively: that geometry is the syntax of the universe. The same ratios that govern mountains govern our hearts — symmetry, balance, proportion. When the light falls just so on a ridge of folded limestone, it reveals the same grace as a mandala traced in sand. In both, there is impermanence and completion.

“Perhaps the mountains are not rising toward heaven,” I once wrote in my notebook, “but remembering the sea they once belonged to.”

The River That Remembers

The Indus as a Living Archive

The Indus River flows like a vein of silver through the desert — patient, persistent, eternal. It carries with it the silt of countless ages, particles once part of coral reefs and volcanic peaks. As it carves through Ladakh, the river tells a story in layers: how the sea retreated, how the mountains rose, and how life adapted to both. Each bend of the river is a page in this hydrological scripture.

Along its banks, small villages cling to terraces carved from stone. Their barley fields shimmer like islands in an ancient ocean of dust. The people who live here understand the river’s dual nature — giver and eroder, memory and movement. They call it the Singe Khababs, the Lion’s Mouth, a name that evokes both power and reverence. Watching its slow curve at sunset, one feels the impossible intimacy between water and rock, each shaping the other endlessly.

Water, Stone, and the Circle of Return

There is a quiet irony in the way water, which once drowned these rocks, now liberates them. Erosion is simply another form of remembrance. The river unburies the past, revealing fossils, minerals, and layers of forgotten seas. It writes and erases with the same hand. In Ladakh, water and stone are not opposites; they are collaborators in creation. Together, they compose the landscape, like poet and editor, each revising the other’s work across centuries.

And so the Indus flows, patient as breath, reminding us that the memory of water is never lost — only transformed. What once was sea is now river; what once was motion is now mountain. In its flow, the river holds the promise of return.

Epilogue — Stones That Dream of the Sea

The Stillness After Creation

At dusk, when the last light fades from the cliffs of Lamayuru, the land seems to breathe again. Shadows stretch across the valley like pages closing. The air cools, carrying the scent of dust and juniper. Somewhere, far below, the fossils rest — ammonites, coral fragments, silent witnesses of an ocean’s dream. Above them, prayer flags tremble, as if stirred by an unseen tide.

To stand here is to feel the impossible: the sea rising into the sky, the sky sinking into stone. It is to recognize that memory is not bound by time but by transformation. The mountains are archives of movement; the rocks are the planet’s autobiography. And we, brief visitors in their long story, are invited to listen — to remember that everything we touch once belonged to something else. Perhaps this is the true lesson of Ladakh: to see not the end of the sea, but its continuation in another form — still flowing, still alive, beneath our feet.

FAQ

Was Ladakh once under the sea?

Yes. Millions of years ago, Ladakh was part of the Tethys Ocean. The movement of tectonic plates lifted the seabed into what are now the Himalayas. Fossils across Zanskar and Lamayuru provide visible proof of this transformation.

Where can visitors see marine fossils in Ladakh?

Fossils are often found around Lamayuru, Zanskar, and near the Indus valley. However, visitors are encouraged to observe without collecting, preserving these natural archives for future generations and scientific study.

What is the Indus Suture Zone?

The Indus Suture Zone marks the boundary between the Indian and Eurasian plates. It is a geologically significant belt that records the collision and uplift that created the Himalayas, visible near the Indus River.

How old are the rocks in Ladakh?

Many rock formations in Ladakh date back between 40 and 200 million years, spanning from marine sedimentary rocks to volcanic sequences formed during plate convergence and uplift.

Why is Ladakh considered a geological wonder?

Ladakh exposes nearly every stage of mountain-building in one landscape — from fossilized seabeds to active fault zones. It is both a geological archive and a philosophical mirror of transformation.

Conclusion

The story of Ladakh is not about stone alone; it is about time, endurance, and the poetry of transformation. The mountains do not shout their history — they whisper it through fossils, veins of quartz, and silent horizons. To travel here is to read the Earth’s diary, written not in ink but in sediment and sky. When the rocks remember the sea, they remind us that change is not destruction but continuity in another language. And if we listen closely enough, we may hear the ocean still speaking — through the breath of the mountains, through the pulse of the Earth, through the silence that endures.

She is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective exploring the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.

Her work reflects a dialogue between inner landscapes and the high-altitude world of Ladakh,

where philosophy and geography often share the same breath.