Introduction – When Sustainability Climbs High and Dives Deep

From Nordic Roots to Himalayan Heights

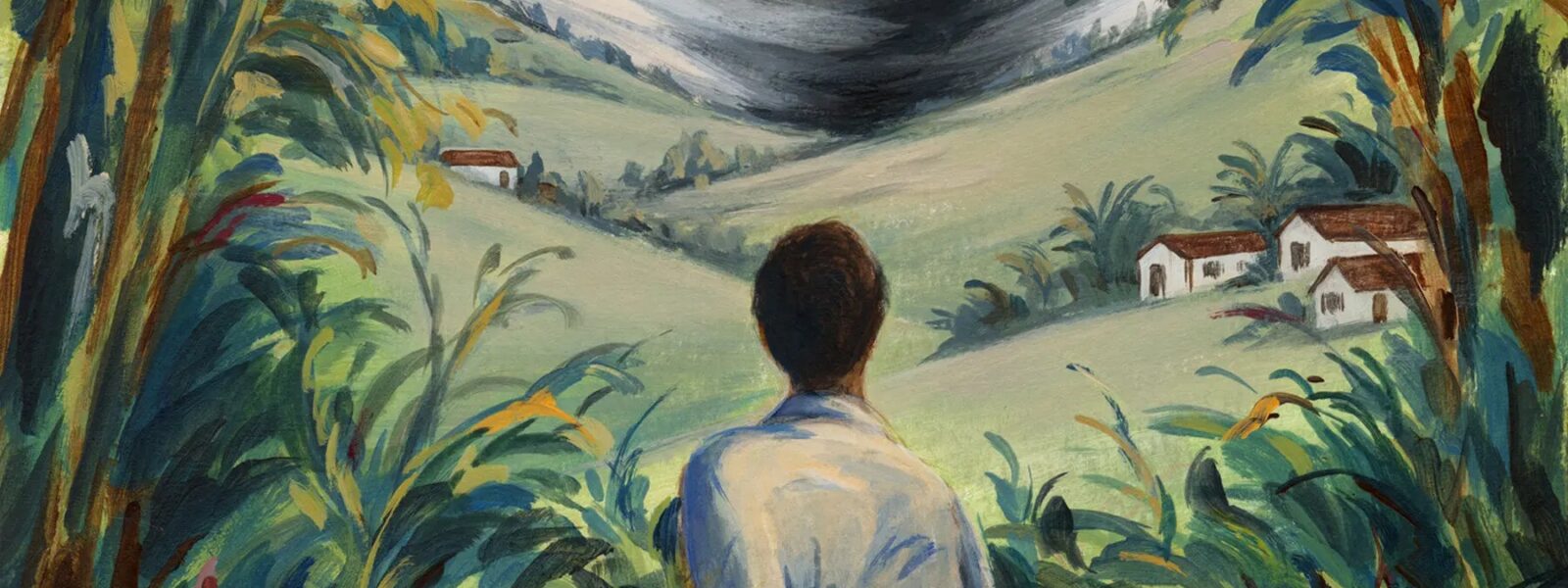

There are moments when the silence of a place speaks louder than any word. I remember one such moment vividly: floating in the steaming waters of an Icelandic geothermal spring, my eyes tracing the horizon where volcanic rocks met dancing northern lights. And months later, a different silence greeted me—thin, crisp, reverent—as I stepped onto the sunburnt plateau of Ladakh for the first time. The contrasts were stark. The connection, however, was immediate.

This column was born from that contrast. Iceland, a land sculpted by ice and fire, has become a poster child for sustainable tourism in Europe, where green energy meets sleek Scandinavian infrastructure. Ladakh, on the other hand, is less known to European travelers, but no less remarkable. Tucked between the peaks of the Indian Himalayas, its villages operate not on electricity or concrete, but on rhythm, memory, and sun. Here, I found what I believe is one of the world’s most authentic expressions of high-altitude ecotourism.

As a regenerative tourism consultant, I’ve spent years studying how destinations adapt to climate pressures, economic challenges, and shifting traveler values. I’ve seen sustainability become a buzzword in brochures, a checkbox on booking sites. But in both Iceland and Ladakh, it is something else entirely. It is lived. It is necessity. And it is woven into the very fabric of the land.

This article explores these two vastly different worlds, not to determine which is “better,” but to understand what each teaches us. What does it mean to build an eco village at 3,500 meters, powered by solar stoves and meltwater channels? What lessons can Ladakh offer that Iceland cannot? And vice versa? By holding up these places as mirrors, we may discover what sustainable travel really looks like—beyond branding, beyond luxury, and beyond the Western gaze.

If you’re a traveler from Paris, Berlin, or Barcelona, seeking a meaningful connection to place—not just scenery—this journey is for you. It is for those who no longer want to consume destinations but understand them. As we begin, I invite you to leave behind what you think you know about ecotourism. Whether you’re drawn to Iceland’s geothermal grace or Ladakh’s solar wisdom, you’re about to experience how sustainability can take radically different forms—both inspiring, both essential.

Iceland – The Laboratory of Natural Energy

Geothermal Grace and Eco Logic

Iceland is, in many ways, a frontier nation—not in the colonial sense, but in its unrelenting embrace of nature’s extremes. Here, the land simmers just beneath the surface, and humans have long learned to live in partnership with this geothermal power. As a traveler, the experience of stepping into a hot spring surrounded by snow-covered lava fields is more than relaxing—it’s revelatory. You feel not like a visitor, but like a welcomed participant in Earth’s deep-time processes.

The nation produces over 99% of its electricity from renewable sources, primarily geothermal and hydropower. This is not simply a triumph of engineering—it’s a philosophy of cohabitation. Towns like Hveragerði and Mývatn run on natural heat, with greenhouses glowing like lanterns in the long Arctic nights. Even Reykjavik’s sidewalks are heated, not by indulgence, but to reduce salt usage and protect river ecosystems. This is where green infrastructure becomes both elegant and essential.

For European travelers who come from urban centers still struggling to decarbonize, Iceland can feel like a hopeful postcard from the future. It’s a place where eco-conscious tourism has grown alongside environmental policy, not in spite of it. Here, taking an electric bus to a glacier hike isn’t a marketing gimmick—it’s the default. Sustainability is baked into the journey, into the very design of the tourism experience.

Community-Led, State-Supported

What sets Iceland apart isn’t just its natural assets—it’s how the country chooses to use them. From the national parks to privately run eco-lodges, there is a clear pattern: decentralization, transparency, and trust. The government supports sustainable practices with incentives and public education, but decisions about tourism growth often come from the communities themselves. In Ísafjörður, I met a young guide who spoke passionately about balancing tourist interest in whale-watching with marine conservation. Her income depended on the ecosystem’s survival. So did her identity.

This alignment between governance and grassroots is a model few countries have perfected. It ensures that sustainable travel in Iceland is not just an abstract concept—it’s personal. And that’s perhaps what struck me the most: how Icelanders feel responsible not only for their own land but for their role as stewards of something much larger—an idea of the North that is clean, calm, and collectively cared for.

The Nordic Minimalist Philosophy

Traveling through Iceland teaches you restraint. The beauty is everywhere, but it doesn’t shout. Instead, it hums—through basalt cliffs, in moss-covered valleys, in the way a horse lifts its head at the distant sound of wind. This minimalism, this quiet coherence, is echoed in the country’s approach to sustainability. Lodges are built low and long, designed to blend into the horizon. Interiors are simple, functional, almost austere. There is no excess, and that feels honest.

Iceland’s version of ecotourism is not about offering everything—it’s about offering enough. Enough heat, enough light, enough connection to feel grounded without being extractive. As a traveler, you are encouraged not to consume the landscape but to coexist with it. It is a lesson in presence and humility, and one I carried with me across the globe, to the equally profound—but utterly different—world of Ladakh.

Ladakh – Sustainability Born from Necessity

High-Altitude Survival as Ecological Wisdom

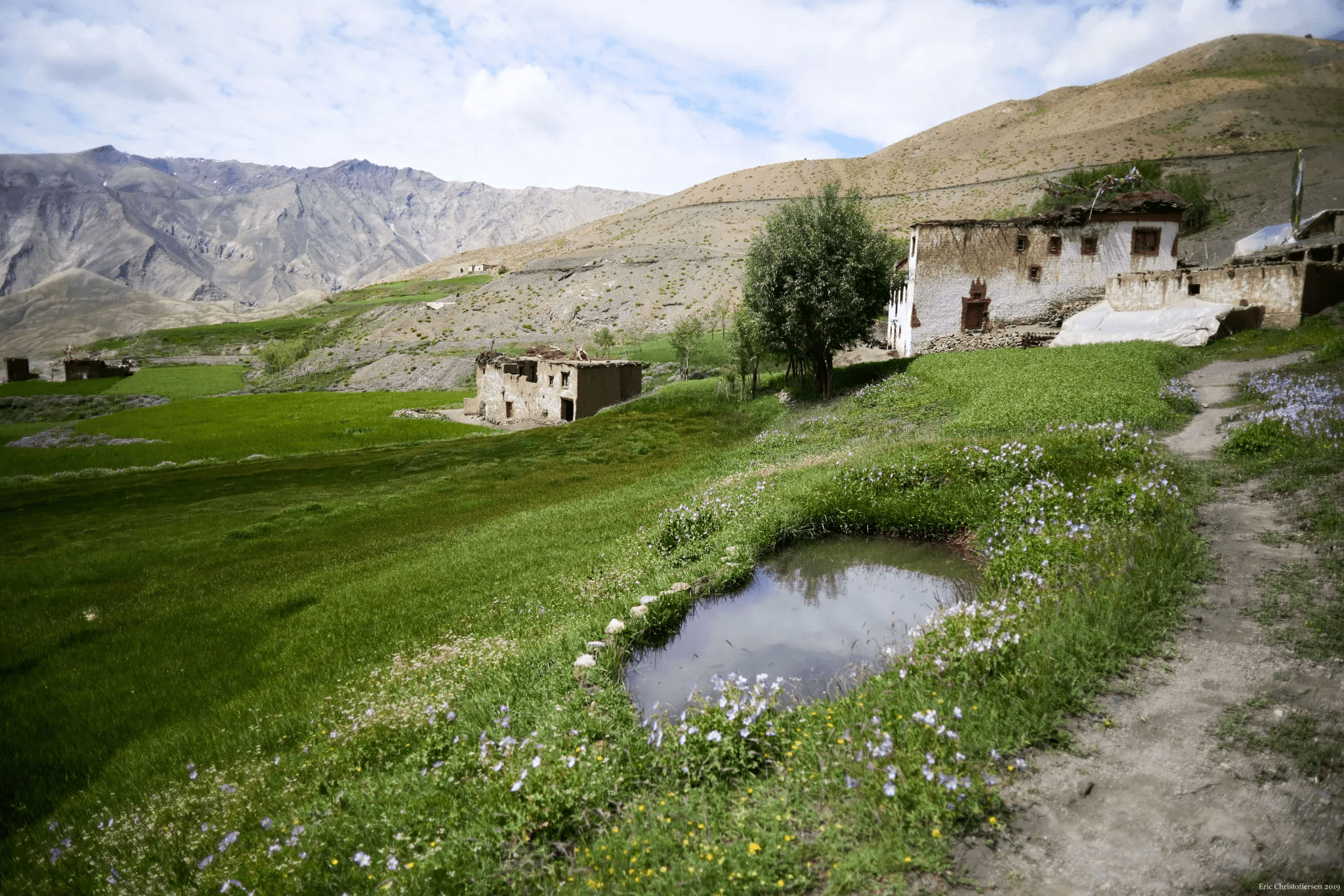

The first time I woke up in a Ladakhi village, the light was gold, not in color but in character. It came without sound, filtered through a dustless sky, bathing the mud-brick walls and silent courtyards with a purity that made everything feel earned. At over 3,500 meters above sea level, life does not flourish easily. It survives. And from that survival has emerged one of the most quietly impressive models of high-altitude ecotourism I have ever encountered.

Unlike Iceland, where ecological design is often sleek and high-tech, Ladakh’s sustainability is intimate and handmade. Villagers use dry compost toilets not because it’s fashionable, but because water is too precious to waste. Homes are built with stone, straw, and sun-baked mud, their thick walls insulating against both summer heat and winter cold. Passive solar architecture isn’t a concept discussed in seminars here—it’s embedded in tradition.

Perhaps the most astonishing innovation is the ice stupa: a man-made glacier that stores winter meltwater in towering conical formations, releasing it gradually to irrigate fields in spring. Invented by local engineer Sonam Wangchuk, these stupas are both poetic and practical—sacred shapes that save lives. I visited one near Phyang in late April, where its slow drip fed a blossoming orchard. The message was clear: adaptation can be beautiful.

Homestays, Not Hotels – The True Face of Responsible Travel

In Ladakh, I stayed not in hotels but in homes. Real homes, where grandmothers hand you a cup of butter tea before you’ve even set down your bag. These eco homestays are not polished for tourists. There are no towel swans or welcome mints—just warmth, humility, and the occasional goat bleating outside your window.

One night in Turtuk, a Balti village near the Pakistan border, I shared dinner with a family who had turned two spare rooms into guest quarters. We ate apricot stew and barley bread by solar light. They told me about the shift in weather patterns, the importance of local seeds, and their decision not to install Wi-Fi so their children would grow up connected to the land instead of a screen. It was here that I truly understood what community-based tourism means. Not a product, but a partnership.

European travelers accustomed to curated experiences may find this raw, even disorienting. But that is its gift. It demands your presence. It asks you to slow down, to relearn the rhythms of cooking, resting, and listening. In doing so, you become part of a story larger than yourself—a story of resilience that has sustained these villages for generations.

Spiritual Ecology and the Rhythm of the Land

Sustainability in Ladakh is not just technological or agricultural—it is spiritual. Each morning in the village of Alchi, I watched an elderly monk circumambulate the monastery, prayer wheel in hand, murmuring mantras with the steadiness of glacier melt. He was not performing for tourists. He was tending to balance.

This integration of ecology and spirituality is deeply moving. Fields are not plowed until rituals bless the soil. Harvests are shared communally. Festivals align with lunar rhythms. There is a quiet understanding here that the land is not owned, but borrowed. That nothing, not even water, is guaranteed.

If Iceland is a lesson in technological harmony with nature, Ladakh is a meditation on interdependence. In the stillness of these high plateaus, I felt what I can only describe as a kind of ecological humility. A sense that survival is sacred, and simplicity is strength. This, too, is sustainability—not taught in classrooms, but whispered by wind, practiced by elders, and walked into with bare feet and open hearts.

Comparative Insights – What These Lands Teach Us

Table: Ladakh vs Iceland in Sustainable Tourism

In seeking to compare Ladakh and Iceland, we must first admit: these are not parallel lands. One is Arctic, the other trans-Himalayan. One is volcanically alive, the other carved by glaciers long vanished. And yet, their approaches to sustainability converge in illuminating ways. To see this clearly, I’ve built a table—not to reduce these rich cultures to numbers, but to hold up their differences as lessons.

| Criteria | Iceland | Ladakh |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Geothermal, Hydroelectric | Solar, Ice Stupas, Micro-hydro |

| Altitude | 0–2,000 meters | 3,000–5,000 meters |

| Tourism Infrastructure | Highly developed | Minimal, community-led |

| Cultural Immersion | Moderate (optional) | High (unavoidable) |

| Tourism Type | Luxury eco-lodges, guided excursions | Village homestays, participatory living |

| Seasonal Access | Year-round | Mostly May to October |

The table makes it easy to compare. But beyond categories and metrics lies something more meaningful: a shared philosophy of presence. In both places, sustainability is not decorative—it is functional. In Iceland, the heat comes from beneath your feet. In Ladakh, the heat is stored in thick mud walls, gathered from the sun.

Contrasts in Climate, Convergences in Consciousness

While Iceland dazzles with cutting-edge design and government-led green initiatives, Ladakh impresses through ancestral techniques refined by time and necessity. Both approaches are valid. Both reveal something about how humans can live in harsh climates without harming them. But the consciousness—ah, the consciousness is where they meet.

There’s a stillness in these regions that changes you. In Iceland, it comes from the slow movement of glaciers, the pause before a geyser erupts, the silence of a black sand beach. In Ladakh, it’s in the rhythm of prayer flags, the slow simmer of lentils, the hush that follows the setting of the sun behind endless ridges. In both places, time stretches. You are asked not to fill it, but to feel it.

For the European traveler—be they eco-conscious Germans, Dutch cyclists, or French seekers of authenticity—these destinations offer two ways to reflect on what it means to live gently on this Earth. One leans toward innovation, the other toward tradition. But both invite you to listen more, consume less, and arrive with humility.

Sustainability, then, is not merely a policy or a practice. It is a mindset. Whether forged in volcanic soil or mountain stone, it comes from recognizing that what the Earth gives us is not limitless. And that gratitude—whether whispered in a monastery or built into a geothermal pipeline—is our most sustainable act.

Reflections from a First-Time Visitor to Ladakh

What Iceland Taught Me About Seeing Ladakh Clearly

When I arrived in Leh, winded from the altitude and wrapped in borrowed wool, I couldn’t help but feel like an outsider—curious, alert, but distant. It took days before my breathing found a rhythm, before my senses began to slow enough to notice the things that made Ladakh remarkable. But interestingly, it was my previous travels in Iceland that prepared me for this place in unexpected ways.

In Iceland, I had learned to observe silence—not just hear it, but enter into it. I had learned to let nature lead, not interrupt. And in Ladakh, this same ethic reappeared, but in a different dialect. The silences here are not cold and windswept, but sun-warmed and full of breath. The land doesn’t isolate—it listens. And so must we.

What stood out most was the way Ladakh lives its values quietly. There are no signs screaming “eco-friendly” or “green certified.” Yet every corner of village life speaks of conservation—because conservation isn’t something they started. It’s something they never stopped. From solar-powered homes to the way apricot pits are repurposed for winter fires, everything is used with care. This isn’t tourism with a message—it’s life with integrity.

If Iceland taught me how humans can engineer their way into harmony with nature, Ladakh reminded me that such harmony can also be inherited, protected like a lineage. For the European visitor, this is humbling. We often seek solutions through innovation. Ladakh offers something older: continuity. Not because they haven’t changed, but because they know what not to change.

The Future of Regenerative Travel is Here — and It’s High

There is a growing movement in Europe—especially among younger travelers in Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia—toward what we call “regenerative travel.” It goes beyond sustainability. It asks: How can my visit leave a place better, not just untouched? How can I listen more than I photograph, give more than I take?

Ladakh offers a unique answer. Not in a transactional way—there are no workshops labeled “give back” or curated “local immersion” programs. Instead, what you receive from Ladakh comes slowly, and only if you stay long enough to earn it. A morning spent helping in the field. An evening sharing silence in the monastery. A child handing you a dried apricot with no words exchanged. These are not Instagrammable moments. They are real.

If you’re coming from Europe with a desire to participate in the future of travel, look to Ladakh—not just as a destination, but as a mentor. It may not have the infrastructure of Iceland, but it has something rarer: a wisdom rooted in altitude, adversity, and astonishing hospitality. You don’t visit Ladakh to see the future. You visit to remember what we’ve forgotten.

Practical Tips for Eco-Conscious Travelers

Packing for Ladakh vs. Iceland

One of the most common mistakes I see among European travelers—myself once included—is assuming that all eco-destinations demand the same kind of packing. They don’t. Iceland and Ladakh may both champion sustainability, but their climates, altitudes, and infrastructures require different kinds of preparedness.

In Iceland, you’ll need waterproof layers, windproof jackets, and thermal underlayers—even in summer. The cold is wet and sudden, and trail access can shift dramatically with weather. Gloves, merino socks, and reusable crampons are smart additions for those venturing beyond Reykjavik.

Ladakh, by contrast, offers a dry cold at higher altitudes. Bring strong sun protection: SPF 50 sunscreen, UV-blocking sunglasses, and a wide-brimmed hat. Warm clothing is essential, but the emphasis here is on insulation over waterproofing. Think layered thermals, a good down jacket, and woolen socks. And no matter the season, bring a reusable water bottle with a filtration system—hydration at altitude is non-negotiable.

Above all, pack with the intention to leave no trace. Iceland’s moss fields and Ladakh’s sacred springs are delicate and slow to regenerate. Biodegradable toiletries, cloth shopping bags, and minimal packaging show respect to the ecosystems you enter.

Choosing the Right Homestay or Eco Lodge

In both regions, accommodations range from luxurious to rustic. The key for the eco-conscious traveler is not always choosing the greenest label, but the most ethically integrated experience.

In Iceland, look for lodges that are certified by the Nordic Swan Ecolabel or participate in local carbon offset programs. But also ask how they engage with nearby communities, whether their food is sourced locally, and how they manage waste. A beautifully designed eco-lodge loses meaning if it imports avocados by air.

In Ladakh, certifications are rare. Instead, authenticity speaks through behavior. Do homestay hosts serve home-grown vegetables? Do they use solar water heaters or traditional methods of keeping warm? Are you encouraged to join in the rhythms of daily life, or kept at tourist’s distance?

Remember, true eco village experiences are not found in hotel brochures—they are built in conversations, shared moments, and mutual learning. Choose places where your presence contributes, not disrupts.

Lastly, always approach these communities with humility. You are not just a visitor—you are a temporary guest in someone’s ecosystem, someone’s story. The more respectfully you travel, the richer your experience will be.

Conclusion – Between Fire and Ice, Silence and Song

There are journeys that impress you—and then there are journeys that shape you. My time between Iceland and Ladakh belongs to the latter. These two landscapes, forged by opposite elements—one by fire, the other by ice—somehow echo each other across continents. Both are wild. Both are sacred. And both ask something of you before they reveal their truth.

In Iceland, I learned to marvel at nature’s power. The explosive force of geysers, the quiet breath of glaciers, the soundless beauty of lava fields stretching into the mist. Sustainability there is systemic—calculated, precise, a triumph of green governance and technology. It made me respect what can be built when intention meets innovation.

But in Ladakh, I found something quieter—and perhaps, deeper. Here, sustainability is not constructed. It is inherited. It is in the way water is stored, food is shared, prayer is timed with the moon. There is no need to market it. It is not a feature—it is a rhythm. The song of a cold desert sung softly through apricot trees and wind-worn gompas.

For travelers from Europe, both destinations offer a mirror. In Iceland, we see the future we are trying to engineer—a future of efficiency and control. In Ladakh, we glimpse what we may have forgotten—a past of balance, of listening, of less. And in between, there is us—hovering between convenience and conscience, longing to travel not only further, but more meaningfully.

I left Ladakh with windburnt cheeks and a journal full of questions. And isn’t that the mark of a worthy destination? That it leaves you slightly changed, gently unsettled, lovingly reoriented. Between Iceland’s fire and Ladakh’s silence, I found something that felt like truth—not loud, not urgent, but lasting.

May your next journey not only show you the world, but help you hear it again.

About the Author

Originally from Utrecht, the Netherlands, she now lives on the outskirts of Cusco, Peru, where she consults for regenerative tourism projects in fragile ecosystems around the world.

At 35, she brings over a decade of experience working with indigenous communities, climate scientists, and ethical travel startups. Her writing blends academic insight with emotional depth—offering readers a lens that is both analytical and deeply human.

She arrived in Ladakh for the first time this year, and her perspective is refreshingly sharp. As a newcomer, she brings the kind of clarity that only unfamiliar eyes can offer—constantly comparing, questioning, and connecting this remote Himalayan region to broader global narratives.

Whether she is writing about ice stupas in Ladakh or geothermal lodges in Iceland, her work is driven by one essential question: How can we travel in a way that leaves places more whole, not more hollow?