Journey Across the Zanskar River

The River That Becomes a Road

At dawn, the air is razor-sharp, cutting through the wool layers wrapped around Tenzing’s small frame. He stands outside his family’s home in Padum, Zanskar Valley, shifting his weight from foot to foot to keep warm. In the distance, beyond the smoke curling from the low-roofed houses, the river waits—silent, frozen, treacherous.

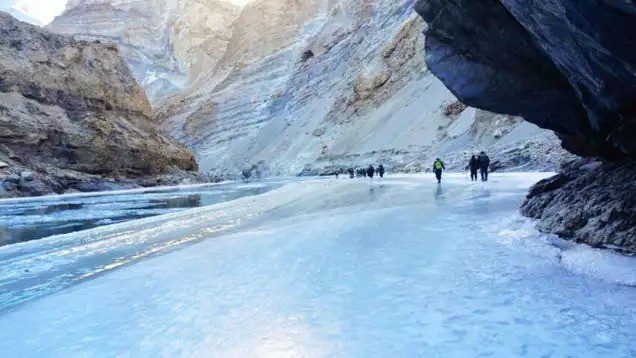

For the past three months, the Zanskar River has been his village’s only road. When the last motorable path was swallowed by snow in early November, it left the people of Zanskar with only one option: the ice. In the heart of winter, the river freezes into an unsteady bridge of blue and white, a lifeline that connects Padum to the outside world. The people call it Chadar—the sheet. And this year, for the first time, it will take Tenzing away from home.

His father, Namgyal, stands beside him, his breath visible in the morning air. He is a man of few words, his face carved by years of mountain winds and the unforgiving cold. He tightens the straps on his pack, adjusting the weight of supplies—a few dried apricots, tsampa, yak butter, and a thick woolen shawl. Then, without ceremony, he nods. It is time.

Tenzing glances back at his mother, who stands in the doorway, arms folded beneath her woolen goncha. Her face is unreadable, but her fingers twitch at her side. She does not cry. It is not the Ladakhi way. Instead, she steps forward, presses a small pouch into Tenzing’s hands, and whispers, “For the road.” He does not look inside. He knows it holds prayers, protection, and a piece of home.

The journey ahead will take more than a week. A hundred kilometers of ice, cracked and shifting beneath their feet, with nothing but the cliffs towering on either side. The frozen river is unpredictable; some days, the ice will be thick enough to hold a caravan, other days, a single misstep could send a traveler plunging into the black water beneath. But there is no alternative. Schools in Leh are reopening, and education is a promise too important to break.

Namgyal begins walking. Tenzing follows.

The river has become a road, and the classroom is waiting.

When the Ice Forms, the Journey Begins

The ice is alive. It groans beneath their feet, shifting like something ancient and restless. Tenzing’s breath comes in small, sharp clouds as he follows his father’s steady footsteps, each step deliberate, tested, cautious. The Chadar is never the same from one day to the next. One moment, the ice is solid, smooth as glass. The next, it fractures, revealing a river still moving beneath, dark and unfathomable.

The first few kilometers feel familiar. The towering cliffs of the Zanskar Gorge stretch endlessly on either side, casting deep shadows over the river. During summer, this passage is impassable, a furious torrent of glacial meltwater that isolates Padum from the outside world. But in winter, the river changes. It submits—at least for a while—allowing men, women, and children to cross. Some travel for trade, some to visit family, and some, like Tenzing, leave for school, carrying the hopes of their village with them.

His boots are wrapped in yak wool, designed to grip the ice without slipping, but even so, he stumbles. Namgyal stops, waiting without a word. Tenzing knows better than to complain. In the mountains, in the cold, words are wasted. Every step matters. Every movement is measured.

They walk in silence, the only sounds the crunch of ice and the occasional splash where the river refuses to freeze. In places where the ice is too thin, they climb along the jagged cliffs, grasping at frozen rock, their fingers stiff in the cold. This is the way it has always been.

As midday approaches, they stop at a bend in the river where the sun reaches down, throwing light onto the ice. Here, they rest. Namgyal unrolls a bundle of tsampa and dried meat, passing a handful to Tenzing. He eats without speaking, chewing slowly, staring at the river. It stretches ahead like a path to another world—one he has never known, one he is not yet sure he wants to see.

A deep crack splits the silence. Tenzing’s stomach tightens. He looks at his father, waiting for reassurance, but Namgyal only nods toward the ice. “Keep moving,” he says.

Tenzing swallows hard, adjusts the strap on his bag, and follows.

The ice is alive. And so is he.

The Boy Who Must Walk the Ice

The cold is a living thing. It seeps into Tenzing’s bones, nestles in his fingertips, coils around his breath. The sun, pale and distant, offers no warmth. Each step feels heavier, his body slow and stiff beneath layers of wool. But the journey is only just beginning.

Padum is behind them now, a distant memory swallowed by the frozen canyon walls. Ahead, the Chadar stretches endlessly, a cracked and shifting highway of ice leading toward Leh. The river will decide whether they move forward or not. If the ice holds, they walk. If it breaks, they climb the cliffs, pressing their bodies against sheer rock, balancing on ledges no wider than a footprint. There is no other way.

Tenzing is the youngest among the travelers that day. A handful of men walk ahead of them, carrying supplies—flour, rice, salt—wrapped in cloth bundles. Some are traders, some are making the trek for the first time in years, their faces unreadable beneath scarves and thick woolen hats. They do not speak to one another. Conversation is an indulgence the cold does not allow.

His father walks with quiet confidence, his staff tapping against the ice, testing its strength before each step. Tenzing mimics him, careful, deliberate. He does not want to slow them down. This journey is a test—not just of endurance, but of something deeper. It is proof that he is ready.

He feels the weight of expectation pressing against his chest. His mother’s parting words linger in his mind. “For the road.” She had pressed the small pouch into his hands before he left, her fingers rough and warm against his own. Now, he reaches inside, feeling the smooth beads of a mala, a tiny scrap of fabric wrapped around dried juniper leaves. Protection. A piece of home.

A sharp gust of wind rips through the canyon, howling between the cliffs. The ice shifts beneath them, groaning like something restless and alive. The men ahead pause. No one moves.

Tenzing holds his breath. This is the moment his father warned him about—the moment when the river reminds them that it is not a road at all.

The Chadar decides who passes. And who does not.

A Classroom Beyond the Mountains

The Unseen Struggles of Zanskar’s Children

For Tenzing, school is not just a place—it is a distant promise. A building beyond the mountains, beyond the frozen river, where letters take shape on pages and numbers are whispered in the soft scratch of chalk on slate. But to reach it, he must first survive the journey.

The cold gnaws at his hands, numbing his fingers through the woolen gloves. The wind funnels through the canyon, pressing against his small frame, stealing warmth from his skin. He clenches his fists, tucks them deep into his sleeves, and keeps walking.

His father had told him once, years ago, about the importance of education. “The river is a path,” Namgyal had said, his voice as steady as the ice beneath them. “But knowledge is the bridge you will build yourself.” In Padum, the old monks still teach in the monasteries, their voices weaving through the winter air in rhythmic chants. But beyond Zanskar, in Leh, there are schools where books are more than prayer texts, where science and mathematics unfold like stories.

Not every child in Zanskar makes the journey. Some stay behind, their futures shaped by the land, tending to yaks, collecting firewood, waiting for spring to bring traders from the outside world. For those who leave, the frozen river is a rite of passage. It is a test of endurance, patience, and faith.

Tenzing knows what awaits him at the end of the ice—a schoolyard filled with voices, a room where the walls hold warmth, a world where he will learn more than the mountains have already taught him. But first, he must keep moving.

The Whispering Ice and the Dangers Beneath

The river is never silent. Even in the stillest moments, the ice murmurs beneath their feet, shifting, settling, warning. The Chadar is not a road in the way a road should be. It is a living thing—changing with each hour, each temperature drop, each breath of wind that brushes against its surface.

Tenzing listens. His father had told him that the ice speaks if one knows how to hear it. A deep crack, sharp and sudden, means danger—a place where the river beneath is restless, where the ice may not hold. A low groan, stretched and slow, means the surface is adjusting but not breaking. And silence—true silence—is the most dangerous of all. Silence means thin ice. Silence means uncertainty.

Ahead, a section of the river is unfrozen, a gash of dark water winding between the ice. The men pause, exchanging looks. Some test the edges with their staffs, tapping lightly, listening. Namgyal studies the surface, then looks up at the cliffs. “We climb,” he says.

Tenzing swallows hard. He has seen his father scale these cliffs before, moving with the ease of someone who has spent a lifetime in the mountains. But for him, this is new. His hands tighten into fists. There is no turning back.

His father moves first, gripping the frozen rock, finding footholds where none seem to exist. The other men follow, their movements practiced, deliberate. Then it is Tenzing’s turn. He exhales, places his hands on the rock, and begins to climb.

The frozen classroom is teaching its first lesson: fear is a luxury. There is only forward.

A Father’s Footsteps, A Son’s Resolve

The Lessons Taught in Silence

The wind carries no mercy. It rushes through the gorge, pressing against their backs as they inch along the frozen river’s edge. The climb had been difficult—Tenzing’s fingers, stiff with cold, still ache from gripping the ice-slick rock. But they had made it. The river continues beneath them, winding through the deep valley, endless and unmoved.

His father has not spoken much since they left Padum. But Namgyal is not a man of unnecessary words. He teaches through action, through presence. His steps are precise, each one measured. He moves with the knowledge of someone who has walked this path many times before, who has learned to listen to the river, to the wind, to the shifting ice beneath his feet.

Tenzing follows, placing his boots exactly where his father’s have been, trusting that the ice will hold where Namgyal has deemed it safe. The silence between them is not empty. It is filled with understanding, with lessons unspoken but deeply known.

The boy watches his father closely—the way he shifts his weight when testing an uncertain stretch of ice, the way he reads the color of the river’s surface, knowing when it is too thin to trust. This is knowledge not found in books, not taught in schoolrooms, but passed from one generation to the next. In this frozen landscape, survival is an inherited wisdom.

For a moment, as they walk, Tenzing lets himself wonder about the world beyond the ice. He has heard stories of Leh—of buildings taller than any in Padum, of shops filled with books, of classrooms where the cold does not bite at your fingers while writing. It seems impossible. And yet, it waits for him, beyond the river, beyond the days of walking. A place where learning does not come at the cost of frozen hands and aching limbs.

He glances at his father, walking a few steps ahead. Namgyal had never been to school. His lessons had been learned in the mountains, in the winters spent herding, in the long nights tending to the fire. And yet, he had chosen this path for his son—to walk the river, to cross into a world he himself had never known.

Tenzing grips the strap of his bag tighter. He will not fail him.

When the Ice Breaks

The ice does not break suddenly. It warns first—a sharp, splintering sound, like wood snapping beneath weight. Then, the crack spreads, a deep, haunting sound that echoes through the gorge.

Tenzing stops. The men ahead of them freeze in place. Even the wind seems to pause.

Namgyal lifts a hand. No one moves.

The ice beneath them groans. A fissure runs along its surface, stretching toward the center of the river where the water still moves, black and bottomless. Another crack forms near the edge, spreading like a jagged scar.

Tenzing does not breathe. His heartbeat is a drum in his ears.

Namgyal takes a step back, slowly, carefully. The others do the same. They retreat toward firmer ground, their movements deliberate, their bodies tense.

The river is reminding them of its power. The Chadar is not a road, not truly. It is a negotiation, a fragile agreement between nature and man. Today, it is willing to let them pass. But only if they listen.

Namgyal waits, watching the ice. After a long moment, he nods. They will take the long way—climbing the rocks, avoiding the weakened surface. It will add hours to their journey, but time is a small price to pay for safety.

Tenzing exhales. He did not realize he had been holding his breath.

His father meets his gaze, nods once, then turns to lead the way.

The lesson is clear. The ice does not forgive arrogance. The river decides who crosses, and today, it has allowed them to continue.

The Frozen Classroom and the Promise of Spring

The Arrival in Leh: A World of Warmth and Books

The final stretch of the journey is the longest. Not in distance, but in weight—the weight of exhaustion, of frozen limbs, of days spent moving through ice and wind. Each step feels heavier now, as if the ice itself is asking for more effort, more willpower. Tenzing’s legs ache, his breath comes in slow, measured puffs. But Leh is close.

The canyon walls begin to open, widening into a valley where the river slows. The ice is thicker here, more stable. The wind carries different sounds—faint voices, the distant clang of metal, the echo of life beyond the mountains. And then, at last, there it is: Leh, a cluster of whitewashed buildings rising from the frost, their flat roofs dusted with snow. Smoke curls from chimneys, the scent of burning wood mixing with the crisp winter air.

Tenzing feels something tighten in his chest. This place is nothing like Padum. It hums with movement, with noise, with a pace faster than the quiet rhythm of his village. There are cars here, market stalls, people dressed in layers that seem thinner than the heavy woolen gonchas of Zanskar. And then there is the school—a low, yellow building standing firm against the winter.

Namgyal places a firm hand on his son’s shoulder. “This is your place now,” he says. His voice is steady, but Tenzing knows this is not easy for him. A man who has never needed books, who has only known the wisdom of mountains, is leaving his son in a world he does not fully understand.

The schoolyard is filled with boys and girls, their cheeks flushed from the cold, their laughter rising in bursts of steam. A bell rings, calling them inside. Tenzing grips the straps of his bag tighter. He will enter that building, he will sit in a room where numbers and letters take shape, where he will learn to read the world in ways his father never could.

His father does not stay. There is no need for a long farewell. He simply nods, the way he always does, and turns back toward the river. The ice will be waiting.

The Long Wait for the Ice to Return

The river will freeze again when it is time to come home. When the last snows of winter settle, when the cold returns with full force, the Chadar will form once more, stretching across the valley like a path carved in ice. And when that happens, Namgyal will make the journey again.

Tenzing knows this. It is part of the rhythm of life in Zanskar—the leaving and the returning, the waiting and the walking. He will sit in a warm classroom, filling pages with words, while his father tends to the winter in Padum. And when the ice is thick enough, when the river is ready, he will walk the Chadar again.

For now, though, he stays. He listens as a teacher begins a lesson, as words fill the room, as the warmth of learning pushes back against the cold. And far away, beyond the valley, beyond the walls of the school, the frozen river waits—silent, patient, knowing that one day, it will carry him home.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor is a journalist and columnist specializing in narratives that explore the intersection of human resilience and extreme environments. With a keen eye for detail and a deep appreciation for the untold stories of remote communities, his work captures the raw beauty and challenges of life in some of the world’s most isolated regions.

O’Connor has spent years documenting journeys across the Himalayas, the Arctic, and other extreme landscapes, bringing to life the voices of those who navigate these unforgiving terrains. His writing blends immersive storytelling with a journalist’s precision, shedding light on the cultural and personal struggles that shape these journeys.

His columns focus on the human spirit’s ability to adapt, endure, and triumph against the backdrop of nature’s harshest conditions. Whether following a schoolboy’s perilous trek across a frozen river or uncovering the fading traditions of a mountain village, O’Connor’s work resonates with readers seeking more than just adventure—he offers a window into lives rarely seen, yet deeply significant.

Through his storytelling, he not only documents survival but also preserves the narratives of people whose lives are shaped by ice, wind, and altitude. His work is a testament to the quiet strength of those who live beyond the edges of maps, reminding us that every journey—no matter how treacherous—carries a story worth telling.