Where the River Remembers Older Stories

By Declan P. O’Connor

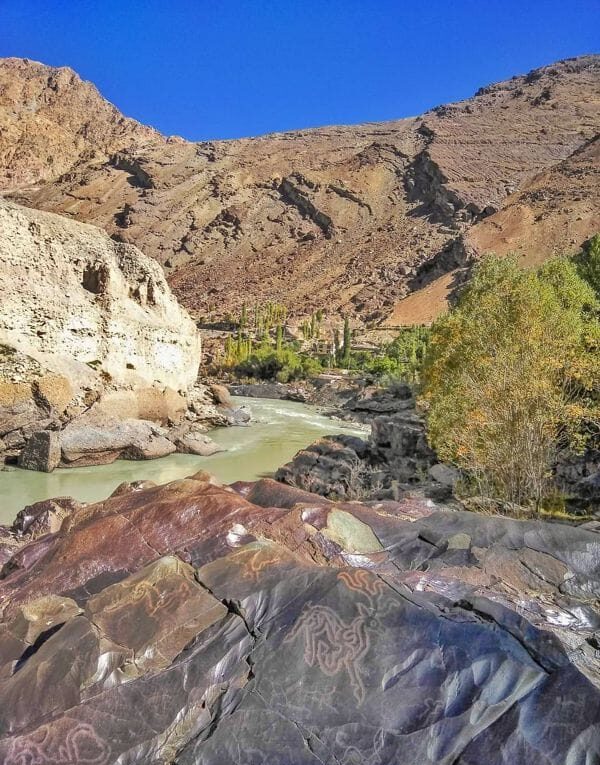

I. Opening: Along the Quiet Bend of the Lower Indus

The corridor where silence carries culture

There are stretches of the Himalaya that announce themselves with snow peaks and prayer flags, and there are others that must be listened to before they can be seen. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor belongs firmly to the second category. Driving west from Leh, the road holds to the river as if it were a rail, tracing a deepening gorge where the Indus has spent millennia cutting through rock and assumption alike. This is not a landscape that flatters the visitor with instant drama. Instead, the first things you notice are small: an irrigation channel disappearing into stone, a line of willow trees clinging to a ledge above the torrent, a cluster of whitewashed houses gathered around a barley field the size of a pocket handkerchief.

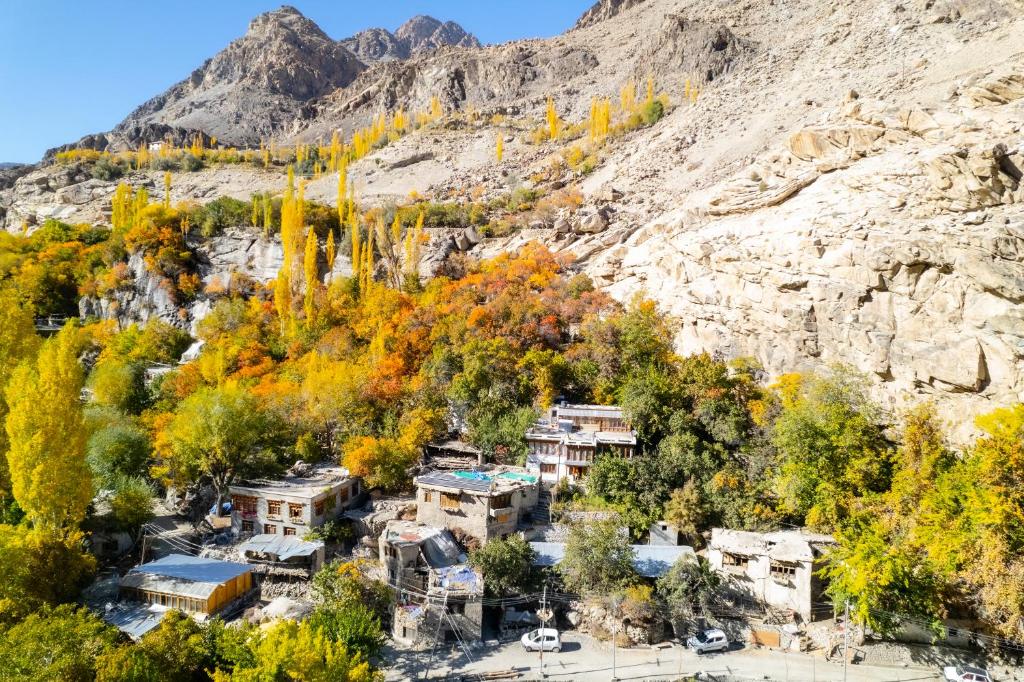

For European travelers used to the Alps or the Dolomites, the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is disorienting in a gentler way. It is high, but not expressionistic; beautiful, but rarely symmetrical. The mountains rise like walls rather than peaks, and the life of the valley hugs the river in thin, green scripts. Each village – Takmachik, Domkhar, Skurbuchan, Achinathang, Darchik, Garkone, Biamah, Dha, Hanu, Batalik – seems to have been negotiated from the rock rather than granted by it. To move along this corridor is to move through a sequence of quiet compromises between water, gravity and human patience, stitched together by a road that sometimes feels provisional, as if it might at any point decide to slide back toward the river that allowed it to exist.

How the Brokpa identity lives in fields, orchards, and faces

The villages of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor are best known, in the fragmented vocabulary of travel writing, for the people who inhabit them. The Brokpa have appeared in coffee-table books and anthropological studies, shorthand for a community that has preserved particular dress, language and ritual forms along this river. Yet to arrive here expecting only ethnographic spectacle is to miss the deeper story. Brokpa identity is not confined to costume or festival; it is inscribed into terraced fields, apricot orchards, stone walls and the rhythm of irrigation days. You see it in the way water is shared, in how paths curve around sacred trees, in the patient labour that keeps barley, buckwheat and vegetables rooted in such improbable soil.

In the lanes of Darchik or Garkone, faces and flowers do indeed catch the foreign eye, but they belong to a wider choreography that includes goats on narrow ledges, children chasing each other along the irrigation channels, women returning from the fields with sickles tucked under their arms. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is not a museum of a “vanishing tribe”; it is a living, sometimes weary, often resilient rural world navigating change. Solar panels glint beside prayer flags; school uniforms brush past traditional headgear. The continuity lies less in an unbroken past than in a stubborn insistence on farming these slopes, season after season, even as the outside world keeps expanding the menu of imagined alternatives.

II. Takmachik — The Threshold Village

Where sustainable farming becomes a worldview

Takmachik is often described as a model of sustainable tourism, but before it was a case study it was simply a village trying to survive on a narrow fold of arable land between cliff and river. Arriving there, you notice first the ordinariness of the place: children on their way to school, a shop selling biscuits and mobile top-ups, a prayer wheel waiting to be turned by hands on their way to somewhere else. Only slowly do you realise how carefully the community has tried to shape its relationship with visitors. Homestays are not an afterthought; they are an extension of household life, where apricot kernels are cracked in the courtyard while conversations about weather, migration and education unfold over butter tea and bread baked the same morning.

In Takmachik, the language of “eco” and “sustainable” has not arrived as a marketing slogan pasted onto a generic trekking route. It emerges from a simple calculation: the fields, orchards and pastures that feed the village cannot be scaled up infinitely, but curiosity from outside can. The people of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor know better than most what happens when an ecosystem is pushed to the edge. So Takmachik has become a threshold of another kind – a place where European travelers can experiment with a slower, more attentive form of presence, and where the village can test, gingerly, how much of its privacy it is willing to place on the table alongside the apricot jam and homegrown vegetables.

A place where the Indus introduces the traveler gently

Every corridor needs a doorway, and Takmachik plays that role with a kind of understated grace. For those coming from Leh, the village offers the first opportunity to step off the road and onto paths that know nothing of asphalt or itinerary. The Indus flows below, sometimes visible, sometimes obscured by rock, and the sound of the river becomes a background presence, like a conversation happening in the next room. Paths wind between houses, spill into fields, and rise toward hillside shrines that look back over the valley with a wary, custodial gaze. The altitude is high enough to thin the air but low enough to allow barley and vegetables to grow, and that balance makes Takmachik feel unexpectedly hospitable, especially for those just beginning to adapt to the elevation of Ladakh.

For European visitors attuned to dramatic introductions – airport runways framed by snow peaks, postcard monasteries perched on obvious ridges – the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor makes a different proposition. In Takmachik, there is no singular “sight” that absorbs all attention. Instead, the village itself becomes the object of observation: how many walls must be repaired before sowing, how long the line of women at the communal water point, which field receives irrigation first after a dry spell. To walk here is to be introduced not to a monument, but to a pattern of life that will echo, with variations, all the way to Batalik. The corridor begins, quietly, with a village that has decided it would rather be known for its farming than for the number of rooms it can offer strangers.

III. Domkhar — Stone, Light, and Human Scale

Villages that cling to cliffs and memory

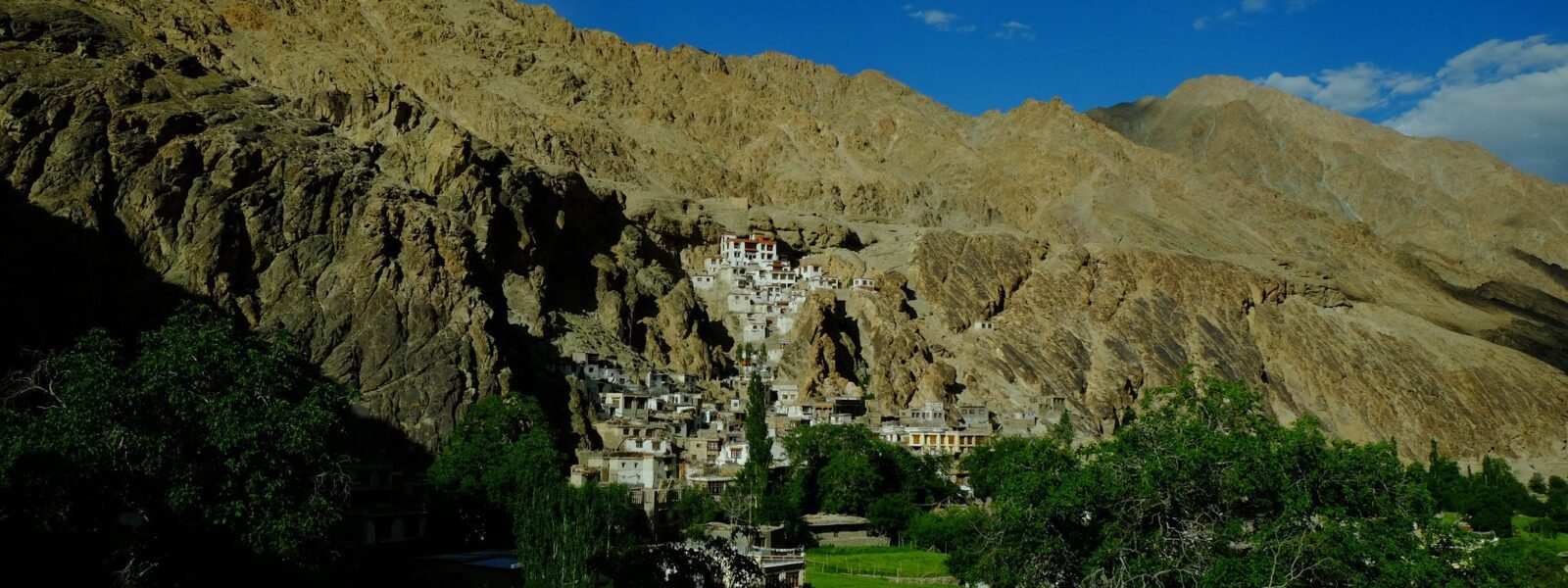

West of Takmachik, the road keeps following the Indus as if reluctant to admit there might be any other logic to movement in such a narrow world. When you reach Domkhar, the mountains seem to close in, shouldering the river into a more tightly defined channel. The houses of the village appear to cling directly to the rock, stacked in a vertical grammar that makes sense only when you begin to walk the lanes yourself. It is easy, from the car window, to mistake Domkhar for a set of stone terraces pinned to a cliff; on foot, you discover that it is a three-dimensional debate with gravity, hospitality and memory, conducted in alleys barely wide enough for a laden donkey.

The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is full of such negotiations, but in Domkhar they are especially visible. Stone is everywhere – in the retaining walls, the steps, the tiny courtyards, the prayer walls and the rough boundary markers that tell you when a path becomes a field. It is tempting to romanticise this immediacy, to turn it into evidence of rootedness and permanence. Yet talk long enough with an elder leaning against one of these walls and you will hear different tone: stories of years when the river froze late, when the barley failed, when sons left for the army or for city jobs that would never bring them back. Domkhar clings, yes, but it clings not only to the cliff; it also clings to an idea that life in this village is still worth the effort that its geography demands.

The intimacy of barley fields beneath impossible rock formations

Perhaps the most surprising element of Domkhar is not its stone but its softness. Just beyond the tight cluster of houses, barley fields spread out like small carpets laid carefully wherever the land relaxes enough to allow a little soil to settle. Above them, rock formations rear up in improbable shapes, eroded into towers, fins and ledges that look as if they might detach themselves and walk away when no one is looking. This juxtaposition – intimate fields under theatrical geology – is part of what defines the visual character of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor. It is a landscape where cultivation is always dwarfed but never entirely overshadowed, and where beauty depends on the stubborn insistence of green against stone.

Walk along the irrigation channels in the late afternoon, when the sun slides behind the upper ridge and the valley fills with a soft, almost metallic light, and you begin to feel the proportions of Domkhar in your own body. Distances that looked negligible on the roadside become meaningful when climbed on foot; a short detour to a shrine turns into twenty minutes of steady breathing. For visitors from Europe, where the countryside is often understood through the convenience of car parks and waymarked trails, there is something quietly humbling about this intimacy. The fields are not scenic foregrounds to the mountains; they are the whole point. The rock formations may command the camera, but it is the barley that commands the calendar.

IV. Skurbuchan — The Middle Kingdom of the Corridor

A village large enough to gather stories

Skurbuchan sits roughly in the middle of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, and it has the feeling of a place where stories pause to collect themselves. Larger than Takmachik or Domkhar, with more visible infrastructure and a wider spread of houses, it serves as a local centre for schools, small shops and administrative routines that rarely find their way into travel writing. Yet it is precisely this scale that makes Skurbuchan such an instructive chapter in the corridor’s unfolding. Here, the tension between continuity and change is not abstract; it plays out in the decision to send a child to boarding school in Leh, to accept a road-widening scheme, to turn part of a family home into a guest room with its own bathroom and solar water heater.

The lanes of Skurbuchan weave through houses that seem older than they are, their walls thick with repeated repairs. On the slope above the village, orchards and fields arrange themselves in careful geometry, each terrace assigned to a household, each tree carrying a history of grafting, pruning and patience. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is sometimes described as remote, but in Skurbuchan you are reminded that remoteness can be a relative concept. Mobile reception is patchy but present; young people know as much about film and football as their peers elsewhere. What is fragile is not information but the fabric of a village where everyone knows who irrigated which field on which day, and where the absence of a single family at a festival can still be felt as a disturbance in the pattern.

Festivals, ordinary life, and the geometry of fields

Skurbuchan Monastery, perched on a ridge above the village, provides the kind of vantage point that European travelers often imagine when they think of the Himalaya. From its courtyard, the village below appears as an intricate diagram of human persistence – white cubes of houses, green rectangles of fields, the grey ribbon of the road, and beyond it all the steady, unsentimental presence of the Indus. Festivals here draw people from the surrounding villages of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, bringing together Brokpa families and others in a mixture of ritual, socialising and quiet observation. Mask dances unfold in sequences that feel both rehearsed and slightly improvised, while older women watch from shaded corners, evaluating not the tourists but the younger generation’s fidelity to steps and songs.

Yet if you stay beyond festival days, Skurbuchan reveals a slower choreography. Before sunrise, herders lead animals towards higher grazing; later in the morning, children navigate the steep paths to school, their satchels bouncing against their backs. In the fields, the geometry that looked so neat from the monastery becomes a matter of mud, stones and exact timing. Irrigation is shared according to agreements that long predate smartphones, enforced by a combination of memory, gossip and the occasional argument. For visitors moving through the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, Skurbuchan offers a chance to see how ritual time and agricultural time overlap without fully merging. The monastery bells may mark auspicious days, but it is the arrival of water at the top of a terrace that determines when the day’s true work begins.

V. Achinathang — Where the River Narrowly Breathes

A quieter bend of the Indus

If Skurbuchan feels like a centre, Achinathang feels like a parenthesis. The road, still shadowing the river, dips and rises through rock cuttings that seem almost embarrassed by their intrusion, and then suddenly there is a widening, a cluster of fields, a few dozen houses anchored to the slope. Achinathang does not announce itself with a monastery silhouette or a particularly dramatic bend in the Indus. Its presence is more modest: a sequence of poplar trees, the outline of an old watchtower, the scrape of a hoe on dry soil. For the traveler moving along the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, this is a place where the narrative of movement slows almost without permission, as if the landscape were insisting on a paragraph break.

Here, the river seems to take a slightly deeper breath. The gorge eases, just enough to allow for a wider apron of cultivation, and the village has filled that space with orchards and fields that look almost level compared to the steeper terraces elsewhere. For European visitors, the temptation is to see Achinathang as a “rest stop” between more obviously photogenic villages. But to experience it that way is to miss the quiet argument it makes about scale and sufficiency. Life here is neither spectacular nor marginal; it is simply calibrated to the amount of flat land available, the reach of the irrigation channels and the patience of those willing to live a long way from any large market, yet close to everything they actually need on a daily basis.

Apricot trees as an archive of human settlement

If you want to understand Achinathang, look not first at the houses but at the apricot trees. They have a way of growing exactly where someone once decided to take a risk on water and soil, marking locations where a family believed it could survive. In the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, apricot orchards perform the work that street maps do in European cities: they reveal where life has clustered, where paths intersect, where risk and reward have historically aligned. Each old trunk, gnarled and hollow, is a kind of living archive, recording decades of pruning, storms, late frosts and generous harvests.

In Achinathang, these trees occupy a middle space between wild and domesticated. They are planted, certainly, but once established they seem to belong as much to the village as to any particular household. Children climb them without asking; travellers rest beneath their shade; birds treat them as highways. During harvest, blue tarpaulins spread under their branches, and the village fills with the sound of fruit hitting fabric, a soft percussion that signals both income and winter calories. For visitors from temperate Europe, there is something familiar in this seasonal rhythm and something profoundly different in its precariousness. The margin for failure is narrower here; a single late frost can undo months of careful anticipation. To walk among the apricot trees is to sense how much of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor rests on the fragile generosity of a short growing season.

VI. Darchik — A Village of Faces and Flowers

The vibrant heart of Brokpa heritage

By the time you reach Darchik, the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor has already offered several lessons in scale, patience and attention. Yet it is here that many visitors feel they have reached some kind of emblematic centre, a place where the abstract idea of “Brokpa culture” becomes unmistakably embodied. Darchik clings to the slope above the river in a dense tangle of houses, paths and terraces, more vertical than horizontal. Stepping out of the car, you feel immediately that the village is watching you with the same intensity with which you are watching it. Not suspicious, exactly, but interested in how you will behave in a place that has become both a home and a stage.

It is easy to reduce Darchik to its iconography: elaborate headdresses decorated with flowers, coins and shells; heavy jewellery; festival costumes that have travelled widely in photographic form. But treat these only as exotic surfaces and you will find the village withdrawing from you, retreating into the private business of fieldwork, child-rearing and household chores. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor cannot be understood through images alone; it requires listening for the stories that those images conceal. In Darchik, that often means hearing about land disputes, education choices, and the subtle ways in which tourism has both opened possibilities and complicated internal hierarchies. The vibrant displays of heritage here are not static; they are active negotiations over what to preserve, what to let go, and how to remain legible to oneself while becoming more and more legible to strangers.

Adornment, identity, and the texture of lineage

Spend a day in Darchik without a camera in your hand and you begin to notice how adornment functions as a language rather than a costume. The flowers that women wear in their headdresses are not random; they follow seasonal availability, personal preference and sometimes subtle codes of status or mood. Jewellery carries stories of marriage, inheritance and exchange. Children learn early how to handle these objects, when to wear them and when to set them aside for fieldwork. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is often described as a place where “traditions survive,” but that phrase can obscure the active work required to keep such practices meaningful. Adornment here is not a relic; it is a live wire connecting lineage, land and the present moment.

For European travelers accustomed to museums where objects are labelled, contextualised and safely behind glass, the immediacy of this living archive can be disorienting. A necklace admired during a conversation might later reappear on a different relative; a headdress photographed in festival light might be drying the next morning on a courtyard wall. The texture of lineage in Darchik is not just genealogical; it is tactile, weighty, occasionally cumbersome. It reminds you that identity, in the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, is less a fixed costume than a set of responsibilities borne, quite literally, on the body. To be “from here” is to know not only the history of your family, but the exact shelf where the ancestral jewellery is kept and the right moment in the year to bring it back into the light.

VII. Garkone — A Garden in the Gorge

Walking a path lined with irrigation channels and memory

If Darchik feels like an amphitheatre, Garkone feels like a garden designed by a patient hydraulic engineer. The path through the village follows irrigation channels that branch, twist and reconcile like sentences written by someone who cannot quite decide where to end. Water here is not simply a resource; it is an organising principle. It tells you where the houses can stand, where the fields must begin, where the paths may cross, and where they must defer. As you move through Garkone, the sound of water accompanies you, sometimes loud and insistent, sometimes reduced to a thin, secretive thread along the edge of a terrace.

The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor depends everywhere on such channels, but in Garkone their presence feels particularly intimate. People greet each other not only with words but with small adjustments to shared infrastructure – a stone moved, a gate opened, a leak patched with a handful of mud. For a visitor, this can be an education in a kind of politics that rarely appears in news reports but decides, quietly, who eats well and who struggles. Memory is stored here not in archives but in recollections of who contributed labour to which channel on which year, who respected the irrigation schedule and who did not. Walking through Garkone, you sense that every path is a compromise, every shortcut a story about trust either extended or withdrawn.

How a remote village becomes a cultural center

From a mapmaker’s perspective, Garkone is remote: a small settlement in a gorge, far from major markets, pressed between river and cliff. Yet in the cultural geography of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, it functions as a centre of gravity. Festivals here draw participants from neighbouring villages; songs and stories circulate widely, carrying Garkone’s refrains far beyond its physical boundaries. Guests arrive not only from Leh or Kargil but from Europe, following rumours of a village where heritage is both fiercely guarded and reluctantly displayed. Homestays have multiplied, and so have conversations about what exactly is being offered and on whose terms.

One elder in Garkone described the village to me, with a half-smile, as “a garden with too many visitors.” The remark was not hostile so much as diagnostic. The very qualities that have made this place a cultural reference point – its tapestry of orchards, its intricate water systems, its strong sense of collective identity – also make it vulnerable to being turned into a backdrop for other people’s stories. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor stands at an uneasy intersection between being seen and being understood, and Garkone embodies that tension vividly. It reminds travelers that to visit a “cultural centre” is not to consume an experience, but to enter, briefly and imperfectly, into ongoing debates about how a community wishes to present itself to the world.

VIII. Biamah — The Small Pause Between Worlds

A place that feels like a comma in the corridor

After the intensity of Darchik and Garkone, Biamah arrives like a soft, necessary pause. The road continues to follow the Indus, but the valley seems to open just enough to invite a slower exhale. Houses are fewer, fields more widely spaced, the general atmosphere less performative. Biamah is not absent from the story of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor; it simply refuses to insist on its importance. It functions, instead, like a comma in a long sentence – a small breath that changes the rhythm without altering the direction.

For travelers, this can be a relief. There is time here to walk without constantly negotiating between the impulse to photograph and the obligation to greet. Paths lead gently through fields where the concerns are stubbornly local: the quality of the seed, the timing of the next irrigation, the health of a particular calf. Homestays exist, but they feel more like extended family arrangements than like micro-hotels. For European visitors accustomed to itineraries that must justify every stop with a list of attractions, Biamah poses a quiet question: Can a place be worth your time simply because it allows you to feel the gradualness of the corridor more clearly?

Evening light, quiet homesteads, and slow geography

If Biamah has a speciality, it is evening light. As the sun drops behind the surrounding ridges, the slopes catch the last colour in irregular patches, leaving some houses already in shadow while others still gleam briefly. Smoke rises from kitchen roofs; small groups linger outside doorways, finishing conversations or simply sharing silence. The Indus, now a familiar companion along the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, seems to deepen in tone rather than in volume, turning from bright steel to something closer to ink. It is a good place to sit on a wall and allow your eyes to adjust to slower movements.

Geography here does not shout. It suggests. The lines of the terraces, the angle of the path between two houses, the particular bend of the river at the edge of the fields – all of these begin to register as part of a pattern that extends backward and forward. In Biamah, you are close enough to Dha and Hanu to sense their pull, and not so far from Batalik that the word “border” seems abstract. Yet the village itself appears content to hold its place in the corridor as a minor but indispensable note. It teaches, gently, that not every stop on a journey has to be climactic in order to be decisive.

IX. Dha — The Village That Visitors Speak of First

A symbolic home of Brokpa identity

Ask travelers in Leh or Kargil what they remember most vividly about the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, and the name “Dha” surfaces early and often. The village has acquired a symbolic weight that exceeds its physical size, standing in for a whole constellation of associations: “Aryan valley,” “Brokpa culture,” “ancient community.” Such labels are imprecise, sometimes misleading, and yet they point to a real experience of distinctiveness. Approaching Dha, you sense that you are not merely entering another village; you are entering a place that has become used to being looked at.

The houses of Dha cluster together on a slope that feels steeper once you begin to climb it. Lanes twist sharply, staircases appear in unexpected corners, and terraces present themselves suddenly after tight turns. There is a sense of density here – of people, stories, expectations. For visitors, the temptation is to treat Dha as a destination where the “search” for Brokpa culture will finally be satisfied. But the village resists such completion. Conversations often circle back to practical concerns: land fragmentation, educational opportunities, recruitment into the army, climate shifts that affect planting schedules. The symbolic weight carried by Dha in the imagination of outsiders is only one layer of a much more complex reality, in which history is less a grand narrative than a series of decisions about where to plant, whom to marry, and whether to stay.

Why Dha continues to draw travelers, scholars, and wanderers

What, then, keeps Dha at the centre of so many itineraries and research projects? Part of the answer lies in visibility. The village has been written about, photographed and analysed enough times that it has become a convenient reference point for anyone interested in the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor. But there is also something in Dha’s internal rhythm that seems to draw observers. The lanes are narrow enough that you cannot avoid contact; the terraces are close enough that you can hear conversations drifting up from one level to another. Life unfolds within earshot, and that proximity offers both opportunity and risk for the visitor.

For scholars, Dha presents a dense archive of material and immaterial culture; for wanderers, it offers the thrill of encountering a place that feels at once familiar from travel literature and utterly unpredictable in its details. For the villagers, these overlapping gazes can be tiring. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor has taught them to navigate curiosity with a mix of hospitality and boundary-setting. A visitor may be invited in for tea, but not necessarily for photographs. A question about lineage may be answered, but the conversation might quickly shift to the price of vegetables in Leh. Dha continues to draw people because it embodies, in a compressed form, the larger questions that haunt the corridor: how to remain distinct without becoming a spectacle, how to welcome strangers without turning one’s own life into a product.

X. Hanu — Where the Road Narrows and Culture Deepens

The twin settlements that guard the upper edge of the corridor

Beyond Dha, the road winds toward Hanu Yogma and Hanu Gongma, twin settlements that feel like a gateway between worlds. The Indus still flows, but the sense of a continuous corridor begins to fray. The villages are tucked into side valleys and folds, more withdrawn from the main line of traffic, more dependent on a close reading of local topography. For many visitors, reaching Hanu is both a physical and a conceptual turning point. The journey has been long enough to strip away the initial novelty, yet not so long that fatigue overwhelms curiosity. Here, at what feels like the upper edge of the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, culture seems to deepen rather than broaden.

The twin nature of Hanu complicates any desire for neat summary. Hanu Yogma and Hanu Gongma share history, kinship ties and ritual calendars, but each also carries its own texture of daily life, its particular emphases in how houses are built, how fields are arranged, how children move between play and chores. Walking from one to the other, you feel both continuity and distinction. The road narrows, literally, but the range of internal variation widens. For European travelers accustomed to thinking of villages as discrete units, Hanu offers a more fluid model, in which identity is distributed across space and time rather than contained within a single settlement boundary.

The sense of stepping into a cultural preserve

It is tempting to describe Hanu as a “cultural preserve,” a phrase that flatters the visitor’s sense of having discovered something intact. But preserves require curators, and there is nobody here arranging exhibits. What there is, instead, is a network of families making decisions about how much of their world to place within reach of outsiders. Some households welcome guests into homestays; others prefer to maintain distance. Children may switch easily between local language and the Hindi of school textbooks, while elders hold to older terms and stories that do not always yield gracefully to translation.

In the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor, Hanu has acquired a reputation as a place where heritage feels particularly concentrated, and there is some truth to that. Rituals maintain a strong grip on the calendar; seasonal movements of people and animals still follow patterns that disregard the convenience of weekend visits. Yet to imagine Hanu as suspended outside time would be to misunderstand it entirely. Solar panels, school buses and smartphones have arrived here too, albeit unevenly. The sense of stepping into a “cultural preserve” may say more about the visitor’s longing than about the village’s reality. What Hanu offers, instead, is a chance to experience how a community negotiates modernity from a position that is neither naïve embrace nor wholesale rejection, but something more granular, cautious and, in its own way, confident.

XI. Batalik — A Frontier of Landscapes and Histories

The end of the corridor—or the beginning of another

Batalik occupies a charged place in the mental map of the region. For many, the name conjures images of border posts and military histories, references to conflicts that have unfolded along these ridges within living memory. Arriving here after moving through Takmachik, Domkhar, Skurbuchan, Achinathang, Darchik, Garkone, Biamah, Dha and Hanu, you sense immediately that the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor is approaching one of its thresholds. The valley tightens; signs of the state become more visible; the easy assumption of being far from the world’s tensions begins to feel less secure.

And yet, alongside these associations, Batalik is also a place of ordinary life: children walking to school, women tending kitchen gardens, men discussing harvests and road conditions. The Indus flows past with its usual indifference to line-drawing on maps. For travelers, the village presents a set of questions that differ from those posed elsewhere in the corridor. How far is it ethical – or even desirable – to trace one’s curiosity into spaces where other people’s vulnerabilities are more directly at stake? When does a journey along a river become, almost without warning, a journey along a boundary? Batalik does not answer these questions. It simply obliges you to acknowledge that the end of one corridor may be, for those who live here, the beginning of a daily negotiation with forces that travel writers rarely name.

Life in a place shaped by cliffs, currents, and geopolitical quiet

On the ground, Batalik’s rhythms are shaped as much by cliffs and currents as by geopolitics. Terraces climb stubbornly up slopes that give the impression of being only half convinced about their suitability for agriculture. The Indus continues its deep, cool monologue, sometimes far below the road, sometimes almost flush with it. The village walks a line between visibility and discretion, between the necessity of interacting with outside institutions and the desire to maintain a zone of interior life that is not constantly subject to scrutiny.

For European visitors, Batalik can be a sobering reminder that landscapes celebrated for their beauty are also the stage for histories of conflict and unease. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor does not exist in a vacuum; it sits within a web of national narratives, security concerns and shifting alliances. Yet everyday life here still turns, stubbornly, on more immediate axes: the depth of snow in winter, the reliability of water in summer, the viability of keeping young people interested in farming when cities sparkle with alternative futures. To spend time in Batalik is to realise that “quiet” in such a place is never merely the absence of noise; it is an achievement, provisional and fragile, held together by routines that look mundane until you imagine their absence.

XII. Closing: What the Lower Indus Offers the Traveler

A corridor that rewards patience rather than ambition

Taken together, the villages of Takmachik, Domkhar, Skurbuchan, Achinathang, Darchik, Garkone, Biamah, Dha, Hanu and Batalik form more than an itinerary; they form a proposition about how travel might be conducted in a century already crowded with destinations. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor does not lend itself easily to bucket lists or quick triumphs. Its peaks are mostly unnamed, its “sights” distributed across households rather than consolidated in monuments. To move through it demands patience: with the road, with the altitude, with your own expectations of what constitutes a successful day.

This patience is not a virtue you bring with you so much as one that the corridor quietly trains into you. Days take on the pace of irrigation cycles rather than museum opening hours. Conversations unfold in courtyards and kitchens, full of pauses and detours that refuse to be streamlined for narrative efficiency. In such a context, ambition—at least the kind that counts summits or stamps—feels faintly out of place. What matters instead is the ability to notice: how Skurbuchan Monastery catches the first light on a winter morning; how the apricot trees in Achinathang mark the edge between habitability and hazard; how the irrigation channels of Garkone double as both infrastructure and conversation space.

In a world where travel often means collecting places, the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor suggests another possibility: allowing one small stretch of river to collect you, rearranging your sense of time, scale and what counts as enough.

For travelers willing to accept this invitation, the corridor becomes less a route to be completed than a teacher whose lessons are never quite finished. It rewards those who stay longer in fewer villages, who return to the same path at different hours, who understand that not every encounter needs to be translated immediately into a story told elsewhere. Patience here is not passive; it is an active choice to align oneself, however briefly, with the slow urgencies of a valley where snowmelt, seed and sunlight still determine what is possible.

The Brokpa villages as a slow unfolding of identity, land, and meaning

In the end, what the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor offers is not a single revelation but a slow unfolding. Identity here is layered: Brokpa, Ladakhi, Himalayan, national – all coexisting in ways that defy simple classification. Land is not a backdrop but a demanding partner, insisting on being read closely, tended patiently, respected in its moods. Meaning arises in the interstices: between Skurbuchan’s monastery and its fields, between Darchik’s festival regalia and its ordinary workdays, between Hanu’s sense of continuity and Batalik’s exposure to the wider world.

For European travelers used to thinking of “remote communities” as either endangered or romanticised, the corridor offers a third possibility: communities that are neither frozen in time nor rushing headlong toward homogenisation. They are improvising, adapting, debating. Homestays open and close; young people leave and sometimes return; festivals absorb new elements while trying to retain their core. To witness this unfolding is not to become an expert on Brokpa culture or Indus valley agriculture; it is to be reminded that cultures, like rivers, are always in motion, even when they appear briefly still.

FAQ: Traveling the Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor

Q1. How many days should a traveler plan for the corridor?

A stay of at least five to seven days allows you to move beyond snapshots, spending real time in two or three villages and adjusting to altitude and rhythm rather than simply passing through.

Q2. Which villages are most suitable for first-time visitors?

Takmachik, Skurbuchan, Darchik, Garkone and Dha offer a good balance of homestay options, accessibility and cultural depth, while still feeling grounded in everyday village life rather than pure tourism.

Q3. How can visitors travel respectfully in Brokpa communities?

Ask before photographing people, dress modestly, accept that some questions will not be answered, and remember that your curiosity is never more important than a family’s need for privacy, rest or unobserved ritual.

Q4. When is the best season to visit?

Late spring to early autumn offers accessible roads, active fields and orchards in leaf or fruit, but coming slightly outside peak months can reduce pressure on homestays and allow more unhurried conversations.

Q5. Is it necessary to book everything in advance?

It is wise to arrange the first night or two, especially in smaller villages, yet leaving some days open lets you respond to local invitations, weather shifts and the simple desire to stay longer in a place that speaks to you.

If there is a conclusion to be drawn from all of this, it may be a modest one. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor will not transform the global conversation about travel or development. It will not solve the dilemmas facing Himalayan communities under climate stress, nor will it rescue European travelers from the contradictions of long-distance flights to fragile environments. What it can do, however, is sharpen our awareness of those contradictions and offer, on a human scale, examples of how people live with them every day. In Takmachik’s experiments with sustainable tourism, in Skurbuchan Monastery’s quiet watch over its fields, in Darchik and Garkone’s negotiations with visibility, in Biamah’s unhurried evenings, in Dha and Hanu’s layered identities, in Batalik’s daily balance between border and home – there are clues to ways of inhabiting both place and time more attentively.

For the traveler willing to listen, the corridor whispers a closing note that feels less like a farewell than an assignment. Go back, it seems to say, and pay closer attention to your own river, your own village, your own quiet corridor through the world. Notice where water comes from, how food arrives, which stories you tell about your neighbours and which you neglect. If a narrow stretch of the Indus valley can hold so much complexity, there is little excuse for pretending that any place is simple. The Lower Indus Brokpa Corridor does not ask to be admired. It asks, gently but persistently, to be understood—and, in being understood, to change the way you move, not only here, but everywhere else you go.

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective dedicated to the silence, culture, and resilience of Himalayan life.

His essays follow slow roads, small villages, and the understated beauty of high-altitude landscapes.