The famous Howrah Bridge over the Hooghly River in Kolkata. Photo: Dipan Maity/iStockphoto

In a place where trees ravage homes

The winds of change blow in Kolkata

In Kolkata, time spins and it seems citizens can evade the future. Here, poetry still holds more value than money, and fig trees grow in old bedrooms. This city gradually bends to nature and may someday be devoured by it.

“It’s the perfect place to spend retirement,” says Iftekhar, her black hair tied up in a high ponytail, eyes gleaming with excitement. Pulling at the damp linen shirt clinging to her body, she surveys the surroundings. We rush through the missing double doors from the street, past the first small courtyard. Now, we stand beneath the columns surrounding the spacious second courtyard. Warm rain falls suddenly, like in the monsoon season. Rainwater streams directly into the central marble fountain, once the pride of this house and the centerpiece of the courtyard. Now, it’s a trash bin for all sorts of junk like pots and wooden planks. The city and its people refuse to let go of the past. They hoard, they cling. Welcome to Kolkata Time Shelter.

“You can arrange some rooms in each section of the house, each with a balcony. Imagine. Living like in your youth. Craftsmen, hawkers, newspaper vendors—they all come. And children from the red-light district and slums along the riverbanks come too. Retirement will be beautiful,” Iftekhar imagines, leading me through a retirement home that recreates the old world. Walking the old paths is still possible in Kolkata, unlike in other cities. Here, daily life changes slowly, sometimes unnoticed as time passes. In Hinduism, time is not a straight line but a circle. It doesn’t vanish; it returns, it just exists.

Iftekhar’s dream remains a fantasy. She shows me her business plan while wiping the smartphone screen on her jeans. Everything is planned, segmented, and prepared for realization. But investors are needed, as well as the consent of the last inhabitant of this building. She lives alone, almost cut off from the world. She doesn’t venture outside. Everything is brought to her by servants, a typical luxury in Kolkata. Without exposing oneself to dust, smog, noise, or crowds, everything can be delivered. Endure the heavy wooden ceiling fans rotating overhead in the arcades of well-designed houses, or simply be immobile. Not chasing “tomorrow” or “better” or “more,” just “being.” The future and progress leave no impression on Kolkata or its veteran residents. The inheritor of this mansion, with white hair and a stylish worn cotton saree, just peeks out the window and closes the shutters. She has no expectations left in this world. And the world expects from her, in this case, an ambitious forty-year-old with plans to regenerate the building and make the elderly happy, doesn’t need to realize it immediately. It can wait.

All we can do is watch as homes decay slowly but surely. Kolkata’s beautiful houses deteriorate with the aging residents. Like organisms following the same rules as their inhabitants—fatigue, illness, longing for tenderness—they somehow endure as long as everyday life persists. Houses that have stood for decades, centuries, one afternoon collapse due to heavy rains, decay, loneliness, or simply fall to the ground.

The old lady clad in lace

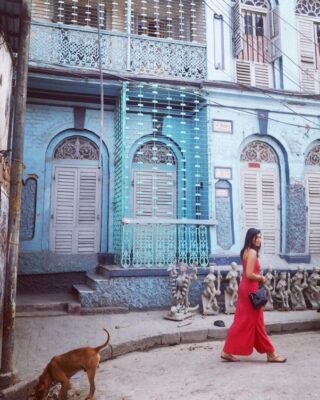

What Iftekhar and I are seeing now is a house still pulsating, still breathing, yet its former splendor hidden under decay. The courtyard surrounding the fountain is paved with stone in plant motifs. Surrounding it, the single-story house sprawls symmetrically in all directions. Wooden blinds, reminiscent of Sicilian architecture, adorn the windows on the ground floor. The enclosed shared balcony on the second floor has sculpted railings. This balcony once served as the main artery of the house, connecting all rooms like a corridor. The top floor was a private space where family life flourished. Downstairs was reserved for servants, kitchen, guests, and family rituals or religious ceremonies. From the balcony, milkmen and vegetable vendors could be observed. Anything cumbersome to carry up and down the stone steps, like keys, fresh flowers, or ironed laundry, went in bags with strings. These bags still number in the millions throughout the city.

Today, these balconies are cluttered with boxes, pots, and laundry. The assortment of clothes and miscellaneous items suggests that destitute people unrelated by blood inhabit this dwelling. While there is clutter, there is still space in the rooms, once a luxurious mansion where multiple generations lived. Reflective of the architectural style favored by wealthy Bengali aristocrats who amassed fortunes during British colonial rule since the 17th century. They traded in jute, tea, and opium, the most valuable currency brought from Afghanistan and loaded onto ships bound for China from here.

Colonial buildings during British rule. Photo: Joerg Boethling/Alamy Stock Photo

It was the local elite aristocrats who built the region called Northern Kolkata, the heart of Kolkata today. Pace setters of urban ambition and artificial joints have been built in recent decades. But there’s no need to rush here. Kolkata arrived on this stage late. Compared to medieval Delhi or ancient Varanasi, Kolkata, the metropolis of the industrial age, seems like a dowdy old lady in lace, yet it’s the youngest city among India’s largest cities. The hostile climate and capricious history have left their marks on this city. Until the 17th century, there were only fishing villages and marshes and swamps prone to malaria along the tributary of the Ganges, the Hooghly River, which flows into the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. British envoy Job Charnock (1630–1693) saw this place as an opportunity for the empire. The Bay of Bengal provided a safe haven for ships due to its low banks, making it an ideal starting point for journeys from India to the “Far East.” Of the three villages Charnock purchased (one of which was called Kalikata, later influencing the name the metropolis would acquire), it was becoming clear that the future capital of the royal colonial estate would be a tropical London. Some bribes and battles were needed before urban construction was legalized. Since no buildings were yet erected, Charnock held his initial meetings with contractors in the shade of a 300-year-old banyan tree.

The Ivory City

Originally, only a handful of British businessmen closely collaborated with the majority Bengali population. The initial settlers showed interest in the local culture, language, and faith. However, as the prospects of wealth grew, more people flocked to Kolkata tempted by the vision of profit, and their desire for isolation and dominance intensified. In the 18th century, the so-called “Ivory City” (referring to the skin color of colonial-era residents) emerged. The modern heart of Kolkata was surrounded by vast neoclassical edifices, meant to delight, intimidate, and obscure who exactly was ruling over India. Grand structures like the Post Office, High Court, and Victoria Memorial were enclosed by sprawling boulevards separated by extensive parks and squares. At the site once known as Dalhousie Square stood the imposing “Death Letter Office,” where missives addressed to the deceased were kept. Kolkata’s humid climate induced numerous illnesses, mercilessly claiming the lives of royal merchants and accountants. Tombstones in the Christian cemetery on Park Street narrate the difficulty of surviving past the age of thirty. At New Year receptions held in the Town Hall, attendees earnestly blessed each passing year. However, letters missent remained untouched until the building was repurposed into a telegraph office, and unread correspondences regarding love, longing, and financial reckonings vanished. Kolkata seems incapable of engaging with its own history or respecting its heritage. It embraces decay and dampness, almost revering it. This inertia can be seen as a malaise corroding the city’s soul or perhaps as a display of humility. A city can triumph, promise a better tomorrow, but who ever said it must? A city can yield, show maturity, and come to terms with its own passage.

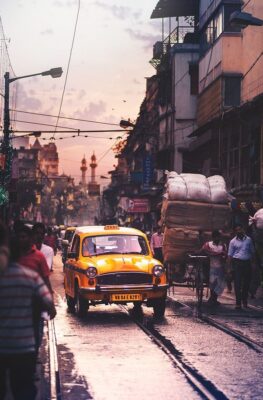

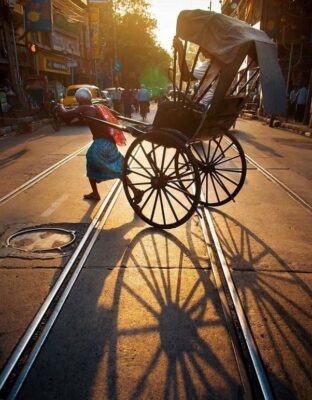

In the ‘White Town’ of the British era, Kolkata boasted fortifications for defense (though the marshy surroundings made actual attacks unlikely), a racecourse, and the vast Maidan (a parade ground for brigades), ideal for showcasing military might. Until Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, departed from Mumbai by ship in 1947, Kolkata served as an ideal venue for massive protests and strikes, catching the British off guard. For two centuries, Bengalis had permeated the most impressive buildings of Kolkata as servants. People drank coffee in Italian cafes, rested in luxury hotels, danced, and watched carriages roll by the streets. Such splendor is unimaginable today. Thousands of stalls line the city’s arteries, where the poor eke out modest lives. Meanwhile, dilapidated buses, rickshaws, bicycles, and tuk-tuks, alongside barefoot rickshaw pullers, traverse the roads with a rhythmic shuffle. Recently, Uber drivers in battered white Toyota cars and nouveau riche in SUVs have joined the fray, mingling in the belly of the metropolis where 17 million people coexist, embodying the worn beauty of independent India’s provinces.

During the construction of the Ivory City, indigenous peoples were pushed northward. From there arose what was known as the Old Kolkata, referred to as the “Black Town,” indicative of its residents’ skin color. Kolkata’s street network became denser, diversity became the norm. Followers of many religions lived on adjacent streets or next to each other. The last remaining synagogue is cared for by Muslims due to the scarcity of elderly Jews. Fires burn in Zoroastrian temples. Only 234 temples remain scattered throughout the city. But why did these sparse devotions not coalesce into a vibrant current? That was the case with the resurgence of Indian Buddhism in Kolkata. Temples for the Chinese, Jains, and Sikhs thrive. Amidst Hindu temples and Islamic mosques, though minorities, all sects can dwell securely. Kolkata forced history to learn acceptance and hospitality. By engaging in trade with the British, merchants, artisans, and servants of all religions flocked in droves. Colonial policies corralled them into stratified spaces, subjugated them to colonial rule, and unified them under the same fate.

Black Town

Before the arrival of Europeans, Bengal already had elites, nobles, and powerful Nawabs (governors), but colonial rule birthed a new class. The Babus were the nouveau riche of 19th-century Kolkata. They rode in horse-drawn carriages pulled by zebras, washed their residences with rosewater every morning, and threw lavish, expensive weddings for their pet dogs. Yet, amidst being the granary of India, there existed individuals associated with the sophisticated culture of the Bengal region, intellectuals, and artists. Babus donated their wealth to the development of arts and education. Architects imported from the Middle East and Europe designed magnificent mansions with courtyards, guesthouses for artists, stages, and theaters. The audience consisted of neighbors, and the Babus proudly showcased their patronage of top-tier dancers, musicians, and poets. The zeal for arts and culture emanated widely from these outdoor salons (performances held in courtyards), enabling artisans, janitors, and shopkeepers in Kolkata to recite poetry and sing even today. Wealthy nobles donated land to universities and colleges, funded hospitals and markets, and supported ghats (stone steps for washing, communication hubs for boats and ferries, sites for cleansing rituals and temple prayers) along the riverbank.

The Mansion adorned with antique collections, a rickshaw puller stands at the gates of Marble Palace. Photo: volkerpreusser/Alamy Stock Photo

The house consuming trees. Photo: Balaji Srinivasan/iStockphoto

The affluent lineages like the Mullicks and the Tagores have left their distinct imprints on the city’s vision, passion, and ambition. A fusion of Western influences and local elites, Kolkata became a metropolis bringing modernity to South Asia. It was the first town in this region to have a telephone network and elevators. Early electrification covered the entire district, teaching residents to ride the first tramcars. Kolkata boasted the first printing press in the subcontinent (even today, a manually operated printing press from 200 years ago is still used in the university area), the first secular university, and the first computer. There was a time when Kolkata evoked thoughts of groundbreaking innovations, novelties, and inventions. It’s now hard to believe while sipping morning tea at the ghats, a few minutes’ walk from where once stood Job Charnock’s banyan tree, now thriving with stations.

Amidst the bustle of the morning, on the steps, a dozen men engage in bathing and prayers. Boats laden with small parcels and fish arrive. In this place where kitchens blend with temples, one can savor the city’s best tea. Rich, sweet, with delicate spices that scorch lips, revive, and fortify. A woman in her fifties pours boiling drinks while chatting on her mobile phone. A boy, presumably her son, briskly decorates statues and paintings of the goddess Kali. He retrieves garlands of jasmine and hibiscus from a bag, hangs them, and begins burning incense. The day begins with praise to the gods, for without their grace, no trade would flourish. So, incense is lit, hands are clasped, prayers whispered. Meanwhile, a large pot simmers on the stove. Soon, truck drivers parked nearby arrive post-bath, clad in sleeveless tank tops, wrinkled pants, rubber flip-flops, to relish potato curry and flatbreads. The sound of slurping, spitting, and shuffling feet can already be heard.

Behind the line of parked cars, narrow lanes intertwine, old houses, grand mansions dating back 300 years, slightly newer smaller buildings form the living archives of the past. Ancient architectural marvels, modified, with new terraces, balconies, and roofs, modernized just slightly, equipped with various functionalities, crowd together. It’s hard to distinguish where the workshop ends and the restaurant begins, whether this room is a kitchen or a large family’s home. Layers of life overlap, coexisting without pushing one another away. While many cities worldwide attempt self-reformation, old Kolkata remains unchanged. Absorbing epochs of ideological shifts, inventions, and beliefs, it has existed simultaneously for centuries. Here lies the wisdom of accumulating knowledge, material, and ideological diversity organically and dispersedly, rather than propelling towards modernization. Most homes, buildings, factories, and warehouses in the northern part of the city belong to no one. Despite being densely populated and heavily utilized, they remain somewhat isolated as no one takes responsibility for their condition or future. It’s because the winds of history brought great misfortune and dreams to Kolkata, slowing each other down and nurturing together.

Time over Money

Under British rule, Kolkata thrived until 1912 when the capital moved to Delhi. With it, not just money but also the fervor for the future began to wane. Unfair land ownership imposed by the British persisted in the agricultural regions of Bengal. Consequently, poor farmers piled up debts. When World War II broke out, they were obligated to produce more to support the British army, leading to further inflation in food prices. Ignoring the colonial rule-induced famines, nearly four million people perished. At that time, the first wave of people arrived in Kolkata, desperate to survive.

In 1947, as Britain departed from the subcontinent, dividing it into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan, even more people poured in. This partition fueled religious animosity, leading to bloody massacres. Kolkata saw millions of refugees flooding in. The city suffocated under the weight of refugees, its streets teeming with homeless forced into begging and hunger. Kolkata became the epicenter of global poverty. Today, lacking infrastructure, space, and jobs, slums emerged. Modestly put, it’s an informal district, expected to witness a surge in the proportion of the world’s urban population over the next few decades.

In the 1970s, a third wave of immigrants, famine refugees from Bangladesh, transformed the villages in southern Kolkata into suburbs. Eventually, these villages were encircled by ring roads and absorbed into the city. Newly planned areas like Bidhannagar aimed to alleviate overcrowding. But envisioning a better life in skyscrapers touching the sky necessitates negotiation with nature. Kolkata is dangerously approaching the Gangetic delta region, necessitating drainage of wetlands, the most crucial natural barrier against floods, cyclones, and rising water levels. As Kolkata moves towards the future, it’s shrinking its own territory. This city is a victim of late capitalism, in the stage of “growing to die.”

In the oldest districts of Kolkata, the flow of money is entirely different from middle-class residential areas. Here, money still doesn’t mean as much as poetry, simple prayers, moments spent together under trees, or chatting over tea. Time is not just money.

Not everything has a price tag. Water is free. In drought-prone India where conflicts over water are commonplace, free access to this common resource seems to be a genuine social phenomenon. Abandoned mansions once owned by nobles are now inhabited by refugees, agricultural laborers, economic migrants, one after another. Do they have the right to live there? It’s simple, a law of urgent necessity faced with a state that cannot provide prosperity to much of its population. And it’s a law of history. Kolkata has been ruled by elected Marxists since the 1970s. Since then, anyone residing in a dwelling for five years becomes its legitimate occupant. Few owners are keen to confront the bureaucratic machinery enlarged by the Marxists.

During the era of the leftist local government, there was a significant stagnation. While industries and skyscrapers flourished in other parts of Asia, Kolkata repelled investors with strikes and labor unionization. For 35 years, the ideology of promoting the working class was practiced. The free-market reforms that swept India in the early 1990s arrived in Kolkata 20 years later but never fully took root. There are no international corporations or brands, no pursuit of profit, no conducive working environment to build a career. Dreamers departed, leaving behind only the romantics.

Stormy Weather

Now, Anjali, sitting with me, sharing tamarind-flavored sherbet, is one of them. We’re seated at the legendary drink shop “Paramount,” just off College Street, the street of bookstores. Waiters wander around, serving glasses filled with crushed ice and sweet fruit syrup. Throughout Kolkata’s history, significant figures, just like us now, sat here, making noise with their throats. Writers, poets, revolutionaries, scholars, filmmakers… the intellectual class of this city, they created with the city’s unique imagination. However, Anjali, at 24, feels she might soon succumb. Unlike her friends who graduated from journalism school with her, she didn’t move to places like Mumbai or Delhi, where life moves fast, where one might climb to the top of the career ladder.

Anjali, deeply enamored with Kolkata, had no intention of leaving, hence she became my guide. Together, we ventured out, unraveling the new facets of the city we’ve been gradually discovering over the past two decades. Anjali, a young woman herself, also enlightens me about Kolkata ushering in a new chapter. “Once filled with academia and poetry, the city is reverting to its village roots. For the first time in centuries, the youth no longer dream of education or improving their quality of life. They don’t even dream of happiness. They just want to make money fast,” Anjali remarks. Adding to her sentiment, Koel, a travel enthusiast and an Instagrammer, says, “Ambitious folks move to more developed cities. Kolkata is where people from rural areas congregate. While my friends board planes, trains from villages arrive in Kolkata every day.”

To verify this, Anjali and Koel took me to Sealdah Railway Station, a symbol of commuting hell, chaos, and turmoil. The platforms were seas of people, endless crowds, constant motion. “A million people come here every day,” Anjali remarks. “And as you can see, it’s not for desk jobs.”

And indeed, it’s evident. Cheap synthetic clothes, sun-darkened skin exposed for hours, swollen veins, tied-up hair, calloused feet and hands from manual labor… These are the people Kolkata’s new populist authorities have been addressing for nearly a decade. Local politicians are “beautifying” the city by refurbishing monuments to entertain newcomers arriving from rural areas. They also simplify the process of migration and obtaining basic jobs. The urban intellectual elite feels compelled to ally politically with rural parties serving the poor, as they perceive it as the survival strategy against a government of hate rather than for the people. Professors and filmmakers opt for a smaller evil, choosing a government of the people, not of hate. They too are trying to survive.

People like Iftekhar and Anjali, who strive to preserve Kolkata’s heritage of architecture, customs, and legends, are leaving it to their judgment. They’ve chosen the role of memory keepers. Both acknowledge that nurturing memory is a luxury in this world where the overwhelming majority wrestles with the daily grind. Today, this city belongs to them.

What lies ahead for Kolkata? Perhaps it’ll become a collective of villages overflowing with regional identities, close relationships, and small-scale businesses. Or it might transform into one vast village, enjoying the luxury of swift commutes and concentrated commerce. Alternatively, it could lose its center, forfeit the path of progress, and collapse. Maybe it’ll lose its vigor or, conversely, turn towards tradition and faith, surviving amidst fragmented diversity and conservative morality.

These questions encapsulate the essence of present-day Kolkata. This city shares the very unglamorous future plaguing many cities worldwide. It’s the reality of mass migration to urban areas in Asia, Africa, and South America, devoid of any ideals. Millions arrive in urban areas without preparing for such a scenario, hence the new residents can’t be provided with what they desire. Immigrants often haphazardly utilize urban areas, paving their own way without consulting anyone, without looking back, creating makeshift neighborhoods, and building new layers of life. While this trend is devastating on a global scale, no one can stop it. Cities emit the most greenhouse gases and are a primary cause of climate change. Taking shelter in major cities is akin to running towards a tornado.

Perhaps the ultimate answer to these questions will come from nature itself. If the inhabitants of Kolkata are not forced into exile by a major disaster, nature will slowly reclaim the areas it has peeled away from. People settled in this land, paying the price of drying up the land. Now, the greatest threat to everything they have created is water. The sea is becoming increasingly bold, encroaching more and more into the lands around the Bay of Bengal, decimating crops. Monsoons and floods damage buildings, washing away roads and elevated highways. With each rainy season, the number of collapsed buildings increases. Two years ago, a powerful cyclone ravaged the alleys of Kolkata, blowing off roofs and tossing people around like puppets. Yet, the fig tree quietly thrives. It grows between the bricks of old houses, slowly enveloping the entire structure. Its branches reach out to balconies, its roots penetrate windows into the rooms. Thus, nature absorbs culture. Perhaps it’s an era of returning to the natural order. Tales of kingdoms devoured by the jungle won’t be new.

Iftekhar has succeeded, for now, in preserving just one old building. Inside, he has set up a small hotel. He is considering preserving other ruins for purposes like cultural centers, libraries, and recreation centers. Recently, this eccentric affection has become not his alone. Someone in the neighborhood is renovating a 200-year-old tenement. Two sparrows joined together and flew off, slicing through the wind.