Where Quiet Roads Shape the Heart of Nubra Valley

By Declan P. O’Connor

I. Opening Reflections: Entering a Valley of Two Rivers

The First Descent from Khardung La

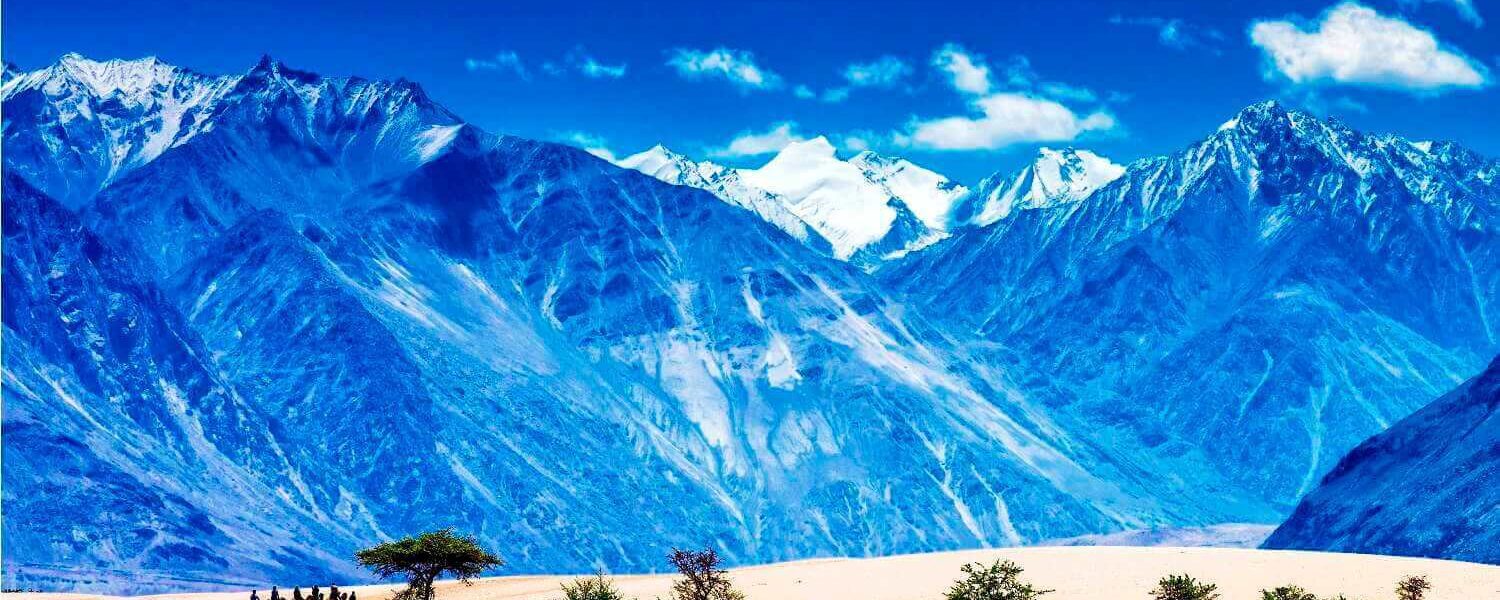

On the far side of the high pass, the air changes before the scenery does. The road that drops from Khardung La into Nubra Valley does not simply move you from one altitude to another; it feels as if it is lowering you into a different register of sound, light, and time. The city behind you is still busy, full of horns, itineraries, and signal bars that flicker in and out. Ahead, the valley opens slowly, not with a single cinematic vista but with a series of small revelations: a string of whitewashed chortens, a ribbon of water glinting in the distance, the first patchwork of fields pressed against bare rock.

Nubra Valley is not a single landscape but a meeting point of many: glaciers feeding rivers, rivers feeding villages, villages keeping cultures alive that once travelled all the way to Central Asia. As you descend, you begin to understand why this place has always mattered more than its map size suggests. It has hosted caravans and pilgrims, soldiers and farmers, monks and schoolchildren. The further you drive, the more the road feels less like infrastructure and more like a slow, grey thread stitching together lives along the Shyok and Nubra rivers.

How Landscapes Become Cultures in Motion

At first glance, the valley’s geography seems to dominate the story: the broad, braided rivers, the sheer cliffs, the improbable apricot trees that somehow thrive in the cold desert. Yet the more time you spend moving from one settlement to another, the more you realise that Nubra Valley is less about scenery and more about circulation. Ideas move here. Languages shift slightly from village to village. Religious traditions share walls, festivals, and sometimes even family trees. It is a place where the old Silk Route never fully disappeared; it simply slowed down and became local.

The road from Khardong to Turtuk is therefore not just a drive through a postcard. It is a long, looping conversation between mountain and river, between monastic courtyards and barley fields, between Ladakhi, Balti, and the quiet codes of hospitality that still matter more than Wi-Fi passwords. As you follow the asphalt northwards, you begin to understand each village as a different answer to the same question: how do people learn to live, and keep living, in such a demanding yet generous landscape?

II. Khardong: A Village that Watches the Pass

Life Above the Valley Floor

Before most visitors even realise it, they have already passed the first of Nubra’s high-set guardians. Khardong sits above the main valley floor, closer in spirit to the pass than to the river, as if it were still listening for the sound of caravan bells on the horizon. Houses cluster along the slopes in a way that looks precarious from a distance, but once you are walking the lanes, it feels surprisingly logical. Each courtyard, each rooftop, each small patch of field seems angled to catch a fragment of sun or a view onto the mountains.

Life here is practical, unsentimental, and adapted to altitude. People think in terms of fuel, fodder, snowmelt, and wall thickness before they think of itineraries and hashtags. Yet this does not mean that the village is closed to the world. On the contrary, many families have stories of relatives working in Leh, in the army, or even abroad. Children grow up with one foot in an ancestral rhythm of planting and harvesting, and another in an era of school exams and video calls that cut out whenever the signal tires of climbing the mountain. From a cultural perspective, Khardong offers a first glimpse of how Nubra Valley negotiates between the old and the new without losing its footing.

The Old Routes and the Quiet Rhythm of High-Altitude Living

If you pause for a day rather than a few minutes, the quieter logic of Khardong becomes clearer. Paths that appear aimless from the road turn out to be careful lines connecting water to house, house to field, field to prayer flag. Stories about the old trade routes still surface in conversation, not as nostalgic set pieces but as practical memories: which slope was safest in a heavy snow year, where travellers once sheltered, when grain used to arrive from far beyond the current border. The village’s relationship with the pass is not romantic; it is about survival, supply, and sometimes sudden isolation.

Yet in the evenings, when the wind drops and the last vehicle’s echo fades, there is a calm that feels almost deliberate. Families gather on flat roofs, children chase each other along stone walls, and the village seems to lean back and watch the sky for a while. In that pause, you can sense why people stay, and why the road that continues toward Nubra Valley is not only an escape route to somewhere more famous, but also a lifeline back to this hillside above the river.

III. Sumur: The Stillness Around Samstanling

Monastic Silences and Village Life

By the time you reach Sumur, the valley has widened and your shoulders have dropped a little. The tight bends of the descent give way to longer, more generous stretches of road, and the air seems to carry more moisture, more birdsong, more of the low, warm sounds of village life. Sumur is known to many visitors because of Samstanling Monastery, but to think of it as simply a monastic stop is to miss its deeper character. Here, the religious and the everyday sit side by side in a way that is understated but unmistakable.

The monastery rises above the fields, with prayer flags stretching like delicate bridges between building and cliff. Inside, the air is thick with butter lamp smoke and the slow murmur of chants. Outside, just a short walk away, women work in the fields, men carry tools along irrigation channels, and schoolchildren swing their backpacks with the familiar impatience of the end of the day. The silences of Samstanling are not removed from village life; they are part of its rhythm, shaping how time is felt, when decisions are made, and how misfortune or good harvests are interpreted.

Why Sumur Became a Cultural Anchor of Nubra

Sumur’s role as a cultural anchor in Nubra Valley is not something that arrived with tourism. Long before guesthouses appeared, the village functioned as a kind of spiritual and social reference point for surrounding settlements. Stories, advice, and rituals travelled here along with goods and greetings. In that sense, Sumur has served as an informal archive of memories: the place where elders remember the exact year of a difficult winter, where monks can recount how certain practices came to the valley, and where families return for major life events even after they move closer to towns and jobs elsewhere.

For visitors, this anchoring role is not always obvious at first glance. It reveals itself in small moments: the way a farmer pauses to speak with a monk on the path, the ease with which neighbours step into each other’s courtyards, the respect given to seasonal and religious calendars. When you walk slowly through Sumur, you begin to see that it is less a picturesque backdrop and more a living institution in its own right, one that helps hold together both the spiritual and the practical threads of the valley.

IV. Kyagar: A Settlement Between Memory and Movement

Where Trade Routes Once Converged

Driving from Sumur to Kyagar, you can feel the valley narrowing and widening, as if it is breathing. Kyagar itself appears modest: clusters of homes, stretches of farmland, the everyday details of rural Ladakh. Yet beneath this apparent simplicity lies a history shaped by movement. Trade routes once converged in this part of Nubra Valley, linking it to regions that now lie across guarded borders and on distant maps. While the caravans have gone, their echo remains in the way people here talk about distance, opportunity, and risk.

Older residents speak of journeys that would now be impossible, of relatives who settled in places that are no longer mere stops on a shared route, but separate worlds on the far side of lines drawn by politics. The geography that once allowed movement now sometimes restricts it, yet the memory of that openness continues to influence how people in Kyagar view visitors, trade, and the future. The village stands as a reminder that even quiet settlements have long, outward-looking histories, and that the road you travel today is just one layer over older paths.

The Changing Tapestry of Daily Life

Daily life in Kyagar, like elsewhere in Nubra Valley, is changing in ways that are subtle rather than dramatic. Fields still need tending, livestock still requires care, and festivals still bring together families scattered by work and study. At the same time, smartphones glow in kitchens, weather forecasts are checked before planting, and conversations about children’s futures increasingly include words like “degree,” “training,” and “abroad.” The tapestry of life here is being rewoven, but not from scratch; new threads are being added without entirely removing the old ones.

Visitors who stay more than a single night see how these layers overlap. A teenager might help his parents with irrigation during the day, log on to watch a football match in the evening, and then, without any contradiction, join his family at the prayer room shrine before bed. This coexistence is perhaps the most striking aspect of Kyagar: the ability to absorb change without losing the core patterns of cooperation, seasonal work, and shared responsibility that have defined the village for generations.

V. Panamik: Steam Rising from the Edges of the Valley

Hot Springs and the Science of Cold Deserts

Panamik is often introduced to outsiders through a single detail: its hot springs. Photographs show pools surrounded by bare rock, wisps of steam drifting into cold air, and the familiar juxtaposition of thermal water in a high-altitude desert. But to stop at that first impression is to miss the fuller story of how Panamik fits into the broader fabric of Nubra Valley. The springs are not just a curiosity; they are part of the local understanding of health, healing, and the sometimes surprising generosity of this landscape.

In a valley where winters are long and work is physically demanding, the idea that warm water can rise from the earth carries both practical and symbolic weight. People come to soak sore joints, to talk, to rest. For visitors, the experience can feel like a small miracle, but for residents it is woven into a more complex relationship with the environment—one that includes snowmelt calculations, concerns about changing weather patterns, and a growing interest in how climate science explains what elders observe in the fields and on the slopes each year.

Fragmented Histories of the Silk Route

Panamik’s position along the old Silk Route once gave it a significance that stretched far beyond its current boundaries. Caravans used to pass through, and stories of trade, diplomacy, and hardship accumulated here over centuries. Today, those routes are fragmented by borders, and the idea of moving freely across them belongs more to memory than to daily life. Yet when you listen carefully to older villagers, you realise that the echoes of those journeys still shape how the community sees itself.

There is a certain outwardness in the way people discuss the world beyond Nubra Valley. It is not the abstract global awareness of news feeds, but the concrete knowledge of how routes once connected this place to larger economic and cultural systems. In conversations about tourism, infrastructure, and education, you can sense that Panamik does not think of itself as a remote outpost, but as a village that has quietly watched the world pass by in many forms. The hot springs, the stories of traders, and the present-day visitors all form part of a longer, evolving narrative about connection and distance.

VI. Diskit: The Valley’s Beating Cultural Center

The Monastery That Has Seen Centuries

Approaching Diskit, the eye is drawn first to the monastery clinging to the hillside and the large statue overlooking the valley. It is easy to treat this as a checklist sight—a place to photograph, to tick off in a guidebook, to view from a safe distance. But the monastery is more than a backdrop. It is a living institution whose corridors have felt the passing of centuries, whose walls carry the marks of both devotion and time, and whose monks are very much part of the contemporary life of Nubra Valley.

Inside, the cool dimness contrasts with the brightness outside. Butter lamps, painted deities, and the soft brush of robes against stone make it clear that this is not a museum. It is a working religious space where festivals are prepared, debates held, and children learn not only philosophy but also how to navigate a world that now includes visitors from many countries. From the terraces, the view over Nubra Valley is expansive, but what makes Diskit truly central is not just its vantage point; it is the role it plays in weaving together spiritual, educational, and communal life for many of the villages strung along the rivers.

Modern Nubra and the Weight of Continuity

Diskit is also the closest thing Nubra Valley has to a small town, with its shops, schools, and administrative buildings. Here, the conversations about road conditions, exam schedules, agricultural subsidies, and mobile coverage become more concentrated. The weight of continuity lies in how these practical matters are negotiated without losing sight of older obligations: to monasteries, to fields, to family shrines, and to the rhythms of festivals that structure the year.

In a café or a roadside stall, you might overhear young people discussing work opportunities in Leh or further afield, even as they plan to return home for harvest or for a major religious ceremony. Diskit is where the future of Nubra Valley is being quietly negotiated: between the desire for education and income, and the wish to remain in a place where the mountains, rivers, and monasteries are more than scenery—they are anchors of meaning. The result is not a dramatic clash but a careful balancing act, visible in the mix of traditional dress and down jackets, of prayer flags and phone chargers sharing the same nail on the wall.

VII. Hunder: Dunes, Camels, and Unexpected Landscapes

Where the Desert Meets the Glaciers

Hunder is the village that often surprises even seasoned travellers. The sight of sand dunes and Bactrian camels against a backdrop of glaciers unsettles the usual mental categories of landscape. It is as if several climates had agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to share the same stretch of valley. Tourists come for this spectacle, and for good reason: it is not every day that you can watch a camel caravan move through an alpine desert as the light slides down from snow peaks.

Yet the true interest of Hunder lies not only in what it offers to the camera but also in what it reveals about adaptation. The people of Hunder have learnt to work with a landscape that is constantly shifting—literally, in the case of the dunes, and figuratively, in the sense of changing visitor numbers and expectations. Fields extend like green statements of intent at the edge of the sand, and old irrigation channels continue to do their quiet work. The village shows that living in a place of contrasts is less about spectacle and more about patient negotiation with water, wind, and opportunity.

Community Life Beyond the Touristic Glimpse

For many visitors, Hunder is an afternoon or overnight stop, a place to ride camels, cross a bridge, and perhaps watch the sky shift colours over the dunes. But community life extends well beyond this brief window. Early mornings belong to farmers and students; late evenings to families gathered in courtyards, catching up on the events of the day. The presence of tourism can be felt in new homestays, cafés, and signboards, but it does not erase older patterns of cooperation and mutual support.

One of the quiet questions facing Hunder—as in much of Nubra Valley—is how to welcome outsiders without allowing the logic of short-stay consumption to define the village’s future. Conversations about waste management, water use, and respectful behaviour are becoming more common, and they reflect a desire to keep the valley’s cultural and environmental resources intact. The dunes may be what draws many people here, but the long-term story will be written in how Hunder balances its role as a host with its need to remain, first and foremost, a home.

VIII. Bogdang: A Balti Village Holding Centuries of Stories

Language, Lineage, and Mountain Identity

Continuing down the valley, the road brings you to Bogdang, a Balti village where the texture of life feels both distinct and deeply rooted in the wider history of the region. Here, language is more than a means of communication; it is a living archive. The Balti spoken in courtyards and lanes carries echoes of histories that stretch toward Baltistan, now across a heavily managed border. Family lineages, too, map onto older patterns of movement that predate current geopolitical realities.

Spending time in Bogdang, you become aware of how identity is negotiated in layers: local, valley-wide, regional, and national. People speak of themselves as villagers, as part of Nubra Valley, as Balti, as Ladakhi, and as citizens of a larger republic, often in the same conversation. Religion, dress, and food all carry traces of these overlapping affiliations. The result is not confusion but a kind of mountain clarity: an understanding that life here has always been shaped by multiple horizons, from the nearby ridge to the distant routes once followed by traders and pilgrims.

Craft Traditions and the Echoes of Baltistan

Bogdang is also a place where craft and material culture quietly preserve links to Baltistan. Textiles, wooden architecture, and culinary practices all carry hints of that connection. While modern materials and designs are making their way into homes, older patterns and techniques are still remembered and, in some cases, actively maintained. You may notice carved doors, particular ways of arranging household items, or recipes that differ slightly from those in other parts of Nubra Valley.

In a world that often treats mountain communities as interchangeable backdrops, Bogdang stands as a reminder that specificity matters. The village’s crafts are not museum pieces; they are part of everyday life, adapted as needed but still anchored in a sense of continuity. For visitors willing to listen more than they speak, Bogdang offers a chance to understand how cultural memory can be carried not just in stories but also in the very objects people use and make, from cooking pots to doorframes.

IX. Turtuk: At the Edge of Borders and Histories

Apricot Orchards and the Architecture of Memory

Turtuk has, in recent years, acquired a reputation that far exceeds its size. Its apricot orchards, narrow lanes, and traditional houses draw visitors who are curious about a village that was, within living memory, on the other side of a contested border. Walking through Turtuk, you sense that architecture here is not only about shelter; it is about memory. Houses adapt to the slope, to the needs of extended families, and to a climate that demands both warmth and ventilation. Wooden balconies, ladders, and courtyards create a vertical choreography of daily life.

The apricot trees, heavy with fruit in season, have become part of the village’s contemporary image. But they are also linked to older patterns of subsistence and trade, when dried fruit travelled along routes that went much further than today’s tourist circuits. In the orchards, conversations move easily between the price of produce, the unpredictability of weather, and the presence of visitors wandering with cameras. Turtuk’s landscape, both built and cultivated, shows how a community can carry its history in the very ways it arranges stone, wood, and branches along the hillside.

How Turtuk Rejoined the World

Turtuk’s recent history involves a dramatic change of political status, shifting from one side of a border to another. For residents, this is not an abstract geopolitical fact; it is something that shaped family stories, educational paths, and economic possibilities. The village’s re-opening to visitors brought new attention, new income, and new questions about how much of its inner life should be placed on display. The sense of having “rejoined” a wider world is therefore complicated, reflecting both opportunity and vulnerability.

In Turtuk, you are always aware that the valley continues beyond what your permit allows you to see, and that people’s memories extend further than the maps in your guidebook.

Conversations with residents often touch on themes of belonging, dignity, and the desire to be seen as more than a curiosity at the edge of a border zone. The hospitality offered to visitors is genuine, but it also carries an unspoken request: to recognise the village as a place where history has been lived, not just watched from afar. In this sense, Turtuk is both an ending point on many itineraries and a beginning point for deeper reflection on what it means to travel through regions where lines on a map have cut across older, more fluid patterns of connection.

X. Reflections on the Road from Village to Village

Understanding Nubra as a Living Cultural Corridor

After days spent moving from Khardong to Turtuk, you begin to see Nubra Valley less as a collection of picturesque stops and more as a living cultural corridor. Each village—Khardong, Sumur, Kyagar, Panamik, Diskit, Hunder, Bogdang, and Turtuk—offers a distinct perspective on how people adapt to altitude, climate, and history. Yet they are bound together by shared rivers, shared festivals, and shared worries about the future. The valley functions like a long, inhabited bridge between worlds: between high passes and lower plains, between different languages and religious traditions, between memories of caravans and the current flow of visitors in rental cars and minibuses.

Understanding Nubra Valley in this way requires slowness. It asks you to pay attention not only to monasteries and statues, but also to irrigation channels, to the placement of shrines at crossroads, to the gestures with which tea is offered and accepted. It means noticing how school uniforms and traditional robes can appear in the same family photograph, how prayer flags share space with satellite dishes on rooftops, and how children move easily between local idioms and national curricula. The corridor is alive, constantly adjusting, but it is not directionless. It follows the rivers, the seasons, and the stubborn, hopeful desire to keep life going in a demanding but rewarding landscape.

The Value of Slowness in a Fast-Moving Travel World

In an era of accelerated travel, where itineraries are optimised for maximum coverage and minimal time, Nubra Valley quietly suggests another approach. The distances between Khardong, Sumur, Kyagar, Panamik, Diskit, Hunder, Bogdang, and Turtuk are not large in kilometres, but they are meaningful in experience. Each stretch of road offers a chance to notice how light changes on the cliffs, how the river braids or narrows, how the architecture of villages shifts slightly as you move downstream.

Choosing slowness here is not a romantic gesture; it is a practical way to respect a place where people do not live according to the logic of rush-hour traffic. Staying an extra night in a village, walking rather than driving short distances, and engaging in conversations that go beyond basic logistics all open up perspectives that no viewing platform can provide. In a fast-moving travel world, Nubra Valley rewards those who are willing to let their plans breathe a little, to accept that the most lasting impressions often come not from the highest viewpoints but from the quietest courtyards.

XI. Practical Notes (Subtle, Non-Guidebook in Tone)

Best Times for Cultural Travel Rather than Sightseeing

The question of when to visit Nubra Valley is often framed in terms of road conditions and weather, and those are, of course, crucial. Yet if your interest leans toward culture rather than box-ticking, you might think instead in terms of rhythm. Late spring and early autumn, when agricultural work is visible but not overwhelming, can offer a particularly rich sense of daily life. Fields are either being prepared or harvested, children are in school, and festivals dot the calendar without crowding it.

Summer brings longer days and more visitors, which can make it easier to find transport and accommodation, but it can also compress local life around the demands of hospitality. Winter, for those prepared for the cold and occasional disruptions, reveals a different Nubra Valley altogether: quieter, more introspective, yet still grounded in routines of care for animals, homes, and temples. Whichever season you choose, the key is to treat time not as a resource to minimise but as a medium through which understanding can thicken. Cultural travel here is less about perfect conditions and more about being present to the valley’s own pace.

How to Move Respectfully Through These Villages

Respectful travel in Nubra Valley begins with a simple recognition: these are not “remote attractions” but home villages for the people you meet. That recognition shapes everything that follows. Dressing modestly, asking before photographing people or their property, and keeping noise levels low at night are small but meaningful gestures. So is being attentive to local guidance about where to walk, especially around fields, shrines, and monastic spaces.

It also helps to remember that infrastructure here is both fragile and hard-won. Water, waste management, and road maintenance are constant challenges in a high-altitude desert. Choosing accommodations that take these realities seriously, carrying your waste out rather than leaving it behind, and supporting local businesses that invest in the community all make a difference. Above all, try to cultivate a posture of listening rather than collecting. The stories of Khardong, Sumur, Kyagar, Panamik, Diskit, Hunder, Bogdang, and Turtuk are not there to be consumed quickly; they are invitations into a longer conversation between people and place, one that will continue long after you have crossed back over the pass.

FAQ: Visiting the Villages of Nubra Valley

Is it possible to visit all these villages—Khardong, Sumur, Kyagar, Panamik, Diskit, Hunder, Bogdang, and Turtuk—in a short trip?

It is technically possible to pass through all of these villages in a few days, but doing so often turns Nubra Valley into a blur of names rather than a set of lived experiences. If your schedule is tight, consider choosing a smaller cluster of villages and spending more time in each, walking rather than driving where possible, and allowing room for unplanned conversations. The goal is not to collect locations, but to understand how life unfolds along the valley’s rivers and roads.

Do I need to prepare differently for Nubra Valley compared to other parts of Ladakh?

Nubra Valley shares many of the same high-altitude considerations as the rest of Ladakh—such as the need to acclimatise properly, stay hydrated, and respect the limits of your body. However, because you will be travelling through multiple communities, it is also worth thinking about how your choices affect local resources. Simple steps like carrying a reusable water bottle, minimising plastic use, and choosing homestays that prioritise sustainable practices can help reduce your impact while deepening your engagement with the valley’s cultures.

How can I learn more about local culture without intruding on people’s privacy?

One of the most respectful ways to learn about local culture is to participate in ordinary activities rather than demanding special access. Staying with families in homestays, shopping in village stores, and joining neighbours for tea when invited all create space for genuine exchange. Ask open-ended questions, listen more than you speak, and be willing to accept that some aspects of life here are not meant for visitors’ cameras or social media feeds. Often, the most meaningful insights come from small, unrecorded moments of shared time.

Conclusion: Carrying the Valley Home

As you drive back toward the pass, the villages of Nubra Valley recede in the rearview mirror but do not quite leave your thoughts. Khardong’s hillside homes, Sumur’s monastic stillness, Kyagar’s quiet histories of trade, Panamik’s steam, Diskit’s layered responsibilities, Hunder’s dunes, Bogdang’s Balti stories, and Turtuk’s orchards all continue to rearrange themselves in your memory, forming new patterns long after the journey has technically ended. Travel here does not offer simple lessons or easily packaged revelations. Instead, it leaves you with a set of questions about how people build and sustain life in places where climate, politics, and globalisation all intersect.

Carrying the valley home means more than saving photographs or marking locations on a map. It involves letting the patience, resilience, and understated generosity you encountered in Nubra Valley influence how you move through your own daily environment. The quiet roads between its villages remind you that the most enduring journeys are not those that chase the spectacular at every turn, but those that allow you to see how ordinary life—tending fields, teaching children, repairing walls—can be as extraordinary as any summit view, when given enough attention and respect.

Closing Note: Letting the Road Change Your Pace

If there is one gift that the road from Khardong to Turtuk offers, it is a recalibration of pace. The valley does not hurry for you, and that is precisely its kindness. Traffic pauses for herds, weather reshuffles plans, and conversations run on longer than expected over cups of butter tea. In accepting this slower tempo, you may find that something in your own internal timetable loosens as well.

When you finally return to busier streets and denser calendars, the memory of Nubra Valley can act as a quiet counterpoint—a reminder that there are still places where mountains, rivers, and villages insist on being met on their own terms. Let that memory guide you toward choices, in travel and at home, that leave more room for listening, for patience, and for the kind of attention that turns a simple road into a lifelong reference point.

About the Author

Declan P. O’Connor is the narrative voice behind Life on the Planet Ladakh,

a storytelling collective dedicated to exploring the silence, culture,

and resilience of Himalayan life through carefully observed journeys and

quietly attentive essays.